Against the Current, No. 223, March/April 2023

-

Women's Rights, Human Rights

— The Editors -

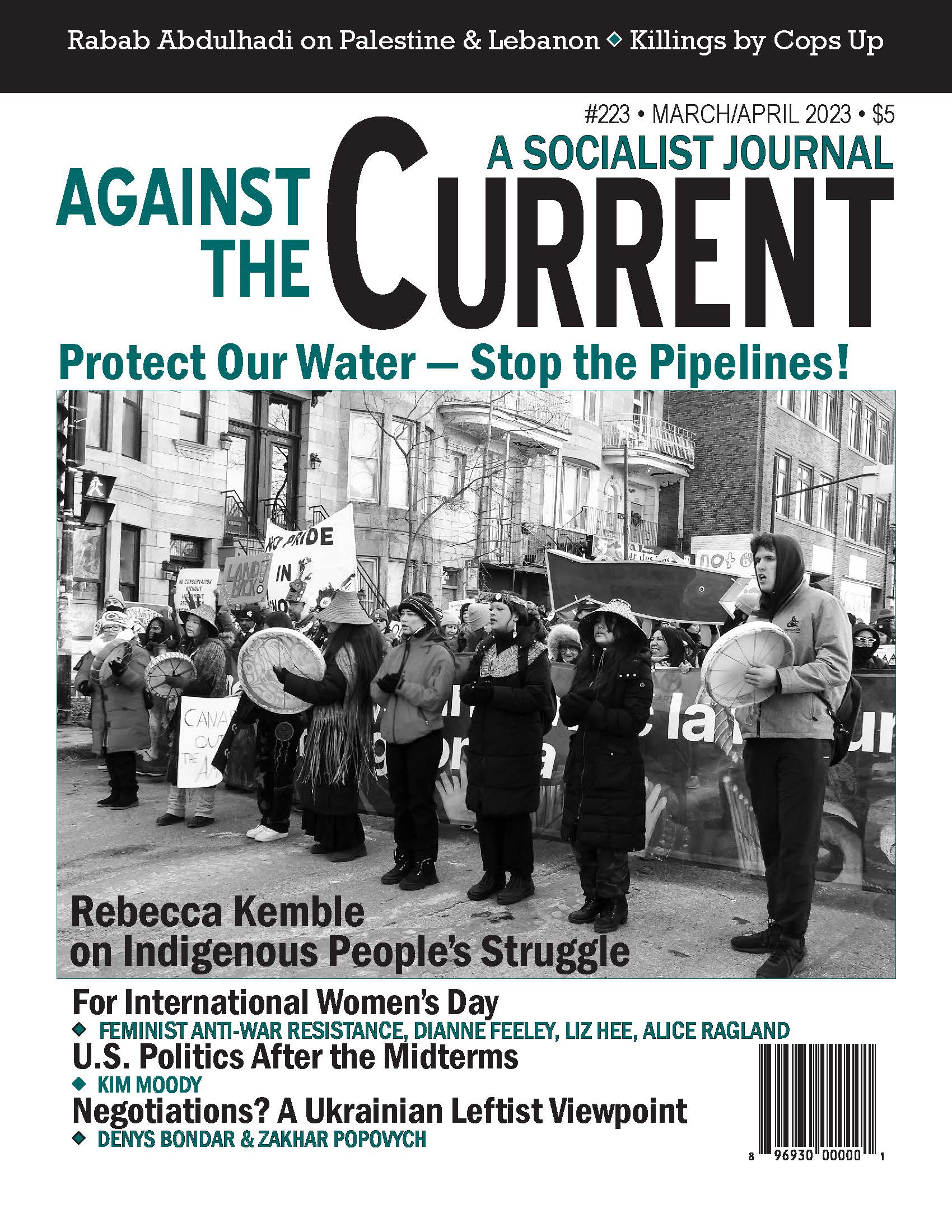

Lives Yes, Pipelines No!

— Rebecca Kemble - Salvadoran Water Defenders

-

Killings by Police Rose in 2022

— Malik Miah -

View from the Ukrainian Left

— Denys Bondar and Zakhar Popovych -

Witness, Resilience, Accountability

— interview with Rabab Abdulhadi - Palestine Solidarity Activism Under Fire

- The Horror in Occupied Palestine

-

Nicaraguan Political Prisoners Freed, Deported

— Dianne Feeley and David Finkel -

Stuck in the Mud, Sinking to the Right: 2022 Midterm Elections

— Kim Moody -

Heading for the Ditch?

