Against the Current, No. 223, March/April 2023

-

Women's Rights, Human Rights

— The Editors -

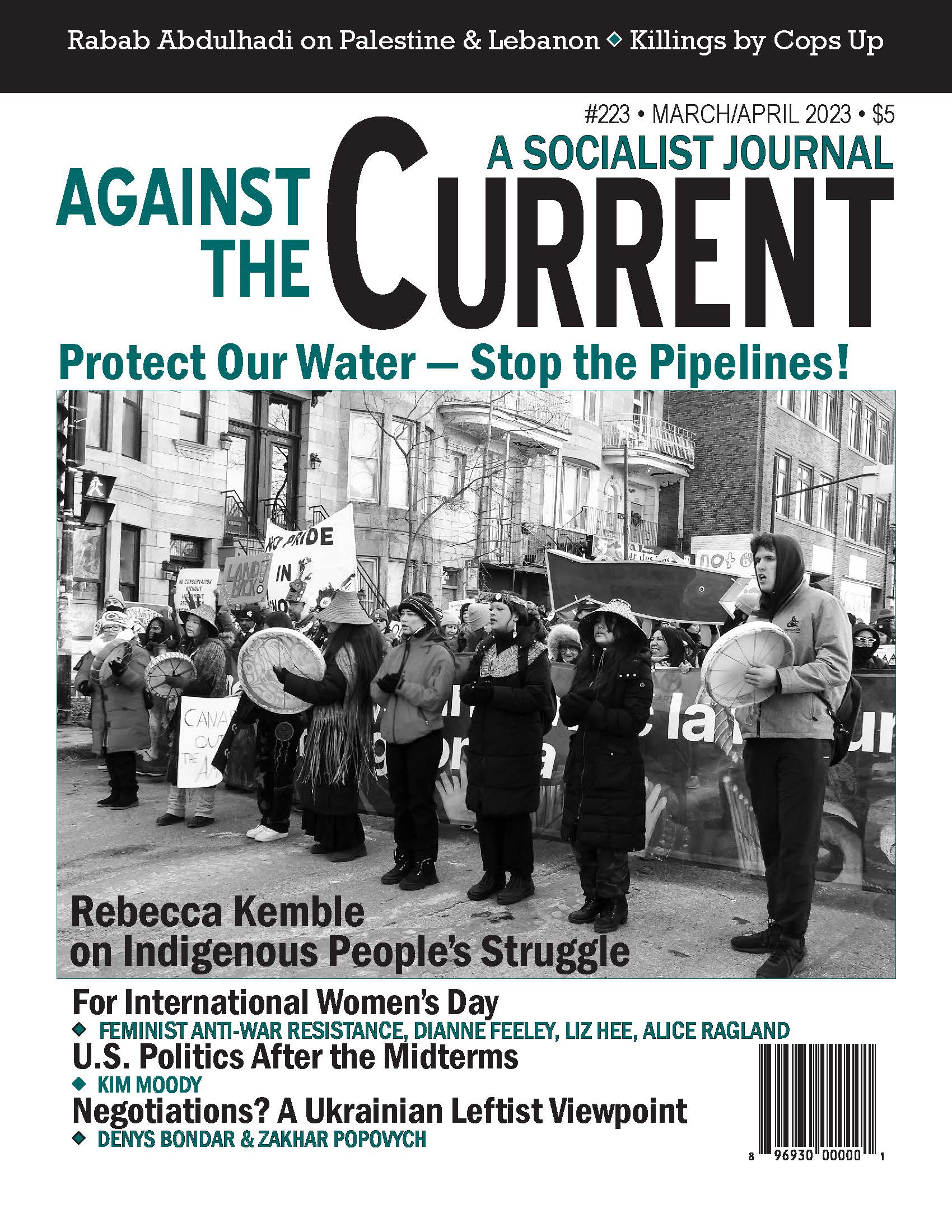

Lives Yes, Pipelines No!

— Rebecca Kemble - Salvadoran Water Defenders

-

Killings by Police Rose in 2022

— Malik Miah -

View from the Ukrainian Left

— Denys Bondar and Zakhar Popovych -

Witness, Resilience, Accountability

— interview with Rabab Abdulhadi - Palestine Solidarity Activism Under Fire

- The Horror in Occupied Palestine

-

Nicaraguan Political Prisoners Freed, Deported

— Dianne Feeley and David Finkel -

Stuck in the Mud, Sinking to the Right: 2022 Midterm Elections

— Kim Moody -

Heading for the Ditch?

