Against the Current, No. 223, March/April 2023

-

Women's Rights, Human Rights

— The Editors -

Lives Yes, Pipelines No!

— Rebecca Kemble - Salvadoran Water Defenders

-

Killings by Police Rose in 2022

— Malik Miah -

View from the Ukrainian Left

— Denys Bondar and Zakhar Popovych -

Witness, Resilience, Accountability

— interview with Rabab Abdulhadi - Palestine Solidarity Activism Under Fire

- The Horror in Occupied Palestine

-

Nicaraguan Political Prisoners Freed, Deported

— Dianne Feeley and David Finkel -

Stuck in the Mud, Sinking to the Right: 2022 Midterm Elections

— Kim Moody -

Heading for the Ditch?

— David Finkel -

Paths to Rediscovering Universities

— Harvey J. Graff - International Women's Day, 2023

-

Demanding Abortion Rights in Russia

— Feminist Anti-War Resistance/ FAS (Russia) -

Before & After Roe: Scary Times, Then & Now

— Dianne Feeley -

Abolition. Feminism. Now.

— Alice Ragland -

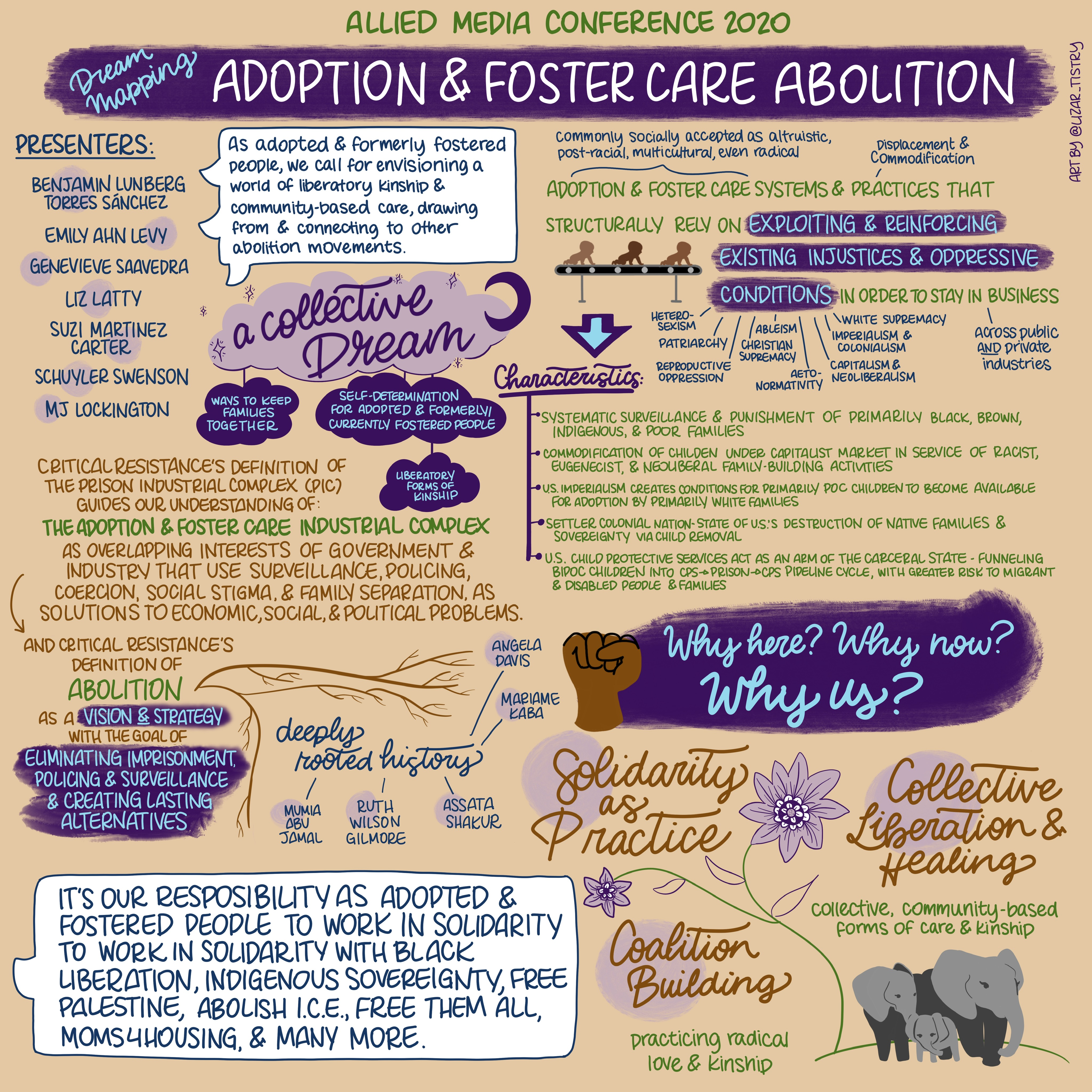

#Adoption Is Trauma AND Violence

— Liz Hee - Reviews

-

Radical Memory and Mike Davis' Final Work

— Alexander Billet -

A Revolutionary's Story

— Folko Mueller -

James P. Cannon, Life and Legacy

— Paul Le Blanc -

The World of Professional Boxing

— John Woodford -

A Powerful Legacy of Struggle

— Jake Ehrlich -

War and an Irish Town

— Joan McKiernan - In Memoriam

-

Mike Rubin 1944-2022

— Jack Gerson

Liz Hee

NATIONAL ADOPTION AWARENESS Month, aka NAAM, is a month for adopters, agencies, and Child Protective Services to promote adoption as an act of love. On the first day of NAAM 2022, adopted people on social media across the globe started the month by introducing the hashtag #AdoptionIsTraumaAND.

This was a “by us, for us” campaign with the goal of “shared language, different ways of thinking about adoption and other systems of family separation, and connecting them across other struggles for liberation.”

The campaign came out of a growing community of self-identified adopted and fostered abolitionists with shared analysis of the violence of systems of family regulation and policing. While adopted and fostered (also self-identified as “former foster youth”) people have advocated for adoption and foster “care” to be recognized as a trauma, this campaign aimed to move community conversations and organizing beyond individual experiences.