— David Finkel -

Paths to Rediscovering Universities

— Harvey J. Graff - International Women's Day, 2023

-

Demanding Abortion Rights in Russia

— Feminist Anti-War Resistance/ FAS (Russia) -

Before & After Roe: Scary Times, Then & Now

— Dianne Feeley -

Abolition. Feminism. Now.

— Alice Ragland -

#Adoption Is Trauma AND Violence

— Liz Hee - Reviews

-

Radical Memory and Mike Davis' Final Work

— Alexander Billet -

A Revolutionary's Story

— Folko Mueller -

James P. Cannon, Life and Legacy

— Paul Le Blanc -

The World of Professional Boxing

— John Woodford -

A Powerful Legacy of Struggle

— Jake Ehrlich -

War and an Irish Town

— Joan McKiernan - In Memoriam

-

Mike Rubin 1944-2022

— Jack Gerson

Paul Le Blanc

James P. Cannon and the Emergence of Trotskyism

in the United States, 1928-38

by Bryan Palmer

Leiden/Boston: Brill Publishers, 2021,1208 pages; $445 hardback.

Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2022, $65 paperback.

WHAT JUSTIFIES A book of 1200 pages, which is only the second volume of the biography of someone generally seen as an obscure figure on the far left of the political spectrum? Is this a case of sectarian iconography gone mad? Is it an example of a scholar who has done an enormous amount of research but is not in control of his material? I don’t think so.

The answer: we are not dealing with a book. Between the covers of this volume are six books: (1) a continuation of Bryan Palmer’s biography of James P. Cannon in a key decade of his life; (2) a history of the first 10 years of U.S. Trotskyism; (3) a history of the social and political dynamics of the class struggle in the United States from 1928 to 1938; (4) a study of the world Communist movement through the prism of U.S. radicalism; (5) a critique of the historiography on the previous two topics; (6) the articulation of a general orientation for revolutionary activists.

Each of these carefully researched six “books” provide thoughtful analyses with attention given to their interrelationship with each other. Understanding this makes it easier, I think, to make one’s way through and engage with this massive volume.

Palmer himself defines his outlook in the Preface, elaborating on four propositions:

“First, this history reveals the red thread of continuity between early 20th-century radicalism native to the USA — epitomized by the Industrial Workers of the World and a segment of the Left Wing of the Socialist Party — and the Communist movement inspired by the Russian Revolution. …

“Second, Cannon’s life is a repudiation of the idea that American communism was always, and could only be, dominated by slavish adherence to Moscow’s directives. …

“Third, Cannon’s history in the late 1920s and 1930s, when engaged with substantively, suggests that writing on the Communist Party must confront Stalinization, which qualitatively transformed the nature of life in what was a leading United States organization of the ostensible revolutionary left. …

“Fourth, and finally, a study of Cannon in the years 1928-38 establishes that when revolutionaries adhere to principled politics, even in difficult circumstances, it is possible to make considerable headway. …”

The book contains six large and complex chapters, sandwiched between a substantial introduction, which establishes the themes that await the reader, and a conclusion.

The first chapter provides a detailed account of the early beginnings of U.S. Trotskyism in the form of the Communist League of America (CLA), with attention to initial gains and also to the explosion of Stalinist violence against CLA public meetings and those distributing CLA literature.

Depression, “Entrism” and Splits

The second chapter deals with the first incredibly difficult years of the Great Depression, fruitless appeals for Communism’s Stalinist mainstream to reform itself, and debilitating factional conflicts within the CLA. The third covers the revitalization of Trotskyist forces brought on by renewed class struggle of the 1930s, combined with a decisive break from the Communist mainstream generated by Stalinism’s inability to play any positive role in preventing Hitler’s rise to power.

The fourth chapter covers, in considerable detail, the decisive role of CLA members in leading the 1934 Minneapolis Teamsters Strike to triumphant victory (also covered in Palmer’s earlier study, Revolutionary Teamsters).

In the fifth chapter, Palmer, tracing an international orientation of Trotskyist forces to connect and in some cases merge with radicalizing forces on the Left, covers the fusion of the CLA with A.J. Muste’s American Workers Party, and then the Trotskyists’ entry into, experience within, and tumultuous expulsion from Norman Thomas’s Socialist Party of America.

Palmer covers this ground in greater depth and detail than ever attempted before, and he comes to conclusions that challenge the most common narrative.

“A balanced assessment of the actual strengths of the Socialist Party and how its fractured factions responded to Trotskyism’s political challenges, reveal complexities not always evident in the usual castigations of ultra-left, sectarian ‘splitters.’

