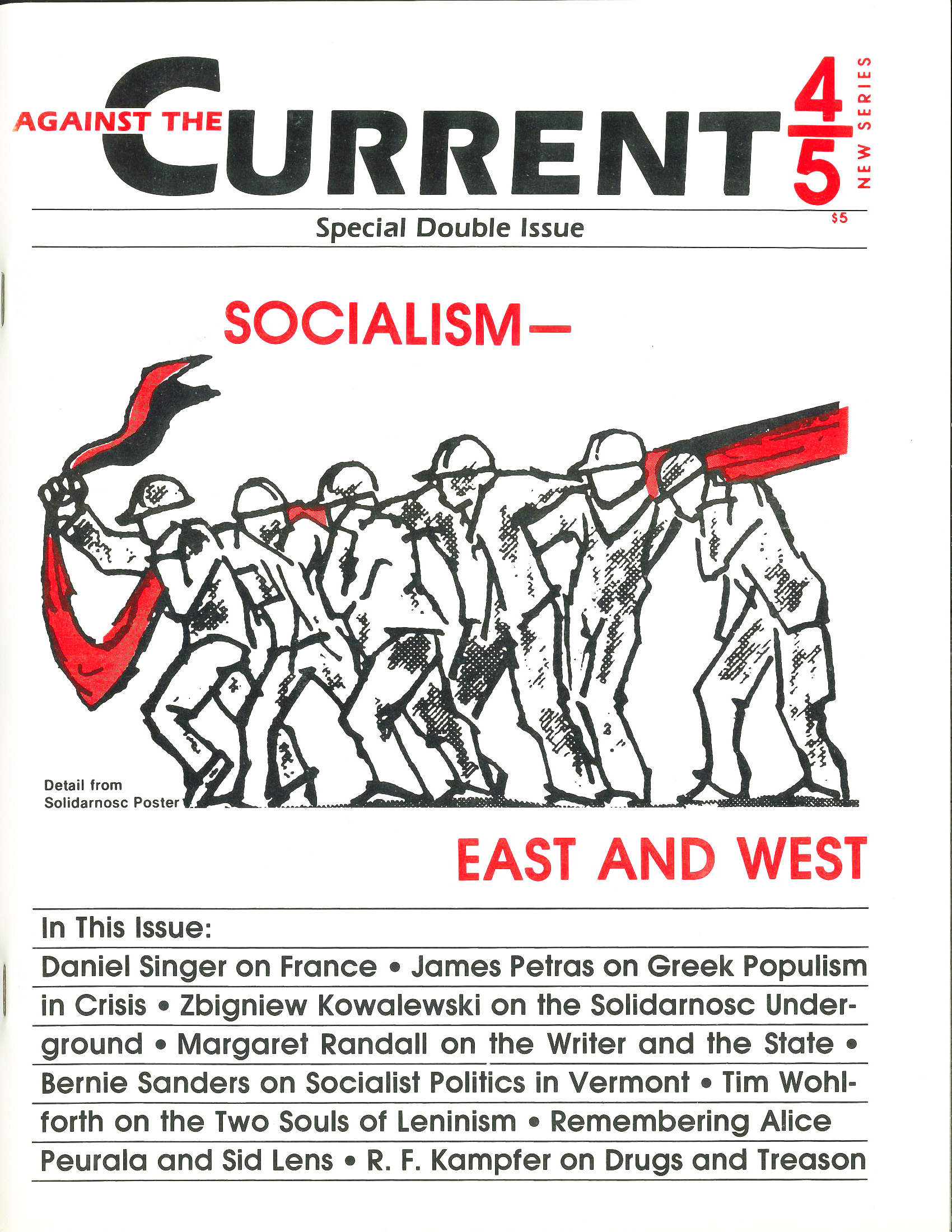

Against the Current No. 4-5, September-December 1986

-

The Elecions and the Left

— Robert Brenner, Warren Montag & Charlie Post -

Bernie Sanders' Campaign: A Step Forward

— Dianne Feeley & David Finkel -

Socialist Campaign in Vermont

— Bernie Sanders -

Stop the LaRouche PANIC!

