Against the Current, No. 202, September/October 2019

-

Hope Is in the Streets

— The Editors -

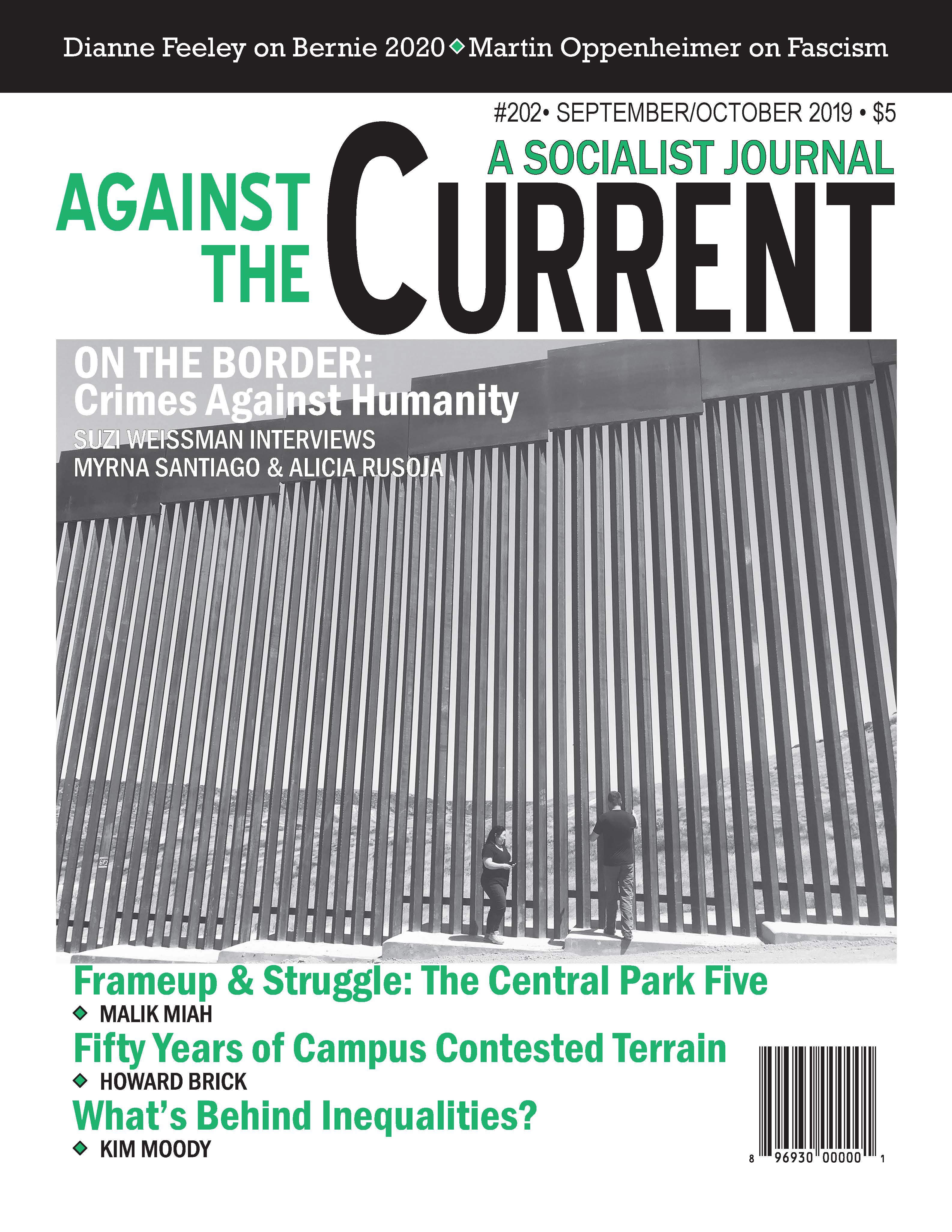

Talking to Those on the Border

— Suzi Weissman interviews Myrna Santiago & Alicia Rusoja -

What the Sanders' Campaign Opens

— Dianne Feeley -

Making the Master Race Great Again

— Steven Carr -

The Central Park Five Frameup

— Malik Miah -

Algerian Feminists Organize

— Margaux Wartelle interviews Wissem Zizi -

Palestine: Imperative for Action

— Bill V. Mullen -

The Crisis of British Politics

— Suzi Weissman interviews Daniel Finn - Siwatu Salama-Ra Conviction Overturned

-

Contested Terrains on Campus

— Howard Brick - Reviews

-

Competition, Inequality & Class Struggle

— Kim Moody -

Learning Through Struggle

— Marian Swerdlow -

What Is Working-Class Literature?

— Matthew Beeber -

A Debate That Never Ends

— Steve Downs -

Fascism--What Is It Anyway?

— Martin Oppenheimer -

Bolivia's Legacy of Resistance

— Marc Becker -

China: From Peasants to Workers

— Promise Li - In Memoriam

-

In Memoriam: James Cockcroft, 1935-2019

— Patrick M. Quinn

Marc Becker

The Five Hundred Year Rebellion:

Indigenous movements and the decolonization of history in Bolivia

By Benjamin Dangl

Chico, CA: AK Press, 2019, 220 pages, $18 paper.

BOLIVIA HAS LONG been one of the most politicized countries in Latin America, perhaps rivaled only by Cuba, with a population intimately aware of its role in a global capitalist environment. Furthermore its inhabitants are able to critique that situation and willing to act against it.

That understanding emerges out of a long history of extractive economies. Cuba was Spain’s initial and most long-lasting foothold in the Americas. The island’s economy boomed with the collapse of sugar production in neighboring Saint Domingue in the aftermath of Haiti’s slave revolt, which led to United States domination of the Caribbean during the first half of the 20th century.

Similarly in Bolivia, discovery of silver at Potosí in the 16th century introduced a long period of brutal colonial exploitation that likewise underdeveloped its economy.

