Against the Current, No. 8, March/April 1987

-

Letter from the Editors

— The Editors -

"Hell on Wheels": A Rank-and-File Chronicle

— Steve Downs - Los Angeles: Stop the Deportations!

-

Israel & the Palestinians: Empire at Close Range

— Witold Jedlicki -

Information Center Closed as Repression Escalates in Israel

— David Finkel - A Petition for Mordecai Vanunu

-

Random Shots: Ollie North, Amerika's Hero?

— R.F. Kampfer - Contrascam

-

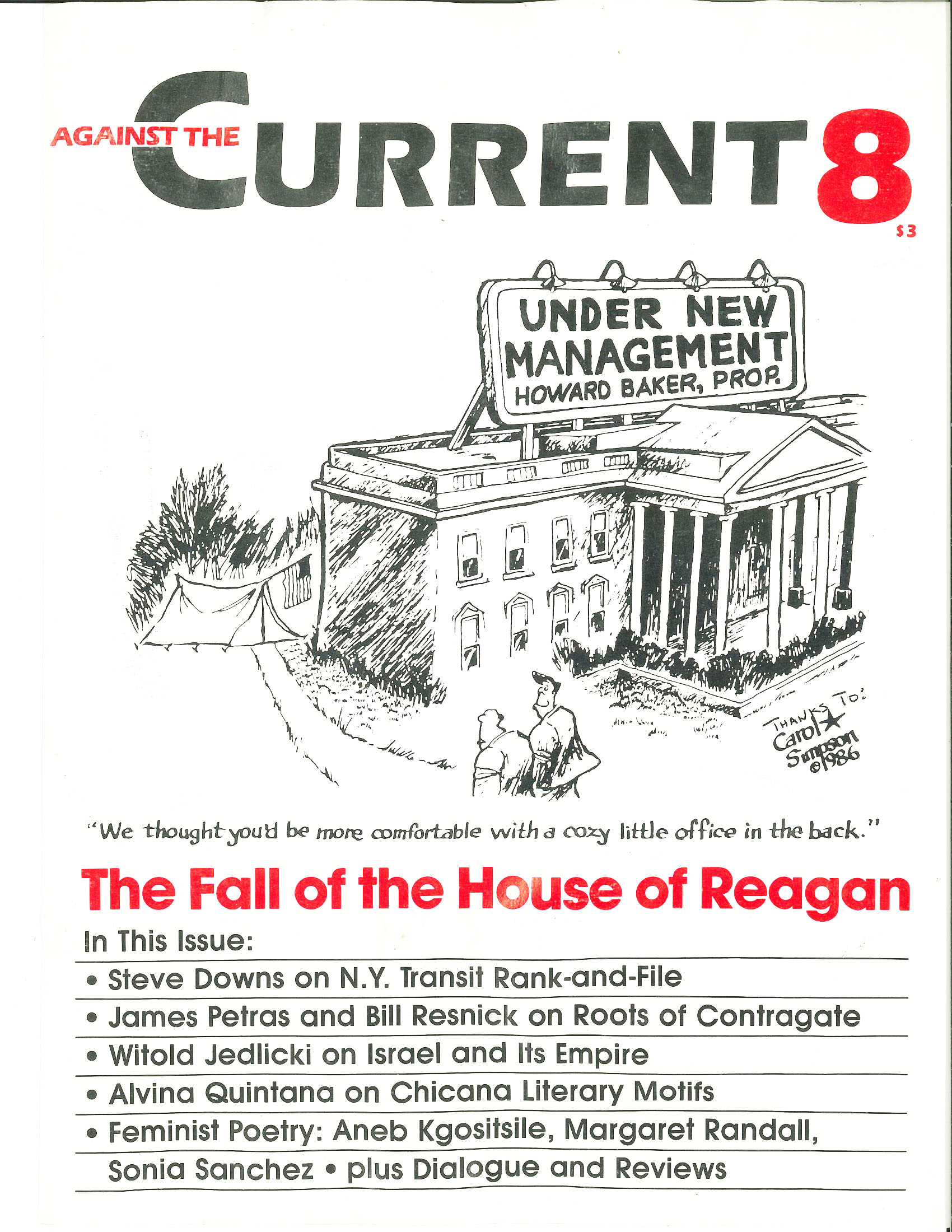

The Fall of the House of Reagan

— Bill Resnick -

Speculators, Lumpen-Intellectuals, & the End of U.S. Hegemony

— James Petras -

Marxism and Utopian Vision

— Michael Löwy -

Chicana Literary Motifs

— Alvina E. Quintana - Feminist Poets Speak Out

-

Philadelphia, Spring 1985

— Sonia Sanchez; graphic by Allison Burkee -

Osage Avenue, Philadelphia, May 13, 1985

— Aneb Kgositsile; graphic by Allison Burkee -

Remaining Options

— Margaret Randall - Dialogue

-

Response to Alex Callinicos: Preparing for the Upturn

— David Finkel -

The Need for Post-Leninism

— Tim Wohlforth -

Comment on Leninism

— Wayne Price -

Another Comment on Leninism

— C.J. Arthur - Reviews

-

The Production of Desire

— David N. Smith -

The Origins of Women's Oppression

— Karen Brodkin Sacks - Letter

-

On Perspectives

— Samuel Farber

Bill Resnick

CONTRAGATE’S GOT everything a soap opera should have. Collapse of the Reagan dynasty. Scandal, disgrace, amnesia. Shady foreigners with terrific names — Manucher Ghorbanifar and the Sultan of Brunei. Comic relief-bringing cakes and an autographed Bible to the Ayatollah. Mystery — Where did all the money go? And finally of course, star crossed lovers — Ollie North’s secretary, one Fawn Hall, also a terrific name, involved as they say, with Arturo Cruz, Jr., son of Arturo the big contra.

The system, says the Tower Commission, was fine; just the people were flawed. That’s another premise of soap opera. Yet something systematic and important is going on. At its core Contragate is one piece of a struggle between two competing U.S. elites-in one corner the upstart right, the Reaganites; in the other the pragmatic establishment made up of traditional conservatives, “moderates,” and liberals.

Their fight is about something very dear to their hearts — how can the U.S. manage and control not just the rest of the world but the U.S. too. Contragate marks the end of one round, with the Reaganites on the ropes, but the fight will continue.

Reagan’s Collapse

