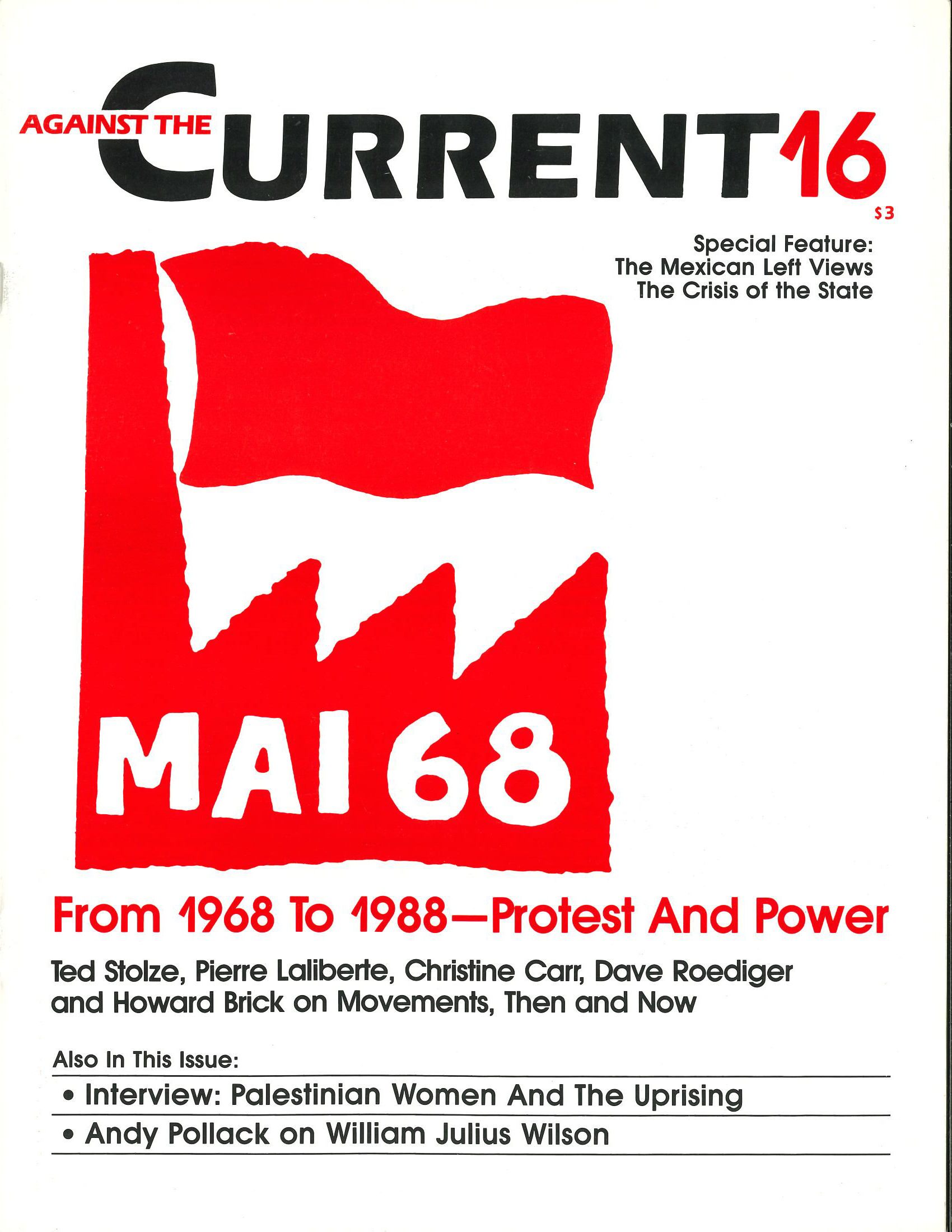

Against the Current No. 16, September-October 1988

-

The Rainbow and the Democrats After Atlanta

— The Editors -

Palestinian Women: Heart of the Intifadeh

— Johanna Brenner interviews Palestinian activist -

Critique of William J. Wilson: The Ignored Significance of Class

— Andy Pollack -

Ramdom Shots: Libs, Labs and Lawyers

— R.F. Kampfer - From 1968 to 1988

-

1968 and Democracy from Below

— Ted Stolze -

Lessons from the Campus Occupation

— Pierre Laliberté - Summary of Occupiers' Demands

-

USC Women Demand an Autonomous Center

— Christine Carr -

Something Old, Something New

— Dave Roediger -

The Participatory Years

— Howard Brick - Mexico: The Crisis, the Elections, the Left

-

Mexico: The One-Party State Faces a Deep Political Crisis

— The Editors -

The Need for a Revolutionary Alternative

— Manuel Aguilar Mora -

The New Stage and the Democratic Current

— Arturo Anguiano -

Call for a Movement to Socialism

— Adolfo Gilly and 90 others - Dialogue

-

Radical Religion--A Non-Response

— Paul Buhle -

Everyone Knows This Is Nowhere

— Justin Schwartz - An Appreciation

-

Raymond Williams, 1921-1988

— Kenton Worchester

Manuel Aguilar Mora

THE HISTORIC MOMENT at first seems to be diluted by the details of everyday life. But it is these daily events which, added one after another, make up the life of a people. Turned into sequences, this ordinary life becomes the history of a people in their various social, economic, political and artistic expressions.

An historic event is not comparable to these details, which also nourish history. An historic moment is not merely one fact of history, although it resembles such an event. The historic moment is really a condensation, an extraordinary synthesis. Although such moments are explained and proceeded logically through daily life, historic events are key movements. They bring periods to a dose, they open eras, they forge new paths in the trajectory of a people.

October 2, 1968 in Mexico was one such “historic” event–the massacre of the students at Tlatelolco. Of course the political expression of this violent dash was interpreted differently by the country’s various social classes. Nevertheless, all people understood that day signaled an end to the historic period of a one-party state completely dominated by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI).

Hegel observed that history repeats itself. Mexico is no exception. The twentieth anniversary of the onset of the student movement (July 26, 1968) coincides almost to the day with the presidential elections of 1988 (July 6). The earlier date marks another decisive movement in the Mexican people’s quest for democracy.

