Against the Current, No. 192, January/February 2018

-

Open and Hidden Horrors

— The Editors -

The #MeToo Revolution

— The Editors -

Black Nationalism, Black Solidarity

— Malik Miah -

Harvey's Toxic Aftermath in Houston

— Jennifer Wingard -

Florida Students Confront Spencer

— Aliya Miranda -

How the UAW Can Make It Right

— Asar Amen-Ra -

The Kurdish Crisis in Iraq and Syria

— Joseph Daher -

Kurds at a Glance

— Joseph Daher -

Clarion Alley Confronts a Lack of Concern

— Dawn Starin -

Catalunya: "Only the People Save the People"

— Bayla Ostrach -

Catalunya: Organizations at a Glance

— Bayla Ostrach -

Catalunya: Abbreviated Timeline

— Bayla Ostrach - Egyptian Activists Jailed

- On the 100th Anniversary of the Russian Revolution

-

The October Revolution: Its Necessity & Meaning

— David Mandel -

Theorizing the Soviet Bureaucracy

— Kevin Murphy - Reviewing Black History & Politics

-

Race and the Logic of Capital

— Alan Wald - Black History and Today's Struggle

-

Racial Terror & Totalitarianism

— Mary Helen Washington -

Portrait of an Icon

— Brad Duncan -

Lessons from James Baldwin

— John Woodford -

New Orleans' History of Struggle

— Derrick Morrison -

Claude McKay's Lost Novel

— Ted McTaggart - Reviews

-

Language for Resisting Oppression

— Robert K. Beshara - In Memoriam

-

Estar Baur (1920-2017)

— Dianne Feeley -

William ("Bill") Pelz

— Patrick M. Quinn and Eric Schuster

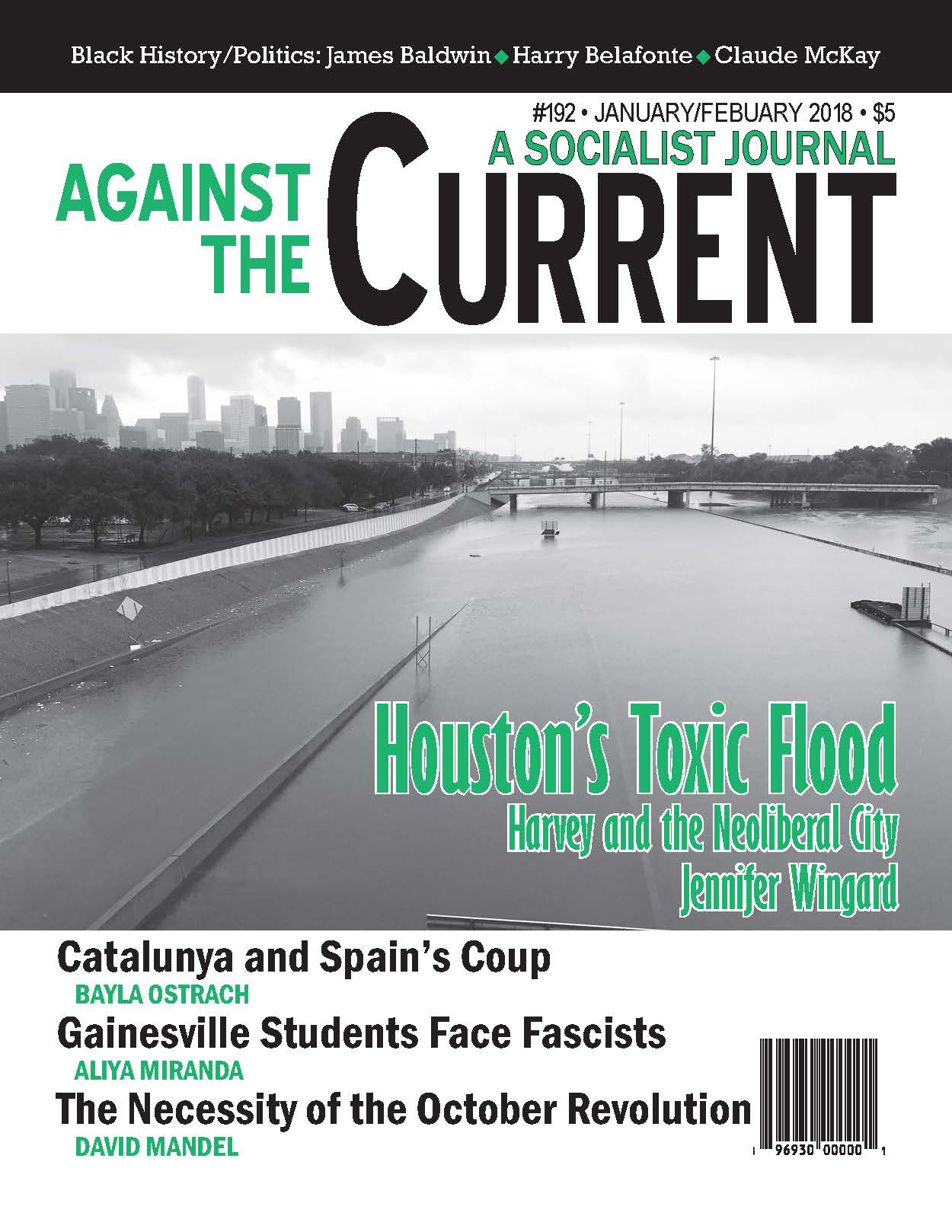

Jennifer Wingard

WAKING UP ON August 29, 2017, with news of failing levees and reservoirs in Houston, the city I’ve called home for the last ten years, was emotionally trying. Even though Hurricane Harvey was on track to end its constant deluge of rain on the Houston metro area and move east, there was a consensus that Houston, with its high density of petrochemical plants, was not yet out of the woods.

