Against the Current, No. 73, March/April 1998

-

The IMF's Imperial "Reform"

— The Editors -

Random Shots: The NASA Seniors Tour

— R.F. Kampfer -

"I Don't Want To Wait Twenty-six Years for Justice" Roisin McAliskey in Limbo

— Stuart Ross -

Political Prisoner Dita Sari

— Emily Citkowski -

The Jericho `98 March: Amnesty and Freedom for All Political Prisoners

— Steve Bloom - For International Women's Day

-

The Struggles of Women in Brazil

— Dianne Feeley interviews Tatau Gadinho -

Poverty & Oregon's Welfare Reform

— Johanna Brenner -

Activists Speak Out: The Poverty of Welfare Reform

— Interview with Theresa el-Amin -

Activists Speak Out: The Poverty of Welfare Reform

— Interview with Amy Hanauer -

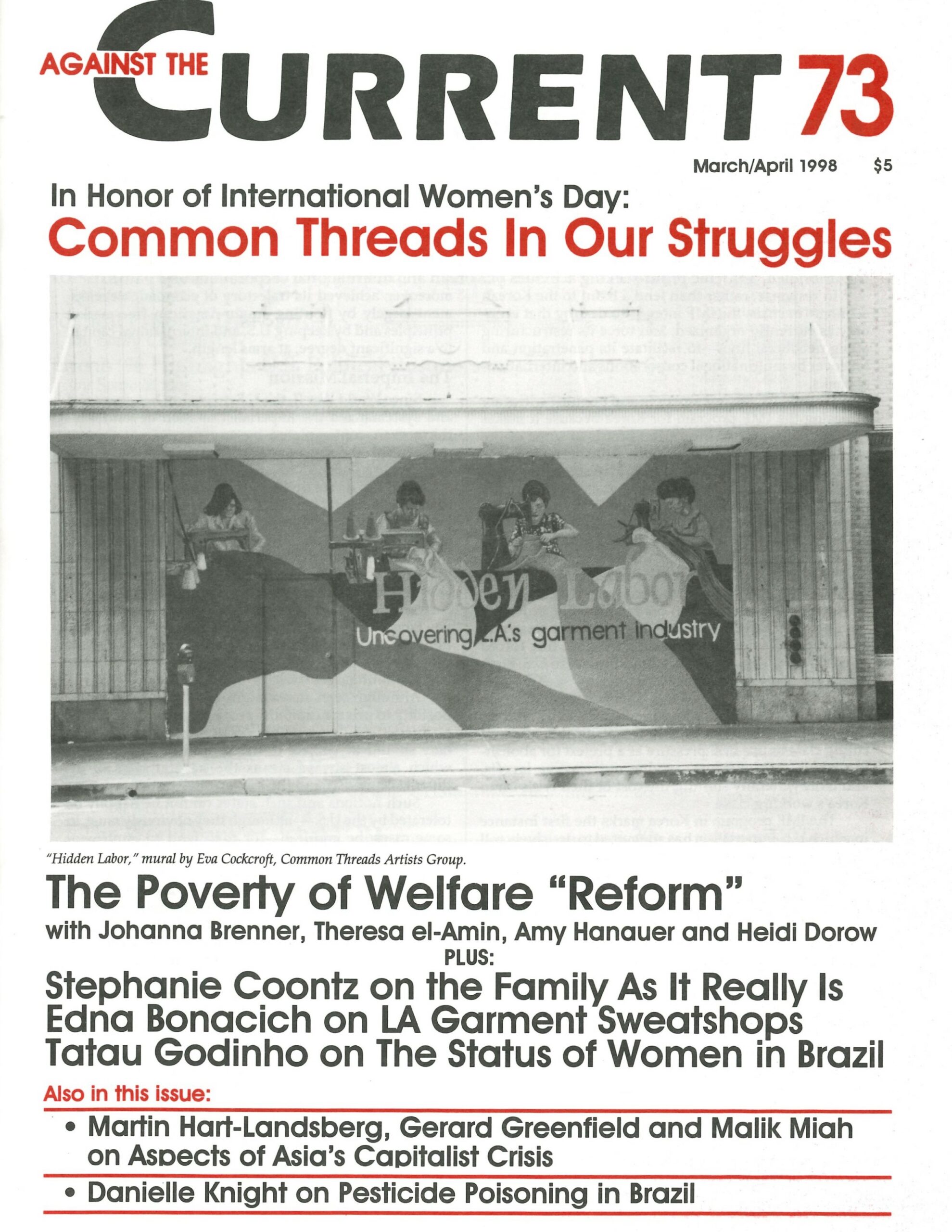

LA Sweatshops: Common Threads In Struggle

— Edna Bonacich -

Activists Speak Out: The Poverty of Welfare Reform

— interview with Heidi Dorow -

The Family As It Really Is

— Stephanie Coontz -

The Rebel Girl: We Shoot, We Score — At Last!

— Catherine Sameh - Asia's Capitalist Boom and Bust

-

Causes and Consequences: Inside The Asian Crisis

— Martin Hart-Landsberg -

Suharto's Days Are Numbered: Protests, Riots Rise as Clinton and IMF Back Dictator's Regime

— Malik Miah -

The World Bank's The State In A Changing World: The Global Politics of TQM

— Gerard Greenfield -

Transnational Capital and the State in China: Partners in Exploitation

— Gerard Greenfield - Reviews

-

The Destiny of A Revolution

— Donald Filtzer

Dianne Feeley interviews Tatau Gadinho

TATAU GODINHO IS a member of the National Women Secretariat of the Workers Party (PT) and of the leadership of the PT in the state of São Paulo. She has been an activist in the women’s movement for many years. Dianne Feeley interviewed her for ATC.

ATC: How has the Cardoso administration brought changes to the Brazilian economy, and what is their impact on women?

Tatau Godinho: The government of President Fernando Henrique Cardoso, which took office in 1994, has developed an economic and political program completely in accord with the main trends of neoliberal policy in the world.

This economic plan was put forward by the previous government in mid-1994, when Fernando Henrique Cardoso was Minister of Economics. It aimed at cutting state intervention in the economy; opening the Brazilian economy to the world market in a completely dependent way; reducing tariffs; offering extremely high rates of interest and keeping the Brazilian currency overvalued. Our economy has been extremely linked to international finance circuits, which puts us in a very fragile position to face the crises in the international market, as the crash last October showed.