The past twenty years have been one of a gradual PRI-ist decay. But the stagnation and sclerosis of the PRI government gripped entire segments of society with an ideological and political cynicism that in tum served to close even more avenues to social progress. Yet alongside the disillusion and apathy were glimpses of hope. From this prolonged agony in the system of domination there began an arduous transition from a conquered age–on the social, political and economic level–to a new but ambiguous period. These twenty years paved the way for the electoral clash of July 6, setting the stage for the open political defeat of PRI-ist hegemony on a national scale. The political tremor of July 6th revealed the depth of the decay-and it was announced publicly by the majority of forces present on the Mexican scene.

The long trajectory of PRI-ist power, defined in classic Marxist terms as Mexican Bonapartism,*has been the object of scrutiny, both internally and internationally. For over sixty years journalists, politicians and writers have scrutinized the unique system of domination that emerged out of the Mexican Revolution. Protagonists have also given their own testimony. Despite the difference in interpretation, all are fascinated by a oneparty state that is as stable and long-lasting as ours has been.

Following the far-reaching Cardenas reforms of the 1930s, the strength of the PRI-ist system proved untouchable. Nearly three decades witnessed the flourishing of institutions that tied the masses to the regime. These masses were led by and contained within the apparatus of the unions and other mass organizations linked with the PRI. These were also the consolidating years of charrism, the ultimate form through which union officials served the PRI-ist government with servility.

Economically the national capitalists lived the life of fat cows. They were favored by the high indices of economic growth and low inflation, a stability of exchange rates and expansion of the internal market, and guaranteed low prices for agricultural products. In relation to the investment and reproduction of capital, wages were minimal. In short, there were the most appropriate conditions for the rise of a powerful and “bullish” capitalism. Politically, the PRI was able to posit itself as the sole party capable of governing.

The Bonapartist system established such deep roots that it far outlasted previous experiences of its type. After the assassination of Obregon and the political death of Calles, it was no longer characterized by a specific leader (caudillo). Lazaro Cardenas molded this Bonapartist system into a presidential structure and converted it into an institutionalized system that would create, every six years, an ad hoc caudillo from the clay produced from the bureaucratic human materials of the official governmental party.

Consequently we see the emergence of such golden mediocrity as the presidents of the republic who followed Cardenas. All of them were men of little or no real political charisma. Their notable lack of any leadership ability was “balanced” by their enormous capacity to manipulate and control.

Bureaucratic norms and routinism imposed themselves upon these Bonapartist regimes, drawing out and reinforcing reactionary elements. Whatever so-called revolutionary attributes from which the PRI government drew its legitimacy quickly paled with the incorporation of administrators and technicians who stamped the regime with a notably bourgeois character.

