Against the Current, No. 223, March/April 2023

-

Women's Rights, Human Rights

— The Editors -

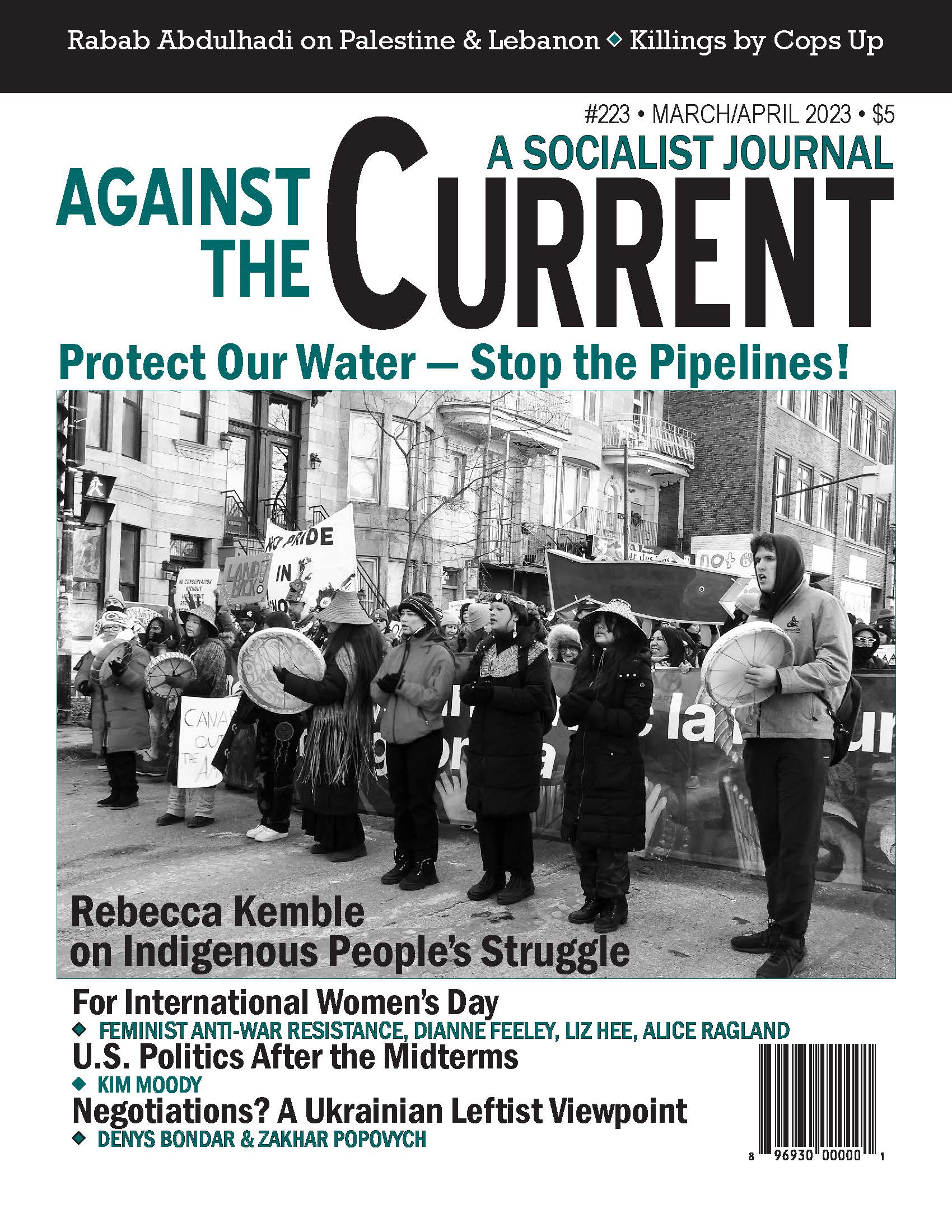

Lives Yes, Pipelines No!

— Rebecca Kemble - Salvadoran Water Defenders

-

Killings by Police Rose in 2022

— Malik Miah -

View from the Ukrainian Left

— Denys Bondar and Zakhar Popovych -

Witness, Resilience, Accountability

— interview with Rabab Abdulhadi - Palestine Solidarity Activism Under Fire

- The Horror in Occupied Palestine

-

Nicaraguan Political Prisoners Freed, Deported

— Dianne Feeley and David Finkel -

Stuck in the Mud, Sinking to the Right: 2022 Midterm Elections

— Kim Moody -

Heading for the Ditch?

