Against the Current No. 19, March/April 1989

-

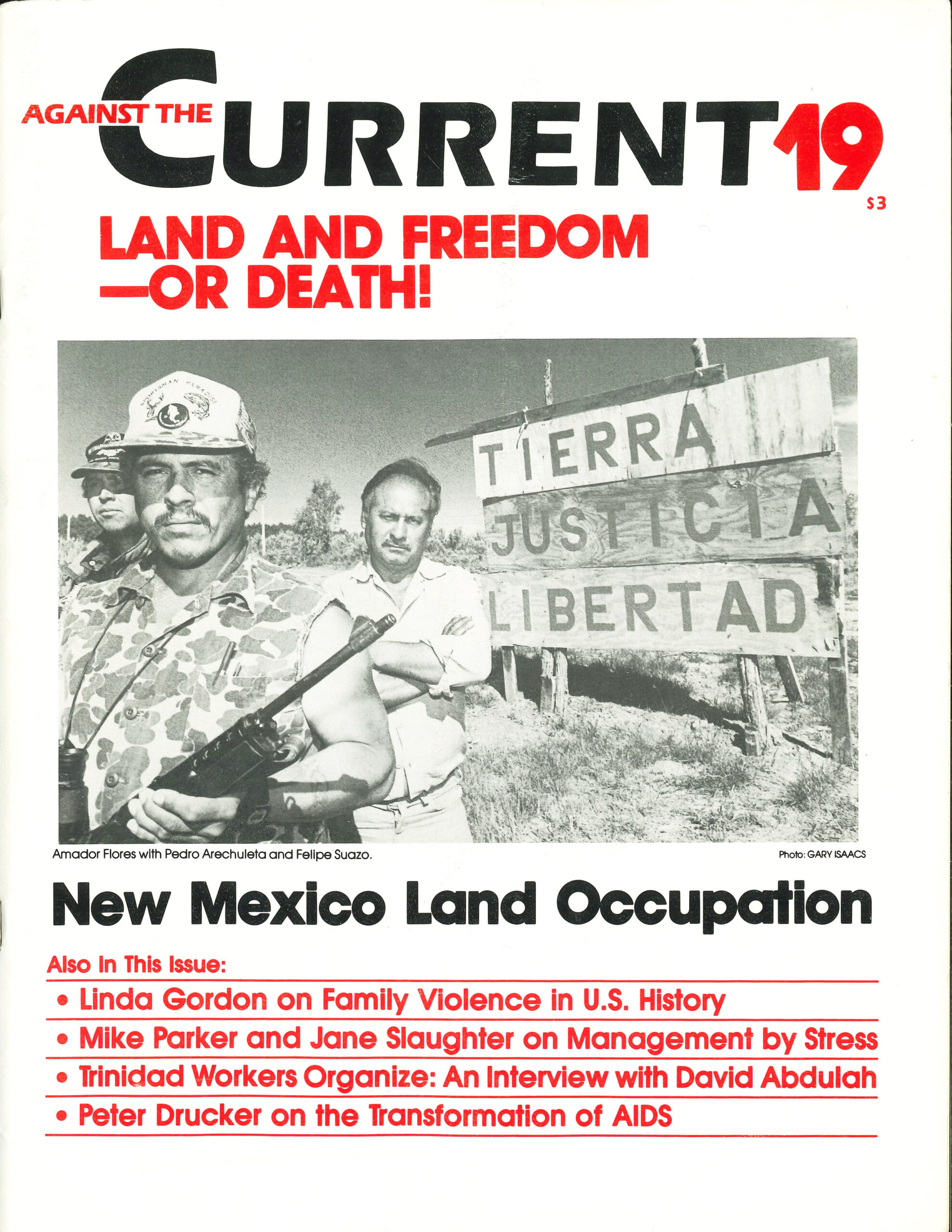

Struggling vs. Theft of Communal Lands in New Mexico

— Alan Wald - Mexican Activist "Disappeared"