A Miracle for Capital

During the 1940s and 1950s a period of investment and development created the basis for a “Mexican Miracle.” The bourgeoisie grew rapidly along with the accumulation of capital. In the process industrial belts developed in the urban areas (the states of Mexico, Monterrey, Guadalope and Pueblas), in northern border cities and in the oil regions of Coatzacoalcos and La Laguna. The grain farmers of Sonora and Sinaloa were strengthened by the far-reaching hydraulic works developed by the government.

But the migration was not contained within Mexico’s borders. The post-World War II boom in the United States generated a need for labor, especially in the large cities of California and Texas. Millions of Mexicans crossed the border to find jobs. In fact it was this northern, border region of Mexico which became the most dynamic area of demographic and economic growth–cities such as Ciudad Juarez, Tijuana and Mexicali.

Originally North American imperialism was suspicious and fearful of a revolutionary threat coming from its southern border, but by 1940 those fears began to be calmed. The collaboration between the U.S. and Mexican governments developed on the basis of their common interests. That is, the interests of the White House and the ever more palpable reactionary features of the Mexican government were reflected in their developing relationship. Nevertheless the Mexican government continued its nationalist phraseology here and there (with an occasional revolutionary flash left over from the 1910-19 period) and occasionally real differences between the two governments were openly expressed, especially in foreign relations.

Washington realized that a special political relationship with its southern neighbor was clearly to its advantage. The U.S. could keep its key border with Mexico secure, peaceful and completely favorable to its overall global strategy. Since then, the presidents of the two countries have met periodically. Despite divergence, the basic cooperative framework that links the two governments has not been threatened. Consequently the PRI and its government have been pulled increasingly toward supporting imperialism.

The Mexican capitalist economy developed out of the strength of a world system that is undergoing profound technological transformation. A number of fa tors are changing the situation: the increase in inter-imperialist competition, the decline of U.S. hegemony, the rise of a growing Japanese capitalism in the Pacific, the efforts of the European capitalists to avoid being relegated to the fringe of the world market, the accelerated internationalization of productive methods and processes initiated by large transnational corporations, the generalized globalization of finance and the corresponding consumer indebtedness as well as the internationalization of accelerated arms production.

These are some of the world processes which together have made of this present moment the most synchronized hour in the history of humanity. Continents are closely interlinked by communication and all countries are more closely bound to each other. Thus Mexico is becoming a country deeply linked to late capitalism. Itis in this context that Mexico’s nationalized companies have had to face the brunt of the inevitable inflation and fiscal crisis.

Additionally, 1968–the year in which this boom period died its political death-Mexico suffered the shock of government repression against the student movement October 2, 1968 opened a slow but irreversible change in consciousness that undermined the legitimacy of the PRI in ever-widening sectors of the population.

The student movement represented an impressive revitalization of the revolutionary tradition. Many students took Fidel Castro and Che Guevara as their models. They were anxious not only to study the processes by which revolutions occur, but to put into practice the theory and tactics of those leaders. The Chinese Cultural Revolution also found university adherents.

The university community saw the rise of dynamic and radical groups. In the course of a far-reaching ideological debate the Mexican left largely shook itself free from Stalinist obscurantism. Of course this advanced political debate was occurring at the same time on an international level, as anti- imperialist and revolutionary battles of colossal dimensions were being waged.

The battle of the Vietnamese people against Yankee imperialism was a determining conflict of that period. But in Latin America, there was also a renewal unleashed by the Cuban Revolution. Many of the revolutionary groups formed in that period were channeled to guerilla struggles. A similar process was unleashed in Africa, where struggle for national liberation gave substance to a movement of international solidarity. And everywhere students were in the vanguard.

Che Guevara was the heroic figure who symbolized in his genial, bold and steadfast personality the aspirations of a generation. This enormous revolutionary awakening was also reflected in the recovery and recreation of Marxist theories. Authors who had been buried under years of Stalinist dogmatism were read. These including the writings of the young George Lukacs, of Rosa Luxemburg, Antonio Gramsci and, especially prominent, the writings of Leon Trotsky. Trotsky’s message was understood and appreciated by a youth sensitive to the struggle against bureaucracy and to the international dimension of a socialist perspective.

The National Council of Strikes and the Student Movement Committees for Struggle nourished themselves on these revolutionary trends. In their turn, the events of 1968 vastly renewed the panorama of left organizations. New parties emerged, those already in existence were strengthened-but several organizations unable to adjust to the new situation were swept away. The democratic and independent features established by the student movement were to influence and mold the popular mobilizations of the ’70s.

