Against the Current, No. 187, March/April 2017

-

Trump's Road to Ruin

— The Editors -

Making Trump's America Ungovernable

— Malik Miah -

The Ohio Vote in November

— Kim Moody -

Sanders' Campaign & the Democratic Party

— Jules Greenstein -

Adorno's The Authoritarian Personality

— Christopher Vials -

A Partial Peace in Colombia

— Kevin Young -

Lessons from New Orleans

— Peter Brogan interviews Kristen Buras - Women in Struggle

-

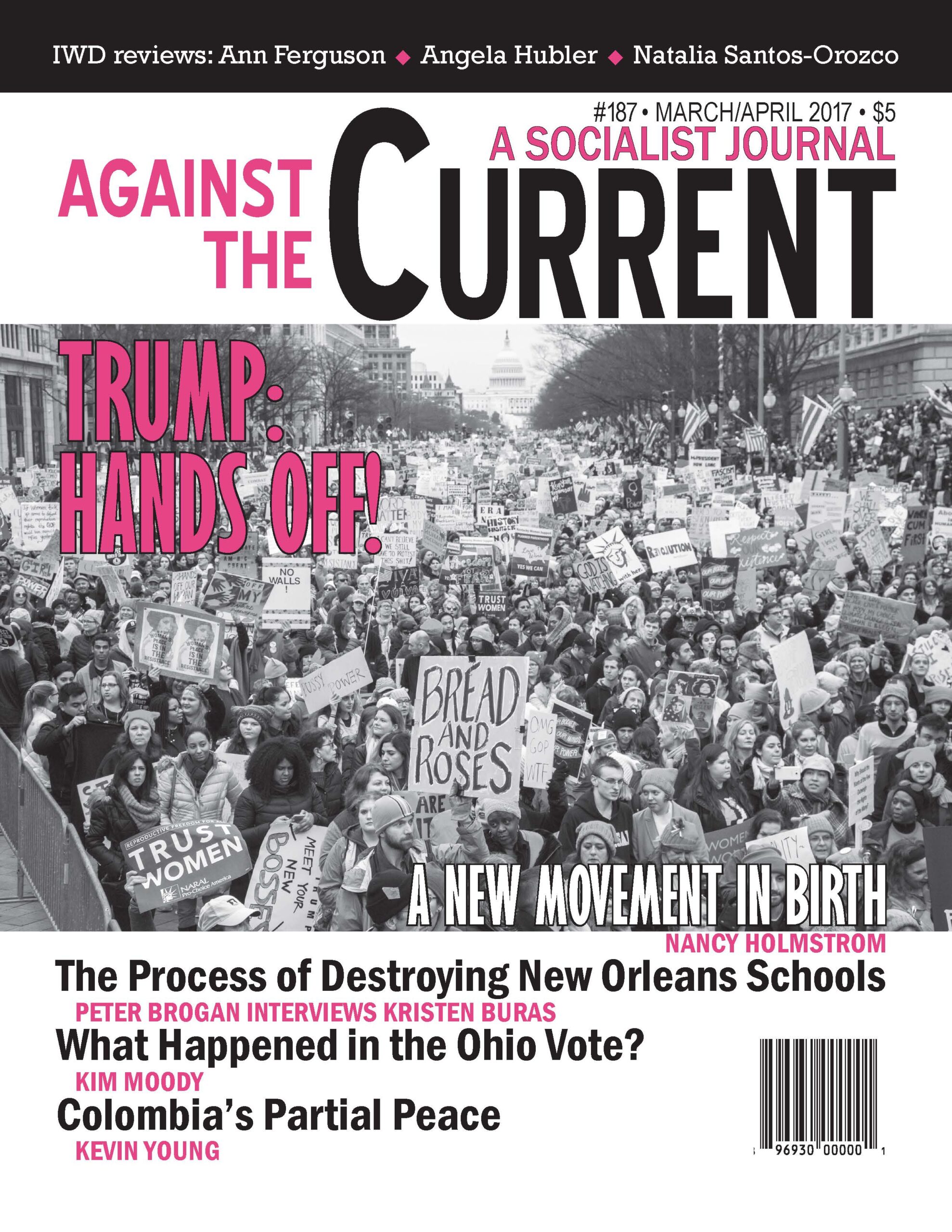

Birth of a New Movement

— Nancy Holmstrom -

The Journeys of Julia de Burgos

— Natalia Santos-Orozco -

Florynce Kennedy & Black Feminism

— Angela Hubler -

Marxist and Feminist Interventions

— Ann Ferguson -

Beyond Lean-In: For a Feminism of the 99% and a Militant International Strike on March 8