— David Finkel -

Paths to Rediscovering Universities

— Harvey J. Graff - International Women's Day, 2023

-

Demanding Abortion Rights in Russia

— Feminist Anti-War Resistance/ FAS (Russia) -

Before & After Roe: Scary Times, Then & Now

— Dianne Feeley -

Abolition. Feminism. Now.

— Alice Ragland -

#Adoption Is Trauma AND Violence

— Liz Hee - Reviews

-

Radical Memory and Mike Davis' Final Work

— Alexander Billet -

A Revolutionary's Story

— Folko Mueller -

James P. Cannon, Life and Legacy

— Paul Le Blanc -

The World of Professional Boxing

— John Woodford -

A Powerful Legacy of Struggle

— Jake Ehrlich -

War and an Irish Town

— Joan McKiernan - In Memoriam

-

Mike Rubin 1944-2022

— Jack Gerson

Folko Mueller

In the Radical Camp

A Political Autobiography 1890-1921

By Paul Frölich

Haymarket Books, 2021, 270 pages, $30 paperback.

I WOULD ASSUME that most readers, if you are familiar with the author’s name at all, know Paul Frölich as the author of a Rosa Luxemburg biography. His most famous publication by far, it is a wonderful and very personal account of Rosa that has certainly withstood the test of time.

I first read that book as a young man in Germany, still trying to find my true political home. I knew little else about Paul Frölich, other than what appeared in the liner notes of the Luxemburg biography — that he was a founding member of the German CP (KPD) and later of the Communist International (Comintern).

This memoir will fill in many blanks, in particular regarding his early years and first political involvement. However, anybody hoping to learn more about Frölich’s more mature years within the Party, the factional struggles of the early to mid-1920s and his Comintern years, may be disappointed. The book ends with a chapter on the März Aktion or March Action of 1921, the mistimed communist uprising that ended up being a significant setback for the Party and the workers’ movement in general.

The editor, Reiner Tosstorf, himself well known in German leftist and academic circles for his numerous essays on the Spanish Civil War and particularly the POUM, mentions that the period from mid-1921 to mid-1924 was originally supposed to form the final part of Frölich’s memoirs.

Apparently, it was also planned to highlight the effects of the internal struggle ensuing in the USSR in 1923 on the international communist movement. Unfortunately, this was never realized. As Tosstorff points out in his excellent introduction, we don’t really know why Frölich ended his autobiography where he did.

Nonetheless, this is still a most valuable historical document: an eyewitness account from a leading Communist Party member who lived through an important and volatile epoch in Germany. He went through the whole left odyssey from a Social Democratic upbringing to joining the Internationale Kommunisten Deutschlands (IKD — via the Bremer Linksradikalen), to KPD (via the Spartacus League) to expulsion and joining the newly founded KPO (Communist Party — Opposition) to founding the SAP (Socialist Workers Party).

The impulse for writing the autobiography came from the International Institute of Social History which, shortly after it was founded in 1935, contacted well-known former Communist party members in different countries to submit essay-length memoirs. The idea was to document reports of actual events and internal party affairs that were either suppressed or falsified by the official Stalinist machine.

In the turmoil of the World War II years, all copies of Frölich’s manuscript were lost or forgotten. While the IISH founder and director, Nicolaas Posthumus was able to move the most valuable archives to London before the pending German invasion of the Netherlands in 1940, the remainder ended up in Nazi Germany.

Frölich himself was forced to flee from his exile in France, where he wrote the manuscript, to the United States where he lived as an émigré for a decade from 1941 on. His own copy was lost and it was only in 2007 that the IISH rediscovered their manuscript.

Childhood and Political Formation

Frölich’s political memoirs start with his childhood in Leipzig where he was born on August 7, 1884. Leipzig is located in Saxony, which was the most highly industrialized area of Germany at the time. The city grew from about 150,000 inhabitants at the time of Frölich’s birth to 500,000 inhabitants at the turn of the century.

