Against the Current, No. 202, September/October 2019

-

Hope Is in the Streets

— The Editors -

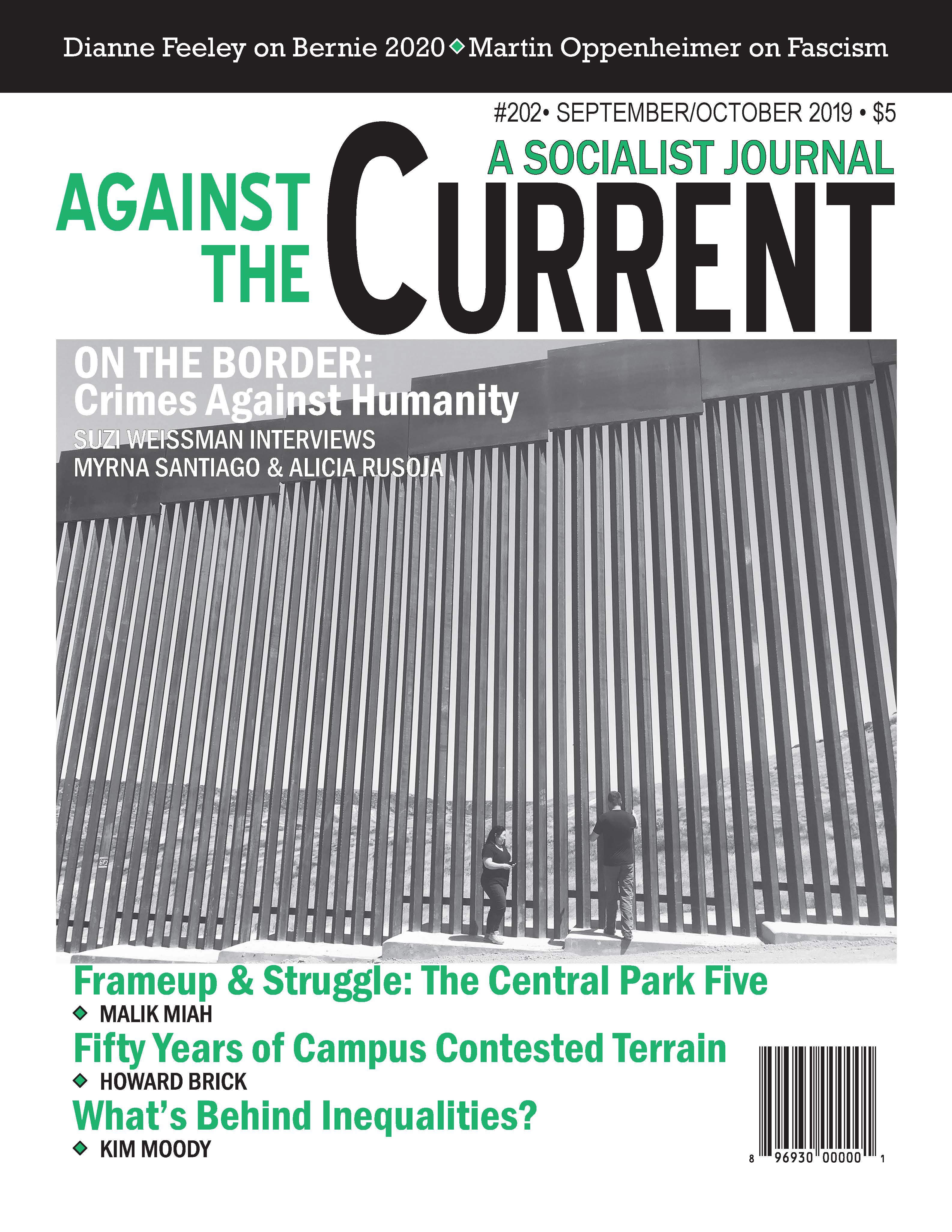

Talking to Those on the Border

— Suzi Weissman interviews Myrna Santiago & Alicia Rusoja -

What the Sanders' Campaign Opens

— Dianne Feeley -

Making the Master Race Great Again

— Steven Carr -

The Central Park Five Frameup

— Malik Miah -

Algerian Feminists Organize

— Margaux Wartelle interviews Wissem Zizi -

Palestine: Imperative for Action

— Bill V. Mullen -

The Crisis of British Politics

— Suzi Weissman interviews Daniel Finn - Siwatu Salama-Ra Conviction Overturned

-

Contested Terrains on Campus

— Howard Brick - Reviews

-

Competition, Inequality & Class Struggle

— Kim Moody -

Learning Through Struggle

— Marian Swerdlow -

What Is Working-Class Literature?