-

Defending the Right to Choose

— Norine Gutekanst -

The Transformation of AIDS: Polarization of a Movement

— Peter Drucker -

The Politics of Child Sex Abuse

— Linda Gordon -

Random Shots: Wisdom of Solomon

— R.S. Kampfer - Capital Restructures, Labor Struggles

-

Free Trade . . . for Big Business

— Francois Moreau -

Management's "Ideal" Concept

— Mike Parker and Jane Slaughter -

Other Points of View

— Mike Parker and Jane Slaughter -

U.S. Labor & Foreign Competition

— Milton Fisk -

Review: Class Struggles in Japan Since 1945

— James Rytting -

Trinidad: Toward a Party of the Workers

— David Finkel & Joanna Misnik interview David Abdulah -

A Brief Glossary of Abbreviations for Caribbean Parties

— David Finkel - Dialogue

-

Reclaiming Our Traditions

— Tim Wohlforth -

A Comment on Afghanistan

— David Finkel -

Socialism from Below, Not the PDPA

— Dan La Botz -

Islam, Feminism and the Left

— Christy Brown -

A Brief Rejoinder

— R.F. Kampfer - In Memoriam

-

In Honor of Max Geldman

— Leslie Evans

Mike Parker and Jane Slaughter

THE CORPORATE BUZZWORD of the 1980s is “competitiveness.” Toward that end, companies in industries ranging from auto to telecommunications to papermaking are adopting new strategies to increase labor productivity. Employers have always looked for ways to introduce speedup. The difference today is that they claim their new production system, sometimes called the “team concept,” increases workers’ skills, imbues them with dignity and even implements worker control of the shop floor.

THE CORPORATE BUZZWORD of the 1980s is “competitiveness.” Toward that end, companies in industries ranging from auto to telecommunications to papermaking are adopting new strategies to increase labor productivity. Employers have always looked for ways to introduce speedup. The difference today is that they claim their new production system, sometimes called the “team concept,” increases workers’ skills, imbues them with dignity and even implements worker control of the shop floor.

Another difference from speedup campaigns of the past is that many top union leaders defend the new methods ideologically, echoing the employers’ claims. “We have more in common than we have in conflict,” is the cooperating unionist’s new motto. In a December 25, 1988 article in the New York Times, which attacks Mike Parker and Jane Slaughter’s book on the new methods, Choosing Sides: Unions and the Team Concept (Boston: South End Press, 1988), United Auto Workers (UAW) board member Bruce Lee even claims there has been “a revolution on the shop floor.” And because of this worker control rhetoric, many intellectuals who are socialists and allies of the labor movement have become defenders of the team concept, without examining what really goes on in the plants.

In the auto workers’ union, the team concept is a key issue in the “new directions” trend, the most serious challenge to the current union leadership in years. At a January rank-and-file conference near Detroit attended by 900 UAW members, speaker after speaker got up to denounce the plan. “There’s a new word for concessions, and it’s team concept,” said one.

Choosing Sides has generated considerable controversy. Excerpts have appeared in the Washington Post, the New York Times, MIT’s Technology Review and industrial relations publications. Most important, the book is getting wide circulation among union members. In some auto plants more than 100 copies have been sold and the book is regarded as the reference for dealing with the team concept.

In this excerpt from Choosing Sides, the authors spell out the workings of the employers’ most advanced version of team concept, which they call “management by stress.”

OVER THE LAST decade, while the U.S. auto industry was in a tailspin, several Japanese automakers established factories in the United States: Honda in Ohio, Nissan in Tennessee, Mazda in Michigan, Mitsubishi in Illinois and Toyota in California and Kentucky. These plants achieved stellar productivity and quality figures using management techniques imported from Japan. Toyota accomplished these numbers in a joint venture with General Motors (GM), using a former GM plant and a United Auto Workers workforce. The joint venture is called New United Motors Manufacturing Inc. NUMMI. More than any other single plant, NUMMI became the one for U.S. management to watch.

Although management uses the term “synchronous production” to describe this model, we have used the term “management-by-stress” (MBS) because it highlights the way stress serves as the force that rives and regulates the production system.(1)

Speedup: Stressing the System

Management-by-stress goes against many traditional U.S. management notions. It even seems to go against common sense. Isn’t it logical to protect against possible breakdowns and glitches by stockpiling parts and hiring extra workers to fill in for absentees?

Instead, the operating principle of management-by-stress is to systematically locate and remove such protections. The system, including its human elements, operates in a state of permanent stress. Stressing the system identifies both the weak points and those that are too strong. The weak points will break down when the stress becomes too great, indicating that additional resources are needed. Just as important, points that never break down are presumed to have too many resources, and are thus wasteful.

The andon board illustrates how management-by-stress works. Andon is a visual display system, usually including a lighted board over the assembly line showing each work station. Most andon displays use one or two colors combined with chimes, buzzers or sirens. For illustration purposes, imagine a variation where the status of each station is indicated with one of three lights:

GREEN-production is keeping up and there are no problems.