In 1952, Bolivian reformers organized in the Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario (MNR, Revolutionary Nationalist Movement) led a successful military coup that quickly radicalized into a program that nationalized the tin mines and transformed an archaic landholding system with the distribution of land to farm workers.

Those social programs influenced the Cuban revolutionaries and the program they implemented when they marched into Havana seven years later. With these parallel histories, it is probably no coincidence that the two countries share similar militant traditions of critiquing colonial and capitalist exploitative enterprises.

Journalist, researcher and activist Benjamin Dangl’s new book on Indigenous movements in Bolivia from 1970 to 2000 builds on and contributes to this history. His book draws on the work of other scholars, archival research, his own firsthand experiences and observations of the dramatic political and social changes in recent decades in Bolivia, and in particular interviews with social movement activists.

He argues that grassroots mobilizations drew on memories of the past to agitate for social change, to develop new political projects, and to propose alternative models of governance. This book is particularly strong in its analysis of political uses of history.

Thirty Years of Organizing

Dangl frames his study with the 2015 inauguration of Bolivian president Evo Morales for his third term in office, but does not discuss current politics in any depth. He points to other works on the subject, including that of political scientist Jeffery Webber, From Rebellion to Reform in Bolivia: Class Struggle, Indigenous Liberation, and the Politics of Evo Morales (Haymarket Books, 2011) and Dangl’s own previous writings, especially The Price of Fire: Resource Wars and Social Movements in Bolivia (AK Press, 2007) and Dancing with Dynamite: States and Social Movements in Latin America (AK Press, 2010).

This new book provides important and useful historical context for this “dance” between electoral politics and social movement organizing strategies that he and others have examined. Dangl scrutinizes a sequence of organizations in a 30-year sweep of social movement organizing in Bolivia that largely predates the emergence of Morales as an elected leader.