With a growing working class, Leipzig developed into somewhat of a stronghold for the young Social Democratic Party. It struck roots in Protestant areas such as Saxony, as opposed to highly industrialized Rhineland or Upper Silesia where workers were more likely to follow bourgeois parties with strong Catholic ties, such as the Zentrumspartei.(1)

Frölich’s parents were heavily involved in party work, so much so that all their “daily affairs at home turned around the party.” His father, like so many of his social-democratic comrades of the time, was an autodidact, and managed to become a middle-rank party official heading up the Leipzig East district of about 500 members. His mother was active in the “trade association” before she started having 11 children but stayed active with internal party affairs.

As a child Paul was involved in underground party activities such as illegal leafleting, which invoked in him “a romantic magic of conspiracy.” Around the turn of the century, Frölich joined the workers’ movement in his own right. He became a member of the Leipziger Arbeiterverein, the local workers’ association.

While having the appearance of a strictly educational organization, it was in reality “a thinly disguised school of political struggle…and the most vigorous battles over party theory and tactics were conducted.” Frölich paints an intimate picture of the debates between Lasalleans and Marxist as well as the struggle against reformism in general.

During this time, Frölich also came in touch with Russian emigrees and socialist students and learned about the 1905 Russian revolution. In 1908 he joined the Leipziger Volkszeitung, a party organ, as a journalist apprentice, where he first met Karl Radek.

Another fascinating detail of the Leipzig chapter of his memoirs is his description of the “Corpora,” a secret organization within the SPD which was a legacy of the illegality of the anti-socialist law days.

Frölich describes it as “the real party machine. All questions that arose within the Leipzig workers’ movement were dealt with here, and for the most part decided without contradiction. Naturally party questions above all.”

Frölich tried to democratize the secret organization by suggesting the replacement of the old guard with an elected membership but found fierce opposition. This ultimately motivated him to move to Hamburg.

Hamburg and Bremen Years

Frölich arrived in Hamburg in October 1910 and continued his profession as a journalist for the local party paper, Hamburger Echo. While he enjoyed reporting on the struggles in its Altona district, where dock and industrial workers were concentrated, Frölich saw the petty-bourgeois nature of both the editorial staff at the Echo and party employees. Not surprisingly, almost all of them ended up in the social-patriot camp after the outbreak of World War I.

As a young reporter, Frölich came increasingly into friction with his editor. Unwilling to report on routine municipal news, he wanted to reveal the dreadful housing conditions in the poor districts.

When invited to join the editorial team of the Bremer Bürgerzeitung, he did not hesitate. At first enjoying the greater journalistic independence and political freedom he had as an editor working at a paper with a radical line closer to his own, he soon encountered deep factional battles. Frölich came to count on the backing of radical leftists including Karl Radek, Anton Pannekoek and Johann Knief, a former teacher and musician in charge of music criticism for the paper, who would become his best friend.

Yet Frölich was “completely unprepared” for the unanimous support of the war loan vote of August 4, 1914 by the entire SPD Reichstag group. He was unable to find an explanation for this “incomprehensible renunciation” by the SPD deputies. It was only when he received a letter from Radek that he learned about the internal discussions leading to this disaster.

Radek wanted Frölich and Knief to lauch a struggle against the official party line but it was too late. Both were called up during the very first week of war. Immediately engaged in propaganda activity, Frölich was discharged as permanently unfit the following year. He was called back up in 1916 as a clerk, for the “paper war” as he called it.

During this time Frölich was able to attend the Kiental conference, sometimes also referred to as the Second Zimmerwald Conference. This was a meeting of antiwar socialist groups and individuals similar to the original conference of the previous year. Here Frölich got to know Lenin, initially forming a not so favorable impression of him.

November 1918 and Aftermath

During the revolutionary events of 1918, Frölich was in Hamburg. The main leaders of the Hamburg left were a rather interesting pair, Heinrich Laufenberg and Fritz Wolffheim. Both could be considered council communists with certain anarchist leanings. But after the founding of the German Communist Party (KPD), the two were expelled. They moved on to become founding members of the ultra-leftwing KAPD (Communist Workers’ Party of Germany).(2)

Frölich dedicates an entire chapter to this forced split in the still young KPD, a split he had tried hard to prevent.

