Against the Current, No. 42, January/February 1993

-

The New-Old Political Order

— The Editors -

Imagine The Possibilities

— Samuel Farber -

The Rebel Girl: Measure 9 Dies; OCA Vampire Lives

— Catherine Sameh -

Bill Clinton in the World

— Mike Zielinski -

Slave Women, Family and Property, Part 3

— Cecilia Green -

Revolution and Justice

— Justin Schwartz -

Random Shots: Campaign and Other Leftovers

— R.F. Kampfer - Perspectives on Environmental Struggle

-

Report from New Orleans

— Rick Wadsworth -

What Is Environmental Racism?

— Kathryn Savoie interviews Bunyan Bryant -

Retrospective on Rio

— Maby Velez -

Stop the Poisoning of Peru

— Hugo Blanco -

The Environmentalism of the People

— Hugo Blanco -

Radiation: A New Smallpox Blanket

— Jennifer Viereck -

Why We Need a Political Ecology

— Chris Gaal -

Ecology and Radical Economics

— Chris Gaal -

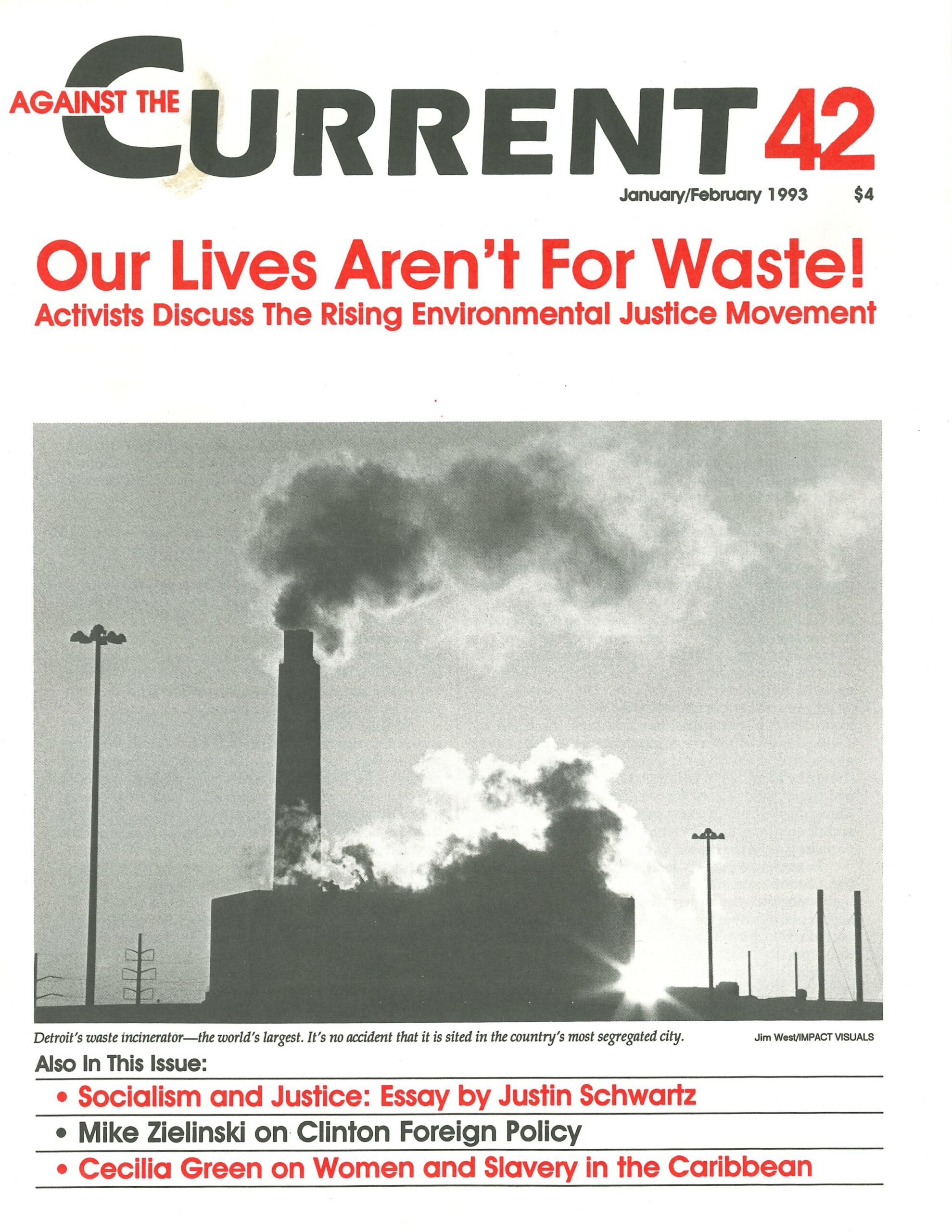

The Fiery Furnace of Neb-u-chad-nez-zar

— Don Fitz - Reviews

-

Who's Got the News?