“Trotskyists did not so much ‘wreck’ a Socialist Party as provide a mirror into which its staid leadership looked, only to find its image shattering as a consequence of it being forced to confront left-wing criticisms and take responsibility for its actions in stifling them administratively.”

Cannon himself believed the entry would before long culminate in such a split, yet ironically, Palmer observes, Cannon nonetheless insisted “that entryists engage in the hard work of building the Socialist Party, conducting themselves as dedicated workers in the mass mobilizations of 1936-37” — an orientation he himself carried out in California, where he was then based.

Such an approach helps explain why many rank-and-file Socialist Party members decided to go with the Trotskyists when their own leaders decided to expel “the Trotskyite wreckers.”

Popular Front and Purges

The sixth chapter overlaps with this “entrism” period, dealing with many substantial occurrences of 1936-37. One development was a shift in the policies of the international Communist movement toward what was dubbed the Popular Front – the effort to build an alliance of Communists and liberal capitalists to block the growth of fascism and defend the Soviet Union.

At the same time, Stalinism turned increasingly murderous toward revolutionary dissent (both actual and potential).

The Moscow Trials accused Trotsky of collaboration with imperialism and Nazism while putting dozens of old Bolsheviks in the dock to confess to fictitious crimes before their summary executions; tens of thousands more were sent to deadly forced labor camps.

Within the Spanish Civil War between forces of the Left and the Right (1936-39), Stalinists sought to impose their class-collaborationist policy while dealing brutally with those on their left flank. Palmer documents U.S. Trotskyist responses: challenging Popular Frontism; establishing an authoritative commission headed by philosopher John Dewey to examine and debunk the Moscow Trials; and defending the Spanish Revolution.

In addition, he focuses attention on substantial Trotskyist activity among teamsters, autoworkers and maritime workers. The book’s conclusion describes the 1938 birth of the Socialist Workers Party and the formal crystallization of the Fourth International.

This book is an irreplaceable resource for anyone seriously interested in working-class history and labor struggles in the United States, in the complexities of U.S. Communism, in the history of the Trotskyist movement, and in struggles for a better world.

Palmer’s scholarship is meticulous, thoughtful and balanced. Even where one disagrees with his judgments and conclusions, his work on Cannon and the Trotskyists is a necessary reference point.

For example, my own understanding of issues of the African American experience and struggles for Black Liberation is grounded in analyses advanced by C. L. R. James, George Breitman and Leon Trotsky — all of whom embraced the notion of “self-determination” and respect for the orientation of Black nationalism.

Palmer is critical of that current of thought, adhering to a perspective that he and others have labeled “revolutionary integrationism.” But his extensive and rich discussion of the question, providing a splendid survey of the contending positions and sources, will be valued by anyone seriously engaged with the matter.

Cannon in the Revolutionary Tradition

James P. Cannon was a founding member of the U.S. Communist Party. While his 19th century childhood in the American heartland was reminiscent of Mark Twain’s stories of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, his youth and young adulthood involved an immersion in the Socialist Party of Eugene V. Debs and “Big Bill” Haywood’s Industrial Workers of the World.

A key leader of the early Communist Party in the United States, he labored to draw its various elements together into a vibrant and effective revolutionary collective force within the working class. As international Communism of the 1920s experienced a transition from the leadership of V.I. Lenin to domination by Joseph Stalin, Cannon faced an accumulation of bureaucratic and authoritarian obstacles that undermined the efforts of U.S. revolutionaries.

Finally, he was expelled for opposing what he perceived as the bureaucratic tyranny of Stalinism, adhering instead to the “Bolshevik-Leninist” and revolutionary-democratic program of Leon Trotsky. For the rest of his life, Cannon was a leading figure in the American Trotskyist movement, and in the global network of revolutionary socialist groups gathered under the banner of the Fourth International.

The outstanding Marxist writer Harry Braverman, who broke from his mentor in the 1950s, in 1976 memorial remarks vividly described Cannon’s impact on him and other 1930s radicals:

“He spoke to us in the accents of the Russian revolution and of the Leninism which had gone forth from the Soviet Union in the twenties and the thirties. But there was in his voice something more that attracted us. And that was the echoes of the radicalism of the pre-World War I years, the popular radicalism of Debs, Haywood, and John Reed. And he spoke with great force and passion.”

(Braverman was a member of a minority expelled in 1953 from the Socialist Workers Party. His writings are available at: https://www.marxists.org/archive/braverman/index.htm, though he is best known for his 1974 classic study Labor and Monopoly Capital.)

