Against the Current, No. 39, July/August 1992

-

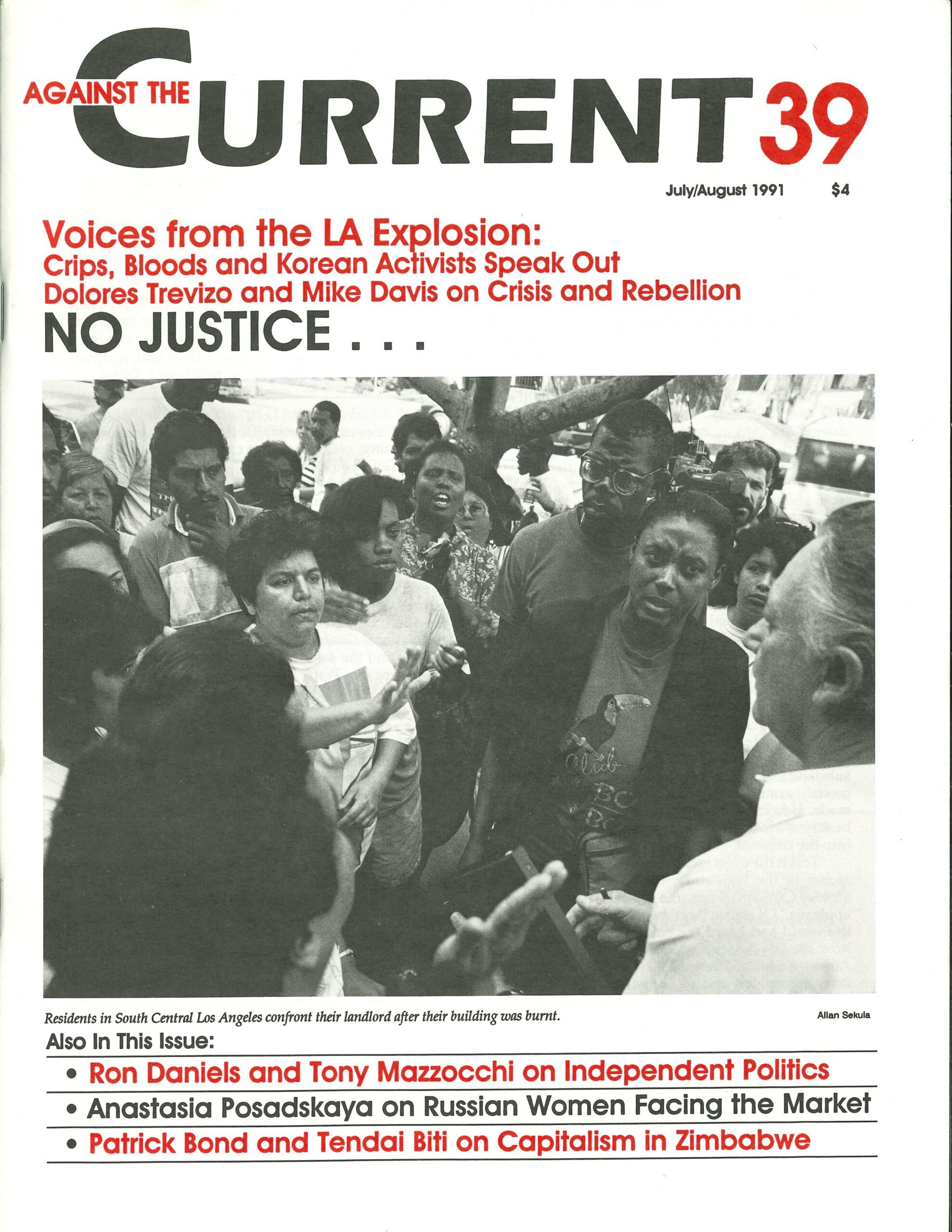

...No Peace!