So on that day, the very anniversary of Hurricane Katrina — another devastating hurricane whose effects were felt for years after the event — Houston was quite clearly revealed as another example of the devastating results of neoliberal economics’ neglect on state municipalities and local governments.

As Harvey moved toward the east and lost its momentum, the city’s problems were just beginning. Due to Houston’s commitment to a “No Zoning” policy, several housing developments had been built in watersheds across the metro area, leaving significant flooding in scattered areas around the city. Water levels were going down but very slowly because at this point, levees, creeks, and tributaries were still at maximum capacity as water flowed out to the gulf.

Many articles have been written about Houston’s problems: lack of zoning, urban and suburban sprawl, poor city planning, and lack of attention to drainage. These are problems unique to Houston and have been blamed for the devastation. In many ways, Houston’s policy of No Zoning is one of its defining traits. And all these are deeply tied to Houston’s (and Texas’) low oversight, pro-business model of government.

This approach can lead to catastrophic events. (Remember the explosion in West, Texas a few years back, or even the Blue Bell Ice Cream listeria drama two summers ago.) So of course, these were factors in the flooding because they are factors that define the city of Houston — how it is run; how it is built; how it is lived. But I would challenge any U.S. city to take on 30-50″ of rain in four days (12 trillion gallons) and not have some levees break, reservoirs spill over, tributaries, creeks, and bayous top their banks.

I challenge any city’s infrastructure, no matter how sensible (I’m looking at you, “Smart Growth” plans), to withstand that kind of heavy, unrelenting rain.

The areas near the Addicks/Barker reservoirs (the two main levees designed to keep the city from flooding) were issued a mandatory evacuation notice for homes that had taken on water because it was projected the water would not recede for at least ten more days.

The flood water was toxic. Initial tests confirmed high levels of staph and e.coli, and later tests revealed raw sewage in the water. Further testing will be conducted to see if chemicals from the local petrochemical plants are in those waters too.

Part of the reason for these homes flooding was the overspill from both dams and the “controlled release” of water from both dams, which was done as a means to ensure they would not fail. Many neighborhoods that did not initially flood in Harvey flooded due to the overspill and release of water from the dams. These were for middle- and upper-middle-class Houstonians who bought homes in developments in watershed areas. It is not clear if they were apprised of this when they purchased their houses.

Chemical Spills and Explosions

In addition to the excess of water across the city, every petrochemical plant and most of the EPA superfund sites were breached during the flooding. One chemical plant in Crosby, a southeast suburb of Houston, had two unplanned explosions, and the advisory board of Arkema Inc. decided to explode the remaining six warehouses in order to control the damage.

The first responders to the Arkema chemical plant are suing the company because the plant was not forthright about what the responders would face, nor did they make sufficient prior preparations. The city of Crosby is also suing the Arkema chemical plant for negligence and prolonged sickness because of the toxins released by the blasts. The CEO of Arkema claimed the air from the explosions was “no more toxic than regular Houston air.”

Independent researchers and corporate reporting have confirmed that an estimated 4.6 million pounds of air polluting chemicals have been emitted from refineries and petrochemical plants around Houston and southeast Texas, and the area around Crosby shows an even higher distribution. People around Arkema have complained about burning eyes and sinuses since the first explosion at the factory.

Couple that with the orders across the city to boil water, and the additional tests showing that the mud from the receded flood waters contained signs of chemical seepage and infection. All of this demonstrates that Houston is a sick city post-Harvey, one that will not know the full ramifications for years.

Houston’s air, water and land are a mess of benzene, e.coli, staph, and sewage. And one of the largest Environmental Protection Agency Superfund Sites has leaked at least 70,000 nanograms per kilogram of dioxins. The EPA recommends toxic cleanup when 30 ng/kg are present in the environment.

Because the superfund site is located next to the San Jacinto River, a main tributary to the gulf, it is advised that Houstonians do not fish or eat fish, shrimp, or oysters from the gulf. Not only can dioxins live in the ground and ground water for years, but they can also taint whole populations of aquatic creatures, which will cripple Houston’s shrimping and fishing businesses. Harvey’s impact on the air, water and land, as well as the economy of Houston, will be felt for years to come.

In addition to the physical environmental cost, the animal cost post-Harvey was acutely felt as well. Houston’s local animal populations were severely impacted, but none more significantly than several of our native bat colonies. These colonies help to control the abundant mosquito population across Houston, and with the additional presence of standing water and lack of a full bat population, the post-Harvey mosquito count rose to astronomical numbers.