— Peter Drucker -

Random Shots: Confederate $ for the Contras

— R.F. Kampfer -

Letter

— Donald Kenner - Worldwide Freedom Struggle

-

The State's Imagination -- and Mine

— Margaret Randall -

Poems

— Margaret Randall -

The French Left at a Tragic Impasse

— an interview with Daniel Singer -

Greece: The Crisis of a Crumbling Populism

— James Petras -

Solidarnosc Today: View from the Left

— Zbigniew M. Kowalewski -

Review: Poland Under Black Light

— Ewa Wiosna -

Review: Give Us Back Our Factories!

— Barbara Zeluck -

The Two Souls of Leninism

— Tim Wohlforth -

Guatemala: A New Movement Rises from the Ashes of Genocide

— Jane Slaughter -

Immigration: Whose Dilemma?

— Hector Ramos -

Chile -- New Struggles, New Hopes

— Eric Chester - Reviews

-

Detroit Labor's Rich Legacy

— Marty Glaberman -

Patterns of Rank-and-File Power

— Nelson Lichtenstein -

An Anthology of Radical America

— Kent Worchester -

Israel: Lifeline for Apartheid

— Mark Dressler - In Memoriam

-

Alice Peurala, Unionist and Socialist

— Dot Peters -

Sid Lens, 1912-1986

— Patrick Quinn

an interview with Daniel Singer

THIS INTERVIEW BEGINS with Daniel Singer’s opening remarks at a talk he gave at the New York Marist School in 1986. The interviewers were Robert Brenner and Samuel Farber.

REVOLUTIONS, ROSA LUXEMBURG wrote somewhere, are the only kind of war in which, really, ultimate victory can only be achieved through a series of defeats. The implication is that defeats need not necessarily be in vain, provided that we learn something from them. And though ultimately victory looms very, very distant on the European horizon at the present moment, it is possible to draw some lessons from the severe defeats suffered by the French Left in the recent election.

But was it a severe blow? Judging by the early rejoicing by the French socialists who were dizzy with the 32 % they won, you may doubt whether it was a defeat. And it is true that, in a sense, the French Socialists have tiptoed off the governmental stage without drama or, if I can borrow the by now clichéd words of T.S. Eliot, not with a bang but with a whimper.

But if there was a relative restraint of the respectable right on that election night of March 16, this is no consolation for us at all, because the relative smallness of their victory was not due in any way to the sudden recovery of the Left. It was due to the victory of the National Front, the new fascists. The only people who really had reason to celebrate that night were the new fascists, because they won something like 10 % of the votes cast in the general election and 35 deputies. For Le Pen and the National Front, that 10% figure was a triumph.

In contrast, for the Communist Party, who received just about the same 10% of the vote, the election marked another step on their road to political irrelevance.

But, if we just leave aside for the moment the shifts within each camp, and if we look at the balance of electoral power between the sides, between the Left and the Right, then the swing was tremendous. In 1981, the Left won the general election, receiving something like 56 % of the vote to 43% of the vote for the right. However, in March 1986, it was exactly the reverse: the Right had 55 % of the vote, and the Left had only 44%.

And it was not only an electoral swing. The defeat of the Left goes much deeper than that. The labor movement is on the defensive and in total disarray. The intellectual rule of the Right looks absolute: at the moment, the cultural climate in France has changed beyond recognition. People who left Paris fifteen years and came back now just wouldn’t believe their eyes and their ears. They would have left a country or capital where imagination was supposed to be groping for power, and they would have returned to a country which, forgive me, is as backward politically as the United States.