New right fortunes waxed and waned through Reagan’s first six years. Their social agenda never got going. Their economic policies were pretty much reversed by the end of the deep recession of 1980-82. Reagan himself was quite flexible, able to nearly effortlessly adopt establishment policies when pushed. But throughout the period he protected far right control of the CIA and NSC (National Security Council) and powerful far right outposts in the Pentagon, State Department, and other agencies.

Reagan was in decline long before Contragate. His weakness was apparent months before, when the Congress enacted mild economic sanctions against South Africa over Reagan’s veto. The November 1986 elections finished him off. Reagan crisscrossed the country, campaigned hard in 15 races. His candidates lost 14, a crushing defeat.

The election disaster defrocked the emperor. Reagan lost his magic, the capacity to intimidate a Congress and press sensitive to political power. That opened the way for Contragate. Oliver North had been called to testify before Congress in 1985 on allegations of illegal official aid to the contras. He brazenly lied, and despite abundant evidence of his involvement, the congressional committee backed off.

After the elections and the sensational Iran disclosures, however, it was easy to go after Reagan and much of the remaining far right.

Contragate

Contragate hurts the right, and they’ll need much time to regroup. It puts established politicos (traditional conservatives and right moving liberals) back in control, for the next two years and probably through the 1988 elections.

In the short run the crisis weakens the U.S. position in the world, certainly in Central America. It also reveals some of the struggles in the U.S. over competing strategies for maintaining U.S. power if not hegemony in the world,

Contragate happened within an historical context shaped by two key trends. First, in a decentralizing world, U.S. economic and political power has been declining. Second is the post-Vietnam syndrome; the U.S. public has become increasingly unwilling to bear the military and economic costs of sustaining the empire.

In this situation U.S. elites came into conflict over basic strategies for managing world and domestic politics. All elite factions saw the U.S. challenged by developments at home and abroad, but they had different analyses of the causes and proper responses to the problems.

For the new right the U.S. was threatened by Communist subversion, and even worse by the flab, permissiveness, and lack of character and discipline at the home front. ABC’s mini-spectacle, “Amerika,” exemplified their thinking. The Russians took over only because the assorted pinkos, peaceniks, feminists, save the whalers, the whole motley assemblage, had weakened true Americanism.