YELLOW-an operator is falling behind or needs help.

RED-problem requires stopping the line.

In the traditional U.S. operation, management would want to see nothing but green lights and would design in enough slack to keep it that way. In such plants individual managers try to protect themselves with excess stock and excess workers to cover glitches or emergencies. CYA (cover your ass) is considered prudent operating procedure.

But under management-by-stress, “all green” is not a desirable state. It means that the system is not running as fast or efficiently as it might. If the system is stressed (say by speeding up the assembly line), the weakest points become evident and the yellow lights go on. A few jobs will go into the red and stop the line. Management can now focus on these few jobs and make necessary adjustments.

A NUMMI manager explains the process to workers by comparing it to their experience when the plant was run by General Motors:

“Ever shut the line down? What happened? Everything broke loose. The plant manager, the plant superintendents, assistant superintendents, foremen, general foremen, everybody became unglued. We don’t get unglued here. lt’s a different world. It’s OK to shut the line down It’s OK to make a mistake. It’s OK to cause a problem because that’s an opportunity for us to change something and do something just a little better the next time round.”(2)

Once the problems have been corrected, the system can then be further stressed (perhaps by reducing the number of workers) and then rebalanced. The ideal is for the system to run with all stations oscillating between green and yellow. Extra resources are considered as wasteful as producing scrap.

There is an elegance to the idea that the system “equilibrates” or drives toward being evenly balanced. After years of observing waste in traditional plants, some people (workers as well as managers) are attracted to this vision of a smoothly functioning, rational, efficient system. The only problem is that human beings are the cogs in the system, not transistors, computers and motors.

Just-In-Time

Just-in-time (JIT) is a “demand-pull” approach to production. This means that an operation does not produce until its product is called for by the next operation. A material handler does not replace stock until the line operation signals that it needs more. A department does not produce until it is signalled from the following department.

Just-in-time requires drastic cuts in inventories, enabling savings on interest costs and warehousing. Quality control is easier because there are fewer parts in the pipeline. If a part supply runs two days ahead of use, when a problem is discovered, two days’ worth of parts will have to be repaired or discarded. But if parts production is running only minutes ahead of use, a problem can be corrected almost instantly.

But what about the traditional “just-in-case” reason for inventory-that one part of the production system is cushioned from problems in another part? Consider an assembly operation under JII If a station in the middle stops, downstream operations must quickly stop because they have no supply. Upstream operations must also stop because the finished products have no place to go. These seemingly negative features of JIT become positive under MBS. When a single point experiences trouble of any kind, management at all levels will immediately focus attention on the weak spot.

One possible way to deal with such emergencies would be to have available “flying squads” to come to the aid of workers having a problem. The characteristic response under management-by-stress is, of course, very different: production workers, team leaders and lowest-level management must solve the problem and catch up themselves. There is no external assistance until management is satisfied that extraordinary efforts and all the resources available to the team have been used.

Stress, rather than management directives, becomes the mechanism for coordinating different sections of the system. Ideally this means that top management needs only to make a few key decisions about the output required, and the system will automatically adjust to produce that output as efficiently and cheaply as possible.

But this can work only if the material handler, supplier department and supplier companies are all firmly committed to deliver “just-in-time” despite any obstacles. In order to maintain this commitment there ate penalties for failure. In the case of supplier companies, the penalties are financial.

In the case of individual workers, the penalties include attention and pressure from management, reduced perks, undesirable new assignments and possible discipline. That is why personal stress as well as system stress is required for MBS to keep running smoothly. A relaxed attitude — “I’m just doing my job; I don’t need to pay attention to anyone else’s” — makes the system inoperable.

Taylorism and Speedup

At the turn of the century Frederick W. Taylor championed scientific management,” symbolized by the time-and-motion study “expert” with the stop-watch. Since then management has sought ways to break jobs down into their smallest elements, examine each work element, determine the fastest method to perform an operation and instruct workers to use those methods. At the same time, unions have found that decent working conditions required limiting Taylorism.

Most of the current industrial relations literature portrays team production, including the versions that depend on management-by-stress, as a humanistic alternative to scientific management BusinessWeek editorializes:

“Such team-based systems, perfected by Japanese car makers, are alternatives to the ‘scientific management’ system, long used in Detroit, which treats employees as mere hands who must be told every move to make.”(3)

In fact the tendency is in the opposite direction — to specify every move a worker makes in far greater detail than ever before. Far from a repudiation of scientific management, management-by-stress intensifies Taylorism.(4)

While the jobs are, as advertised, designed by “teams,” most of the original members of these teams are engineers, supervisors and management-selected team leaders. They “chart” the jobs, that is, they break every job down to its individual acts, studying and timing each motion, adjusting the acts, and then shifting the work so that jobs are more or less equal.

