Against the Current, No. 100, September/October 2002

-

Whole New Worlds of Turmoil

— The Editors -

Longshore Battle: Bush, Butt Out!

— Dianne Feeley -

Anger at the International AIDS Conference

— Sam Friedman -

Race and Class: Cops and Videotapes

— Malik Miah -

The Rebel Girl: "Normal" Domestic Violence?

— Catherine Sameh -

Radical Rhythms: Music to Rock Your World

— Kim D. Hunter -

Zionism, Non-Jews and the Israeli State

— Ur Shlonsky -

Palestinian Elections Now

— Edward Said -

After 9/11: Empire Uncaged

— Michael Ames Connor interviews Rahul Mahajan -

Against the Current Celebrates 100 Issues

— Christopher Phelps -

Europe's Specter of Americanization

— Peter Drucker -

An Economy of Two, Three Many Enrons

— Robert Brenner -

"Love for Sale," A Sex Trade Exhibition

— Dianne Feeley -

Random Shots: Life Imitates Art

— R.F. Kampfer - Immigrant Trials and Triumphs

-

From Immigrants to Labor Troublemakers

— Teófilo Reyes -

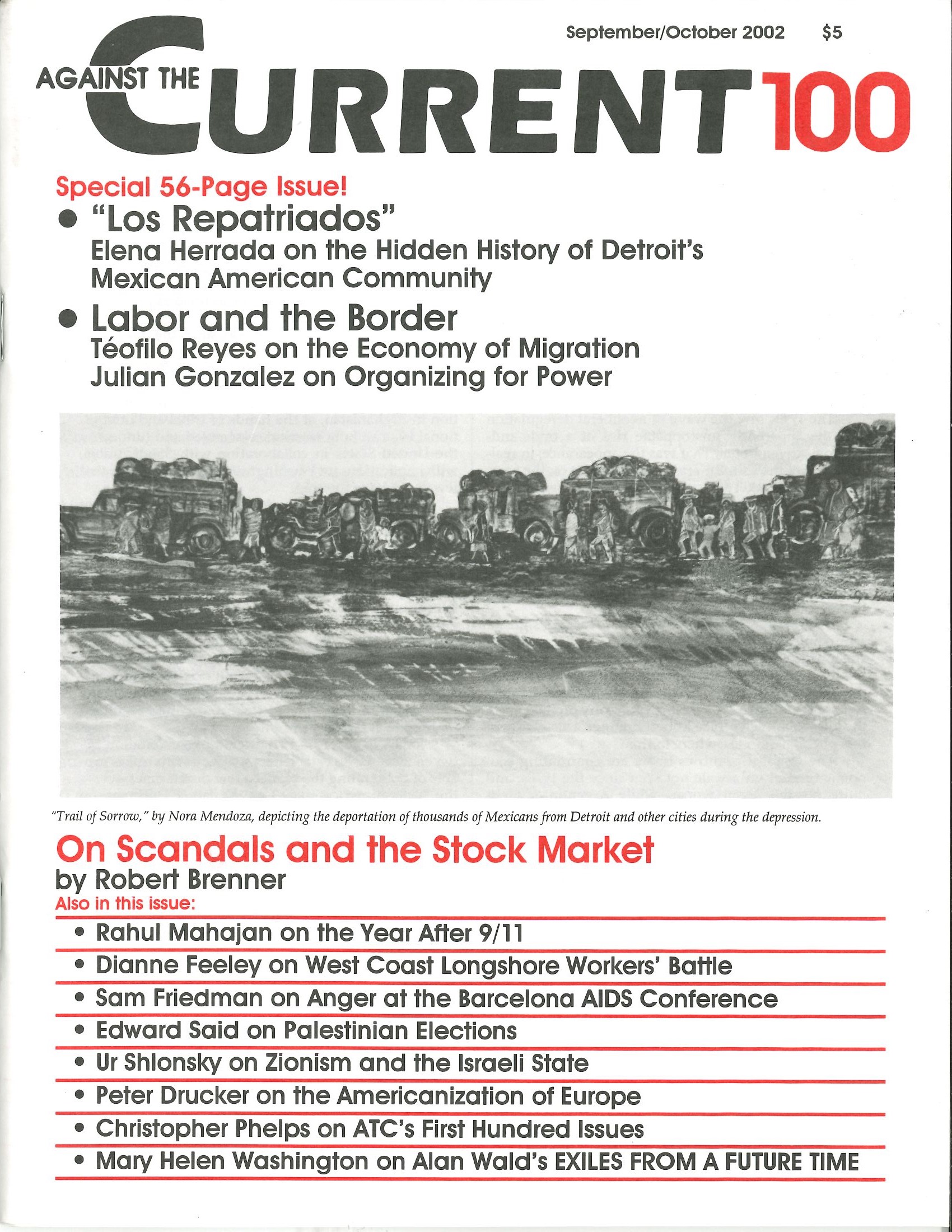

The Hidden Story of "Los Repatriados"