— E. San Juan, Jr. - In Memoriam

-

Elinor Ferry (1916-1992)

— Nora Ruth Roberts

E. San Juan, Jr.

Control of the Media in the United States:

An Annotated Bibliography

Edited by James Bennett

New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1992), xxviii + 819 pp. $125 cloth.

IN MASS COMMUNICATION and American Empire (1969) and The Mind Managers (1973), Herbert I. Schiller, among others, called our attention to the intensifying domination of the mass media and other institutional forms of communication by the corporate state and the power behind it: the emerging complex of transnational corporations. Other critics of the corporate Leviathian, like Ben Bagdikian, Robert Cirino, Noam Chomsky and others, pursued Schiller’s lead through the seventies, eighties, and nineties.

Still accumulating parallel to the global expansion of business-managed computerized communication, this vast archive of information and knowledge has now finally been made accessible to us through the painstaking and scrupulous labor of James Bennett, professor of English literature at the University of Arkansas, and his staff. (Bennett has published an earlier and equally ambitious work, Control of Information in the United States, which complements this endeavor.)

What is admirable about this stunning achievement is its wide-ranging scope and substantial synopsis of key entries detailing, as Bennett puts it in the introduction, “all aspects of communication from ownership to control to actual processing and manufacturing of news to the content of news up to the effects of the presentation.”

The documentation of this rich material is structured in three parts.

Part I deals with “The Structures of the Corporate State” including such “master institutions” as corporations and finance, the government bureaucracy, and secondary institutions that administer what Foucault calls “disciplinary regimes” of law, science and technology, religion, education, medicine, and sports.

Part II examines “The Media Complex” involving the organization of mass media, advertising and public relations, electronic and print media, art and music.

Part III deals with “Alternatives” that seek to challenge the Establishment institutions on all fronts. An “Author Index” and “Subject Index” guides us to individual entries.

Some 4600 works are catalogued. Five hundred fifty books are listed, concerned with how the corporate state fabricates literally and figuatively the political and social reality needed to maintain its hegemonic rule in the form of the National Security State. While the emphasis is on political society (economic, political, military), civil society–except the family–is covered.

The principle of selection pivots on the theme of how “discourses and media, the channels of mediation, are shown to be inseparable from the structures of power.” While performing their functions in stabilizing and reinforcing the market system, all the major institutions in the United States produce, distribute and circulate a system-supportive network of ideas, beliefs, values, and practices through the manifold communication media which is chiefly funded by tax dollars, but controlled by the minority elite.

Bennett lists books that expose the linkages of government and private business (already pointed out by mainstream scholars) that also offer programs to counter official power and promote individual citizens’ autonomy.

A Complex of Domination

The bulk of this volume, not equalled by other conventional academic bibliographies in political science or journalism, is devoted to annotating 3500 books and articles examining the role of all discourses and media in promoting what Bennett calls “big business/big government symbiotic relationship.”

An example would be how stories in The Saturday Evening Post contribute to people’s acceptance of the legitimacy of corporate power in the administered state masquerading as genuinely consensual democracy.

Bennett’s brilliant introduction to this section, entitled “The Media Complex,” sums up what Gramsci called the process of hegemonic domination: how American civil religion historically emerged through the mediation of all forms of media–here the reference of “media” would embrace all cultural practices and institutions from patriotic parades, museums, sports rituals and so on, up to ideological myths and symbols of manifest destiny, the Western cowboy hero, and the freedoms of consumerist society.

After a cogent historical review of the rise of nationalist statism, Bennett forcefully sums up: “The cultural industry and the educational system function as the chief institution for legitimating the established hierarchy of power.”

In the information society of most industrial societies where total commodification prevails, where monopoly of knowledge equals power, obedience to the logic of private consumption in everyday life has been so internalized as to appear “common sense,” is there any hope for radical social change, for a thoroughgoing transformation of institutions and daily practices?

An approach to this problem is broached in the concluding section. While the first two parts also provide us, in general, the equipment and orientation for answering this question, the third and last part of Bennett’s archive is dedicated to changing the status quo toward genuine political equality by undoing the corporate stranglehold on information and media.