The end result is a detailed written specification of how each team member should do each job. Jobs are “balanced” so that the difference between take time (number of seconds the car is at each work station) and the job-cycle time (number of seconds for a worker to complete all assigned operations) is as close to zero as possible.

As production increases and bugs are worked out, there are fewer and fewer changes made in job operations. Workers who are brought onto the team are expected to follow detailed procedures that have been worked over and over to eliminate free time and which specify how each motion is to be carried out. The team member is told exactly how many steps to take and what the left hand should be doing while the right hand is picking up the wrench.

While this may be logical from an engineering point of view, it can be hard on the human element. Short people may find it easier to do a job differently than tall people. Sometimes it is desirable to change the way one is doing a Job in the middle of the day to give some muscles a chance to relax and use others. The very rigidity of the system is illustrated by one Mazda team leader’s notion of flexibility: “We make allowances for people who are left-handed.”

But no matter how well workers learn their jobs, there is no such thing as maintaining a comfortable work pace. There is always room for kaizen, or continuous improvement. Whether through team meetings, quality circles or suggestion plans, if you don’t kaizen your own job someone else is likely to. The little influence workers do have over their jobs is that in effect they are organized to time-study themselves in a kind of super-Taylorism.

Yasuhiro Monden, who wrote the book NUMMI managers regard as their Bible, gives an example: management wants to reallocate jobs on a team because five workers are working every second out of a minute and the sixth, worker F, has 45 seconds of waiting time. This waiting time, says Monden,

should not be disposed of by distributing it equally among the six workers remaining on the line. If it were it would be simply hidden again, since each worker would slow down his work pace to accommodate his share of waiting time. Also, there would be resistance when it came time to revise the standard operations routine again. Instead a return to step 1 is necessary to see if there are further improvements that can be made in the line to eliminate the fractional operations left for F.”(5)

Thus changes in a job can never result in more breathing space for team members. Any improvements become the impetus for management to find even more ways to speed up the team. Good-bye, Mr. F.

Contrary to his current-day image, Frederick Taylor realized that workers do have minds and valuable knowledge. He insisted that the first duties under scientific management were:

“the deliberate gathering in on the part of those on the management side of all the great mass of traditional knowledge, which in the past has been in the heads of the workmen and in the physical skill and knack of the workmen which they have acquired through years of experience.”(6)

Like Taylor, MBS asks or even demands that workers make available their thoughts about the production process. Workers make suggestions, and management may or may not accept those suggestions. But once the suggestion is made the knowledge becomes part of management’s power to control every worker on the line.

Management-by-stress does differ from Taylorism in one regard. Taylor thought that he could discover production workers’ secret knowledge of the manufacturing process all at once, and that workers would then revert to being nothing but hired hands.

MBS managers, on the other hand, know that since workers continue to actually do the work, they continue to have knowledge about it that management observers do not enjoy — and therefore some power over production. One rule, then, is that a worker who believes he or she knows an easier or better way to do a job must share that knowledge with the team or group leader to get the group leader’s approval.

Absenteeism

Another key element in maintaining a taut system is the policy toward absenteeism. At NUMMI and Mazda, there are no extra workers hired as absentee replacements. A team consists of four to eight workers plus a team leader. The leader has no regular production job but performs an extensive list of assignments, some of which would be handled by the supervisor ma traditional plant.

The team leader keeps track of absenteeism and tardiness, distributes tools and gloves, deals with problems of parts supply and trains team members on new jobs. He or she helps out when a team member is having difficulty with a job and fills in when someone needs a bathroom break or must go to the repair area to correct a defect.

If a member is absent, the team leader has to do that person’s job. Then if team members need relief or help they must depend on the group leader, who supervises two to four teams, either to fill in directly on the job or to assign a member from another team to help out.

Thus other team members find it harder to get relief when they need it and tend to resent the absentee. Several workers interviewed at NUMMI commented that they would like to have people who were absent too much removed from their group.