The new right answer for both external threat and internal rot was militarization. The U.S. arms and manpower expansion would threaten the Russians and increase capacity to intervene in the Third World. The build-up of rightist militaries around the globe and paramilitary rightist groups both here and abroad would insure domestic order.

More ambitious, Reaganite militarism aimed not just to control the home front but to reshape it. This meant the considerable expansion of state organs of repression and control, and simultaneous cutback of all forces that support heterodox thought or movements.

Thus we have seen the expansion and tremendous retraining and re-equipping of the National Guards, the CIA and FBI, the special units of the INS, IRS, Justice Department, military police, all the institutions of law and order-to create a “national security state.”

This apparatus was put in firmer control of basic scientific and applied research, and celebrated in popular culture and media. And as the repressive apparatus has been strengthened, the institutions that support critical thought (liberal arts programs of colleges, the Freedom of lnformation Act, etc.) and the institutions that facilitate struggle by subordinate groups (anti-discrimination laws, labor union power) have been attacked and cut back.

The Reaganites were upstarts. The takeover of first the Republican Party and then the national government generated much resentment among Republican moderates and many old hand conservatives in Congress and the Washington establishment.

Some of the old establishment ate their pride and joined, like George Bush; the Texan turned Yale-man then born again right winger became a comic combination. Others just cooperated, intimidated but not won over, biding their time.

When Reaganism began creating as many problems as solutions and then with Reagan’s electoral defeat, the establishment reconstituted around a sort of pragmatic conservatism.

Pragmatist Backlash

The pragmatists include a majority of Congress, led by Daniel Moynihan, a neoliberal Democratic Senator, and Republican Richard Lugar, former head of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee who broke with Reagan on South Africa and became increasingly independent.

Most of the State Department is pragmatist, as are substantial sectors of the CIA and military, much of the academic and think tank national security establishment, and good portions of international business and finance who need a stable world for their transactions.

The factions making up this reconstituted conservative establishment had and still have differences with the new right analysis and vision. New right social policies were seen as dangerously divisive. Voodoo economics was abandoned early. All establishment factions supported the Reagan military build-up, which in fact they had themselves initiated under Jimmy Carter. And they are ready to see its application around the globe. But for pragmatists, military power is not so central, it’s more backdrop for shaping the world through the judicious application of the vast economic, political, cultural, and diplomatic power of the U.S. and its allies.

While the pragmatists will support rightist military states that look like they can maintain control, in general pragmatists see Third World military regimes as potentially unstable, easy targets of rebellion.

Indeed the early Reagan policy of supporting friendly authoritarian regimes dissipated when the realities of Argentina, Haiti, and the Philippines obviously required pragmatist maneuvers, even including human rights rhetoric, which the new right had so despised under Carter.

Thus fairly early on in the Reagan Administration a broad consensus developed on which direction to push Third World states-towards the kinds of government developing in Brazil and Argentina, and perhaps at an early stage in the Philippines, a cosmetic and surface democracy, with mildly competing capitalist elites, where real power resides securely in an expanded oligarchy and military that looks to and operates like its big brothers in the U. S. and Europe.

Still, even with much convergence, a good deal separated the pragmatist establishment and the new right. In particular, the pragmatists opposed what they saw as new right excesses: the wild cowboy ventures presided over by questionable characters, the creation of a right wing international, the uncontrolled extravagance of military spending, and the right-wing notion that the Russians could be bankrupted by an intensified arms race.

Contradictions Accumulate

How did the struggle between the Reaganites and the pragmatic establishment eventuate in Contragate? Reagan’s militarism proved very expensive. All establishment factions became afraid that Reagan would bankrupt the U.S.; and bankrupt countries can’t rule the world.

Moynihan sounded the alarm. Unless Reaganism is abandoned, “We will soon learn that the world’s largest debtor nation does not decide world policy, and that a deindustrialized America can no longer be the arsenal of democracy, much less the terror of the terrorists.”

Of course the U.S. government is not interested in authentic democracy and does more than most to support terrorists: El Salvador’s army, the Nicaraguan contras, Chilean and Indonesian generals, and many more. But Moynihan’s basic point is right and reflects pragmatist thinking: that Reagan was taking too much from schools, transportation, health, economic growth-the real things that maintain the strength of the U.S. and thus the empire.