— David Finkel -

Paths to Rediscovering Universities

— Harvey J. Graff - International Women's Day, 2023

-

Demanding Abortion Rights in Russia

— Feminist Anti-War Resistance/ FAS (Russia) -

Before & After Roe: Scary Times, Then & Now

— Dianne Feeley -

Abolition. Feminism. Now.

— Alice Ragland -

#Adoption Is Trauma AND Violence

— Liz Hee - Reviews

-

Radical Memory and Mike Davis' Final Work

— Alexander Billet -

A Revolutionary's Story

— Folko Mueller -

James P. Cannon, Life and Legacy

— Paul Le Blanc -

The World of Professional Boxing

— John Woodford -

A Powerful Legacy of Struggle

— Jake Ehrlich -

War and an Irish Town

— Joan McKiernan - In Memoriam

-

Mike Rubin 1944-2022

— Jack Gerson

Jake Ehrlich

“Revolutionaries, resistance fighters and firebrands. The radical Jewish tradition.”

By Janey Stone.

AMONG PROGRESSIVE JEWS in the United States, there is something of a reawakening of historical memory.

In 2014 Rachel Cohen maligned “The Erasure of the Jewish-American Left” in a Medium article of the same name, stating for example, “While most Jews today know The Jewish Daily Forward used to be published in Yiddish — many are unaware that it was a self-proclaimed leftist paper, proudly backing the Socialist Party for thirty-five years.”

Today, however, it is common for progressive Jewish organizations with considerable bases — like Jews For Racial & Economic Justice in New York or Bend The Arc nationally — to invoke broad-stroke histories of Jewish activism, from the American labor movement, to the Civil Rights Movement and the New Left.

Many are familiar at least in passing with Emma Goldman and her quip about dancing in the revolution. They might know a thing or two about the Yiddish-speaking political formation known as the Jewish Labor Bund, which rejected the colonial state-building aspirations of Zionism, but sought to maintain Jewish cultural particularity rather than assimilate into transnational communism.

As progressive Jews come to increasing involvement in the work of racial justice, immigrant rights, prison abolition, labor organizing and other causes, it’s natural that such histories of Jewish activism surface.

And as the unjust and violent occupation of Palestine by the Israeli state continues, it’s understandable — and commendable — that activists search for models to inform the development of their non-/anti-Zionist political identity.

This history, however, is not commonly referenced with much specificity. Here’s where Janey Stone’s treatise Revolutionaries, resistance fighters and firebrands: The radical Jewish tradition provides granularity, detail and first-hand accounts to a broad cross section of Jewish working-class activist history. It’s a supplement published by the Australia-based Marxist Left Review affiliated with Socialist Alternative (AU) [not related to the U.S. group of the same name — ed.]

The text challenges Zionist historiography of Jewish passivity in the face of persecution, but its significance extends beyond that — more than just a scholarly corrective, it’s a political intervention.

In Revolutionaries, Jewish radicals today are equipped with an understanding of history that will strengthen their — our — efforts to build a mass radical Jewish culture outside of the extant communal infrastructure, which is controlled in large part by philanthropists, federations and other bourgeois forces.

Stone’s intent is to craft an activist counter-narrative to mainstream approaches to Jewish history. She rejects both the “lachrymose conception of Jewish history” that sees Jews as victims of superstition and relentless persecution, and the subsequent Zionist narrative that promotes separatist colonial nationalism as the viable response.

Historical Memory and Meaning

The book has predecessors, but this slim volume’s assembly of diverse sources is worthwhile. Stone’s account spans time and space from the Russian Empire to Britain and the United States, from around the 1880s and culminating in the eve of World War II in 1939.

What I found particularly commendable is her focus on not just the grand and pivotal moments of Jewish activism (e.g. the 1902 Kosher Meat Boycott, or the 1909 “Uprising of the 20,000” general strike in New York, or the heroic anti-Nazi resistance in Warsaw), but the fits and starts that characterize everyday struggle.

We learn of strike efforts that fail more often than they succeed; demonstrations whose number of attendees may seem paltry to us; campaigns that falter. It’s actually these accounts that I feel are so essential for activists of today to read, when our social movements and leftist organizations face all-too-familiar fits and starts of energy and stagnation.

As tempting as it is to think of our current situation — either as a historic boiling point, or a (pre)revolutionary moment — we may be better served to adopt a more tempered view of struggle — seeing ourselves not necessarily as ushers of an approaching denouement, but instead as nodes along a winding, gnarled chain of activism.

The journey passes through wildcat strikes in Bialystok, the Bund’s role in organizing the first congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party, the formation of the United Hebrew Trades in America in response to the nativism of the American Federation of Labor, and beyond.