Peer pressure can be a powerful force in the workplace. Most of us have strong needs to be accepted and respected by the people we regard as our peers. In a factory where the discipline of the line increases alienation and a sense of powerlessness, the threat of losing this acceptance and respect is even more compelling. The harder the job, the more workers depend on one another for even small instances of informal cooperation: moments of relief, humor, psychological support, watching your back, physical assistance and information. Management well understands the power of peer pressure and directs it to its own ends.

Stopping the Line

“Workers can stop the line.” This promise is the single feature that has come to symbolize the difference between MBS and “the old way of doing things.” The companies present this power as the foundation of their policy of respect for the workers’ humanity. Monden says, “It is not a conveyor that operates men, it is men that operate a conveyor.”(7)

The ability to stop the line is powerfully attractive. In the Big Three (Chrysler, Ford and GM), a worker did not stop the line unless someone was dying. It didn’t matter if a worker couldn’t keep up or if scrap was going through. You tried to get the foreman’s attention, and he could decide whether to stop the line (rarely) or leave the problem to be repaired further on (usually). Stopping the line without a really good cause meant discipline.

Under MBS the right to stop the line is supposed to substitute for the cumbersome system used in traditional plants to establish work standards. In traditional plants, the company industrial engineers or time-study experts determine the particular operations and time allotments for each job. The union contract prohibits management from setting standards by using exceptionally young, strong, nimble or well-trained workers.

Work standards, once established, cannot be changed arbitrarily. The union has the right to grieve work standards, and they are among the few issues that can be struck over during the life of the contract. The contract language states that management cannot discipline workers for failing to keep up as Jong as they are working at a “normal pace.”

“But with the stop cord, why have all these bureaucratic procedures?” the argument goes. There is no need for contractual arrangements to change the number of tasks on a job if you have a system that trusts the worker. If the worker is making a genuine attempt, but cannot keep up, he just pulls the stop cord. There is – supposedly — no penalty.

The NUMMI contract specifically allows for easy change of production standards by the group leader. The union is not involved in the initial setting of such standards. They are not grievable but use a different procedure in which a worker can appeal to a committee composed of two management and two union representatives.

During the trial-build period, “the cord” seems to work for everyone. It helps workers get assistance when problems come up, and it helps keep quality high even through all the problems of establishing a new line. It aids management in identifying problems so they can be quickly resolved.

However, once the bugs are worked out and the line is speeded up, it becomes harder and harder to keep up all the time. Once the standardized work-so painstakingly charted, refined, and recharted — has been in operation for a while, management assumes any problem is the fault of the worker, who has the burden of proof to show otherwise. NUMMI rules provide for warnings, suspensions and firing for “failure to maintain satisfactory production levels based on Company performance standards.” Stopping the line means the chimes and lights of the and on board immediately identify who is not keeping up.

There is good reason for this pressure. An idle assembly line represents enormous costs in equipment and labor. Just-in-time can multiply these costs many times over. Thus once the line is up to full operating speed, supervisors do become “unglued” when the line actually stops.

A worker who is having trouble keeping up has four choices, none of them good:

1. He or she can stop the line. This is likely to attract immediate and unhappy attention from the group leader.

2. He or she can work “into the hole”-farther down the line from his assigned position — to try to catch up. But it’s hard to catch up when you’re already working at maximum speed. And, like everything else in management-by-stress, he system uses peer pressure against working in the hole. Because jobs are so tightly charted, a worker who keeps working into another person’s area may throw off that worker’s pacing.

3. He or she can signal the team leader for help. But if the team leader has to spend all of her time helping one worker to prevent the line from stopping, then that leader is not available for other workers who might need to go to medical or need temporary assistance-creating peer pressure again.

4. He or she can let the job go through uncompleted. Again the system works against that. Workers downstream are certain to pull the cord if they spot an incomplete job from a previous station-they can get a breather at no cost to themselves. Attention is once again drawn to the unfortunate worker who has fallen behind-and has compounded the error by letting unfinished work go through.

The only solution, therefore, is to keep up with the line speed with no errors, whatever it takes. Some NUMMI workers use part of their breaks or come in early to “build stock.” Thus NUMMI’s high productivity figures are partly the result of effectively forcing workers to work overtime for free.

Others work “in the hole” in hopes of catching up later. A Mazda worker describes the Catch 22 in which a co-worker found herself:

“She had a hard time one day and pulled the stop cord several times. The next day management literally focussed attention on her. Several management officials observed and they set up a video camera to record her work. She found herself working further into the hole. She worked into the hole too far and fell off the end of the [two-foot] platform and injured her ankle. They told her it was her fault-she didn’t pull the stop cord when she fell behind.”