Now what do the Socialists have to say about all this? What do they claim? They say, “We’ve managed well, and having managed well, we’ll come back and we’ll come back soon.” And that seems to me quite a reasonable proposition in a way. After all, ever since, say Ebert and Scheidemann, the German Social Democratic leaders who officiated when Rosa Luxemburg and Carl Leibknecht were being massacred, and going through to Harold Wilson, James Callahan, and Helmut Schmidt–or passing through a Frenchman like Guy Mollet who was well-known as the man of the Algerian War–such socialists were always welcomed by big business to run its own affairs … or, as the last French Socialist Prime Minister Laurent Fabius said in a Freudian slip-of-the tongue, “We do their dirty work.”

What the French now present as the “alternance,” that is to say a form of consensus politics-the fact that you switch from the Tories to Labor and back, from Christian Democrats to Social Democrats, from Republicans to Democrats-that’s something that has been the rule in Britain, in Germany, in the United States for years. But the great difference between France and Britain was that in Britain people did not at all have the impression that you could change life fundamentally by radical political action, whereas in France people did retain that idea. That was the great difference, and it is the great achievement of Francois Mitterrand to have eliminated it.

Robert Brenner & Samuel Farber for ATC: You’ve written that, during its initial period in office, Mitterrand’s Socialist government passed certain reforms. It tried to implement a Keynesian expansionary policy to achieve growth and cut unemployment, and it nationalized certain key industrial sectors. But as the French economy came under increasing pressure, due to rising inflation, growing deficits in both trade and payment balances, and the flight of capital, Mitterrand’s government assumed methods and goals that made it virtually indistinguishable from other capitalist governments. Basically, it sought to make the capitalist economy function better through seeking to restore profits at the expense of the working class. Did Mitterrand’s government have any alternatives to what it did? Some, who might be called “socialist realists,” are saying that Mitterrand did all that can be expected of any socialist government, given the state of the world capitalist economy. Would you agree? What should a genuinely socialist party have done?

DS: I’d like to subdivide the question. First, did the Mitterrand government have any alternative being what it was and is, that is being a social democratic government? To that you could answer, it probably didn’t. We’re in a new historical period in economic terms. The thirty years of unprecedented growth, which conditioned rising wages, the expansion of the welfare state, etc. is over, and the capitalists will no longer allow the workers improved living standards without a big fight.

But in that case the admission by what you call the “socialist realists” that, in this new situation, they haven’t got an answer, specifically, that in this new economic period there is little scope for reforms, is very interesting indeed. In other words, what they imply is that we’ve reached a stage, where either you’ve got to become more radical, or you’ve got to surrender. That seems to me quite an interesting admission for supporters of a social democratic position to make.

On the other hand, another way of interpreting your question would be, did the Mitterrand government have any alternative, given what had come before? Here you have to take into account that the Socialists’ electoral victory came without having been preceded by any social movement. That’s the fundamental difference between Mitterrand’s election in 1981 and the election of Leon Blum’s Popular Front government in 1936, which took place at the time of huge mass workers’ struggles, the general strike and factory occupations.

To say why there were no social movements in 1981, you have to go back at least to 1968, to the great movement of students and workers of that year. After that great upheaval, it was up to the “respectable left,” the Socialist and Communist Parties, to channel the popular energies into purely parliamentary water. This took a long time, of course, but the upshot was that by the time of Mitterrand’s electoral victory, the dynamism of the movements was entirely spent.

Secondly, reflecting some of the same processes, Mitterrand’s victory came in the wake of a huge ideological defeat: the complete success of the establishment, the ruling class if you will, in recovering completely its ideological hegemony in the period, say, from the mid-1970s to 1980.

Finally, you have an electoral victory without any serious economic debate on the left on the economic issues, concerning the kind of crisis we are going through, and how the left could respond.

So, to sum up, my answer would be that there was no alternative in both of the following senses. There were no viable social democratic solutions to this situation. Second, given what came before-the decline of the movements which went along with the systematic attempts of the Socialist and Communist parties to channel social struggles into the parliamentary road and the restoration of ruling class hegemony-no other alternative could have been expected.