— Linda Martin Alcoff, Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, Angela Davis, Nancy Fraser, Rasmea Yousef Odeh, Barbara Ransby & Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor - Reviews

-

Demythifying Native Americans

— Robert Caldwell -

Attica: The Revolt and Afterward

— Jack M. Bloom -

Arab Spring: Against Shallow Optimism and Pessimism

— Atef Said -

A Global Matrix of Control

— Michael J. Friedman -

The Politics of Some Bodies

— Peter Drucker - In Memoriam

-

Erwin Baur (1915-2016)

— Charles Williams -

Lillian Pollak

— Dianne Feeley

Peter Brogan interviews Kristen Buras

KRISTEN BURAS IS the author of Charter Schools, Race, and Urban Space: Where the Market Meets Grassroots Resistance (2015). She is an Associate Professor in the Department of Educational Policy Studies at Georgia State University in Atlanta and a fellow of the National Education Policy Center. Peter Brogan interviewed Buras and holds a doctorate in geography from York University in Toronto. For his dissertation he studied the ways in which school privatization and activism among teachers and parents to defend and transform public education figures into today’s Chicago and New York City school systems. He is presently employed as an organizer in Northern California with the National Union of Healthcare Workers.

WHILE PRESIDENT TRUMP has doubled down on the war against public education with Michigan billionaire and U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, the project to dismantle and privatize public education has been driven by a diverse network of think tanks, billionaire-created and supported foundations, academics and media outlets.

Sadly, if not surprisingly, the corporate education “reform” project has enjoyed support from both the Democratic and the Republican parties. Indeed, in part we should understand this inasmuch as corporate education restructuring has been a central component of the global project of neoliberal economic restructuring led by national states and institutions like the World Bank.

While schools have always played a unique role in the social reproduction of labor, expanding capital accumulation and a corporate governance model into the realm of public education in the United States, especially in cities, has proven to be a profit-making enterprise. A central vehicle of this privatized vision for education is the charter school.

Charter schools have been promoted as an equitable and innovative solution to the problems plaguing urban schools. Advocates claim that charter schools benefit working-class students of color by offering them access to a “portfolio” of school choices. Buras, an Associate Professor in Educational Policy Studies at Georgia State University, presents a very different account by chronicling the past decade of public school privatization and the struggle for education justice in New Orleans.

Her book on New Orleans — where veteran teachers were fired en masse and the nation’s first all-charter school district was developed — shows how such reform is less about the needs of racially oppressed communities and more about allowing white entrepreneurs to capitalize on Black children and neighborhoods.

Peter Brogan: Kristen, your book Charter Schools, Race, and Urban Space: Where the Market Meets Grassroots Resistance is a tour de force of the savage attacks on public education, teachers and their union in New Orleans that occurred in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. Can you outline the overall argument you make about what and who is behind this attack? What’s so special about New Orleans as a petri dish of neoliberal experimentation in education “reform?”

Kristen Buras: When Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans in 2005, the flooding and destruction were understood as “natural” events by the mainstream media. In reality, before the water had receded — indeed, while bodies were still floating in the water — powerful actors at local, state and national levels were instituting plans to rebuild New Orleans as the nation’s first all-charter school district. There was nothing “natural” about it. The speed, precision, and scope of privatization efforts were alarming.

Within days, the conservative Heritage Foundation and President George W. Bush were calling for the establishment of “Opportunity Zones” across the Gulf Coast, where so-called private-sector innovation would be unleashed to solve the problems in public schools, public housing, etc.