— The Editors -

Race, Class and Rage

— Dolores Trevizo -

Crips and Bloods Speak for Themselves

— Voices from South Central -

Korean Perspectives

— an interview with Roy Hong -

A Diversity of Viewpoints and Generations

— an interview with Julie Noh -

Koreans Weren't Special Targets

— an interview with Kyung Kyu Lim -

Without Larger Programs, There Are No Solutions

— an interview with Kye Young Park -

Police Riot in San Francisco

— Cheryl Christensen -

Realities of the Rebellion

— Mike Davis -

Class and the Glass Fortress

— Don Sherman -

Time for a New Party

— Ron Daniels -

Beyond '92: For a Labor Party

— Tony Mazzocchi -

UAW and the "Cat" Defeat

— Earl Silber and Steven Ashby - UAW Announces In-Plant Strategy

-

Women in the ex-USSR Today

— Anastasia Posadskaya -

Bernard Chidzero: Portrait of a Comprador

— Patrick Bond and Tendai Biti -

Background on Zimbabwe

— David Finkel -

The Rebel Girl: Fitness or Exploitation?

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: In the Year of the Perot

— R.F. Kampfer - Reviews

-

The Austin Hormel Strike Revisited

— Roger Horowitz -

Movements of the Unemployed

— Dianne Feeley - In Memoriam

-

Celia Stodola Wald 1946-1992

— Patrick M. Quinn

Don Sherman

City Of Quartz:

Excavating the Future in Los Angeles

By Mike Davis; Photographs by Robert Morrow

New York: Verso, 1990, 440 pages, includes notes, indexed.

WELCOME TO MODERN Los Angeles, where urban planners once envisioned parks and city pavements as a way to effectively mingle classes in order to soften class antagonisms, where now privatization of public space is a city goal.

The most prominent Marxist urban planning theorist in the United States, David Harvey, wrote that any general theory of a city must “somehow relate the social processes in the city to the spatial form which the city assumes.” Conceptualizing cities is manifestly complicated, and only a writer with imagination and clarity of vision can begin to bring a city to life.

Mike Davis succeeds in bringing Los Angeles to life in City of Quartz, an analysis of the fastest growing metropolis in the advanced industrial world. This regional megapolis can be said to encom- pass an area extending south into a corner of Baja California, Mexico, west to the Mojave desert, and north to Santa Barbara.

Currently, 15 million people live in the area and its population is expected to increase by another 8 million in the next twenty-five years.

Davis takes on the prodigious task of attempting to reveal the true nature of Los Angeles by peeling off layers of its complexity and making it comprehensible. With only a few exceptions, he succeeds.

The fact that Davis teaches Urban Theory at the Southern California Institute of Architecture doesn’t necessarily qualify him to accurately assess the social forces that make up such a diverse city as Los Angeles. Davis adds the perspective of a Southern California native as well as a radical working class interpretation to his academic research.

Before accepting a trade-union scholarship to study economic history at UCLA, Davis worked as a meatcutter and long-distance truck driver. This perspective is especially evident in his vivid portrayal of work and social conditions of Fontana, a true blue-collar city in eastern Los Angeles County.

From Desert to Open-Shop Babbitry

Davis begins City of Quartz with a history of the Anglo invasion of Los Angeles. promoted by pioneer real estate speculators who vowed to make the insignificant desert town bigger than San Francisco. In the late 19th century, attracting the “affluent babbitry of the Middle West” took incredible chutzpa.

Nevertheless, the sellers of dreams succeeded. Promoters, led by the notorious General Otis, owner of the Los Angeles Times, sold “sunshine and the open shop” to thousands of small investors in the East. After 35 years of almost incessant boosterism, Los Angeles grew from a town of several thousand to a city with a population approaching one million.

Here was a city built on the fortunes of real estate capitalism, but dependent on the myth of “happy peasants” and submissive workers.

When class warfare threatened to intrude on this capitalist dream world, Los Angeles boosters were only too glad to invent newer fantasies. During the great Pullman strike of 1894, General Otis instructed his city editor to organize the first Los Angeles Fiesta as a public distraction, when he feared “that the local Pullman strikers might draw out other workers in a general strike.”

These capitalist-generated myths undoubtedly made Los Angeles a city of contradictions, leading Louis Adamic (Dynamite: The Story of Class Violence in America, 1929) to emphasize “the centrality of class violence in the construction of the city.” Davis expands on this theme and points out that class conflict still continues beneath layers of myths and fantasies about Los Angeles.