But we still have another question: What should a genuinely socialist party have done? Now, a genuinely socialist party could only have come to office on the basis of dynamic mass movements. That’s first. Even so, I’m not trying to minimize the problems such a government would have faced. But a genuinely socialist government would surely have used nationalization as the basis for the installation of new social relations of work in the factory and the office, and it would have been necessary to invent new forms of democratic planning. A genuinely socialist government would have conducted a debate there was no such debate before or during the Mitterrand government’s tenure-on the merits and disadvantages of protected planned economy and the merits and disadvantages of the participation in the international division of labor.

The point is, of course, you have to confront immediately the problem of the limits imposed upon a socialist experiment by the nation state’s existence within a capitalist world economy. But having the support of an explosive mass movement, you could have used that power to force some concessions from your common market “partners” and rivals.

When, in 1936, the French popular front won an electoral victory and the workers occupied factories, the bourgeoisie’s position was “give them something because otherwise they’re going to take it all away from us.” At that time, you counted, because you had the power. Obviously, had a genuinely socialist government come to France in 1981, there would have been a very strong international reaction, but such a regime would have been able to appeal to workers of other nations over the heads of their governments and attract support by example. I’m not trying to minimize the problems. In any case, the task would have been enormous, but the situation would have been entirely different from what it was in 1981, with entirely different possibilities.

ATC: Some would say, then, that although, in the abstract, a left government could have taken an alternative road, in particular by focusing attention on mobilizing the working class and creating the conditions for such mobilization, we already know from long experience that social democratic parties and social democratic governments will not do this. These parties are based on their parliamentary delegations, their bureaucracies and in some instances the trade union officialdom and they confine themselves strictly to electoralism. Did the Left have any reason to expect Mitterrand to do anything different from what he did, and does the Left have any reason to expect any such party in the West to do anything different from what Mitterrand did?

DS: But I think it was not just the Left but people in general who expected something else, even if they had no reason for such an expectation, and that is something that we have to take into account; it is a factor and you cannot ignore it. On the other hand, what’s going to happen will also depend very much on the capacity of the movement from below to force the government, to push them to do certain things. If there had been a bit more pressure from below, things might have gone somewhat differently. I doubt that even Mitterrand and his government wanted to do exactly what they ended up doing.

Perhaps the main lesson, though, is, as I said earlier, that the Mitterrand experience shows to what extent the social democratic parties are now even more limited than they were. If the Mitterrand government had come to power in the thirty years or so immediately after World War II, they would probably have been able to do more than it did this time.

ATC: In relationship to that lesson, then: some sections of the far left called for the election of Socialists and Communists on the slogan of putting a workers’ government in power. Do you think that was a correct approach? Did you think the Left should support the election of Mitterand’s Socialist Party and, more broadly, the election of labor and social democratic governments?

DS: I doubt if one can have general rules about just what to do in a situation like that. But one dictum you should follow is don’t tell lies. I mean you should tell your supporters or the masses of people what you really believe. This is to say, that it is absurd to use the slogan of putting a workers’ government in power when you know that the government which would come to power would be a government of the Socialist Party and the Communist Party. Such a government simply has nothing to do with a government from below, a government run by workers. We know what they will try to do.

But let me try to explain my saying that you can’t have a general rule. Let us remember that in 1968 during the rising, there was a slogan which one could politely translate “An election is a trap for suckers.” Now that slogan was quite valid at that moment in the development of the movement. It meant that we should now go to try to push toward power or go ahead with building the movement. In that situation to stop for elections would have been silly even in a parliamentary system like that of France, because this was an exceptional situation. But you can’t make that into a general rule, even if you don’t have an electoralist approach, even if you’re not suffering from parliamentary cretinism.