How can the people seize control of the “consciousness industry” and suppress the official monologues of the Establishment elite? Bennett cites two proposals: first, the establishment of an alternative economic structure to reduce inequalities due to ownership and control of firms; and second, the exploration of ways for people “to reclaim their own voices” and eliminate “the technology of Panopticon control,” as suggested by Sue Jansen.

These two proposals are not exclusive but, I think, their combination seems problematic unless we specify the historical conjunctures of their effectiveness: We are all aware that hegemony precisely implies the capacity to co-opt and incorporate the opposition.Undeterred, Bennett maps some of the territory occupied by alternative media like The Progressive and scarcely known publications like Virginia Pilot and Mountain Eagle, upholding the example of pioneering individuals like Bill Niguts (about whom I haven’t heard until now). He emphasizes the need to investigate the truth and disseminate this liberating knowledge and information as widely as possible.

Lest readers mistake this for a reformist call, Bennett immediately qualifies it with this remark: “Until criticism can transform the principles and structures of institutions, the struggle for political equality will always lag far behind established power…. In addition to criticism, exposure, imagining alternative `ways of worldmaking,’ and physical protest, we must expand our influence within the major reality-making institutions in order to change them.” Thus a fusion of theory and mass practice is required to carry out a strategy of counterhegemony.

Media of Our Own?

Part III compiles a list of guides for charting the terrain of struggle within the existing institutions, as well as for inventing alternative means of communication. Given the retooling of corporate transnational capitalism within the new “postmodern” world-system, I think this twofold strategy is inevitable and necessary.

And so, in tune with the redrawing of the imperial formations in our threatened ecosystem, Bennett appropriately evokes the Declaration of the International Federation of Journalists as well as the UNESCO Declaration in his concluding stress on a planetary “vision of mass media promoting peace and human rights instead of ethnocentric and nationalistic myths,” in particular the role of media in opposing racism and war and supporting oppressed peoples.

Since transnational corporate power spreads its tentacles into every nook and cranny of the globe, it is logical to insist on an international campaign to free all people from its oppressive control. But Bennett of course is not trumpeting “world revolution” and synchronized seizure of the means of communication everywhere.

His project is modest: He focuses on media in the United States since pax Americana (before the rise of Germany and Japan as the new economic powers) installed the unrivalled ideological hegemony of the capitalist dispensation throughout the “free world.”

This milieu of a “democratic” market-system now claims to be universal and totalizing, especially with the demise of the Soviet Union and the accelerated colonization not only of erstwhile competing regions like China or Vietnam but also of the last remaining hinterlands of sexuality and the unconscious.

UNESCO is, to be sure, not a revolutionary organization committed to overthrowing the “free enterprise” system. Nor are many of the authorities Bennett cites who criticize the betrayal of the principles of liberal democracy.

Yet, in the context of the ascendancy of the Reagan-Bush neoconservatism, Bennett in fact becomes a subversive by invoking the premises of U.S. popular democracy (such as those embodied in the Constitution’s Bill of Rights).

Essentially, he believes that ordinary people cannot be fooled all the time and that, properly informed and their critical consciences aroused, the grassroots constituencies will revolt and put an end to corporate perversion of media and knowledge.

In this process of social enlightenment, the agency of intellectuals (in Gramsci’s broad sense of educators) and their mobilization is urgently needed. Bennett’s book is a powerful catalyst for this job, a testimony itself to the breadth, vitality, and resourcefulness of the growing oppostion challenging the rule of corporate statism.

Democratic Energy

After the second world war, the revolution in electronic technology and mass communication led prophets like Marshall McLuhan and other futurologists obsessed with pragmatic solutions to injustice and alienation to celebrate the advent of a new “global village” of prosperity and understanding. The media enthusiastically publicized them.

With the public’s relatively politicized consciousness about immense ecological damage wrought by corporate industrial exploitation all over the world and the worsening dehumanization of everyday life in every region where class, gender and racial conflicts are reproduced by the market system, the prophets of the media revolution can no longer so easily deceive the victims as before.

Proof of this is Bennett’s valuable reference work which articulates the enormously rich modes of resistance to the most crucial forms of oppression–I think the book documents control not only of the media but of the bodies and souls of citizens–and at the same time catalyzes the energies of popular egalitarian democracy, which Bennett believes coincides with the authentic historic legacy of the struggles of multiracial citizens in this North American sphere of the continent.

No library or organization committed to fostering an enlightened and socially responsible citizenry can do its job without securing this book.

January-February 1993, ATC 42