Within weeks, the U.S. Department of Education was offering millions of dollars to support school rebuilding, but only for charter schools. Within months, the Louisiana State Legislature passed Act 35, which manipulated the cut-point that defined failing schools and enabled the vast majority of public schools in New Orleans to be taken over by the state-run Recovery School District (RSD) and ultimately charterized.

Not long after this, unionized public school teachers in New Orleans — majority Black and a substantial portion of the city’s Black middle class — were dismissed en masse without due process and replaced by mostly white, inexperienced recruits who had no roots in New Orleans. These recruits were provided by Teach for America (TFA) and other edu-businesses known for lucrative contracts to supply transient teachers in low-income communities of color.

At the local level, Mayor Ray Nagin’s Bring New Orleans Back Commission issued a report calling for the city to be the nation’s first all-charter school district. New Schools for New Orleans, a charter school incubator founded in Katrina’s wake, facilitated this process with monies from the U.S. Department of Education and venture philanthropies well-known for supporting school privatization, including the Broad, Gates, and Fisher Foundations.

As a result, the locally elected school board was left with only a handful of public schools. All this was done without the input of affected communities. Thousands were dead, hundreds of thousands remained displaced, homes and neighborhoods were destroyed. Through purposeful intervention, rather than natural occurrence, the public schools would be wiped out as well.

As I argue, these “reforms” are premised on white supremacy and what Marxist geographer David Harvey calls “accumulation by dispossession.” That is, the assets of Black working-class urban communities, including neighborhood public schools, are put in circulation as capital for a sector of largely white entrepreneurs.

More to the point, Black students themselves are commodified and assessed based on their exchange value to charter schools, which prioritize test performance and profit over equitable education.

New Orleans serves as a warning for cities across the nation. “Consumers” beware: Public schools are closed with little community input, while education entrepreneurs acquire immense decision-making power and the funds to accompany it.

Veteran teachers are fired and replaced by transient recruits, while charter school leaders make six-figure salaries; corruption goes unchecked under the guise of charter school autonomy; and most alarmingly, Black communities are gutted in the name of rebuilding and educational progress.

The RSD never had an A-rated charter school during its tenure in New Orleans, with the exception of one school in 2016 (and that charter operator is known locally and nationally for high rates of student push out). Most schools were rated C, D, and F according to the state’s own standards. What kind of “model” is this?

PB: Can you elaborate on what a critical geographical or spatial lens brings to your analysis? Can you talk about the power of place as an explanatory tool in the book? Please elaborate on the way in which you develop a political ecology of neoliberal education policy in New Orleans? What can we draw from this as scholars and activists in the battle for education justice?

KB: I mentioned geographer David Harvey earlier. One of the points he makes is that cities are built environments. That is to say, they are organized in ways that enable capital accumulation and, I’d add, in ways that maintain white supremacy. For example, as I discuss in the book, downtown New Orleans neighborhoods, where most Black working- and middle-class residents live, are on ground that’s below sea level.

This is not by accident; rather, this is the result of Jim Crow and the fact that African Americans were prohibited from purchasing homes in other parts of the city. Many people don’t know it, but uptown New Orleans, largely white and wealthy, sits on ground that is above sea level. As a result, it’s less vulnerable.

Thus, when mass flooding occurred after Katrina in the Lower 9th Ward, it wasn’t by chance. The New Orleans Levee Board, white segregationists, and policymakers ensured that race, systematic neglect, and geography would produce these kinds of tragedies.

Restructuring and Resistance

Sadly, Katrina was not viewed by the white power structure as a tragedy. Here again, many seized the opportunity to rebuild the city — purged of allegedly criminal poor and Black people.

James Reiss, a shipping and real estate mogul, chair of New Orleans Business Council, and an appointee on the Bring New Orleans Back Commission, is quoted as saying after Katrina: “Those who want to see this city rebuilt want to see it done in a completely different way: demographically, politically, and economically.”

That’s it in a nutshell — race, space and power combined with policy to create the “new” New Orleans, with entire sectors reorganized for white venture capitalists. There would be new schools for New Orleans, new markets, but the same old exploitation.

School Facility Master Planners in New Orleans determined where schools would be closed and/or rebuilt. I’ve got a map in the book that shows how things looked just five years after Katrina. Black neighborhoods were gutted of public schools, even though the vast majority of public school students remained Black.