While Frölich’s recollections of the revolutionary period are confined to his experience in Hamburg, some of the general conditions as well as the composition of the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council were not unlike those in other large German cities.

Hamburg’s local Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council, for example, consisted of 15 workers and 15 soldiers, plus three representatives each of from the SPD, USPD (independent Social-Democrats), Left Radicals (predecessor of the Communist Party) and trade-union federation. This body of 42 people was the governing body of greater Hamburg and according to Frölich exercised “de facto dictatorial power.”

Like in most cities across Germany, the council reign in Hamburg ended on January 20th, 1919.(3) This came one day after the general national election for parliament, which was in turn triggered by the defeat of the misnamed Spartacus Uprising or January Battles.(4)

Just two days after the Bavarian soviet republic was established, Frölich arrived in Munich. However it seems to have been doomed from the start:

1) The SPD, who initially made a declaration in favor of the soviet republic, almost immediately betrayed the USPD and CP by either not participating or worse, trying to launch counterrevolutionary attacks from an old remnant government position in the town of Bamberg.

2) The soviet republic had no organ of real power. The police force was under counter-revolutionary control and had not been abolished. Not enough workers were armed, apart from a couple of CP-controlled factories.

In the end a massive offensive by the Freikorps (Republican militias) put an end to the republic in May of 1919. Almost all of the leaders were killed, as well as around 600 additional revolutionaries and civilians.

The fact that many leaders were of Jewish origin, such as Ernst Toller, Erich Mühsam, Gustav Landauer, Eugen Leviné and Tobias Akselrod, was used by the rightwing militias to sow antisemitic propaganda, ploughing fields that fascists would harvest soon after.

Frölich openly admited his mistakes, writing:

“At that time I had tactical ideas for which the description ‘ultra-left’ that has since been applied is not correct, yet that were too radical and showed a lack of real judgement of the conditions of the struggle. I was the representative of the left current.”

Kapp and March Action 1921

The last couple of chapters of Frölich’s memoirs deal with one episode that highlights the enormous strength of the German working class, while the another resulted in resounding defeat.

The first was the Kapp Putsch, an attempted coup against the Weimar Republic coalition government by ultra-reactionary forces on March 13, 1920. The coup failed within four days, because the unions’ call across the spectrum from SPD to KPD workers for a general strike.

Twelve million workers answered the call, paralyzing the country. At the time of the putsch, Frölich was in Frankfurt. He describes how the workers spontaneously took over the city even before the general strike was called. The police were too scared to come out of their barracks, commenting “There were no members of our party involved. There were no military leaders.”

But this victory led to strategic miscalculation in the March Action of 1921. The error arose partially out of an exaggerated sense of power that came from defeating the putschists and reinforced by the unification of the left USPD and KPD, resulting in a Unified Communist Party (VKPD) of some 400,000 members.(5)

Aware of the distress their Russian comrades were under — and under Comintern pressure — the party leadership felt ready to go on the offensive. They called a general strike and armed skirmishes broke out in different parts of the country. But the uprising was crushed by the German army (Reichswehr) and militia units. Frölich admits that he, together with the rest of the leadership, misjudged the situation entirely. He writes:

“(W)e overestimated the tensions, did not see the inhibiting factors, and particularly failed to recognize the possibility of a compromise in foreign policy…. I myself favored an offensive policy from the start… I failed to recognize as a general strategic lesson the necessity of a retreat or escape in a dangerous situation; this would only be brought home to me under to me under the pressure of very harsh facts…”

Learning from History

Frölich’s political memoirs should not only be of interest to scholars of German political history of the beginning of the 20th century but revolutionary socialists in general. While some basic knowledge of Germany’s political landscape and its different parties and groups at the time certainly helps, it is nonetheless an extremely accessible book with an almost anecdotal style.

We can count ourselves lucky that this interesting historical document, written by a key protagonist, has been recovered and published in English. If we do not want history to repeat itself, we should learn from it in order to prevent making similar strategic mistakes.

There is no self-aggrandizement here, no whitewashing or alteration of historical events. Unlike “official” anecdotes by CP members from that time, the book has not been subject to the Stalinist treatment of falsification or any cult of personality.

