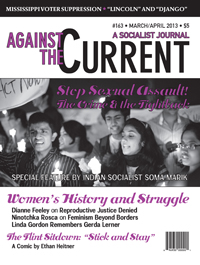

Against the Current, No. 163, March/April 2013

-

More Gridlock -- Or Worse?

— The Editors -

Gun Control: Carnage in Context

— The Editors -

Lincoln, Django and Abolitionism

— Malik Miah -

Colombian Workers Injured and Fired

— Diana C. Sierra Becerra -

Immigration Reform: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

— Joaquin Bustelo -

Voter Suppression Hits Mississippi

— Bill Chandler - Rallying to Stop the Keystone XL Pipeline

-

Occupy Cincinnati as a Case Study

— Ursula McTaggart -

Inside the Capitalist Crisis

— Charlie Post -

What Is the "Working Class"?

— Sam Friedman - Women in the Struggle

-

Reproductive Justice Needed

— Dianne Feeley -

Feminism's March from Nation to Home

— an interview with Ninotchka Rosca -

The Struggle Against Rape and Sexual Assault

— Soma Marik -

Post-war Left Feminism

— Robbie Lieberman -

Gerda Lerner, 1920-2013

— Linda Gordon -

The Century of Rosa Parks

— Dianne Feeley - Reviews

-

Indians, Leftists, and Rebellion in Bolivia

— Kevin Young -

The Evolution of Evolution

— Ansar Fayyazuddin -

The Metaphors of Movements

— Barry Eidlin -

A Thanks

— The Editors

Barry Eidlin

Guerillas in the Industrial Jungle:

Radicalism’s Primitive and Industrial Rhetoric

by Ursula McTaggart

State University of New York Press, 2012, 247 pages, $24.95 paper.

MOVEMENTS NEED METAPHORS. While they address very concrete social problems that affect people’s lives in very real ways, it is movements’ imagery and rhetoric that incite people to action and give movements cohesion. We saw this most recently with the Occupy movement and its powerful image of the 99% versus the 1%, but there are many examples: “Teamsters and Turtles” at the World Trade Organization protests in Seattle, Rosa Parks sitting on the bus in Montgomery, self-immolating monks protesting the Vietnam War, to name a few.

Metaphors help make sense of huge, systemic problems whose scope can be beyond our individual comprehension. They provide a vision of a different, better world that makes joining the movement seem like an appealing, worthwhile thing to do. Without metaphors, movements lack meaning.

Although movements deploy a variety of metaphors to mobilize people, they often draw upon similar repertoires of images. At the most general level, think of the raised fist, the locked arm, or the manifesto held aloft. More specifically, movements will borrow imagery and rhetoric from other movements. For example, striking sanitation workers in California this past summer carried picket signs that declared: “I AM A MAN,” evoking the 1968 Memphis sanitation strike, a key civil rights battle of that era.

Such acts of borrowing can be deliberate on the part of movement leaders, or emerge organically. They can help to broaden support, claim legitimacy, and energize movement activists. At the same time, they connect movements across time and space, creating a sense of something bigger than the immediate events of the moment. Over time, repeated borrowing can create a kind of movement tradition, a set of rituals that identify people as being part of a community, sharing similar goals and beliefs.

In Guerillas in the Industrial Jungle: Radicalism’s Primitive and Industrial Rhetoric, Ursula McTaggart explores what she identifies as two enduring metaphoric repertoires for radical Left movements in the United States: the “primitive” and the “industrial.”

Temporally, the primitive looks to the past. Employing a narrative of degeneration, it both “invokes nostalgia for a lost past” and suggests “that we return to the past for our solutions.” Conversely, the industrial looks to the future. Advancing a narrative of human progress, it holds out the idea of “the promise of technology helping people to construct a better world.”

Radicals Reclaiming Metaphors

Although primitive and industrial repertoires differ temporally, McTaggart explains that they are also conceptually linked. Both articulate utopian visions of a better world, and frequently co-exist within movement rhetoric. Importantly, in the U.S. case, both are “steeped in the history of race.” (2)

Discourses of primitivist racial inferiority have been closely tied to policies of racial domination, from “Indian removal” to slavery and Jim Crow, to more recent discussions of President Obama’s Kenyan ancestry. But as McTaggart points out, industrial metaphors are woven into a narrative of progress and change, and in the U.S. context that narrative is also fundamentally about race.

What interests McTaggart in her book are the ways in which radical movements reclaim and reprogram primitive and industrial metaphors to create positive images around which to mobilize.

Her primary focus is on select radical movements of the 1960s and ’70s, with a concluding chapter examining one more contemporary movement. However, she veers away from many of the movements most closely identified in the popular imagination with the 1960s. There is little about SDS, SNCC, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the antiwar and feminist movements, or the Weather Underground, although she does delve into the history of the Black Panther Party.

For the most part, her subjects are lesser-known but important players in the history of the postwar U.S. radical left. In addition to the Panthers, there is the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and its various shop-floor “Revolutionary Union Movements” (RUMs), the Black Arts Movement, small Trotskyist-influenced “industrializing” organizations such as the International Socialists and the Socialist Workers Party (members of which later went on to found Solidarity, the sponsor of this magazine), and contemporary groups of anarchists who identify as “primitivist.”

The group of subjects is somewhat disjointed, although McTaggart does show how they each deployed primitive and industrial rhetoric. She does this both through interviews with surviving subjects, as well as textual analysis of pamphlets, images, speeches, and contemporaneous works of fiction.