Some of this, to be sure, is the story of a Jewish working-class movement whose base was ultimately destroyed by Nazism and Stalinism. Yet the cultivation of such a view of history, seeing ourselves as inheritors of “the radical Jewish tradition” can be inspiring and necessary, especially in times of morass.

In cataloging Jewish resistance to various forms of exploitation and domination, Revolutionaries seeks not only to provide historical corrective — to stress the self-determination of Jewish subjects as agents, not mere victims — but to challenge the Zionist exaltation of insularity and ethnocentrism over intergroup cooperation and solidarity. Stone writes:

“All Zionists treat Jews, to some degree, as a single body, distinct and separate from non-Jews. A major theme of this study is how class divisions within the Jewish community meant that workers had very different interests from those of their Jewish bosses; solidarity between Jews and non-Jews contributed to success in working-class struggles, including the fight against anti-Semitism.

“Theodor Herzl, the founder of Zionism, argued that anti-Semitism was inherent in non-Jews and could not be fought. By contrast, the socialist response to anti-Semitism was that it could be fought, along with other forms of oppression and racism, and that the struggle of the working class to overthrow capitalism brought with it the best possibility of creating an equal society. This combination of class struggle, solidarity, socialism and the fight against oppression is the story of the radical Jewish tradition.” [Introduction, between notes 11-12]

Mythology of Unity

That Jews do not constitute a homogeneous mass should be obvious, but this false idea continues through this day, with representatives of the State of Israel and major Jewish communal organizations claiming to act in the interests of “the Jewish community,” as if such a singular entity exists. References to an imagined unity elide material differences of wealth, class, intra-Jewish identities (histories of discrimination against “Ostjuden,” the Jews of Eastern Europe, by Central and Western European Jews; against Mizrachim and Sephardim by Ashkenazim; against Jews of Color by white Jews, etc.), conflicting political commitments, and more.

The construction of a singular “us” against all of “them” has been deployed to tamp down and delegitimize internal conflict, as Stone notes was the case in pre-revolutionary Russia:

“In small workshops, both the bosses and the workforce were Jewish, and this had been the basis for a particularly insidious form of super-exploitation — it was easy to appeal to the belief in a common interest when everyone attended the same synagogue and lived and worked apart from the non-Jews in separate Jewish quarters of the towns.” [Note 20]

She goes on to note, citing the scholar Ezra Mendelsohn, that in contexts where Jews and non-Jews worked together for Jewish factory owners, the bosses deliberately sought to fuel tensions between Jews and Christians to stymie worker organizing:

“A Jewish factory owner in Bialystok ‘used all his eloquence to arouse a strong hatred on the part of the Christians for the Jews’ to prevent them joining together in a strike, while, in ?ód?, a boss in a sock-making shop ‘instigated the Christians against the Jews and fomented quarrels between them one factory owner argued: “we must hire people, especially Christians, who will be able to give a good lesson to those strikers rising against their employers.””’ [Notes 55-56]

The appeal to cooperative unity and the active foment of its opposite go hand in hand, as will be familiar to today’s workers in corporations and non-profit organizations alike, where the bosses remark that “we are all family,” while consulting with union-busting firms and preparing to recruit scabs.

For Zionists, whose political aspirations are essentially realized with the establishment of Jewish statehood, there is no need to resolve or transcend such tensions between Jews and non-Jews. It is not only convenient but strategic to exacerbate them, as the Jewish bosses described above and the early architects of Zionism like Herzl well understood.

For those of us whose ideal of a better world involves something other than an ethnostate, however, it is imperative to articulate alternatives. Rather than appealing to the inevitably-conservatizing notion of “Jewish unity,” we ought to echo those Jewish socialist forebears who, as Stone notes,

“…[tried] to replace the tradition that all Jews were brothers with the new idea of class solidarity. They argued that ‘Among us workers there exists no difference between a Jew and a Christian, we advance hand in hand against our oppressors’ and the wealthy Jews ‘have their own God; their money, their capital, is their god,’ whereas ‘our God [of the workers] is [class] unity.’” [Note 58]

“Polarization” is much maligned in today’s mainstream liberal discourses within and beyond Jewish communities, but we need only to turn to this history to see its strategic value.

Power of Solidarity

A noteworthy aspect of this history is its numerous accounts of solidarity between Jews and non-Jews. These are not always neat and tidy — such as when starving Jewish immigrant strikers on London’s East End received a donation of £100 from dockers participating in the Great Dock Strike of 1889, despite the antisemitism of docker leader Benjamin Tillet, who considered Jews “the dregs and scum of the continent.”

They nonetheless serve as potent inspiration for inter-community organizing. Rudolf Rocker, a non-Jewish German anarchist who spoke Yiddish and became a premier organizer in the East End in the early 20th-century, stands out.