— Elena Herrada -

Arab Detroit: from Margin to Mainstream

— review by Brian Smith -

Arab Americans in Metro Detroit

— David Finkel - Reviews

-

Lives of the Exiles

— Mary Helen Washington -

A Book of Lamentations

— David Finkel -

How Many Modernisms?

— Alan Filreis - In Memoriam

-

Trim Bissell, A Committed Life

— Chuck Kaufman -

June Jordan and the Language of Your Life

— Ellen S. Jaffe

David Finkel

Arab Americans in Metro Detroit

A Pictorial History

by Anan Ameri and Yvonne Lockwood

(Chicago: Arcadia Publishing, 2001) 128 pages

$19.99 (paperback).

THE PICTURES AT a superficial glance may look like standard-issue family memorabilia — until you learn the astonishing stories behind some of them.

“Cash For Your House. The City will pay a good fair price for any house in this block. See City Attorney. City Hall,” reads a nondescript sign on a lot in the South End of Dearborn, 1971. You can’t understand what it means unless you hear the Arab American residents explain.

Dearborn Mayor Orville Hubbard, one of the most extreme racists this side of Lester Maddox, wanting to replace the immigrant working-class population with an industrial zone, had the city council pass a zoning ordinance prohibiting any home improvements in the neighborhood close to the Ford Rouge plant.

People were then “encouraged” to sell their homes, at grossly depressed rates since the buildings were not (and could not be brought) “up to code.”

This tactic is more than vaguely reminiscent of Israeli policies in East Jerusalem. In America, however, the Arab homeowners had some legal rights and used them fiercely — mobilizing a civil rights battle that wound its way through the courts for almost two decades, until the city finally conceded.

As Arab Americans in Metro Detroit explains, the primarily Syrian and Lebanese residents who fought that battle have mostly moved on, leaving the neighborhood today mostly to more recent immigrants from Yemen and Iraq. (81)

Another photograph shows a newly married couple in formal pose, with the explanation: “After a nine-year engagement, Dib and Sara Abdalla were married in 1922. Dib joined his uncle in Detroit in 1912 . . . Dib Abdalla worked for ten years, sending money to his parents and his fiance’s family before returning to his village in Syria to marry Sara.” (128)

But again, you have to hear Marie Abdalla tell the story of what her parents went through afterward.

Travelling back to the United States via Marseille, France, Sara Abdalla failed an eye exam and had to remain for several months in France, where she had her first daughter Rose, while Dib returned to the United States to work.

Arriving at Ellis Island, Sara again failed the eye exam and was held with her daughter in a hospital on the island. After five months Dib, who was billed $4.25 per day for his wife and child, sent a letter asking why he was being billed for Rose since she was nursing and sleeping in her mother’s bed.

Without responding to Dib Abdalla’s letter, the hospital shipped Sara and Rose back to France.

When Dib finally found out what had happened, he went to his congressman whose intervention brought Sara and Rose to Detroit. “By the time Sara joined her husband, she had crossed the Atlantic Ocean three times.” (15)

This pictorial history is full of such stories, sometimes triumphant, like that of the Abdallas, and sometimes heartbreaking like that of Ismael Shamey, who worked for forty-four years at Ford where he died of a heart attack on his final day of work, his 65th birthday. “Since he was not `officially’ retired yet, his family never received his pension.” (14)

It is ultimately due to the Detroit Arab community’s ability to generate institutions like ACCESS (Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services) that these priceless records of the miracles and struggles of everyday life have been collected.

The authors, Drs. Anan Ameri and Yvonne Lockwood, are respectively the Cultural Arts Director of ACCESS and Curator of Folklife at Michigan State University Museum.

A couple of years from now, ACCESS will open a museum dedicated to the Arab American community and its culture, where such treasures can be permanently housed. Fittingly this will be in the heart of downtown Dearborn, right across from the City Hall at Michigan and Schaefer, where Mayor Hubbard’s iron hand once ruled a city whose multinational future he could never have imagined.

ATC 100, September-October 2002