The twenty years that have passed since 1969 seem today a long period of time, measured in a quite leisurely pace. Two decades represent the difference between youth and maturity in the life of a person, yet they are mere moments in the life of the people of Mexico. However, the twenty years also represent the politically maturation of the Mexican people in their search for economic and social justice.

The political crisis first manifest in 1968 has now deepened into an economic crisis of major proportion. By the early 1980s the oil boom could no longer mask the weight of the crisis. And during its last year in office the Jose Lopez Portillo government (1776-82) attempted to stop the multimillion dollar flight of capital by nationalizing the banking system.

Toward the Fall of a System

The election of July 6 marks the first act of the concrete, real and undeniable fall of this unique system of domination. The fall of the PRI was to be expected, but it will not proceed along a straight line. Nonetheless at each turn, the dilemmas that underpin the system will be revealed on a larger scale. This crisis of the PRI will also pose a real challenge to revolutionary political imagination. It is precisely such moments which, if intelligently and audaciously utilized by the revolutionary movement, can be the preparatory period for a social transformation of the system. The fall of the ancient regime contains a possibility of revolution.

1. Discontent and Economic Situation

Miguel de la Madrid’s presidential term began in 1982 under the most unfavorable conditions. The foreign debt reached the unbelievable figure of $100 million, with interest payments alone consuming more than half of the federal budget. Stagnation gripped industry and agriculture. Unemployment swelled to 15- 40% of the economically-active population.

Meanwhile the ruthlessly “rational” plan imposed by President de la Madrid has failed to achieve its principal objective of lowering inflation, which for the first time in decades has reached the three-digit figure. This austerity plan has stripped the country of its nationalized firms and imposed cutbacks on public services, especially in the areas of education and social welfare. Real income has been cut in half.

The impoverished masses sought ways out of their ever-worsening situation, particularly through rein forcing the trend of migration from the rural areas to the city. Today metropolitan Mexico City approaches a population of twenty million. Conditions bordering on famine in the countryside have also increased the number of migrant workers forced to find work in the United States.

De la Madrid’s team-with its key lieutenant, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, Secretary of the Budget and Planning–enacted an austerity program completely tailored to the interests of the large capitalists, both at home and abroad. Central to the plan has been the promotion of exports through a productive and efficient industry endowed with “competitive” prices. This factor, combined with rising inflation, precipitated the fall of the peso. The exchange rate of the peso in relation to the dollar rose from 46 pesos in February 1982 to 2,300 pesos in August 1988.

Capital flight has been estimated at $40 billion, or approximately half of the foreign debt. In order to attract capital, the country has been opened up to foreign capital. This has facilitated the maximum investment opportunities at extremely low wages. Today the average Mexican wage is lower than the average wage of the worker in Hong Kong, Taiwan and South Korea. While wages represented 57% of the gross national product in 1982, by 1987 that percentage had been whittled down to26%.

An economic policy so damaging to the interests of working people could not have been imposed without the active and abject participation of the official union bureaucrats, the sadly-celebrated charros [literally, the bosses). Right from the very beginning of De la Madrid’s term, there has been a close collaboration. Fidel Velazquez, who heads the Workers Confederation of Mexico (CTM), was key to the implementation of the plan. During 1983-84 some unions tied to the bureaucracy, principally the CETEMISTA, attempted to partially reverse the decline in wages. Some strikes occurred, but in the end the capitulation of the charros set the stage for the frightening last three years, during which the decline continued.

In December, 1987-faced with a situation fraught with danger for the PRI government-De la Madrid imposed the Pact of Economic Solidarity. A combat plan designed to reverse an economy on the precipice of hyperinflation; it slowed inflation but only at the cost of setting into motion an economic recession. Once again the pact could not have been implemented without the decisive role of the charros.

This pact was the mechanism by which the PRI removed the threat of inflation from the political agenda. Nonetheless by June, inflation had climbed by 42%. Clearly the PRI was correct in its evaluation-had the inflation rate continued unabated, there would have unleashed an even harsher reaction of popular discontent than the July 6th rout of the PRI.

The De la Madrid administration was shamelessly linked to national and international capitalism. Especially favored were the most powerful groups associated with international banking and export Their economic line of completely opening the Mexican economy to international exploitation was achieved at the detriment of the capitalists connected with the domestic market From this point of view, the traditional pendulum of PRI-ist policy stretched further to the extreme right and upset the weights and counterweights that have characterized Mexican Bonapartism.