Latter Day Mythologies

In contrast to the early boosters who advertised Los Angeles’ sunshine and docile workforce, today’s more sophisticated myth makers glamorize the “upside of current social polarization.”

The Hollywood myth co-opts the energy and intellectual vitality of inner-city life and working-class culture; and a broad spectrum of artists and performers willingly allow purveyors of culture to sell their polished images and messages. As a result, corporate monies, including billions from Pacific Rim economies, dominate “every level of cultural superstructure.” Davis points out that this corporate megadeveloper stranglehold on cultural expression is only one more indication that Los Angeles’ future lies in a bleak Blade Runner-like scenario.

Davis’ pessimism is reflected in his analysis of the relations among elites competing for power over the city. His sardonic humor underscores the backroom deals and Chinatown-like schemes that put the Downtown elites in power.

These Downtown elites made their monies on real estate, which, in order to grow, required a continuous transfer of wealth from the rest of the country, oil, open-shop repression of workers and minorities, and complacent babbitry of an increasing Anglo population (except on one occasion during the Depression, when many of the once middle class turned their anger and confusion about their deteriorating fortunes into votes for the Socialist gubernatorial candidate, Upton Sinclair).

The success of the Downtown elites to enrich only themselves in this most dynamic of cities lasted up until the 1940s, when a combination of Westside real estate speculation, the beginnings of Los Angeles’ dependency on the emerging military industrial and aerospace industries, and the arrival of the omnipresent automobile dispersed the nodes of economic power.

Pluralism of the Elites

The Downtown elites were also forced to compete with the new mall developers, the savings and loan empires and the aggressive Westside merchant builders for economic and political power.

The dispersion of economic power was indisputable by the 1950s, when the Los Angeles City Council defeated a rapid rail system proposed by the Downtown establishment to enhance its property values. Ironically, the rail system was labeled a socialist plot by outlying commercial interests. General Otis would have never let a political defeat like that happen.

For a number of years, the Downtown and Westside power structures were separate and distinct. However, as Harvey, the Marxist planner, explains, alliances among elites are made in defense of social reproduction (of both accumulation and power over labor). The united elites then “typically engage in community boosterism which strives to create community solidarity in defense of local interests.” The Downtown and Westside elites eventually entered into such an accommodation.

As Davis sees it, Tom Bradley, the present Mayor of Los Angeles who was supported by Westside monies in his first mayoral race against incumbent Sam Yorty in 1969, played an important role in bridging the gap between the Westside and Downtown formations of city power. Davis

clearly shows that the cautious, opportunistic Bradley betrayed the Black poor of South Central Los Angeles in favor of Downtown business interests and his Westside benefactors.

This is not surprising in a powerful capitalist society. Bradley, however, is characterized as being particularly villainous, since he “chose to accommodate the redevelopment agenda of the Central City Associates” and unhesitatingly endorsed unrestricted growth while ignoring the interests of the Latin and Black communities, which formed Bradley’s electoral base.

Davis laments that the economic ghetto of South Central Los Angeles is “markedly disadvantaged even in the receipt of anti-poverty assistance, coming in far behind West Los Angeles and the Valley in access to vital human services and job training funds.”

Horror and Hollywood

In one chapter, “The Hammer and The Rock,” Davis’ anger surfaces as he describes the Los Angeles Police Department’s (LAPD) repression over the Black ghetto. The Hollywood/noir scenes become reality when he recreates a SWAT team’s storming of an alleged crack house in Central Los Angeles, while Nancy Reagan and Police Chief Daryl Gates nibbled “fruit salad in a luxury motor home emblazoned `The Establishment'” across the street for publicity.

As Nancy Reagan viewed the carnage of the drug bust, she contemptuously regarded the fourteen arrested Blacks lying handcuffed at her feet and said, “These people in here are beyond the point of teaching and rehabilitation.”

The scene has the elements of an absurd Saturday Night Live satire. But to the Black community, it was all too real.

Throughout the book, Davis points out that racism has always been a predominant ethos of Los Angeles’ ruling elites. He quotes Langston Hughes. who worked as a Hollywood writer, “So far as Negroes are concerned, Hollywood might just as well be controlled by Hitler.”