In 1912, when the (non-Jewish) tailors of London’s West End went on strike, Rocker and his comrades urged at a mass meeting that the (Jewish) East Enders not just express statements of support, but go on strike as well. Eight thousand Jewish tailors enthusiastically agreed.

Supported with supplies from local Jewish bakeries and cigarette-makers, and funding from benefit performances held at Yiddish theaters, the strikers struck for about a month and won every demand they articulated, including — against all odds — the recognition of their union.

Energized by this victory, the Jewish workers mobilized to support an ongoing strike among the largely Irish Catholic dockworkers, contributing supplies and monetary donations and, famously, welcoming more than 300 dockers’ children into their homes for lodging and sustenance.

Years later, in the famed 1936 “Battle of Cable Street,” when Oswald Mosley attempted to march 3,000 of his British Union of Fascists through the East End and were met by some 100,000 antifascists (and 10,000 police officers, providing Mosley’s men protection), it was Irish dockers who served as the vanguard.

Stone quotes Max Levitas, a Jewish communist who had grown up in Dublin, who said:

“We knew the Irish would stand with us. When [the dockers] went out on strike in 1912, it was a terrible time. Jewish families took in hundreds of their children. They were starving. We knew [the Irish dockers] wouldn’t forget. They wanted to repay the debt.… There were huge crowds, the dockers were shouting: ‘Come on lads, we’re going to go out and stop them! They want to march, we won’t let them!’” [Note 278]

Stone’s work is filled with similar anecdotes that should be part of the toolbox of Jewish organizers and activists alongside our standard fare invocations of tikkun olam (the mandate to “repair the world”) and the social justice messages of the biblical Prophets.

We should know and transmit the story of how Eleanor Marx (daughter of Karl) experienced an increasing identification with her Jewish heritage (Karl’s parents had converted to a rationalist Lutheranism, though both of his grandfathers — Eleanor’s great-grandfathers — were rabbis).

Through working with the Jewish immigrants of London’s East End, Eleanor went so far as to proclaim “I am a Jewess” in response to the Dreyfus affair in 1894, and to march alongside the socialist “sweatshop poet” Morris Winchevsky, proclaiming to him that “We Jews must stick together.”

Though Rocker and E. Marx are examples of non-Jewish involvement in Jewish affairs, they prompt us to consider how we as contemporary Jewish activists may show up “as accomplices, not allies” (IndigenousAction zine) with similar solidarity in movements led by others.

Alternative Institutions

Relevant to Stone’s interest in counter- narrative is the fact that Jewish radicalism was tied to and supported by alternative institutions that nurtured a counter-culture. The Berner Street Club (1885-1892) and Jubilee Street Club (1906-1914) in London provided vital hubs for not just organizing, but education, arts and social life. About the latter, Stone writes:

“During strikes, it served as an organising centre but was also open at other times. It offered a bar (non-alcoholic) and food; dances, plays and concerts; chess competitions; and English lessons. Lectures on political and cultural topics, which were not restricted to Jewish themes or authors, opened the eyes of many workers to the wider world. Importantly, the club was open to all, Jewish and non-Jewish. It attracted the young… and old, the political and apolitical, the informed and ignorant.” [Note 151]

The “informed” in attendance sometimes included figures of renown: an account from a club volunteer describes the presence of a “small, intense man who sat alone” drinking Russian tea at Jubilee Street — Lenin.

Deliberately radical in orientation, these venues were sites where the workers’ movements could expand beyond economism, and engage in discussion and practice of alternative social mores, including gender egalitarianism, atheism, and “free love.” Such alternative institutions played an essential role in the proliferation of radical ideas among the working class, both Jewish and non-Jewish.

(A stellar contemporary example of such a project is Glasgow’s Di Roze Pave/Pink Peacock, a small “queer, yiddish, anarchist café & infoshop in glasgow’s southside,” whose fare is priced at “pay-what-you-can down to £0.”)

The contents of Revolutionaries should render it a lasting feature on the bookshelves of today’s Jewish left. But as Stone’s conclusion notes, “This is not a history of Jews, but a history of a section of the international working class that struggled for a better world on the basis of class and the fight against oppression.” [Conclusion, before note 395]

Indeed, I consider this recommended reading for activists of all stripes. Though there is a bit of “inside baseball” with detailed references to Jewish and socialist movement history, the prose is on the whole concrete and easily digestible, with compelling quotations throughout.

These are stories that need to be told. We must read and transmit them, as we play our part in carrying forth this “radical Jewish tradition,” from one generation to the next.

March-April 2023, ATC 223