Seen by many as “the grand old man of American Trotskyism,” Cannon has been denounced and dismissed by many others as narrow, sectarian, factional — an example that serious radicals should not follow. This volume will further stir such controversies but it seems to me that it is destined, as well, to advance scholarship and thinking on a variety of important questions.

While this book is so massive as to place it beyond the reach of many, the person of Cannon is by no means beyond reach. When functioning well, Cannon is an exemplary revolutionary — but beset by terrible personal crises and sometimes debilitating flaws. (Left-wing novelist James T. Farrell, in what is considered to be a literary reference to Cannon, sardonically quipped that he would have been “the Lenin of America if he hadn’t drunk whiskey.”)

Yet we can also see continuing efforts to be the best he could be and to work with others in fighting effectively for a better world. This may draw some not initially so inclined into appreciative engagement with this book and Palmer’s first volume, James P. Cannon and the Origins of the American Revolutionary Left.

Palmer quotes the pioneering historian of U.S. Communism Theodore Draper, who distinguished Cannon from many other Communist leaders of his generation because he “wanted to remember” the ideals and commitments of the early movement. “This portion of his life still lives for him because he has not killed it within himself.”

Some of the young Communists who rallied around Cannon as he first advanced the views of Trotsky’s Left Opposition — Max Shachtman, Martin Abern, Albert Glotzer – were responding to such qualities.

“In the early period of the fight it seemed to me that Jim had now ‘arrived’,” Glotzer commented. “There grew up in the various sections of the groups in the country a real respect for him because he took this line and gave leadership to it during the early struggles. This awakening manifested itself at the May conference” that brought the Communist League of America into being.

Difficult Times

Such positive feelings quickly turned to exasperation as Cannon seemed, more often than not, missing in action precisely when the new movement so badly needed him, displaying traits of demoralization and withdrawal hardly befitting the revolutionary leader his young comrades had taken him to be.

A convergence of problems bore down on the 40-year-old revolutionary which his younger comrades could not fully comprehend. There was, of course, the brutal fact of being cut off from the relatively small but vibrant Communist movement that he had helped to build and lead from 1919 through the 1920s, and the sense of loss and failure that this inevitably entailed.

There was also the devastating personal economic impact of the Great Depression. This was felt more keenly because it interwove with difficulties and responsibilities from an earlier marriage, including children who were emotionally and economically dependent on him.

His life partner Rose Karsner — a dedicated revolutionary activist in her own right — suffered a mental breakdown in this period. Overwhelmed, he took to drink. “Cannon’s bouts with the bottle also fueled resentments, if only because they contributed to his abstentionism,” Palmer notes. He elaborates:

“Cannon’s counterparts, most emphatically Max Shachtman, sustained the Left Opposition during their mentor’s personal retreat, but they lacked both compassion and understanding of Cannon’s situation. They clung tenaciously, if sadly, to a resentful and ultimately vindictive dismissal of Cannon’s appropriateness as the League’s leader, even as a vital contributor to a collective leadership. Unable to separate personal grievance from political criticism, and prone to cultivate the factionalism of cliques and personal sociability networks, Shachtman and others came to be blinded by their arrogance. A certain learnedness around questions of theoretical and international issues cultivated in them a sense of superiority over Cannon.”

Some continued to rally to Cannon, and a split seemed immanent in 1932-33. In the factional atmosphere, Palmer argues, Shachtman and the others tended to forget “what had attracted them to Cannon in their days in the Workers (Communist) Party: His undeniable abilities as a workers’ leader capable of appreciating and reading the pulse of American working-class militancy, intervening in class struggles to advance revolutionary politics, and extending the best that comrades had to offer, even as those talents sometimes reached past his own in specific areas.”

Even from afar, Trotsky was able to perceive the strengths of both Cannon and Shachtman, as well as their underlying shared commitment to Bolshevik-Leninist principles. He threw his considerable authority on the scales of unity, powerfully facilitating the decision of Cannon and Shachtman to work together, effectively and fruitfully, from 1933 to 1940.

One looks forward to the projected final volume of this project, which will likely be as large as the first two, covering an incredible range of developments from 1938 to 1974. Throughout that period, Cannon remained true to his early revolutionary commitments, providing much of interest for consideration by young rebels of the twenty-first century.