The new “right” to stop the line is as illusory as the end of Taylorism.

The Multifunctional Worker

A principle of just-in-time is that a worker never produces for stock even if there is nothing else to do. Extra stock is waste, and besides, there is no place for it to be stored and no procedure to handle it. It is better for workers and machines to stand idle than to produce in excess of what is immediately needed.

Yet management cannot allow idle time to be part of the system. Idle time reduces labor productivity. The system is designed so that any idle time is a visual indication that something needs to be adjusted. A worker who can shave a few seconds from his or her cycle time should not take the initiative to help out fellow workers or find some task to be done. It is better to stand still so that management can see that there is some free time that can be assigned a regular task.

If JIT forbids producing in advance, but idle time cannot be tolerated, the only way that the system can work is for production to be organized so that jobs can be shifted and adjusted easily without disrupting the production process itself. This is particularly important in the auto industry where both the number of vehicles to be built and the model mix can vary considerably and quickly. The high responsiveness of MBS plants is a major contribution to their high productivity.

This management flexibility to easily redistribute tasks requires that: 1) Tasks must be broken down into the mallest units possible; 2) the skill level for each task must be as low as possible; and 3) workers must be able and willing to do any task assigned.

Management calls this last “multiskilling,” a misleading term. The abilities required in performing several related jobs of very short duration are manual dexterity, physical stamina and the ability to follow instructions precisely. Even here management is careful to design jobs not to require exceptional amounts of any of these, because they want to be able to assign workers interchangeably. These are not “skills” in the usual sense of requiring training and specialized knowledge. The essence of “multiskilling” is actually the lack of resistance, on the part of the union or the individual worker, to management reassigning jobs whenever it wishes, for whatever reason.

Outsourcing

The UAW-NUMMI contract specifies that the company will take “affirmative measures,” including “assigning previously subcontracted work to bargaining unit employees capable of performing this work,” before laying off any employees. This arrangement, a variant of the system used in Japan, is being interpreted in this way: as long as the company guarantees the jobs of all regular workers, the union will not object to outside contracting (employees of an outside firm do work in the plant, such as cleaning or repairs) or outsourcing (parts are bought from outside firms). Both are extensive at NUMMI and Mazda.(8)

The deal seems to provide job security, but in reality the job security is less than if the work were not outsourced and the plant had traditional seniority protections during layoffs. Say the MBS assembly plant has. 1,000 workers, and there are 200 workers working at a supplier company making seat cushions. If sales decline, which would normally cause the layoff of, say, 200 assembly workers, the assembly plant is committed to bringing the seat-cushion work into the plant, in order to keep those 200 assembly workers on the job. The 200 cushion workers at the supplier company would all Jose their jobs, in favor of the assembly workers.

Now let us look at the same situation in a traditional assembly plant of 1,200 workers. This plant includes a cushion room because the union was able to prevent the company from outsourcing the cushion work. When sales decline, the lowest 200 or so workers are laid off, plant-wide. There are still 1,000 workers on the job and 200 on the street-but the laid-off workers have recall rights to their union plant.

The 1,000 MBS workers, who supposedly received job security in exchange for outsourcing, have not gained any more job security in comparison with the 1,000 highest-seniority workers in the traditional plant Thus the job security that MBS provides is of the “see no evil” variety. Management divides workers into two tiers-those at the main plant, protected by the union and the paternalism of the company, and those at the supplier plants, usually non-union, who have no protection from layoffs and no supplementary unemployment benefits as the unionized workers do.

Union endorsement of this kind of arrangement gives substance to the charge that unions attempt to protect the elite few at the expense of poorer, less protected, workers-who also turn out to be disproportionately women and minorities. Such a policy also makes it all the more difficult for unions to organize the increasing number of non-union supplier plants.

Use of New Technology

NUMMI management points with pride to the fact that it has succeeded without the most advanced technology. This has led many, both in management and in the union movement, to see in NUMMI an alternative to the high-tech approach to productivity.

Even so, while NUMMI does not represent the cutting edge in new technology, it is not far behind. Mazda is even more modern. In 1986 Nissan management claimed that its Smyrna, Tennessee, facility had more robots than any other U.S. assembly plant Honda has announced elaborate plans to install a new system in its Ohio plant, which is supposed to automate 80 percent of vehicle assembly and triple productivity.(9)

Management-by-stress systems have a coherent approach to technology. Automation is not done for its own sake. Labor is divided into two kinds. On the one hand is “value-added” labor. This is direct work on, or assembly of, materials, which increases the value of the product. On the other hand, almost everything else is “non-value added.” This includes material transfer and handling, most inspection, repairs, maintenance and cleaning. There is a heavy emphasis on reducing non-value added labor.