The government has privatized some of the most important state-owned enterprises but has not yet finished its privatization plan. It has cut the number of public employees and also cut federal financing for public services. Labor relations legislation was another target for the government’s attack on the gains the workers and trade unions won in the 1980s (when a new constitution was approved). The pension and retirement system was altered.

From the very beginning the government has not had any special program toward women as a specific sector of society. But the cutbacks in public services, the growing unemployment and the huge concentration of income in the country have had a severe impact on women.

ATC: In what way does this economic program affect women?

TG: In fact, the economic hardship has had an important effect on women, because they are not only among the layers of the population who receive the lowest salaries but also remain trapped in the sexual division of labor, which places on their shoulders the major responsibility for raising the children and taking care of the welfare of the family.

In terms of public policies there has been no development of services or programs in areas of women’s specific needs or interest. Nothing has been done to prevent violence against women.

In the 1980s some special policy departments were set up to receive complaints from battered or discriminated women, victims of violence or discrimination. Since the police is run by the various state governments, those departments are found on the state level. They are still very insufficient in number and without an adequate budget—the great majority are now in precarious condition. There has been no federal support of any kind either to improve their functioning or to create centers for social, economic and psychological assistance to women.

For over a decade the national program for women’s health has remained a piece of paper stating good intentions, while the general conditions of public health in the country have worsened. Brazil today has aa appalling maternal mortality of 156 deaths per 100,000 live births.

There have been no measures related to improving women’s work or employment. Just the opposite, actually, as unemployment has grown all around the country. he pressure to accept cuts in salary and benefits is very strong.

ATC: How have the feminist movement and other social movements fought back?

TG: There has been resistance, but the conditions of struggle are much more difficult now than they were in the 1980s. The social movements in general have lost a lot of their strength and organizational capacity.

Besides, the social and economic conditions are quite different now