You have to take into account the fact that, in most instances, the masses do consider it of significance whether the Left, broadly speaking, wins an electoral victory or it suffers a defeat. It has a real impact on them, especially their morale, whether or not the Left wins. Therefore you would not be understood, if you just stood by and said, “Left and Right are exactly the same.” For example, when the Communists broke the unity of the Left in 1977, by breaking from the Common Front with the Socialists, they didn’t adequately explain why, and they ended up paying a big penalty by 1981, because people wanted an electoral victory of the Left at least to defeat the Right and didn’t quite understand why the Communist Party didn’t do so. So one has to take into account what is the mood of the people and one has also to tell them the truth.

Secondly, and this is most important, what you do with respect to elections obviously is dependent upon what sort of social movement you can create, or have created. At this point it is extremely important to teach the people, develop their political consciousness as much as possible and here you can use elections in a variety of ways.

For example, in France, some far left groups are using elections for propaganda. For, in an election period, you get opportunities to be listened to that usually aren’t available. In France, you can get on television and on radio and get across certain things that otherwise would not be heard. It’s important to take advantage of this moment when people are listening precisely to make antielectoralist propaganda. This is an excellent time to get across the point that not everything happens in Parliament, and that everything depends on your own fight, on your own struggles, and so on. I guess, then, that while there are no general rules as to what to do, there are certain general principles of proper socialist activity.

ATC: Your focus so far has been on the development of militant mass movements as the key to, or focus for, any sort of effective left work, whether this be running in elections, pressuring a social democratic government, or merely using elections to carry on propaganda. But you also said that since ’68, the mass movements have experienced a long term process of decline. Could you talk about this historical evolution?

DS: To begin with, 1968 was a situation in which for the first time for a very long time in Western Europe you had a true political upheaval. There was no socialist revolution, or anything of that kind; I don’t want to create a false image. But, there was the biggest general strike that we’ve had in France, and it was shaking the system. There was, moreover, an ambiguous, but very interesting link between students and workers. So after that the establishment faced a really serious task in attempting to restore political stability.

One thing which was critical here was a strange alliance, if you will, between the bourgeois establishment and the allegedly left-wing parties, including especially the Communist Party. So, from just after the explosion, the Communists were saying that we now know that we can’t change life by revolutionary struggle, but we can change course by electoral methods. The parody of this came at one stage when the youth of the Communist Party adopted the slogan of the far left in May ’68, “The only solution is revolution,” by adding to it the phrase, “and the only means to it is the Common Program,” i.e. the electoral alliance between the Communist Party and the Socialist Party.

The point is that just before May ’68, all of the respectable left-wing parties had their eyes completely on the parliamentary horizon … and it actually looked like an electoral victory might be possible. But that was swept aside by May ’68, so you had to try to put it all back together again. This meant that it was critical, at that point, when the Communist Party was actually much stronger than the Socialist Party, for the Communists to promote the Socialists, to present them as partners, and to restore the idea that the Left could win an electoral victory. For this, you had the Common Program, and the CP-SP electoral bloc behind it. But this was no easy task to accomplish, for there was a real ferment and much activity occurring at the time.

The thing is, the movement did not end, by any means, in ’68. Within a few years, entirely new movements, like women’s liberation and the ecology movement, were added onto the workers and student movements of ’68. On top of that, very soon, you had the beginning of the economic crisis. If there had been a way to bring the movements together, and to take into account and take advantage of the emerging economic crisis-if a common project could have been created, fusing all aspects of the situation–things would have been very dangerous for the system. I’m not saying that ’68 was already a revolutionary situation, but you could have gone into a sort of pre-revolutionary situation.

What was important for the bourgeois establishment in order to regain mastery of the situation was to convince people that there was no alternative to the present system. Here ideology played its part. I must say what impressed me was the ability of the system to regain stability without massive repression. Now, to accomplish this function, you couldn’t have old fuddy duddies, pillars of the establishment, coming in to warn the youth against the radical threat. What you needed were turncoats-ex-’68ers, ex-Maoists, ex-radicals, who suddenly saw the light-who could be brought in to explain the dangers, how radical revolution would lead to con centration camps.