— Matthew Beeber -

A Debate That Never Ends

— Steve Downs -

Fascism--What Is It Anyway?

— Martin Oppenheimer -

Bolivia's Legacy of Resistance

— Marc Becker -

China: From Peasants to Workers

— Promise Li - In Memoriam

-

In Memoriam: James Cockcroft, 1935-2019

— Patrick M. Quinn

Marian Swerdlow

Red State Revolt:

The Teachers’ Strike Wave and Working-Class Politics

By Eric Blanc

Verso, 2019, 224 pages, $19.95 paper.

THE TEACHER STRIKES that swept through “Red States” in early 2018 demonstrated how suddenly powerful upsurges can arise within the working class. The fire was lit in West Virginia and spread through half a dozen such states, surprising observers because the social conservatism of these states’ populations seemed at odds with the politics of the rising.

These educators challenged sacred cows of social conservatism such as cheap small government, and the privatization and discrediting of public education, and they did so often with the widespread support of their communities. Their rising breached and weakened the austerity regimes in their states, and drowned out the narrative that educators are to blame for the weaknesses of public education.

Eric Blanc has written an intelligent, often insightful, and vivid account of this momentous movement, Red State Revolt. In the first of his three chapters, “The Roots of Revolt,” Blanc observes that it “erupted in a period of virtually uninterrupted working class defeats and neoliberal austerity.” However, “the walkouts were not an automatic response by Red State teachers to receiving the country’s worst salaries.” He credits neither spontaneity nor any “worse the better” theory.

Blanc writes about what he considers the three most important strikes — West Virginia, Arizona and Oklahoma. He shows that the latter had a much less favorable outcome than the other two. According to Blanc, many common factors led to all three uprisings, and all faced similar challenges.

In his final and lengthiest chapter, “The Militant Minority,” Blanc explores the reasons for these differences. He makes a convincing case that the different outcomes were due to “the existence of a ‘militant minority’ of workplace activists” who played a leadership role in West Virginia and Arizona, but were absent in Oklahoma.

The clearest and strongest part of Blanc’s concept of what distinguishes the “militant minority” from other activists is their shared political perspective, including being union members yet willing to act independently, if necessary, against the top union officialdom. Less convincing is when he distinguishes them by their level of experience, which is often limited to a couple of years of activism, or less.

But Blanc makes clear that all had learned — perhaps as much from studying and paying attention to many struggles, as from personal involvement — about unions, how to organize workers, and how to bring about change. Most thought deeply about these questions. He points out that during the mass working-class upsurges in U.S. history, it was Communists, socialists and Trotskyists who played this role, but that one doesn’t have to be any of those to be part of a militant minority.

Leadership Matters

In the first state to rise, West Virginia, Blanc views the main contribution of the militant minority as winning the state’s teachers to the idea of a strike. Two rank-and-file leaders, Jay O’Neal and Emily Comer, both members of the state teachers’ union, started a Facebook page in response to yet another state initiative to make its employees’ health insurance, the PEIA, less comprehensive and more expensive.

Although the two moderated the page, they allowed all page members to post on it. Not only did they argue for a strike, they brought forward the idea that the “fix” for the health insurance system should be more progressive taxation.

Blanc contrasts Oklahoma, the next of the three states to rise, with both of the others for its absence of a militant minority. In that state, there were two competing rank-and-file initiatives based on Facebook pages. Neither page founder was a union member, and neither raised demands around progressive taxation. On the more popular page, only the founder could make posts. Other members were limited to comments or responses to polls.

Another weakness in Oklahoma was that both the rank-and-file leaders and the state union, the Oklahoma Educators Association (OEA) adopted a strategy reliant on the support of local Superintendents. Neither rank-and-file leader advocated a strike vote among school employees, or coordination of the strike with the OEA. Instead they asked teachers to reach out to Superintendents and work with them directly.