Throughout the month, the #AdoptionIsTraumaAND campaign identified adoption as violence, colonial, racial capitalism, commodification, ableist, cis-hetero-patriarchal, policing, and genocide. These implications indicate a growing analysis of adoption that has the potential to shift toward an analysis of systems of exploitation and oppression more broadly.

The socialist framework of internationalism from below offers a helpful starting point from which such an analysis could be further developed. Socialism itself, however, as a political ideology and practice, lacks a critical approach to adoption. This article seeks to demonstrate why a critical approach to adoption matters for an international socialism from below.

A Critical Approach to Adoption

Dominant narratives, mainstream media, and invested actors continue to extol adoption as a form of “family creation based in love instead of biology.” However, reducing one’s understanding of adoption to the practice of raising a non-biological child ignores how the institution of adoption is a specific system based in violence, inequality, and the commodification of children.

In contrast to the idea that adoption is a form of expansive kinship that challenges nuclear family norms, its institutionalization is constitutive of the historical construction and privatization of the family as developed under class society.

At the start of the 20th century in the United States and Western Europe, and continuing today throughout the world, so-called progressive reforms have proposed fostering and adoption as the solution to indentured labor and institutionalization of children.

While such reforms are intended to provide children with the loving care of “home life” (declared the “highest and finest product of civilization” by the

first White House Conference on Children in 1909), they rather expose the violent contradictions of creating a family through the destruction of another, as well as acting in the “best interests of the child” while upholding property rights to children.

In the United States, the modern history of fostering and adoption is inseparable from the oppression of women and birthing people, the genocide of Indigenous peoples and eugenics, slavery and the destruction of Black families, and Christian supremacy, white saviorism, and U.S. imperialism.

Beyond its historical context and development, the ongoing practice of adoption as an institution is questionable at best, from the transnational and geopolitical, to the interpersonal and individual. Today, the violent trauma of adoption has been well-documented by adopted people and researchers.