But not only the pragmatists were skeptical. The voters, still infected by post-Vietnam syndrome, also had to be sold on militarism. When the “evil empire” Russian threat proved counterproductive (remember the European peace movement and the freeze campaign here?), the Reaganites learned from the Israelis: use the dread threat of international terrorism. Iran and the Ayatollah, Libya and Khaddafi, Nicaraguans advancing through Mexico.

Except for Nicaragua, this line worked pretty well in generating support for the military build-up. But it had a downside: after six years of portraying Iran as pure terror, Reagan couldn’t very well send cake and missiles.

Reagan wanted to do what every modern President has done-make alliances with dictators who can be paid to do our dirty work. To be sure, paying off freelance kidnappers, the little groups, is generally self-defeating; they multiply. But bribing a state is different; the state can not only discipline its own armed men, but can also police the whole area.

The U.S. hope was that a cooperative Iran would help control Lebanon, balance the Syria/USSR alliance, and come to tolerate Saudi Arabia and the emirates. However rational this plan, having hate mongered about Iran, and having so often promised never to deal with terrorists, Reagan couldn’t go public.

Once discovered, the secret shenanigans seemed another betrayal, more official lying, this time by Mr. Integrity himself. It was just the stuff to rouse the press and create a scandal/sensation.

The Nicaragua part of Contragate can also be traced to resistance to Reaganism. Part of the militarization was expansion of the CIA, more covert action, and creation of paramilitary thug groups around the globe. The symbol and major public thrust of this entire initiative was the creation of the contras to attack Nicaragua.

Now the pragmatists are not opposed to thuggery and assassination. But discreetly and in moderation! Reagan’s adventurous ness and affection for the craziest right wingers seemed to them very dangerous. The right-wing international that Reagan was creating threatened stability in many countries. Reagan’s loose talk and actions like the Libyan bombing frightened European and other allies. It reduced confidence in U.S. leadership. It imperiled the international cooperation that pragmatists seek.

In Latin America militant Reaganism was increasing anti-Yankee feelings. That could threaten orderly repayment of the debt, and also destabilize the bourgeois governments so painfully and slowly being constructed.

Furthermore, establishment elites did not see the situation as terribly desperate, requiring heroic military action. Reaganite hysteria had little foundation.

If the U.S. was no longer controlling the world, Russia and Eastern Europe were in even worse shape. Yes, international capitalism has fallen into permanent crisis. Many huge problems threaten stability. But there are no real military or political challenges to U.S. power, and never has the left, in any variety, individually or all combined, been weaker To be sure, the problems of the U.S. and world economy are severe. The establishment strategy-some sort of coordinated effort by the U.S., Europe, and Japan-is more a dream than a blueprint, and perhaps impossible in view of their conflicts.

But the problems of the world and U.S. economies would certainly not be solved by hyper-militarization, which in fact would be destabilizing. An arms build-up was useful; cuts in welfare state programs to finance it seemed prudent; the rooting out of some established liberal interests was fine; but Reaganite adventurism had to be resisted.

The Reagan project had a serious setback in 1984, with the mining of Nicaragua’s harbors. Clumsy, internationally embarrassing, it generated sympathy for Nicaragua. The pragmatists gained enough strength in Congress to pass the Boland Amendment.

Direct U.S. military aid to the contras became illegal. The Reaganites persisted in their holy war in secret, and its execution was as poor as the mining of Corinto’s harbor. Ultimately it blew up in their faces.

So in summary, Contragate occurred because the right could not gain popular or retain elite support for the policy of hypermilitarization.

In the case of Iran the Reagan project was derailed because to win support for hypermilitarization the administration had to promote the spectre of terrorism, including Iran’s. The effort to carry out a traditional policy-an alliance with an authoritarian state-then led to political disaster.

In the case of Nicaragua, resistance to creation of a right-wing international and destabilizing covert activities led to the Boland Amendment, and then to secret and illegal conduct of the holy war.

Contragate and the Big Picture

It’s tempting to see Contragate as the failure of a desperate ruling class strategy to regain world hegemony, or further evidence of a decline in U.S. power, as another sign of the “End of the American Century,” as indication of the bankruptcy of the U.S. elite, or some such global pattern.

This sort of apocalyptic or grand analysis downplays the peculiar currents of U.S. politics and the resilience of capitalist power. Obviously Contragate occurred in a political context set by economic decline, dislocation, and threat, but its specific features and overall meaning have to be understood as the result of maneuvers by powerful elite factions whose resources are still very great.