This made striking less risky, but it also put a great deal of control over the strike in middle management’s hands. Finally, neither leader saw any need to organize on the school level.

Hoping to avert a strike set for April 2, the Oklahoma legislature passed a bill giving teachers a raise of roughly $6,000 or 15%. But it included only minimal funding for schools and a modest raise for school support staff.

Despite all this, Blanc notes that the walkout was “massive, given Oklahoma’s weak labor organizations and traditions.” He concludes that the relative failure of the strike there cannot be attributed to lower levels of educator militancy or mobilization.

After April 2, the Superintendents, satisfied with the 15% raise in the new state legislation, began pulling back their support for the strike. Although educators remained off the job and in the capital for 10 more days, desperately hoping to increase school funding, the legislature refused to budge. “The limitations of an infrastructure based purely on Facebook became glaring,” Blanc observes, “in the absence of clear leadership or an organized effort from below . . . the crowd began to decline.”

On April 12, the OEA officials abruptly pulled the plug on the walkout. “Teachers across Oklahoma were outraged at OEA leaders. Hundreds dropped their dues.” Instead of the strike building the union, as it did in West Virginia and Arizona, the strike eroded it. Blanc concludes that this is an object lesson of what can happen without leadership by experienced rank-and-file organizers connected to unions.

Victory Againt the Odds

Turning to the last state to rise, Blanc observes that Arizona, “inhospitable to labor and the left” is the “perfect test case for the importance of a radical militant minority.” It is better to compare Arizona with Oklahoma than with West Virginia because of the latter’s “relatively strong labor movement and traditions.”

The militant minority there was a core of about 10 activists who came together through a Facebook page, Arizona Educators Union (AEU). One, Rebecca Garelli, was a veteran of the 2012 Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) strike. She was an invaluable living textbook of its lessons. She proposed building a structure of workplace representatives, as the CTU had done.

Blanc comments that these liaisons were “the most important part of the movement.” Furthermore, AEU’s two-month organizing campaign was done hand-in-hand with the Arizona Educators Association (AEA), the state teachers’ union.

Again, Garelli drew on her Chicago experience to coordinate escalating actions to build educator confidence and unity, as well as community support. By late March, the AEU invited its members to collectively draw up demands online and in the workplace. The final demands were presented at a mass rally in the capital on March 28.

“After two months of deep organizing,” says Blanc, the AEU had “won over school employees of all persuasions.” Although most AEU leaders were initially skeptical of striking in Arizona’s right-wing, anti-labor political landscape, after 110,000 Arizonians participated in walk-ins on April 11, they decided to hold a strike authorization vote.

As the strike began on Thursday, April 26, and Friday, April 27, the governor announced he had reached a deal with the legislature for a 20% raise without cutting services.

The AEU leadership polled its liaisons and found they and their colleagues still wanted to return to the capital and continue the strike on Monday. But on Tuesday afternoon, the AEU and AEA made a joint announcement of a return to work on Thursday if the governor’s bill passed.

Blanc reports that “a majority of teachers were upset that [the leaders] did not give them a choice . . . momentum declined rapidly . . . it seemed as if Arizona’s walkout denouement might end looking more like the implosion in Oklahoma.”

Although this seems like a very serious, and potentially devastating, error on the part of AEU leaders, Blanc merely observes, “After the fact, AEU representatives agreed that it had been a mistake not to put the question up for a vote.”

What saved the strike from failure was the initiative of a single member of the AEU leadership team, Dylan Wegela, who had been the most consistent advocate of militant action from the start. He thought of a way the strike could be revitalized by fighting to add amendments to the governor’s bill that would embody more of the strikers’ demands, including better ratios of teachers and counselors to students, and raises for other school staff besides teachers.

While the Republican legislature voted all the amendments down, morale among the strikers rebounded, and the strike ended with a fight rather than dissipating in an anticlimactic letdown.

Contrasting Results

Blanc very effectively contrasts the results of the three strikes. In the West Virginia strike, educators forced politicians to back down from proposed changes in public employee health insurance charges, and to give an across-the-board 5% raise to all state employees, and more than 2,000 educators joined unions.

In Arizona, strikers forced a 20% raise that was not funded by cutting social services, and a scrapping of bills for a referendum on school vouchers, for tax cuts, and for tax credits by the Republican State Legislature.