For the most part, charter schools were rebuilt outside of these neighborhoods, making attendance difficult as well as ensuring that African American neighborhoods lacked critical infrastructure.

What is telling, though, is the power that race and place likewise played in resistance. Policymakers and entrepreneurs underestimated how a “sense of place,” or the history of struggles that unfold in particular places and the cultural traditions and consciousness that grow from those struggles, would inspire push-back against the project of removal.

In the Lower 9th Ward, Martin Luther King Elementary School was a proud and successful neighborhood public school, itself the result of a long battle decades before Katrina. After the storm, the principal, veteran teachers and community members fought to have the school rebuilt and reopened.

One veteran teacher shared with me: “I guess a lot of people thought if you keep them [Black residents] down so long, they’ll surrender. It don’t work like that here. This is all we have. This is home. We’re not going nowhere.”

In short, officials had no plans to rebuild schools in the Lower 9th Ward, neither King nor the other four public schools that were destroyed there. Grassroots resistance was immense. A mass march and sit-in at RSD headquarters, for instance, were required to secure a habitable temporary building for King while the actual school was being rebuilt.

And that’s not the half of it. King was forced to become a charter school, the only means for reopening, and this required the school community to assemble a long and complicated proposal and then fight for its approval in the midst of rebuilding their own homes and lives.

Ultimately, we must remember that although elite networks have their own resources — primarily financial — grassroots networks also have resources, which are not often recognized for their capacity to fuel resistance.

A sense of place is one of these. And it’s not abstract or inconsequential; it’s deeply felt, rooted in history and shared cultural knowledge, and serves to ground the most difficult of battles. Activists would do well to harness the politics of place as a critical part of mobilizations against school privatization.

Neoliberalism: Race Matters

PB: Your book so effectively weaves together a class and antiracist analysis in the explanation of what underlies the radical restructuring of education in New Orleans. Can you discuss the ways in which the project to dismantle public education in New Orleans has been both a class and a racial project? What might this tell us about corporate education “reform” across the United States and around the world?

KB: I sometimes feel frustrated with a segment of white leftists who seem to suggest: If only we can rectify class exploitation and usher in a political-economic revolution, all will be well. While I agree with the political-economic critique of capitalism — Marx was dead right on issues of alienation, labor exploitation, and the need for an economy that embraces the philosophy, “From each according to his ability, to each according to his need” — I don’t believe that class division is the only challenge.

Race matters and although it may be closely related to class, it cannot be collapsed with class dynamics. Even when African Americans are upwardly mobile or hold graduate degrees or high positions, they are subject to racially inspired disrespect, micro-aggression and criminalization. They are expected to assimilate to white cultural norms. And they are viewed as beneficiaries of affirmative action, rather than hardworking, accomplished people despite racial barriers.

The mayor of the white 491-member town of Clay in West Virginia was reported by the BBC as applauding a Facebook post that called First Lady Michelle Obama, “a [sic] ape in heels.” Let me speak frankly: Michelle Obama, the nation’s first African-American First Lady, with degrees from Princeton and Harvard, is subject to derogation by a small-town white reactionary.

A leveling of the class structure will not undo white supremacy. Philosopher Nancy Fraser is right to distinguish between a politics of economic redistribution and a politics of cultural recognition. We need both and their relationship is complex.

Neoliberalism is generally understood, even by critical folks, as an iteration of capital, as a political-economic project aimed at consolidating class power. It’s that for sure, but it’s not that alone. In the case of charter schools in New Orleans (and elsewhere), new education markets and privatization are occurring in urban spaces, which means communities of color.

Neoliberalism is therefore not simply a political-economic project, but a racial one. When any sector is privatized, communities of color suffer inordinately because they are overrepresented among the poor, even though the nation’s wealth was built off their labor and their backs.

Certainly New Orleans’ tourism industry has been reliant on the exploitation of Black cultural forms and labor for white profit and enjoyment. Now charter schools are profit centers for white entrepreneurs, while Black students suffer a host of violations.