Some readers may find the reference to the “Five Hundred Year Rebellion” in the book’s title a bit disorienting. Rather than examining this long history of resistance itself, Dangl looks at how social movements in the last third of the 20th century made political use of these historical narratives to shape and advance their own contemporary struggles. For an accessible overview of that longer history, Forrest Hylton and Sinclair Thomson’s Revolutionary Horizons: Popular struggle in Bolivia (Verso, 2007) provides a fluid and compelling narrative.

Dangl begins his discussion of historical production and analyses with the Kataristas, a movement that took its name from Tupac Katari who led a bloody anti-colonial revolt in 1781 that ended with his execution. Katari proclaimed that he would return and would be “millions,” a prophecy that his successors claimed to have come true with these contemporary social movements.

The Kataristas broke from the paternalistic tendencies of the MNR that led the 1952 revolution, proclaiming that they were no longer the peasants of 1952. The Confederacio?n Sindical U?nica de Trabajadores Campesinos de Bolivia (CSUTCB, Unified Syndical Confederation of Rural Workers of Bolivia) built on this tendency to mold a historical consciousness as a tool in organizing rural populations.

Their efforts shaped a political project that strongly informed subsequent peasant and Indigenous movements. One of these most significant organizations was the Consejo Nacional de Ayllus y Markas de Qullasuyo (CONAMAQ, National Council of Ayllus and Markas of Qullasuyu), which in particular sought to reconstruct traditional community structures called ayllus.

These groups created a collective vision for the transformation of Bolivian politics and society. Dangl argues that the intellectual production of these grassroots organizations was essential for mobilizing and empowering social movements.

Popular appeals to a history of oppression and resistance helped grow a movement, and offered strategies and symbols for advancing their political agenda. This intellectual production was in particular the project of the Taller de Historia Oral Andina (THOA, Andean Oral History Workshop) that sought to recover Indigenous histories that the ruling class had written out of the educational literature.

Sociologist Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, who taught at the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés in La Paz, organized a project alongside other THOA members of gathering interviews and drafting collective histories of rural communities. Dangl explores in detail one particular example of early 20th-century leader Santos Marka T’ula, who subsequently became revered for his contributions to grassroots struggles.

The Kataristas who launched this sequence of grassroots mobilizations in the 1970s famously declared they would critique society with “two eyes,” as both Indians and peasants or, if you will, through the lens of both class and race. As Katarista militants developed this critique of colonialism, however, the “eye” of class became displaced with a primary emphasis on race or ethnicity.

Class and Race Contradictions

Although Bolivian universities had a strong and highly developed tradition of Marxist class analysis, Rivera and others who encouraged this tendency of anti-colonial thought emphasized ethnic identities and marginalized leftist critiques. An unfortunate consequence of this ethnic turn is a type of reactionary Aymara fundamentalism that essentializes ethnic identities at the cost of downgrading class struggles.

Historian Waskar Ari presents a more extreme example of this in his book Earth Politics: Religion, Decolonization, and Bolivia’s Indigenous Intellectuals (Duke University Press, 2014), which similarly examines how Aymara nationalists invented a discourse of decolonization that — in looking backward to embrace religious traditions — rejected leftist critiques of political economies.

I would argue — although Dangl might not agree — that a better and ultimately more successful approach would be to follow the lead of Marxist critiques of intersectionality to understand how race, class, gender and other forms of oppression exist on fundamentally different planes and require different types of resistance that do not necessarily intersect but require distinctive and more complex analyses to advance grassroots struggles.

Privileging ethnic identities over class struggles undermines a more complete analysis of societal structures, and a fuller analysis of these issues is important to understand the relative strengths and weaknesses of grassroots social movements.

Political movements are often comprised of multiple and conflictive ideological tendencies, and Bolivia is no exception in this regard. All the contradictions of a decolonial struggle are readily apparent in Morales’ government. Benjamin Dangl contributes an important study that helps us understand how we arrived at this point, and provides food for thought as to how we can proceed forward to a more just and equal world.

September-October 2019, ATC 202