Approximately 2,500 new members joined the AEA during that spring. In contrast, Oklahoma educators won nothing during their walkout to add to the raise they’d gotten by their strike threat; Blanc reports that the OEA actually lost hundreds of members. After extensive and detailed discussion, Blanc concludes convincingly, “What was missing in Oklahoma was a team of like-minded grassroots militants, armed with activist knowhow . . . and an orientation toward working within unions to push them along.”

In the book’s middle chapter, “The Power of Strikes,” Blanc thoroughly discusses how strike leaders built — or, in the case of Oklahoma, failed to adequately build — unity. He points out that unity is built through “deeds, not words.”

In West Virginia, rank-and-file and union leaders organized “wear red” days, a rally at the state capital and school site strike votes by all school employees in all titles, union and non-union.

How to Build Unity?

Even in such a politically and racially homogenous state, divergent political perspectives were a source of division. Rank-and-file leaders in West Virginia and Arizona consciously pushed for demands that would unite all school employees, not only teachers, which made the movements there bigger and more powerful. Militant minority leaders were the ones who understood why and how to build unity.

They also limited their list of demands. Blanc comments, “Had educators attempted to make broad ideological agreement or a long list of demands a precondition for unity in action, their movements would have never gotten off the ground. Instead, they focused on the big, burning demands that the vast majority of school employees and community members already felt strongly about.”

He reports finding this orientation among members of the rank-and-file themselves. For example, when he asked strikers about the particular challenges facing female teachers, “they almost always responded by pivoting . . . insisting the movement united all educators.”

This raises a question that Blanc treats less successfully: the racial implications, for both strikers and their community supporters, of a unity based on limited demands. Blanc observes that “the unconscious prejudices of white workers did not prevent them from striking with their non-white co-workers for common demands.” This does not seem noteworthy.

White workers refusing to participate in a strike because non-white members of their union were striking has not been a problem in teacher strikes, public employee strikes, or in any U.S. strikes during at least the last 40 years. The threat to interracial unity among strikers is usually that the white workers reject the demands raised by people of color to address their special oppression, and that rejection weakens those workers’ support. Blanc himself gives an example of this during the Red State uprisings, when white teachers in Kentucky rejected Black teachers’ demands against an impending racist “gang” bill.

Although Blanc does not give statistics for the racial composition of the teachers in the states he discusses, he does say that “a majority of the strikers were white,” and that Oklahoma had an “overwhelmingly white teaching force.” Since West Virginia’s overall population is 92% non-Hispanic white, it is likely its strikers, too, were overwhelmingly white.

Race has also played an important role in public reaction to teacher strikes. Historically, teacher strikes were mainly urban, and provoked hostility in Black communities, who saw them as yet another way their children were being educationally shortchanged, and yet more evidence that predominantly white teachers did not care about their children.

In 2012, the CTU’s signal accomplishment was to turn that around by making their contract campaign and, finally, their strike, into a fight against what it denounced as “educational apartheid,” as well as for better job security and working conditions for school workers.

The Red State strikers all demanded more school funding. Demands on behalf of students were especially prominent in Oklahoma, where they were second only to wage demands. Educators in West Virginia and Arizona did grassroots organizing for months before the strike, talking to parents, holding walk-ins with parents, passing out educational flyers, and waving signs.

As one might expect from Blanc’s discussion of the basis for strikers’ unity, none made any special demands for students of color. Blanc argues that the “race blind” demand for more school funds was “objectively anti-racist.”

He also claims that because of the strikes, “thousands of conservative educators began to question their Republican affinities,” and that this amounts to “a redirection of popular anger upward, against the ruling rich,” and that this, too, has “profound anti-racist implications.” However, even if we accept the reasoning that disillusionment with Republican politicians equaled “anger toward the ruling rich,” this is still the same kind of “color blind” stance that flawed even the greatest Socialist Party leaders as long as a century ago.

It may have been easy to sidestep racial inequality in West Virginia, where 92% of the population is non-Hispanic white, or even in Oklahoma, where the non-white population is divided into 8% Black, 11% Hispanic and 9% Native American. But in Arizona, 70% of public school students are Hispanic, as is 32% of the population.

Interestingly, community support for the strike does not seem to have been as strong in Arizona as in West Virginia or Oklahoma. (For example, Blanc quotes Garelli explaining why the AEU decided to end the strike without a vote: “A lot of parents may not have responded well if we continued the walkout.” In the other two strikes, there’s no mention of any similar concern.)