2. Discontent and Political Struggle

Despite the deep-rooted strength of the Mexican system, the capitalist crisis shook and destroyed the political edifice of PRI-ism. But the strong cogs of the apparatus–the bureaucratic bastions of the charros–held more or less firm as they abjectly carried out the dictates of the PRI. Since the central bastions of the working class were anchored to the charros, the popular struggle against austerity began, during the1983-84 period, with those working-class sectors aligned with independent and leftist forces. These work stoppages had a modest impact.

It was the campesino struggles, without a doubt, that had the highest level of mass resistance against the government Their principal shortcoming was an absence of coordination that could enable them to synchronize their actions on a national scale.

The earthquake of September 19, 1985–primarily affecting Mexico City-triggered the first great spontaneous act of popular protest. The rescue operations were carried out by the spontaneous self-organization of the city’s population. Millions of citizens, particularly the youth, were aware of a governmental inertia bordering on utter irresponsibility. The army left its barracks not so much to mobilize in the rescue of the victims and the rebuilding of the city but to guard against pillage and protect private property.

The clumsy and insipid head of Mexico City, Regent Ramon Aguirre, symbolized the official paralysis in the face of the disaster. Consequently, in the most populous center of the nation, a city decisive in setting the nation’s direction, the government lost credibility. It was as if the emperor had no clothes.

The neighborhoods in Mexico City were particularly affected by the havoc of the earthquake. And it was there where the struggle for low-cost housing [a constitutionally-guaranteed right) was born. Coupled with it was the demand against pollution.

Throughout 1986 and ’87 a number of demonstrations signaled a clear change in the mood of the masses. In retrospect, they prefigured the action the Mexican people took on July 6, 1988.

In the first place, the students of UNAM, the foremost university of Mexico (400,000 students), began a fight against the austerity plans unleashed by the rector. This led to the creation of the University Student Council (CEU) and to mass mobilizations of hundreds of thousands. A 1987 university strike, led by the CEU, gained a victory. The parallel with the university events of 1968 did not go unnoticed.

Spurred by that example, the electricians union also carried out a strike, which shook the traditional union routinism that has characterized working-class organization in Mexico.

At the end of 1987, when all of the political forces prepared themselves to enter the electoral fight, all indications pointed unerringly toward a major confrontation between the PRI and a new combative protagonist comprising workers, peasants, students, women and other social forces.

The PRI had lost significant ground in previous elections. All the opposition-from the bourgeois to the revolutionary and reformist parties-were making solid, and in some cases spectacular, advances. In 1983, the PRI for the first time lost the election in two out of the ten most important cities in the country. These included Ciudad Juarez–the most populous of the cities that border the United States-and Chihuahua. PAN, a bourgeois party with a liberal orientation, proved to be the principal opposition force.

The1986 gubernatorial elections in the state of Chihuahua foreshadowed what was to come on a national scale two years later when the PRI’s fraudulent operation robbed the PAN of its victory, and the PRI-ist candidate, Fernando Baeza, the clear loser, was installed. Everything seemed to indicate that the PAN would become the sole beneficiary of the national anti-PRI sentiment Yet as strong as the interbourgeois fight seemed, it was not of sufficient magnitude to predict a PRI-ist defeat in 1988.

De la Madrid tenaciously pursued a course which would avoid the closing moments of his administration ending in a confrontation with a group of capitalists–as was the case with his predecessors, Luis Echeverria and Lopez Portillo. Instead he upheld the policy of dismantling the nationalized state properties, putting up for sale Mexico’s largest copper mine at Cananea, liquidating the Monterrey foundry, the largest and oldest in all of Latin America, and declaring Aeromexico airlines bankrupt.

The president of the Council of Economic Enterprise (CEE), Augustin Legorreta, praised the work of the de la Madrid government However so much dismantling occurred that Legorreta spoke a little too frankly, admitting, “Mexico’s economy is managed by about three hundred of us big business leaders.”

For the regime, the political cost of austerity was insignificant Yet this action dearly represented a drastic tum away from traditional PRI policy. And dearly de la Madrid’s PRI successor would receive fewer votes than de la Madrid had been credited with in1982. But the PRI took for granted that Salinas would emerge president, as did his predecessors. Seemingly, the routine would recycle itself once again.