In addition to the tragic stories that make headlines when an adoption “goes wrong,” such as abuse and secondary abandonment, adopted people and researchers have identified common themes around identity and grief regardless of whether the adopted person had a “good” or “bad” experience.

While the physical separation and loss of heritage is a traumatic violence in itself, it is compounded and prolonged by practices like sealed records, name changes, and erasure of the first/biological parents from the birth certificate. The profit-oriented and geopolitical agendas of nation-states and private actors continue to operate on scales of violence and coercion in the name of family creation, the affective outcomes of which are often unconsciously internalized within the adopted person.

Adoption, and thus the adopted person, is a site of constant violence that inhabits and exposes many of the most devastating aspects of global capitalism.

Why It Matters

The socialist movement’s lack of a critical analysis of adoption has resulted in defaulting to mainstream acceptance of it at best, and actively promoting it at worst. For example, the Fourth International’s 2003 World Congress statement “On Lesbian/Gay Liberation,” asserts that “[we] are in favor of the right of all people to be able to adopt children or gain custody of children.”

At first glance, this is a statement in defense of equal rights for Lesbian and Gay peoples. Such a position should be indisputable and it is not my intention to challenge it generally. However, the specific invocation of the right to adopt requires further investigation.

While socialism neglects adoption as a site of violence and struggle, it has a history of challenging parental property rights to children. In line with this tradition, the 1979 Fourth International’s “Socialist Revolution and the Struggle for Women’s Liberation” statement demands “the abolition of all laws granting parents property rights and total control over children.”

This position against parental property rights, however, is in contradiction with the above statement supporting the “right to adopt,” as adoption itself upholds and further enshrines parental property rights.

Adoption itself is a manifestation of the family’s contradictory position as both a site of love and resistance that must be protected, and a site of violence that must be abolished. This contradiction is evident across struggles against systems of family policing and regulation.

For example, the Supreme Court is currently reviewing Haaland vs. Brackeen, a case in which adopters Chad and Jennifer Bracken seek to overturn the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) on the grounds of racial discrimination against their ability to adopt a Navajo child.

ICWA is a federal child welfare policy that prioritizes placing children in child welfare proceedings in the care of extended family or tribes on the basis of tribal sovereignty. It effectively limits the child welfare system’s jurisdiction while leaving its existence unchallenged.

At the same time, a growing number of people are demanding the abolition of the child welfare system writ large and its targeted destruction of Black families and communities. One of the main demands of this movement is to end the termination of parental rights, which has been used to legally sever the ties between Black parents and their children so that they are “free” to be adopted.

Thus this demand itself presents the contradiction of defending parental rights to children while also seeking to abolish a system of family policing. Similarly, the movement to abolish the child welfare system presents a contradiction in its position to protect ICWA.

The movements to Protect ICWA and Abolish CPS (Child Protect Services) are just two examples of the ways in which adoption is a site of contestation that requires navigating the contradiction between the family as a site of resistance and the family as a site of oppression. A critical approach to adoption exposes these sites as points from which to build solidarity across various struggles.

Further evident in the ways adoption is consistently used to uphold certain political agendas, such as white nationalist attacks on abortion and claims of a “domestic infant supply” problem; Texas Governor Greg Abbot’s attack on trans people and his executive order to report children accessing gender affirming healthcare to Child Welfare Services; and the transfer of children from sites of climate disaster and war via adoption, as seen with U.S. citizens adopting Haitian children and Russians adopting Ukrainian infants.

The socialist tradition of approaching material contradictions through a dialectical lens is uniquely positioned to engage adopted and fostered people with a growing critical approach to adoption in a way that centralizes experience and knowledge to “draw adequate conclusions for action.” (Mandel, https://www.marxists.org/archive/mandel/1983/03/vanguard.htm)

In turn, such centralization and collaborative work is essential for a more expansive understanding of how socialists can address in both theory and practice the contradictions between demanding the right to adopt and demanding the abolition of property relations to children, and more broadly, the contradiction of the family itself.

March-April 2023, ATC 223