Any technological change that replaces a production worker with an indirect “non-value added” job is rejected. For example, a machine that replaces one production worker but requires an additional electrician to be in the area is a bad idea. And any automation must increase management flexibility, not decrease it. The approach can be seen in Monden’s warning:

“Even if the introduction of an automatic machine reduces manpower by 0.9 persons, it cannot actually reduce the number of workers on the line unless the remaining 0.1 person … can be eliminated. The introduction of [automation] may actually eliminate the ability to reduce the number of workers a matter of some concern, since it is always essential to reduce the workforce, especially when demand decreases.”(10)

The emphasis in MBS plants, then, is on small au tomation that improves the functioning of the system — jikoda or “autonomation,” as it is called at NUMMI and Mazda — rather than on sweeping changes that transform basic manufacturing methods.

And What About Teams?

In management and union circles, as well as the popular press, the system we have described as management-by-stress is referred to as the “team concept.” Yet we have made few references to the functioning of teams. “Team” is simply the name management gives to its administrative units. If we substituted “supervisor’s sub-group” for team, understanding of management-by-stress would not suffer at all.

In MBS plants teams do sometimes meet and discuss problems. When the lines move slowly team members can and do help each other out But this is most likely during initial start-up. When the system is running at regular production speed, team meetings tend to drop in frequency. Some workers at NUMMI say that months pass between team meetings. In other cases team meetings are nothing more than shape-up sessions where quality or overtime information is transmitted to the workers or a supervisor announces changes in assignments.

When management talks to itself about what makes the system work, teams, in the sense of teamwork or team meetings, are rarely mentioned. In his description of Toyota, Monden does not use the term “team” at all. He does, however, devote a few pages to the description of the mandatory Quality Control Circles made up of” a foreman and his subordinate workers.”

The Union

Management-by-stress is truly a lean and mean system. In tightly connecting all operations, consciously seeking to strip out all protections and cushions, and making all parts of the system almost instantly responsive to change, management-by-stress becomes a highly efficient system for carrying out management policy.

But these same strengths also create a potential Achilles’ heel for management. Unions are potentially more dangerous. If workers collectively take certain actions the system becomes extremely vulnerable. One industry publication contains the warning that with just-in-time, “unions have a lot more power than they did before.”(11) The action of workers in one department can immediately affect the entire operation, both upstream and downstream.

The key word is “collectively.” The system easily handles individuals and small groups who resist But suppose everyone starts pressing the stop button in an organized campaign to let management know that the line speed is too fast or that they need absentee replacements. It is no longer a case of isolated troublemakers, and management can no longer contain the problem. An organized slowdown, sickout or job action by a sizable minority in a department can disrupt the entire plant.

Thus in MBS plants the union’s relationship with management must be settled from the beginning. MBS cannot operate for long with a union that fights stressful jobs and organizes its members to challenge management on the shop floor: For MBS managers there are two alternatives: either prevent unionization in the first place, or keep a subdued union that helps prevent collective action and defuses any sense of solidarity and militancy on the shop floor.

Personal Stress

Continued long-term stress over which the individual has no control, when high hormone levels and other physiological changes become the body’s normal state, has well-established links to heart disease, asthma, ulcers, diabetes, depression, drug abuse and alcoholism. Research on animals has shown a direct relationship between “inescapable stress” and suppression of the immune system cells involved in fighting cancer.(12) The primary hormone released in response to stress, cortisol, suppresses the immune function generally and kills certain brain cells.(13)

Chronic stress contributes to accidents and family problems. High continued stress levels can be particularly dangerous because a person can believe he or she has “gotten used to” stressful environments even while the body maintains its high reaction to stress.(14)

What kind of job generates the greatest stress? Researchers have found that a combination of high job demand and low job control produces the maximum stress.(15) Contrary to the popular belief that stress is the burden of top executives, studies have shown that the most stressful jobs include inspector of manufactured products, material handler, public-relations worker, laboratory technician, machinist, laborer; mechanic and structural-metal craftperson.(16)

It is not just the hard work itself that creates stress in management-by-stress plants. For all the talk about their new job security, interviews with NUMMI workers reveal fear of the plant closing is uppermost in their minds and often justifies everything that happens in the plant The fact that the system is so inflexible when it comes to workers’ personal needs also generates stress: What kind of job could I do in this plant if I were injured? How do I get time off for a personal problem?