Blanc passes over this, but one reason may have been the strikers’ failure to raise issues affecting Hispanic students specifically. Another dynamic of earlier urban teacher strikes, which John Shelton documents in his book Teacher Strike! (2017), was the hostility they generated among whites who resented paying higher taxes to fund education for urban students of color. This factor, too, may have been at play in Arizona.

“The Union Paradox”

An aspect of the revolts that Blanc covers well is what could be termed “the union paradox.” On the one hand, weak union allowed space for militancy; on the other, the resources of even such weak unions were necessary for the success of the Red State strikes.

Blanc observes that, “since unions were weak and collective bargaining nonexistent, the strikes took on an unusually volcanic and unruly form,” which made them especially disruptive and exacerbated the social and political crisis they precipitated. He likens the teachers’ lack of full collective bargaining rights to “a pressure cooker with no escape valve.”

Blanc explicitly denies that workers are more powerful without unions: “ . . . there’s no strategic substitute for a strong trade union movement.” Yet, in West Virginia, “it was only under growing pressure from below” that top union officials began to shift toward favoring a work stoppage.

Blanc observes that an important factor contributing to the effectiveness of this pressure was that since West Virginia was a “right-to-work” state, workers could stop paying dues at any time. “Although weakening the trade union movement as a whole, [this situation] creates a qualitatively different power relations between union ranks and officials.” Still, he adds hastily, right-to-work laws “are an impediment to sustaining working class power.” (Since the Janus decision, this situation now obtains throughout all U.S. public employee unions: time will tell if this different power relation leads to greater militancy.)

Blanc reports that “the most empowering moment of the strike [in West Virginia] was the night it went wildcat . . . West Virginia Education Association (WVEA) President Dale Lee announced to the massive crowd that the strike was over . . . educators began chanting . . . ‘Fix It Now,’ ‘Back to the Table,’ ‘We are the bosses.’” Blanc comments, “The wildcat saved the strike.”

On the other hand, in all three states, Blanc documents that the strikes could not have achieved what they did without the resources the official unions provided, such as office staff, research teams, tactical advice, and even financial help.

In West Virginia, when the size of the movement grew so much it exceeded the organizational capacity of its rank-and-file leaders, the official union stepped in to lead. (With 70% of West Virginia teachers union members, the WVEA was in a far stronger position than the unions in Oklahoma — 40% membership — or Arizona — 25% membership.) Still, as observed above, when it tried to settle for an inadequate deal, the rank and file itself took leadership into its own hands.

A related paradox Blanc explores is how the fact that unions’ political “allies,” the Democrats, were out of power in the Red States actually contributed to stronger and more effective union action. Unions were less hesitant to strike against Republicans: “the fact that Republicans were in power created considerably more room for maneuver.” In blue states, teacher unions are more reluctant to strike, since a strike is an attack on their allies, the Democratic Party, paradoxically leading them to eschew labor’s most powerful weapon.

How Social Media Helps and Hinders

Blanc discusses the role of social media in building mass militancy with insight and nuance. He observes that “without social media, there is no chance that the Red State Revolt would have developed as it did.” Yet when West Virginia rank-and-file leaders set up a Facebook group in response to the proposed changes in PEIA, few people joined until the organizers took clipboards and sign up sheets to PEIA informational meetings.

Another problem of social media Blanc finds is that it can “scale up too fast,” and outpace political relationships and infrastructure, and challenge internal democracy. Blanc concludes, “Real workplace power can’t be forged solely through Facebook.”

Developing a Winning Strategy

Blanc claims that during the uprisings, “the importance of trade unions . . . became widely evident.”

Interestingly enough, although the unions in Arizona and West Virginia grew in absolute numbers, at no time did strikers in any of these states raise demands for greater rights for unions. Although public employee strikes are illegal in all three states, not even the militant minority leaders, as far as Blanc reports, even considered raising the demand to make strikes legal.