According to Davis, first under the leadership of Chief Parker then his protege Daryl Gates, the LAPD intensified its extraordinary repression in the ghettoes. The Black working class’ fear of gang violence muted protests against individual human rights violations ordered or sanctioned by LAPD Chief Gates or City Attorney Hahn.

Notwithstanding the Christopher Commission’s recent criticism directed toward Gates because of the Rodney King beating, the elites of Los Angeles have always supported brutal tactics to repress minorities and workers. The homeless are also being terrorized by the LAPD to keep out of the elite areas of Downtown Los Angeles.

The Politics of Urban Space

Davis’ background as an urban theorist gives him an insight on the aims of contemporary architecture. He clearly shows that the use of space in cities has always had an ideological purpose and that the ideas and visions of the prevailing elites in Los Angeles direct the structure and shape of the city.

This desire for physical separateness can be seen in the developing architecture of the city. Davis observes that Los Angeles was redeveloped to prevent any “unwanted exposure to Downtown working class environments” by the elites; and post-liberal Los Angeles is now obsessed with “physical security systems and, collaterally, with the architectural policy of social boundaries.”

When Davis writes that the designers of malls and pseudo-public spaces set up architectural and semiotic barriers to filter out undesirables, the reader can easily accept his conclusions. Sparse photographs by Robert Morrow of alienating fortress-like malls and libraries accompany the text and show an increasingly fearful city.

Of course, the racist fears only contribute to the continuing indiscriminate police repression of Black and Latino communities. This repression is consistently supported by middle-class homeowners’ associations.

Davis can’t quite bring himself to be serious about the political acumen guiding these powerful associations. He characterizes the ideology of the homeowners’ associations as coming from the school of NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard).

Davis develops the argument that racial covenants and hostility to Blacks helped to ensure huge areas of white single family housing in the San Fernando and San Gabriel valleys, the struggle of white homeowners in the 1940s and ’50s. More recently, with the explosion in property values, homeowners are simultaneously involved in tax revolts, organizing against school busing and integration, and protests to stop accelerated development. Davis presents the improbable image of overweight middle class homeowners mounting barricades with a revolutionary fervor to defend their property values.

Utopia and Nightmare

The homeowners’ anger must be understood in the context of Davis’ perception of Los Angeles: that the city plays the double role of utopia and dystopia for advanced capitalism.

Homeowners want to see their Ozzie-and-Harriet dream of Los Angeles come true. Reality, however, always stands in their way.

Although Davis doesn’t take the homeowners’ rationales seriously, he does understand their power. It is a power that bemuses Davis, but also makes him wary of its potential for subjecting the homeowners’ narrow views on the entire Southern California community.

Davis is not bemused, however, when he discusses Kaiser Steel, the city of Fontana, and the selling out of steel workers. Fontana lies sixty miles east of the City of Los Angeles. It was essentially shaped by one of Roosevelt’s favorite industrialists, Henry Kaiser, who used his political favors to build an immense steel plant in the shadow of the San Bernadino mountains.

With the arrival of steel workers in the early 1940s, Fontana was transformed from a farming community into an industrial city. Unlike most other areas in Southern California, Fontana became a union town. Davis only cursorily develops the struggles workers must have had at their work place and within the union. Still, his pro-worker sentiments are evident as he describes the mounting economic problems that forced Kaiser Steel to eventually liquidate its Fontana operations.

A Morrow photograph of the devastated ruins of the steel works evokes the pain of the loss of 8,000 jobs. Davis’ anger is directed at Reagan-era corporate raiders who dismantled and looted the steel works, and at Kaiser Steel managers who have recently threatened workers’ pensions.

Davis’ feelings about the promise and the reality of life in Los Angeles and Southern California are probably accurately reflected in the last chapter, “Junkyard of Dreams.” He finds the current situation to be surreal, and directs his anger at the repressive capitalism controlling Los Angeles, and mourns Los Angeles’ missed opportunities.

Davis sees the many worlds of Los Angeles with great clarity. He just doesn’t see the one he wants to live in.

July-August 1992, ATC 39