The military’s answer has been to spray the organophosphate insecticide Naled over six million acres of the Houston/SE Texas area to “assist” with the “control of local insect populations.” Naled has been banned in Europe because of its dangerous side effects, one of which is killing off local bee populations. Again, Houston is faced with the addition of new chemicals into our already toxic environmental soup.

The Self-Help Narrative

There is a lot being written about Texas Grit and #HoustonStrong, and how individuals and communities have come together to help during and after this massive storm. And that is true. It has been wonderful to see the collective civic action, the contacts and requests made via social media, and the organization of individuals to collect supplies and help those in need across the region.

All this focus on individual (citizen or business) efforts has eclipsed the coordinated effort from local and national government. The National Guard, FEMA, Army Corps of Engineers, police, fire and medical professionals from all over the United States, the EPA, and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) have all been on the scene since before Harvey made landfall.

But it is much more newsworthy in our present news cycle to watch and learn about everyday folks saving one another. It aligns with the need for us all to find hope and triumph of the spirit in times of disaster.

Again, I am by no means saying what these citizens did was not awesome, very much needed, and even a bit heroic, and it certainly does represent Texas grit. But the lack of visibility of national and local government also fits into a very “Texas” narrative — that of being the Lone Star state.

You see, Texas prides itself on not needing the Feds. Post-2008 recovery, then-Governor Rick Perry (now Secretary of Energy) very publicly refused aid for our compromised economy. What wasn’t deemed newsworthy was that the legislature overrode Perry’s injunction and took the aid just months later.

So it is not surprising that many folks did not know that the EPA or the CDC were actually onsite here in Houston and had been since the beginning of the storm. See, here in Texas we got grit, and we don’t need no stinkin’ Feds to help us in our time of need — unless we do, and then we keep it on the down low.

The Pending Crisis

With that said, I think it is criminal the lack of systemic action or reporting about the toxins leeching into Houston. Folks are wading, cutting and clearing out brush, furniture and building materials, all saturated with toxic sludge, doing their best to prevent mold and sewage from entering their remediated homes. But there are other threats no one is identifying or naming officially.

Unfortunately, this means that what the media and independent analysts find is often discounted, no matter how clear their information may be.

As a nurse whom I’ve known since I was a kid, Denise L. Unger, expressed: Houston is about to have a real public health crisis on its hands if they are not very, very careful with how they manage post-storm debris and containment. But it seems that is not the focus at this moment, so we all walk around with our eyes just a bit itchier than they were a few weeks ago and with a cough that creeps up here and there. No real sickness, yet.

Everything is getting back to normal, but nothing feels exactly the same. You cannot drive anywhere in Houston without seeing erosion, felled trees, dirt on the road, piles of “trash” from homes, or new cars denoted by temporary license plates. Everywhere there are markers of Harvey even after the waters have receded.

Yet folks are back at work and school. Grocery stores are stocked. Families are meeting up for Sunday dinners. Life moves forward, and even with rooms and walls or whole floors not livable, we all pay our bills and show up for our lives and for one another. It is a return to normal, but just slightly different.

Then there is the environment around us that has imperceptibly changed. Even those of us who are not outwardly ill (and have health insurance) are making sure our tetanus shots are current; we have eye drops; we spray on DEET liberally; we pop just a few more analgesics to quell our headaches; we listen to see if wheezing is accompanying the slight cough and irritated throat we have when we go outside.

If we could, we would avoid the piles of debris outside remediated homes and businesses because of the smell, but we cannot. They are all around us, much like the mosquitos.

Part of our new normal in Houston, I fear, will be dealing with these nagging health concerns. These minor irritations that seem like nothing more than severe allergies will become the stuff of small talk at parties. And in several years when the really serious effects of these chemical incursions are seen, only a few liberal news outlets will connect them to the post-Harvey chemical soup that was southeast Texas.

By then, Texas will have made more rollbacks to regulations to “stimulate business growth” and even more layoffs of governmental oversight agencies in the name of “offsetting the cost of rebuilding post-Harvey,” yet again begging the question: what are the “costs” we are willing to shoulder here in southeast Texas?

But I suppose the more pertinent question is who will shoulder the costs that will inevitably befall southeast Texas? Even now, barely three months after Harvey, as the FEMA payouts stall and the city’s skilled workforce is pushed to its limits, we are beginning to see that those who have the means are putting Harvey in their rear view, and those with limited funds are struggling to return to a “normal” life.

This division is not along racial lines, nor is it reserved for the working poor versus the professional classes. Instead, due to lack of state and national support both pre-and post-storm, only the Houstonians at the top of the economic food chain are able to rebuild and move forward quickly. Even professional, middle-class folks are still displaced, paying 121% higher prices for contractors and supplies.

Harvey may have hit the city of Houston “equally,” but its aftermath reveals the stark contrast between the have-and-have-nots across the city. And it is this same inequity that has been fostered by governmental pro-business economic policies both nationally and in Texas over the last three decades. The ramifications caused by Harvey demonstrate what can happen when businesses are left to their own devices in the name of profit.

January-February 2018, ATC 192