In Arizona, where there is no legal right to collective bargaining for teachers [Sanes, Milla and John Schmitt, “Regulation of Public Sector Collective Bargaining in the States,” The Center for Economic and Policy Research, March, 2014] the AEU, as far as Blanc reports, never considered a demand for that right. There is some indication that the AEU succeeded in organizing teachers in that intensely anti-labor state, precisely because they were not a union. One of its leaders is quoted saying “the Arizona Education Association . . . didn’t have the . . . trust of our members. There’s strong anti-union sentiment in Arizona . . . It was important for AEU not to have partisan affiliation,” with a strong suggestion that “partisan” here means “union.”

This is in marked contrast to the teacher strikes of the 1960s to early 1980s documented by Shelton, which almost invariably demanded, and usually won, exclusive union recognition and the right to collective bargaining, and even, occasionally, the legal right to strike.

Blanc emphasizes the importance of the role of strikes in revitalizing the labor movement, pointing out the failure of other strategies, and the role strikes have played in U.S. history in creating a powerful labor movement that forced both capitalists and the bourgeois state to make important concession to the working class.

However, when Blanc claims that the Red State strikes “radically transformed the collective organization, self-confidence and political consciousness of working people,” he seems on less solid ground.

Certainly, during the uprisings, strikers felt confidence, unity and empowerment. However, it is yet to be seen whether these changes are lasting or temporary. We don’t know whether, for example, the liaison network AEU created will endure.

Unions in Arizona and West Virginia grew. But since Blanc gives prior union density in percentages, and the size of growth in absolute numbers, it is difficult to judge whether this growth was a “radical transformation” of those unions.

To illustrate changes in political consciousness, Blanc mentions educators’ realization of “the extent of the subordination of politicians and governmental policy to big business,” and “disillusionment with Republican Party politicians.”

As important as these changes in consciousness are, it’s not clear they are “radical transformations,” or merely bring the Red State teachers into line with large numbers of others in “blue states.” Hopefully, the Red State revolts will be part of the beginning of such a radical transformation, by the inspiration of their example and their success.

So as significant as the changes brought about by the Red State risings are in the context of the overall continuing retreat of the U.S. working class, and the extremely conservative nature of those states in particular, it seems more accurate that these strikes show the potential for working-class collective action, rather than a “radical transformation of . . . the level of working class collective organization.”

Blanc is optimistic that, as a result of the uprising, “a small but not insignificant number of strikers concluded that systematic solutions will be needed to resolve society’s underlying crisis of priorities.” However, he does not discuss what “systematic solutions” meant to these strikers, or whether they had developed any ideas as to the reasons why this society has the priorities that it does.

Blanc himself can be fuzzy on his own thinking on these matters. For example, he speaks of “the immense potential for working class politics,” but leaves unanswered the questions, “potential for what? To do what?” He says “the left needs labor [in order] to win,” but doesn’t address the question, “Win what?” He speaks vaguely of “a better world,” and of socialists’ “inspiring vision of a better future.” He speaks of “the system” that “depends upon our labor,” but does not name the system.

Related to this is Blanc’s use of terms from revolutionary Marxism while changing their meanings so that their power to propel us from fighting for important reforms to organizing for revolutionary change is weakened. For example, he uses “class struggle unionism” as a synonym for militancy.

However, the term, in the part of the revolutionary left that developed it, conceptualized a far more dynamic, proto-revolutionary consciousness and practice that would be a transition from militancy to revolutionary Marxism [See, for example, Jack Weinberg, “Class Struggle Unionism,” Sun Press: 1975].

In a similar vein, Blanc refers to “the importance of trade unions and worker solidarity . . . the potency of the strike weapon” as “lessons in class consciousness.” While class consciousness includes these elements of trade union consciousness, what makes it a far more potent force for change is that it encompasses the realization that all workers, of all nations and races, and regardless of legal status, are part of the same class and share the same long-term interests.

Eric Blanc argues that the left needs a strong and militant labor movement in order to achieve its goals. But he warns that “it is not inevitable that the growth of socialist organizations will result in the rebirth of a militant labor movement.”

The problem, as he sees it, is that “most young activists today are not convinced of the centrality of workplace organizing.” Blanc is clearly convinced of this centrality, and would like to see socialists take jobs where they could do workplace organizing, although he cautions that “the presence of experienced radicals in an industry doesn’t automatically enable collective militancy. Conditions need to be ripe.” If Red State Revolt can win more of these young activists to this idea, it will have significant political importance.

September-October 2019, ATC 202