Through the lens of New Orleans, I want to show that neoliberalism is a class and race project and must be challenged on both fronts. Much of this is rooted in European colonialism, which conquered resources and lands while killing Indigenous peoples and enslaving African peoples.

Today, austerity and privatization are inflicted on people of color across the globe. Like freedom fighters of the past, we must stand against economic as well as racial oppression.

PB: Building on this, I found your use of the concept of “whiteness as a property relation” to explain some of these dynamics of great significance. Can you explain what this concept means and how you deploy it in your book?

KB: The notion of “whiteness as property” is something drawn from Critical Race Theory (CRT), a tradition that grows from the work of scholars of color in the fields of law and education. One of its guiding tenets is that racism is endemic.

CRT legal scholar Cheryl Harris (who has supported organizing efforts in New Orleans) wrote a landmark essay titled “Whiteness as Property.” In that essay she explores how white identity functions much like a property interest — that is, those who possess it have historically used and enjoyed a host of benefits and assets, while excluding communities of color from such entitlements.

In New Orleans, white entrepreneurs have seized control of a key asset in the Black community — public schools — and built a profitable and exclusionary educational system.

This is where the political ecology of neoliberal education policy comes in. There is a network of wealthy philanthropists, legislators, edu-business leaders, charter school operators, entrepreneurs and aspiring, upwardly mobile climbers — mostly white — who constitute a relatively close-knit community through which ideas, strategies, contracts and funds readily flow.

What is striking is the racial and class composition of those in the network. Yes, people of color are a fraction of this network, but on the whole the process of neoliberal urban school reform is dominated by white policy actors imposing their vision upon poor and working-class communities of color, generally without substantive input or consent. In this way, whiteness functions as a unifying identification or force leveraged for the purpose of capital accumulation.

One Black veteran teacher whom I interviewed made clear: “It’s all about the dollars. Our rights as teachers have been trampled upon. They [policymakers and charter school operators] are saying that they are revamping the schools or whatever. They get rid of everyone and they rehire whoever they want to rehire. In many cases, they replace veteran teachers [read: Black] with first, second and third year teachers [read: white TFA recruits].”

Indeed, when a class action lawsuit challenged the mass firing of New Orleans teachers, it asserted that education officials had wrongfully and intentionally interfered with teachers’ employment contracts and property rights.

In short, inexperienced TFA recruits, based on white racial identity and its association with “intelligence” and “talent” (a buzz word of TFA), dispossess Black teachers of their property rights (jobs, tenure, health insurance benefits, pension), assume their positions, and then ultimately translate their experience into concrete material advantages, whether by advancing in the entrepreneurial network, having loans forgiven as a result of teaching, gaining favor in law school admission, etc.

In 2010, there was a high-stakes public hearing regarding the future governance of RSD charter schools in New Orleans. Would they remain under state control or return to the control of the locally elected Orleans Parish School Board? One long-time African American public school advocate expressed her disgust over venture-driven reform through top-down governance by outside (white) leaders:

“I resent the fact that Paul Vallas [RSD superintendent at the time] came here from out of town. He said to New Orleans residents: You cannot take care of your community or your schools. So we’re bringing people from out of town [white] to come here and charter your schools and run your schools. There are a lot of intelligent people here that are indigenous [Black] to this community. We all need to fight for local governance and input, so that we can properly educate our children and not let them be experiments.”

That’s whiteness as property. In the book, there are a myriad of infuriating and indefensible examples as well as several diagrams that reveal some of the network players. This is not conspiracy theory; there are real people with real interests doing some really destructive things for their own material advancement.

Grassroots Community Fighters

PB: You are a New Orleans native and scholar who firmly places herself in solidarity with the struggle of African American communities fighting against the destruction of public schools and African American neighborhoods, of which schools have historically been the heart. Can you talk about your motivations for writing the book, your relationship to those grassroots organizers and community fighters who are contesting these policies, and the role of solidarity research more generally in the fight for education justice and radical transformation?

By way of example, can you elaborate on the evolution of the Urban South Grassroots Research Collective for Public Education?

KB: I’m not an “Ivory Tower” academic. As a public intellectual, critical race theorist and an anti-racist white person, the validity of my work is gauged by the degree to which it responds to the real concerns and needs of communities, especially those historically marginalized by race and class.