Respect and Dignity

Toyota and NUMMI claim that dignity and respect for the individual are key to their management theory. Toyota managers describe the system as the “respect-for-human” system. Evidence of this respect certainly exists. Visitors to the NUMMI plant are struck by the plant’s atmosphere. Workers are addressed courteously. The plant is clean and well lit and seems like a nice place to work.

At the same time operation of the plant indicates a very peculiar notion of humanity-that human fulfillment is achieved only by striving for management’s goals. Monden displays this management mentality:

“Reductions in the workforce brought about by workshop improvements may seem to be antagonistic to the worker’s human dignity since they take up the slack created by waiting time and wasted action. However, allowing the worker to take it easy or giving him high wages does not necessarily provide him an opportunity to realize his worth. On the contrary, that end can be better served by providing the worker with a sense that his work is worthwhile and allowing him to work with his superior and his comrades to solve problems they encounter.”(17)

And a Mazda manual concurs: “If you are standing in front of your machine doing nothing, you yourself are not gaining respect as a human being.”(18)

This view of dignity may be convincing to the managerial mind. But unions have different goals and need a different definition of human dignity.

In any case, MBS systems are being hailed-by management and union alike-not because of their effect on dignity but because of their impact on the bottom line-productivity and profit. MBS plants meet these goals, but at great cost to worker autonomy and union power.

Notes

- We have drawn heavily on the views of Toyota management as described in: Yasuhiro Monden, Toyota Production System: Practical Approach to Production Management (Industrial Engineering and Management Press, 1983). We have also used documents and video tapes developed by General Motors for internal management use, as well as training materials used at NUMMI and Mazda. Finally, and most importantly, we have looked at the day-to-day operation of NUMMI and Mazda by interviewing workers from both those plants.

back to text - General Motors Technical Liaison Office, This is NUMMI, video tape for GM managers, 1985.

back to text - Business Week, Aug. 31, 1987.

back to text - Two excellent pieces with analyses similar to that presented here are Knuth Dohse, Ulrich Jurgens, and Thomas Malsch, “From ‘Fordism’ to ‘Toyotism’? The Social Organization of the Labor Process in the Japanese Automobile Industry,” Politics and Society, vol.14, no. 2 (1985); and Peter J. Turnbull, “The Limits of Japanisation-Just-In-Time, Labor Relations and the UK Automotive Industry,” New Technology, Work, and Employment, vol. 3, no. 2 (Autumn 1988).

back to text - Monden, 122.

back to text - “Testimony to the House of Representatives Committee, 1912” in Frederick Taylor, Scientific Management (New York and London: Harper and Brothers, 1917).

back to text - Y. Sugimori, K Kusunoki, F. Cho, S. Uchikawa, “Toyota Production System and Kanban System” (1977), reprinted in Monden 211.

back to text - For international trends in outsourcmg see Michael A. Cusumano, TheJapanese Automnbile Industry: Technology & Management at Nissan & Toyota (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985) 189.

back to text - Detroit Free Press, Nov. 2, 1986, Dec. 30, 1986.

back to text - Monden, 124.

back to text - Manufacturing Week, Aug. 3, 1987.

back to text - L.S. Sklar and H. Anisman, “Stress and Coping Factors Influence Tumor Growth,” Science (Aug. 3, 1979): 513-15.

back to text - R. Sapolsky, “Glucocorticoids and Hippocampal Degeneration,” Abs.,69th Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society, Indianapolis, June 1987: 9.

back to text - Communications Workers of America, Occupational Stress: The Hamrd and the Challenge, Instructor’s Manual, 1986. Also, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Stress Management in Work Settings, May 1987.

back to text - “Jobs Where Stress is Most Severe: Interviews with Robert Karasek,” U.S. News and World Report, Sept 5,1983. Also, Lee Schore, Occupational Stress: A Union Based Approach (Oakland, California: Institute for Labor and Mental Health). Also, John Holt, “Occupational Stress,” in Leo Goldberger and Shlomo Breznitz, Handbook of Stress (New York: The Free Press, 1982).

back to text - Psychology Today, January 1979.

back to text - Monden, 131.

back to text - Kaizen Simulation, Mazda Motor Manufacturing (USA) Corporation, no date (about 1986), VI-2.

back to text

March-April 1989, ATC 19