So, you had the whole campaign around Solzhenitsyn. I’m not saying that one shouldn’t talk about Russian concentration camps, far from it. But you suddenly had these Christopher Columbuses who made the discovery of the Russian concentration camps in 1975, and who were using this to say that while it was fine to rebel individually, if you wanted to revolt collectively with a total project for revolutionizing the whole society, this would lead to the gulag. On the one hand there was Solzhenitsyn saying this, and he is a man of direct experience. On the other hand you had the young radicals following him.

It is true that this was on a very low level intellectually, a repetition in France of something that had already happened much earlier in other western countries, like the “God that Failed” group of ex-CPers in the late 40s and early S0s. In any case, it had been prevented from happening previously in France largely because of the strength of the CP and the general intellectual climate, but when it did happen in the middle to late 70s, it had a devastating impact on ideology and the French political scene.

The result was that by the time Mitterrand came to office, the cultural and political climate had completely changed. Thus, when people began thinking that maybe capitalism is no good, because of the onset of the capitalist economic crisis and the shattering of the myth of permanent growth, they also tended to feel that your only alternatives were to make small changes within the system or to opt for a radical alternative which would inevitably lead to concentration camps.

In a sense this brings us to a general point that I haven’t really mentioned up to now, but which needs to be emphasized. This is the impact of the discrediting of the Soviet model, or we would say the Stalinist model, which really began in earnest thirty years ago with Krushchev’s speech. Many of us have always emphasized that without discrediting that model-the idea that the soviet system was a model for socialism or could provide any sort of acceptable alternative-you would not have a resurrection of the socialist movement, and I think we were perfectly right in saying that. But what the capitalist establishment has largely succeeded in doing is turning that healthy and indispensable proposition into quite a different one-i.e. that there is no radical alternative at all, and that there can be none.

ATC: All this is ironic because, of course, this was the period in which the capitalist economic crisis was first being felt, reducing the viability of reformism and shattering the myth that capitalism could permanently deliver the goods. Could you describe a bit of the nature of a working-class movement in this period at the level of the shops, and what happened to it?

DS: I think it was more than an irony. In fact, quite a lot of the things that happened, and especially the political disarray of the French Left, may be explained in terms of the onset of the economic crisis, and in terms of the failure of the French left properly to examine and debate the economic changes which were occurring. When the historians come to describe the period of the great boom of the thirty years after World War II, they will see it as sort of an exceptional period for continental Europe-unprecedentedly rapid growth, very deep social change, really rapid improvement in standards of living, and the expansion of the welfare state.

Reformism doesn’t develop just because you have wicked leaders; it requires certain objective conditions for its development as well. So, you had, on the one side, the collapse of the Soviet model, and on the other side, the success story of the capitalist economy. This led to the conversion of the whole of the respectable left, the Communists and the Socialists, to participation and to the idea that their job was to manage capitalism better and reform it in favor of the workers, but basically leave it fundamentally unchanged.

But with the onset of the crisis, you got the collapse of the premise on which it all rested, i.e. that the capitalist system would deliver the goods. In the new conditions, it was clear the capitalists, to restore their equilibrium, would never endorse an historical compromise with the working class and its organizations. Quite the contrary. Since the respectable left and all of its organizations had premised their entire politics on permanent growth and permanent cooperation, the economic downturn resulted in bewilderment, not only total bewilderment of the leadership, but bewilderment of the whole labor movement. This was because it had consigned itself entirely to improvement from above done by electoral victory.

Meanwhile, to make things more difficult, even before the Socialists and Communists had come into office, you had changes in the social structure of France resulting from the economic crisis which had a particularly powerful effect on the labor movement. The point is that international competition was undermining the economic viability of those industrial sectors which had previously been the most powerful bastions of labor and the left, such fields as coal mining, ship building, the steel industry, engineering-the big plants in general.