My research in New Orleans is not an intellectual or theoretical exercise; education policy has life and death consequences for children, families, and neighborhoods. My research is the result of an ongoing and collaborative dialogue with grassroots activists, linked to strategic forms of organizing and resistance.

Carter G. Woodson, the father of African-American history, held a doctorate from Harvard but used his intellectual resources and political will to work with teachers and communities to rectify the absence and gross misrepresentation of African and African-American experience in textbooks and elsewhere. If our work doesn’t potentially contribute to the struggle for liberation, then what’s the purpose?

The Urban South Grassroots Research Collective (USGRC) has been one avenue for doing such work. I co-founded USGRC with various long-time grassroots cultural and educational organizations in New Orleans. Allied scholars work in solidarity with veteran teachers, teacher unionists, education and youth organizers, cultural workers and community elders by collaborating to develop questions focused on equity in public education.

This process facilitates grassroots research that highlights the voices, experiences, and concerns of racially and economically oppressed communities. Finally, research findings are disseminated locally and nationally in an effort to support a public education system that serves all communities.

Allow me to provide a few illustrations of my work with USGRC. My previous book Pedagogy, Policy, and the Privatized City: Stories of Dispossession and Defiance from New Orleans, was co-authored with Students at the Center, a 20-year-old writing and digital media program founded by veteran teachers and students in New Orleans.

This book pulls together the counterstories of dispossessed African American youth, revealing the devastating effects of the post-Katrina attack on public schools and public housing. At the same time, social justice scholars from an array of sister cities responded to students’ stories, drawing connections to struggles far and wide.

Robin D. G. Kelley wrote the book’s Foreword, calling it “one of the most radical works of collaboration I’ve seen [in the last four decades].” The stories in that book have been read by youth in high school classrooms as well as by policymakers. We try to work organically at all levels.

Take, for example, the last chapter of the current book Charter Schools, Race, and Urban Space. It was co-authored with grassroots members of USGRC and is framed as a “warning for communities” nationally based on our experiential knowledge and research on charter schools in New Orleans. The lessons in that chapter, however, are ones that we have disseminated not only in scholarly venues, but community-based ones as well.

For instance, those warnings were placed on a flyer distributed during organizing events and were the focus of radio and newspaper interviews. Dr. Raynard Sanders, former New Orleans high school principal and host of the radio program “The New Orleans Imperative,” is a member of USGRC and we’ve had many on-air dialogues and exchanges with community members.

I have co-presented with USGRC members at national conferences, such as the American Educational Research Association, as community members are not usually present in such spaces, even though they are the real experts on the consequences of these reforms. At the same time, we have organized forums in neighborhood bookstores, union halls and local schools, where community members addressed teachers, teacher educators, and education researchers hailing from cities nationwide.

Moreover, we have traveled together to cities where the New Orleans model was under consideration, to meet with legislators, teachers, parents, students and organizers and share the reality of “reform” in New Orleans.

Convening on the Anniversary

Perhaps most notably, in 2015 USGRC organized a community-centered education research conference marking the ten-year anniversary of Katrina and the impact on public schools nationwide. This convening brought together critical scholars and education activists from ten cities where the New Orleans model was under consideration or had been adopted.

It was imperative to challenge the dominant narrative of charter school success. A pre-conference bus tour took folks around the city, narrated by parent advocate and USGRC member Karran Harper Royal. People were able to see what had happened to neighborhood schools and witness firsthand the uneven racial geography.

Then, over the course of two days, they were able to hear from community members about their experiences in an all-charter school system — disenfranchisement, the mass firing of veteran teachers, new teachers with little knowledge and little respect for the community, discrimination against students with disabilities, long commutes required by the closure of neighborhood schools, complex and exclusionary application processes, self-appointed charter schools boards, and more.

We also shared a documentary produced by filmmaker Phoebe Ferguson and fellow community activists, “A Perfect Storm,” which tells the story of the takeover. (Three existing episodes are available on YouTube — readers should see them.)

