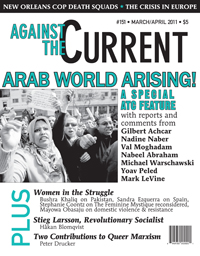

Against the Current, No. 151, March/April 2011

-

Change of the Century

— The Editors -

New Orleans' Police Death Squads

— an interview with Malcolm Suber -

Whither Social Security?

— Malik Miah -

Campaigning with Issues

— an interview with Ann Menasche -

Renewing New York

— an interview with Howie Hawkins -

Stieg Larsson in the Struggle

— Håkan Blomqvist - Arab World Uprising

-

Egypt and Beyond

— an interview with Gilbert Achcar -

The Meaning of the Revolution

— Nadine Naber -

Women, Revolution and the Future

— Val Moghadam -

From Tahrir to Palestine

— Nabeel Abraham -

A View from Israel

— Michael Warschawski -

Egypt Shakes the World

— Susan Weissman interviews Yoav Peled & Mark LeVine - Crisis in Europe

-

FRANCE: Battling Over Pensions

— Jason Stanley -

IRELAND: Slaying the Celtic Tiger

— John O'Connor -

GREECE: The Crisis Continues

— Nikos Tamvaklis -

UNITED KINGDOM: Students Fight the Fees

— interview with Ashok Kumar -

SPAIN: Women's Crises

— Sandra Ezquerra - Women in the Struggle

-

Pakistan's Dark Journey

— Bushra Khaliq -

Interrogating the Feminine Mystique

— an interview with Stephanie Coontz -

Claiming the Power to Resist

— Mayowa Obasaju - Triangle Fire Remembered

- Reviews

-

Arabs and the Holocaust

— David Finkel -

Toward A Queer Marxism?

— Peter Drucker

an interview with Gilbert Achcar

GILBERT ACHCAR, WHO grew up in Lebanon, is professor of development studies and international relations at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), London, and author most recently of The Arabs and the Holocaust: the Arab-Israeli War of Narratives, which is reviewed elsewhere in this issue. Farooq Sulehria interviewed him on February 4. The first question here is an excerpt from that interview, which is available at http://www.socialistproject.ca/bullet/459.php#continue. David Finkel from the ATC editorial board spoke with him on February 14, and posed the second question on the regional perspective.

Farooq Sulehria: The Western media are hinting that democracy in the Middle East would lead to an Islamic fundamentalist takeover. We have seen the triumphal return of Rached Ghannouchi to Tunisia after long years in exile. The Muslim Brotherhood is likely to win fair elections in Egypt. What is your comment?

Gilbert Achcar: I would turn the whole question around. I would say that it is the lack of democracy that led religious fundamentalist forces to occupy such a space. Repression and the lack of political freedoms reduced considerably the possibility for left-wing, working-class and feminist movements to develop in an environment of worsening social injustice and economic degradation.

In such conditions, the easiest venue for the expression of mass protest turns out to be the one that uses the most readily and openly available channels. That’s how the opposition got dominated by forces adhering to religious ideologies and programs.

We aspire to a society where such forces are free to defend their views, but in an open and democratic ideological competition between all political currents. In order for Middle Eastern societies to get back on the track of political secularisation, back to the popular critical distrust of the political exploitation of religion that prevailed in the 1950s and 1960s, they need to acquire the kind of political education that can be achieved only through a long-term practice of democracy.

Having said this, the role of religious parties is different in different countries. True, Rached Ghannouchi [the Tunisian Islamist leader] has been welcomed by a few thousand people on his arrival at Tunis airport. But his Nahda movement has much less influence in Tunisia than the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt. Of course, this is in part because Al-Nahda suffered from harsh repression since the 1990s. But it is also because the Tunisian society is less prone than the Egyptian to religious fundamentalist ideas, due to its higher degree of Westernization and education, and the country’s history.

But there is no doubt that Islamic parties have become the major forces in the opposition to existing regimes over the whole region. It will take a protracted democratic experience to change the direction of winds from that which has been prevailing for more than three decades. The alternative is the Algerian scenario where an electoral process was blocked by the army by way of a military coup in 1992, leading to a devastating civil war for which Algeria is still paying the price.

The amazing surge of democratic aspirations among Arab peoples of these last few weeks is very encouraging indeed. Neither in Tunisia, nor in Egypt or anywhere else, were popular protests waged for religious programs, or even led principally by religious forces. These are democratic movements, displaying a strong longing for democracy.

Polls have been showing for many years that democracy as a value is rated very highly in Middle Eastern countries, contrary to common “Orientalist” prejudices about the cultural “incompatibility” of Muslim countries with democracy. The ongoing events prove one more time that any population deprived of freedom will eventually stand up for democracy, whatever “cultural sphere” it belongs to.

Whoever runs and wins future free elections in the Middle East will have to face a society where the demand for democracy has become very strong indeed. It will be quite difficult for any party –– whatever its program –– to hijack these aspirations. I am not saying that it will be impossible. But one major outcome of the ongoing events is that popular aspirations to democracy have been hugely boosted. They create ideal conditions for the left to rebuild itself as an alternative.

Against the Current: This is a speculative question, of course, but can you address the possibilities for the revolution in Tunisia and Egypt to spread more widely, and the obstacles facing it?

GA: Protest is already unfolding in Yemen as a mass movement, but it is hindered there by the tribal dimension. The government is mobilizing the tribes that are loyal to the head of the regime. Similarly, tribal or ethnic factors can be used in Jordan to block the progress of the protest movement.

In Algeria, on the other hand, there has been repression by a huge mobilization of security forces, and in countries like Syria, Libya and Iran the movements have not even been able to start until now. The regime in Iran is trying to demoralize the population by tremendously increasing the number of executions.

Tunisia and Egypt were two obvious candidates. In Tunisia the social base of the regime was very narrow, and in Egypt there was a real opposition. For the rest of the region, although certainly the “objective” conditions are very ripe for protest, the “subjective” conditions necessary are really on a high level to confront these extremely repressive regimes, which are completely insensitive to any western public opinion or any form of influence. Egypt and Tunisia are of course heavily dependent on western ties.

Yet who could have predicted what has already occurred? The shock wave is here, and when you have an earthquake you cannot predict exactly when the aftershock will occur. Sooner or later all the countries I have mentioned will have their explosion, but when it will happen is very difficult to tell — and in countries like Syria or Iran or Libya, if we have real serious protests it can turn much bloodier.

In Egypt itself, the military is continuing to hold power even more directly. We have to celebrate what has happened, even while we remain very sober.

ATC 151, March-April 2011