Contragate was the end of a rightist putsch, which had already lost much of its steam. The putsch itself occurred in the context of liberalism’s collapse attendant on severe dislocations in the U.S. economy (inflation and unemployment as the symptoms) and a perceived decline of U.S. international strength.

The rightist program was as much a project for the political reconstruction of the U.S. (militarization of the home front), as it was a rational, calculated attempt to regain world power or safeguard the empire.

The entire U.S. elite felt the need to project more power in the world, and they welcomed the Reagan tax cuts and “deregulation.” But Reaganite policy, for instance the early monetarism, the arms build-up, Star Wars, represented primarily parochial interests (the rightists themselves, the military and arms industries, the banks) and not any generalized establishment consensus.

Reaganism was not simply a direct response to economic and geopolitical imperatives. It was also a contingent and conjunctural creature of U.S. politics: a counter-elite had exploited popular discontent to gain power, and sought to reshape politics to further its program. It fell when the multiple costs of its policies eroded popular support and permitted fightback by establishment elites.

Beyond Contragate: Tomorrow’s Politics

The rightists are out; a conservative establishment is back in charge. They’re in control of the Congress. There’s been a dean sweep in the White House, when Pat Buchanan and Donald Regan left; William Casey has handed over the CIA to William Webster; Howard Baker, an old congressional leader, an establishment conservative, is now chief of staff in the White House.

Ed Meese still heads the Department of Justice and Caspar Weinberger the Pentagon, but their room to maneuver is limited. The last Reaganite is the Gipper himself, and he’ll be hard put to read his lines. So what does it mean?

In foreign policy there may be new directions. Arms control is again a possibility. The new Reagan team desperately needs a success; the Russians desperately want an arms control agreement.

As to Nicaragua, whether or not contra aid continues, pragmatists have no interest in permitting a revolution to succeed, Even if the contras collapse, economic, diplomatic, and political pressure will continue.

U.S. foreign policy will have a new tone. For Reagan even South African whites were good guys whose reform impulses were frustrated by intransigent Blacks. Pragmatist Washington will firmly denounce apartheid, push for minor concessions, all the while doing everything possible to bolster minority rule.

In the Philippines Mrs. Aquino will get more support; the U.S. may even promote land reform, but of a cosmetic variety that enhances the rule of the plantation owners and cash crop exporters.

As to the Middle East, there is neither time, people, nor energy to engage Israel’s rightist frenzy or its Washington lobby. After a brief respite, overtures to Iran will continue.

The key is reviving the international economy-that would take all the pressure off. The pragmatist conservatives now in power will seek to coordinate the vast power of Europe, Japan, and the U.S. to shape the world.

They’ll cut some military spending in favor of productive investment, but in the absence of a vast increase in world demand, investment is unattractive. They’ll try to get the big banks to ease up some on the Third World. They’ll try to improve the terms of international trade to benefit U.S. manufacturers.

Mostly they’ll try to mend fences within world capitalism, to build an integrated effort to revive their economies and to force the Third World to toe the line. Cooperation will however be difficult to obtain. Problems of the world economy have no obvious solution.

Domestic Politics Governance requires popular confidence in the state and its institutions, a sense of legitimacy of the ruling elite. Reagan gave this a boost. That’s now ended and popular alienation is even greater. In the short run Reagan’s collapse crushes the right and weakens Republicans generally. He was their champion and standard bearer. Reaganism has gone down like Nixon and LBJ-in weakness, deceit, infighting-and voters seem to punish this in the next election.

In the long run however the rabid right didn’t lose much that they weren’t destined to lose fairly soon anyway, i.e. Reagan’s patronage. They didn’t get booted out in the usual way, from which it’s hard to recover-discredited in economic disaster. In the absence of a strong contending left, anger at the “politicians” only helps the outsiders of the right.

After six years of Reaganism the moderate conservatives are back on top, with everything just a bit worse and no answers in sight. The monetarism of Reaganism’s first two years was a disaster. The military Keynesianism of the last four added mountains of debt but did not restore the economy.

Perhaps they can muddle through. But deep crisis is very possible. Without growth of a movement with a credible program for reconstruction, U.S. politics will alternate between increasingly furious right wingers and an increasingly conservative establishment.

March-April 1987, ATC 8