McTaggart’s interpretive strategy is at its best in her analysis of the Panthers and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. The chapter on the Panthers opens by posing the interesting question of why, after being tarred as inferior, “primitive” beings by white racists for centuries, would a Black radical movement embrace primitive imagery and claim it as its own?

McTaggart provocatively argues that, in adopting such imagery, the Panthers were critiquing “both the racist Western binary between civilization and ‘primitive’ life and the Marxist notion that the industrial working class was the key to socialist revolution.” Instead, “[t]hey created a new urban ‘primitive’ fraught with racist history but essential to defining a new vision of black radicalism.” (20) Indeed, the “urban primitive” look combined the animalism of the panther with the decidedly modern, urban look of berets and leather jackets.

Interestingly, McTaggart creates parallels between the Panthers’ use of primitive imagery and the aesthetic of the Black Arts Movement (BAM). The two movements are usually considered opponents, with the Panthers embodying “revolutionary nationalism” as opposed to BAM’s “cultural nationalism.”

Personal animosities between certain movement leaders exacerbated the perceived opposition between the groups. However, McTaggart shows that, rivalries aside, the two were actually closely linked. Materially, members of both lived together and participated in the same events. Culturally, both deployed variants of primitive or tribal imagery to build support and claim greater authenticity.

Similarly, with the League, McTaggart shows how they blended primitive and industrial metaphors in their organizing, particularly with their frequent description of the factory as an “industrial jungle.” In doing so, they were not only linking with an organizing tradition going back to Upton Sinclair, but creating a new identity for workers, an identity that blurred the lines between urban and industrial, between school and factory, between community and factory.

This identity suited the reality of League members’ existence: “Members were students, working-class people, full-time activists, and professionals all at once. They shifted from one identity to another or claimed more than one simultaneously.” (71) In this way, blending the primitive and industrial created a broader, more appealing movement.

As with her chapter on the Panthers, McTaggart makes interesting connections between the League’s political activism and its art. Like the Panthers, the League had fraught but close connections to the BAM, and sought to foster revolutionary Black art through its own publishing house and production company.

League member Glanton Dowdell painted a famous mural in Detroit’s Shrine of the Black Madonna, and League publications regularly featured poetry, including the signature “Our Thing is DRUM” [Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement]. Conscious of the important links between political and cultural activism, the League sought to build its movement on both fronts.

Problematic “Primitivism”

While the chapters on the Panthers and the League offer valuable insights into the relations between metaphors and movements, the subsequent chapters on socialist groups “industrializing” into factories and “primitivist” anarchists are less satisfying.

Whereas the chapters on the Panthers and the League blend analysis of the actual movements’ political and cultural rhetoric, those on the industrializers and primitivists awkwardly juxtapose discussion of movement activists’ rhetoric with textual analysis of literary texts completely separate from those movements: “neo-slave narratives” in the case of industrializers, and speculative fiction by Octavia Butler and Nalo Hopkinson in the case of the primitivists.

McTaggart asserts that these literary juxtapositions “create a theoretical perspective from which to view the socialist industrializing project [and by extension the primitivist project].” (104) But one gets the sense in these chapters that the literary analysis is largely there because books by professors of English must include literary analysis.

The analysis itself is plausible and well done, but contributes little to understanding the actual movements. The second half of the book then pulls the reader in multiple directions at once, ultimately distracting from the author’s overall project.

Unlike the Panthers and the League, which blended primitive and industrial rhetoric to create new hybrid identities, industrializers and primitivists largely stuck to one metaphor or the other.

McTaggart’s analysis of how activists in these movements negotiated the challenges of fitting their rhetoric to their realities constitutes the strongest parts of these chapters. The stories of IS and SWP members are particularly evocative in this regard, as they recount their struggles as radicalized ex-students who were trying to negotiate the tricky terrain of inhabiting the new —and often idealized — identity of the worker, the embodiment of the industrial vision.

Take for example the experience of former SWP members Paul LeBlanc and Dianne Feeley, who were assigned by the party to work at a Ford plant in Metuchen, New Jersey. During their time in the plant, the company announced that a nearby plant was closing, and higher-seniority workers from that plant, described as mostly white and male, would displace lower-seniority workers at the Metuchen plant, which included more women and people of color.

The party’s political training left them ill equipped for negotiating between the competing goals of defending union rights, such as seniority, and advancing racial and gender equality. Feeley expressed her exasperation: “how could we have a position on the Iranian revolution but not have a position on what should be happening in our own plant?” In the process, Feeley and LeBlanc learned lessons about the complexities of working-class politics that were difficult to learn through more traditional forms of political training.

These strengths of the individual stories notwithstanding, the problem remains that the book claims to explore the interplay between primitive and industrial rhetoric. In this, the author’s strategy of simply juxtaposing the two falls short.

Although taken as a whole Guerillas in the Industrial Jungle lacks cohesion, readers looking for insightful analysis of the culture and politics of 1960s Black liberation movements will be well served by reading the first half of McTaggart’s book.

Those interested in delving into the personal experiences of socialist activists who sought to integrate into life on the shop floor will also find much of interest in the chapter on the industrializers. And readers interested in exploring how “primitivist” anarchists negotiate the contradictions of espousing an ideology that preaches a return to a distant past using technologies of the present will likely find the penultimate chapter intriguing.

March/April 2013, ATC 163