Not only was there no great debate on the economic situation, there was also no debate on the nature of the changes in the composition of the working class which had taken place over the whole postwar period, and especially since the start of the crisis. The social movement was therefore badly undermined by its lack of general perspective, and this was particularly revealed in the difficulties in initiating the absolutely necessary defensive struggles to defend jobs.

Before the 1981 election there was a defensive movement which was quite strong in such areas as the Lorraine steel industry. But the problem was that this movement was entirely dependent on the assumption that once the left-wing government came into office then the situation would change basically and radically. That is to say the solution was going to be electoral. People were fighting strong defensive struggles, with the idea that once the left came into office, it would further nationalization and stimulate the economy to provide jobs for everybody.

ATC: Presumably the Left parties were making this same point?

DS: Exactly. That was the line of the Left parties and of the unions. What you had after that, during the first year after the Socialists won the election, was a certain improvement for the workers, especially some increases in social benefits, even if there was no real change on unemployment. The total package was not as big as described later, but the workers did get something the first year.

But the whole thing was based on the absurd idea that the Socialists could pursue an expansionary policy in France within an international capitalist market in which, everywhere else, governments were pursuing contractionary policies and deflation. It was quite clear that very rapidly you were going to run into difficulty. It took roughly six months, I think, for the government to realize that its whole strategy didn’t have a leg to stand on. It was a situation where you either had to radicalize or surrender.

Of course, nothing had been prepared to make it possible to radicalize, nothing had been done to make it possible to govern in this situation, to face the gnomes of Zurich and to prepare the working people for what was going to happen. So what you had was a second year, in which the Socialist government still pretended that it was not changing its program. But after two years, when they were finally compelled to admit to what they were doing, they took a complete somersault, an ideological somersault, and really reproduced the ideology of their right-wing predecessors.

ATC: Now you’ve filled in the background for the approach to the Socialist-Communist electoral effort and government you sketched earlier, and explained your rejection of any call for electing the left unity government as a “workers’ government.”

DS: Yes. It was idiotic for revolutionaries to say to the people that by electing the left you’re going to have a workers’ government. This is because the left government was not in any way going to be a workers’ government. But, on the other hand, it would not have been correct to put forward the slogan that it makes no difference-left or right, it’s the same thing, they both stink in the same way. With that sort of platform in 1980-1981 no one would have understood you.

ATC: In that case, what should the genuine left have said in the run up to the election in 1981?

DS: It should have said what we need is to revitalize the social movement. The workers need to do things in their factories. Even while we back the electoral victory of the Left against the Right, we will still need to be able to impose on a Socialist-Communist government the policies we need.

ATC: Nevertheless, it seems that most of the far left focused on the slogan “Elect the Left so as to put a Workers’ Government in Power.” Why do you think the leftists to the left of the Socialists and Communists approached the elections in this way?

DS: There is, at the present moment, a deep crisis of the revolutionary left. When I said, a moment ago, that the Socialists and Communists succeeded, over a period of time, in channeling most of the movement which had developed in May ’68 and the period after that back onto the parliamentary track, it was to say also that they succeeded simultaneously in their goal of reducing the scope available for the radicals to their left, what we’re calling the revolutionary left.

If one looks at this moment at the situation of the far left, it is in a very sorry state. The Maoists have vanished; the Trotskyists have shrunk to a very small proportion; the PSU (i.e. the radical socialist party, which was once actually fairly large) is talking of self-dissolution and certainly doesn’t know where to go; the Greens haven’t taken off in France. So if you take it all together-call it bankruptcy or call it inability to face up to the requirements of the situation-the far left was not even sufficiently credible or able to carry out the absolutely indispensable debate on the issues raised by the new economic and political situation.

