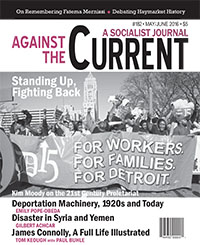

Against the Current, No. 182, May/June 2016

-

Politics of the New Abnormal

— The Editors -

Why Blacks Vote for "Pragmatism"

— Malik Miah -

"This Deportation Business": 1920s and the Present

— Emily Pope-Obeda -

Trouble Down in Texas (and elsewhere)

— Dianne Feeley -

Disasters in Syria and Yemen

— an interview with Gilbert Achcar -

Russia's Intervention and Syria's Future

— Gilbert Achcar -

Fatema Mernissi: A Pioneering Arab Muslim Feminist

— Zakia Salime -

Destroying Detroit Schools

— Dianne Feeley and David Finkel -

U.S. Labor -- What's New, What's Not?

— Kim Moody -

Auto's Permanent Temporaries

— Dianne Feeley - The Murder of Berta Cáceres

-

Free Oscar Lopez Rivera Now!

— Steve Bloom -

Homonationalism and Queer Resistance

— Peter Drucker - An Introduction to the Life of James Connolly

-

James Connolly and the Easter Uprising

— Paul Buhle -

American Literature and the First World War

— Tim Dayton - Review Essay on Haymarket

-

The Contested Haymarket Affair: 130 Years Later

— Allen Ruff -

Messer-Kruse's Haymarket History

— Rebecca Hill - Reviews

-

Water in a World in Crisis

— Jan Cox -

Standing Against Counterrevolution

— David Finkel -

Inside/Outside the Campus Box

— Michael E. Brown

Dianne Feeley and David Finkel

THE DETROIT PUBLIC School system (DPS) has been under state control for 15 years, the last decade under the direction of a series of Emergency Managers.

The result has been a staggering debt, now more than half a billion dollars, with a 50% decline in the number of students served. More students attend charter schools than the public system, but as there is no oversight over charters, poorly run schools continue year after year.

Over the past decade 160 Detroit schools of various types have opened or closed. In some neighborhoods there is no public school, only charters or the Education Achievement Authority (EAA), the disastrously failing system set up by Governor Rick Snyder. Yet neither the Governor nor the legislature is willing to accept responsibility for the chaos, assume the debt and return the public school system back to local control.

As teachers and parents attempt to make plans for the fall semester — not knowing where their kids will be in school, or where they’ll be teaching — the stress is taking a severe toll all around. It looks like a calculated ploy to prevent teachers and the community from getting organized.

Meanwhile the rightwing Michigan legislature is bickering over how to design legislation to use the DPS debt, which the state caused, to further weaken the bargaining power of the Detroit Federation of Teachers and prevent citizen control through an elected school board.

The Governor and legislature’s insistence on “financial oversight” is their club for completing the effective destruction of Detroit’s public school system — a goal that education activists feel was the purpose behind imposing Emergency Managers from the beginning.

The legislature is also debating a proposal that would eliminate state payments for high school students’ SAT tests — further raising the costs to families trying to get kids into college.

The first Emergency Manager over the Detroit schools was Robert Bobb (2009-11), who built new schools with huge overruns and signed a $40 million book contract for a curriculum that was never used. One his top appointees, Barbara Byrd Bennett, subsequently became CEO of the Chicago school system and is now on her way to federal prison in a corruption scheme there.

Last winter Detroit teachers walked out to protest leaking roofs and mold, and registered complaints about the lack of books for their classrooms. A citizens’ audit would reveal massive corruption under the Emergency Manager system.

Michigan voters in fact rejected the use of Emergency Managers through a referendum vote in November 2012, but the legislature in its contempt passed an even more severe version during the lame-duck session that was quickly signed into law by Snyder. To add insult to voters, the new bill was designed to be veto proof.

The media now talk about cases where the EM “worked,” as with the Detroit city bankruptcy, and where it “failed,” as in Flint, where to save a few bucks the manager was willing to risk poisoning all who used the water. As a result, Flint residents suffered from both lead contamination and Legionnaire’s Disease that killed 12 and sickened nearly 100. But when the Flint City Council, under pressure from residents, voted to return to the Detroit water system, the EM prevented that from happening.

There are in fact no “good” versus “bad” examples. A case in point: the notorious Flint Emergency Manager Darnell Earley, testifying before Congress, attempted to blame others for what happened on his watch. But what was he doing when called before Congress? He was the current EM over the Detroit Public Schools!

It’s the system of one-man (it’s almost always a man) dictatorship that’s ruinous — although, to be sure, the individual managers have turned out to be mostly arrogant, corrupt and certainly inept administrators.

In all cases the EM law took away the rights of citizens, prioritizing debt payment. For example, Michigan schools receive a minimum of $7,400 per pupil funding — but for Detroiters $1,200 is skimmed off the top to pay the interest on the growing debt. Left in the shadows is an accounting of the reasons for this massive debt. So the students and families who depend on decently funded and stable schools wind up paying the costs of a criminal system.

May/June 2016, ATC 182