It is a very open and honest account with a fair amount of self-critique. Frölich finds plenty at fault in his and other leading members’ stands and actions around the Munich Soviet and March Action, for example.

The ending feels a little abrupt, no doubt because it was still a draft and he intended to write well beyond the events of 1921. While at times overzealous in his approach, Frölich was a genuine and unwavering fighter for the cause of the German working class.

Not a mere history book, this political autobiography is a torch passed on to us. It is up to us not to let this passion for revolution be extinguished.

Notes:

- Frölich does mention that in Leipzig the “Deutschkatholiken” a German-Catholic sect not to be confused with the Catholic Church proper played quite an important role in the local workers’ movement. This is, however, due to the fact that it was Catholic in name only and in actuality a freethinking organization founded by Robert Blum, the German democratic politician and revolutionary who actively participated in the “Märzrevolution,” the uprising of 1848.

back to text - The KAPD (Communist Workers’ Party of Germany) was an ultra-left split off from the mainstream CP, founded April 1920 in Heidelberg. The party soon splintered further, with individual remnants surviving until 1933, when the Nazis wiped them out. Frölich lamented this split from the KPD and dedicated a chapter to it in his book.

back to text - One notable exception is the Munich Council Republic which also grew out of the November uprisings but was not declared until April 7th, 1919.

back to text - The Spartacus Uprising was neither initiated by the Spartacist Group nor the Communist Party, but was triggered either spontaneously or through an agent provocateur. It consisted of a general strike and armed struggle in Berlin (January 5th through January 12th of 1919). The build-up that sparked these events was the dismissal of the Berlin Police President Emil Eichhorn, a member of the Independent Social Democrats (USPD), by the Council of People’s Representatives led by Friedrich Ebert on January 4, 1919. Eichhorn had been appointed by the first Council of People’s Representatives. This formed part of an overall strategy by Ebert to successively replace USPD members by MSPD (majority SPD) members. This resulted in the USPD no longer regarding it as a legitimate interim government. The underlying cause was the conflicting political aims of the groups involved in the November Revolution. The MSPD leadership around Ebert, Scheidemann and Noske aimed for a rapid return to “orderly conditions” via the elections to the National Assembly. The USPD, parts of labor, and the Revolutionary Representatives as well as the KPD wanted the continuation and safeguarding of their revolutionary goals (socialization, disempowerment of the military, dictatorship of the proletariat). They interpreted Eichhorn’s dismissal as an attack on the revolution.

back to text - The right-wing of the USPD dissolved itself back again into the SPD (majority Social Democrats).

back to text

Further Reading:

There are a number of books and biographies covering the events Frölich witnessed. I will focus here only on the ones that are either written in English or have been translated (at least in an abridged version).

For further reading on the period of Frölich’s childhood and political formation, I recommend August Bebel’s memoirs Aus meinem Leben. I believe the full text was translated and available in different tomes in English at some stage, but most are now only available as used. However, there is a recent edition of the first part put out by Franklin Press as Bebel’s Reminiscences.

An invaluable resource in English regarding the emerging split between reformists and revolutionaries within the SPD around the time of WW I is Carl E. Schorske’s German Social Democracy 1905-1917: The Development of the Great Schism. Sebastian Haffner’s Failure of a Revolution: Germany 1918-1919, is a brilliant account of the treacherous counterrevolutionary actions by the social democrats in power at the time. The original German title is more aptly called Treason.

For a deep dive into this important period in German and world history, I highly recommend Pierre Broué’s tour de force, The German Revolution, 1917-1923.

For further reading on the Zimmerwald (and Kiental) conferences, War on War by R. Craig Nation and published by Haymarket Books is a solid resource in English.

Several protagonists of the Munich soviet have written memoirs. One autobiography is Ernst Toller’s Eine Jugend in Deutschland, somewhat awkwardly translated into I was a German, available from Kessinger Publishing. Toller, of course, briefly headed up the first (non-CP-dominated) Munich soviet republic; one entire chapter is dedicated to that experience.

Victor Serge’s dispatches from Germany on behalf of Comintern’s Inprekorr, collected under the title Witness to the German Revolution and published by Haymarket Books are also well worth a read. They cover the year 1923, which was the last year of revolutionary upheaval in Germany.

March-April 2023, ATC 223