As I said before, I think the greatest achievement of the capitalist establishment has been to destroy in countries where it once existed the belief in a radical alternative. The important thing is to see again that we can provide that alternative. In at least one respect, this is quite easy: we can show very clearly the inadequacies of the capitalist system, with its mass unemployment, and it is critical to do so.

In a discussion about this maybe fifteen or twenty years ago, people on the right would say to us, “why do you want to change the system, it’s working.” If we had said at that time that you’d have two and a half million unemployed in France, a million unemployed in Germany, three million unemployed in Britain in the 1980s, we would have been taken to be completely crazy. But today you do have mass unemployment in this mad world where you can put a man on the moon and invent extraordinary computers and fantastic robots and so on. Even despite this, it continues to be successfully proclaimed that freedom means the freedom of the market and capitalism is the only real alternative.

Without a certain vision, in fact without certain guarantees-guarantees of democratic institutions, guarantees that there won’t again be a dictatorship over the proletariat-people won’t be willing to move forward.

ATC: So what we’ve had in France is so-called socialist government with a fierce policy of restoring the conditions for capital accumulation on a national basis, with resulting suffering for broad layers of the working class. Has this opened the way for the rise of the Right? How would you assess the importance of the Le Pen [neofascist leader} phenomenon and how would you analyze it?

DS: The Le Pen phenomenon is clearly dangerous. That you can have in a country like France one-tenth of the electorate voting for Le Pen, a fascist, is a very important fact. I don’t think you yet have, as a mass phenomenon, the switch from the Communist Party to Le Pen by working class voters. On the other hand, there is an important new fascist vote now in the popular districts [i.e., working class] in Paris, even in the Red Belt surrounding Paris, although it’s also true that Paris itself is changing in social terms and ceasing to be popular.

Le Pen’s support is probably mostly lower-middle class, but it’s not quite certain if it will continue to be confined to that. It is strongest in areas where you have refugees from North Africa, the European ex-settlers who have come back to southern French cities like Marseilles, Montpellier, and so on. That’s a rather sad lesson for us, because many of us were assuming that, once back in France, these people would be voting in protest against the social and economic conditions. They actually did that until this recent revival of the far right.

Two things in combination seem to have been responsible for the vote for Le Pen: you needed both the economic crisis and a left-wing government in office. Neither Le Pen or the extreme right in general carried any electoral weight until 1981. The economic crisis prepared the rise of the National Front, especially because it made it easy to use such a slogan as ‘Two Million Immigrants = Two Million Unemployed.” Nor have the Socialist and Communist parties developed the necessary anti-racist, anti chauvinist propaganda which would have helped to prepare the labor movement for really fighting against xenophobia and all forms of racism.

After 1981, one of the problems raised was giving electoral right to immigrants. Our immigrant workers have no rights, they are completely disenfranchised, as if they were slaves in ancient Greek society.

So the Socialists had promised at some stage that they would at least give the immigrant workers the right to vote in the local elections. But when a Socialist minister who was visiting Algeria mentioned that as a possibility, there was an immediate outcry from the right-wing press and the Socialists and their government immediately caved in, saying the country isn’t ripe for it. In other words, the job of the Left and the Socialists was always to lag, never to lead.

Then, as soon as the Right began to carry its campaign against the immigrants’ getting the vote, Le Pen and his followers immediately took up an even more extreme position on the issue. They could always outbid the respectable right for support on this issue. The result was that the whole climate changed, and the Left ended up going along.

ATC: How then would you sum up on this issue? Has there been a significant shift of the working class to the right?

DS: Let’s put it quite plainly. As I said, the swing to the right in the elections was actually quite large. There has been a general shift in the consciousness of the working class. This brings me back, in conclusion, to emphasize a point I already made: it’s the apparent resignation of the people, the weakening or temporary destruction of the idea that you can radically change life through political action. It’s this which is most serious, and which the left must try to reverse.

September-December 1986, ATC 4-5