3. The Crisis of the PRI

In August 1986, a group of notable PRI-ists constituted themselves as the Democratic Current within the PRI. Among the most important were:

• Cuauhtemoc Cardenas, ex-governor of Michoacan, officeholder in various administrations and son of Lazaro Cardenas;

• Porfirio Munoz Ledo, secretary-of-state for two administrations and president of the PRI from 1975-76;

• Rodolfo Gonzalez Guevara, Lopez Portillo’s under-secretary;

• Ifigenia Martinez, PRI deputy and officeholder.

When the Democratic Current emerged not even the founders themselves could have conceived the pivotal destiny of this dissident PRI-ist group. It, in effect, announced a deepening crisis of the PRI, one that would end in a rupture.

The goal of the Democratic Current was plain and simple. They sought to make room in the presidential process for the PRl-ist groups most sensitive to the consequence of de la Madrid’s curse. They kept an utterly orthodox stance within the PRI-ist ideological fram work, reiterating the traditional reformist principles of the party. That is, they never declared an open preference for any of the three strong contenders for the nomination, but sought for a more democratic procedure than the president picking his successor. Implicitly the Democratic Current rejected Salinas as the presidential candidate, and later they proposed Cardenas’ name as a fourth nominee.

But once Salinas had been selected by the only elector in the PRI who counted-President de la Madrid–the PRI closed ranks and did not accept the nomination of Cuauhtemoc Cardenas. The mere decision of the Democratic Current to enroll Cardenas as a PRI-ist candidate provoked the protective deployment of the pol ice around the PRI building. This act revealed the absolutely impenetrable path such currents face inside the PRI.

The Democratic Current left the PRI, but not even all its founders followed Cardenas. Nonetheless, the fissure occurred. It did not take place in the stronghold of the apparatus–within the union officialdom–but rather on the edge where Cardenas headed a minority faction of dissidents.

In a Mexico thirsting for change-yet still being politically steered by a bourgeois nationalist current–and in the absence of a decisive proletarian mobilization, the son of the most influential president of the twentieth century was not going to be shoved aside so easily.

In fact, the Cardenas campaign became the most impressive electoral mobilization ever seen in Mexico as one party after another nominated him as their presidential candidate. First the Authentic Party of the Mexican Revolution (PARM) nominated him. Next followed the Popular Socialist Party (PPS) and the Socialist Party of Workers, who changed its name to the Party of the Cardenist Front for National Renewal (PFCRN). These three nominating parties united into the Democratic National Front (FDN).

Cardenas’ strength as a candidate radiated far beyond the parties nominating him. These three had been loyal satellites of the PRI, supporting the PRI candidates for president (except for the PPS, which in 1952 nominated–or the first and last time-its founder, the old Stalinist Vicente Lombardo Toledano). But wherever Cardenas went, he was met with rallies of tens of thousands. In La Laguna, in Michoacan, in Mexico City Cardenist sympathizers spread like wildfire, especially in the dense belts of misery inhabited by millions of workers and in the campesino areas.

The strength of the FDN upset the political balance. It was a devastating blow to the PRI. But PAN, too, was stripped of its privileged position as the official opposition party-the bi-party hold of the PRI-PAN unraveled like so much wishful thinking.

The electoral balance tipped toward the left or, more precisely, toward the left-center. If in the beginning the Democratic Current seemed to have no chance to reform the PRI, its attractive features were clear to both the official opposition and the independent left Satellite parties such as the PARM and PFCRN immediately offered Cardenas their electoral platform–as could be expected-but the impact was not confined to this official opposition. The left was also drawn into the Cardenas campaign. [to be continued in ATC 17]

*Mexican Bonapartism as used here is a Marxist understanding of the Mexican state under the PRI, whose rule originated in a semi-bureaucratic consolidation of power following the Mexican Revolution of 1910-19. In this state neither capitalists nor workers nor peasants have exercised direct class power; rather, the state has administered a national capitalist economy, incorporating mass organizations of workers and peasants through combinations of reform, populist rhetoric and repression of independent organizations, guaranteeing profits on capitalist investment while forcing the capitalists themselves to accept a dependent political status. The process is described in Adolfo Gilly, The Mexican Revolutio (Verso/NLB, 1983), Dan Labotz, The Crisis of Mexican Labor {Praeger, 1988) and the two-volume work of Manuel Aguilar Mora, El Bonmapartismo Mexicano (Juan Pablos Editor, 1982).

September-October 1988, ATC 16