Relevance for Today and Tomorrow

It’s worth asking why the study of a long-gone Leninist party-builder might find a readership among volatile layers of radicalizing youth. Half a century ago, sophisticated literary critic Philip Rahv wrote about the mass movement of young activists arising in the late 1960s:

“Historically we are living on volcanic ground. … And one’s disappointment with the experience of the New Left comes down precisely to this: that it has failed to crystallize from within itself a guiding organization – one need not be afraid of naming it a centralized and disciplined party, for so far no one has ever invented a substitute for such a party – capable of engaging in daily and even pedestrian practical activity while keeping itself sufficiently alert on the ideological plane so as not to miss its historical opportunity when and if it arises.” (See Philip Rahv, Essays on Literature and Politics, 1932-1972, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1972, 353.)

As young Communists in 1934, Rahv and William Phillips had been editors of Partisan Review; influenced by Trotsky’s critique of Stalinism, they relaunched it as an independent and influential cultural publication in 1937. It became increasingly de-radicalized by the 1950s, but in the 1960s Rahv himself swung leftward before his untimely death, helping start a new journal, Modern Occasions.

Increasingly volcanic decades of the 21st century have led to ongoing radicalization, generating mass struggles of young activists. At first, the dominant left-wing influence was that of anarchism. Yet accumulating disappointments convinced many that something more was needed.

There was a massive popular response to the openly socialist appeals of Bernie Sanders’ Presidential campaigns, at the same time putting considerable wind in the sails of the once tiny but suddenly huge Democratic Socialists of America (DSA).

Here too there have been accumulating disappointments. Sanders’ socialism adds up to the moderate welfare-state program associated with European Social Democracy, yet even this is compromised by his commitment to the pro-capitalist Democratic Party.

Similarly, DSA gives greater attention to campaigning for the election of Democrats than to mass struggles of social movements. Rahv’s appeal for “a centralized and disciplined party” of revolutionary action still resonates.

A late-in-life interview provided Cannon an opportunity to share thoughts revealing some of his own hard-won insights:

“A revolutionist’s spirit and attitude is not determined by the popular mood of the moment. We have a historical view and we don’t allow the movement to fade away when it runs into changed times, which can happen as we know from experience.”

He emphasized a key element in the struggle to create a society of the free and the equal:

“People must learn how to work together and think together so that the work and thought of each individual becomes a contribution to the whole.”

What was needed, he added, was not “one person who becomes a one-man leader but a group of people who combined their talents as well as their faults and make a collective leadership. That’s what we need everywhere.” (James P. Cannon, A Political Tribute,including five interviews from the last year of his life, New York: Pathfinder Press, 1974, 27, 18, 44)

Reflections on the Author

The work of Bryan Palmer — Professor Emeritus at Trent University in Ontario Canada — has, over the past five decades, influenced the fields of labor history, social history, discourse analysis, communist history, and Canadian history, as well as the theoretical frameworks surrounding all of these fields.

A recent volume of excellent essays assessing his remarkably wide-ranging work, titled Dissenting Traditions, is available online. (Sean Carleton, Red McCoy, and Julia Smith, eds. Dissenting Traditions: Essays on Bryan D. Palmer, Marxism, and History, Edmonton: Althabasca University and Canadian Committee on Labour History, 2021, from which all following quotes are taken.)

Relevant to this volume and to his other contributions is the apt point made in Dissenting Traditions by Chad Pearson:

“Palmer’s work is a refreshing alternative to much mainstream scholarship. It teaches us a great deal: the value of working-class combativity, the explanatory power of Marxism, the limitations of institutional liberalism and social democracy, and the impossibility of genuine emancipation under capitalism.”

Two of Canada’s outstanding labor-scholars — Sam Gindin and the late Leo Panitch — have hailed Palmer, despite certain disagreements, for his “commitment to developing historical materialism and the high quality of research and sophisticated writing that has underpinned his recovery of working-class history in all its richness and flaws.”

They add: “In this respect, Palmer’s concern as a historian to recover and analyze the cultures of resistance that working people have developed in the course of practicing class struggle from below is not only a remarkable achievement of scholarship but also retains great contemporary relevance.”

This recalls the approaches of two activist-scholars who have profoundly influenced Palmer — E.P. Thompson and Leon Trotsky.

This leads us to the comments of two of the most insightful and incisive British historians on Communism, John McIlroy and Alan Campbell, who deliciously comment that “Stalinism was as different from socialism as the hippopotamus from the giraffe.”

Commenting on the first volume of the biography we are considering here, they had this to say:

“Innovative employment of an eye-opening swathe of sources and deft analytical fusion of protagonists and context and circumstances rendered James P. Cannon and the Origins of the American Revolutionary Left, 1890-1928 an achievement as biography and history.”

They add: “It stands as a rebuke to those who dismiss history written from the revolutionary viewpoint of its subjects.” The book we are considering here is very much in that vein.

March-April 2023, ATC 223