Organizers who traveled from Boston, Chicago, Detroit, Indianapolis, Little Rock, Milwaukee, Memphis, Nashville, Newark, New York City and Philadelphia listened, shared resources, strategized, networked and renewed their commitment to defend public education.

A theater performance, city-to-city storytelling forum, and open-mic “dream aloud” provided the space for articulating shared concerns and formulating alternative visions. Additionally, the Mardi Gras Indians joined us, wearing hand-beaded suits and using song, dance, and oral history to link present freedom struggles to those of New Orleans ancestors and the Black Diaspora.

Critical researchers connected with activists and situated the New Orleans struggle in a wider historical context, while education bloggers with Huff Post, Public School Shakedown, Cloaking Inequity, EduShyster, Crazy Crawfish, Mercedes Schneider’s EduBlog, and many others used social media to stir things up.

The New Orleans Tribune, the nation’s first Black daily newspaper, got word out, too. Meanwhile, the American Federation of Teachers, National Education Association, Southern Education Foundation, Southern Initiative Algebra Project and others offered support.

USGRC is a hybrid and complex network that melds critical research with grassroots activism. Our efforts evolve organically as the ground moves under our feet, sometimes because we shake it up and sometimes because of shock waves and agendas emanating from above.

PB: Finally, you highlight some incredible examples of resistance to these policies but also a number of important examples of radical, place-based critical education practice in New Orleans. Can you say a little about these examples and something about what broader lessons the education justice movement might take from them?

KB: This is one of the tragedies of firing Black veteran teachers who are indigenous to the community. They possess intimate knowledge of the culture and history of New Orleans, particularly of Black struggle and resistance. There are many powerful examples of place-based education, which is essential to the critical consciousness and survival of Black youth.

How can those from outside of the community teach in culturally relevant ways, especially when they either don’t know or reject as dysfunctional the culture of the students they are teaching?

Veteran teacher Amelie Prescott, who identifies as a New Orleans Black Indian, founded an arts-as-healing program called the Mos Chukma Institute; Mos Chukma means “good child” in the Houma language. This program uses art and cultural knowledge to support education and resilience. An artist-educator with the program explained to me:

“Students do not question the commitment of their [veteran] teachers. The teachers are sophisticated, master teachers whose dedication goes beyond the classroom. The children can feel this — they understand the difference between a community member and a visitor; someone who has one foot out the door; someone who does not try to understand them or may have another agenda entirely.”

Likewise, the aforementioned Students at the Center (SAC) program represents critical place-based education praxis. Students narrate their lives, schools, and neighborhoods in oral, written and digital forms, and use this knowledge to engage in an array of transformative projects.

Just prior to Katrina, for instance, SAC was planning Plessy Park, an area where the legacy of Homer Plessy and other New Orleans civil rights activists would be recognized, with student writings creating a bridge between past and present activists.

Despite SAC’s pedagogy, Frederick Douglass High School, one of the schools where SAC was located, was closed against the will of the community. The building was handed over to a charter school operator that embraces a “No Excuses” model, replacing historically situated educational practices with narrow, standardized curricula and an abusive regime of discipline.

Cherice Harrison Nelson, a veteran teacher of more than 20 years and raised in the Mardi Gras Indian tradition, was fired alongside thousands of other New Orleans teachers.

Harrison Nelson developed a Jazz Studies curriculum utilized across Louisiana; it included musical appreciation, language arts, math, history and geography. Yet she and other veteran teachers, who connected place and pedagogy in meaningful and critical ways, were replaced by TFA recruits.

Since so many “reformers” are outsiders to the communities they attempt to colonize, they do not feel a connection to place except as a site ripe for “redevelopment.” Community members have a stake in place, it is dear to them, it holds memories and is often tied to cultural traditions, not to mention the blood, sweat and tears invested in centuries of struggle.

As a result reformers often confront strong resistance, as when alumni affiliated with historic public high schools protest the takeover of those schools by charter operators. In one instance, the new principal could not enter the school because alumni defended their alma mater by creating a human barricade.

There’s something to be learned from this. The invader never knows the territory as intimately as the invaded. The former may have more fire power, but the latter are at home. No one gives up home without a fight.

March-April 2017, ATC 187