Against the Current No. 4-5, September-December 1986

-

The Elecions and the Left

— Robert Brenner, Warren Montag & Charlie Post -

Bernie Sanders' Campaign: A Step Forward

— Dianne Feeley & David Finkel -

Socialist Campaign in Vermont

— Bernie Sanders -

Stop the LaRouche PANIC!

— Peter Drucker -

Random Shots: Confederate $ for the Contras

— R.F. Kampfer -

Letter

— Donald Kenner - Worldwide Freedom Struggle

-

The State's Imagination -- and Mine

— Margaret Randall -

Poems

— Margaret Randall -

The French Left at a Tragic Impasse

— an interview with Daniel Singer -

Greece: The Crisis of a Crumbling Populism

— James Petras -

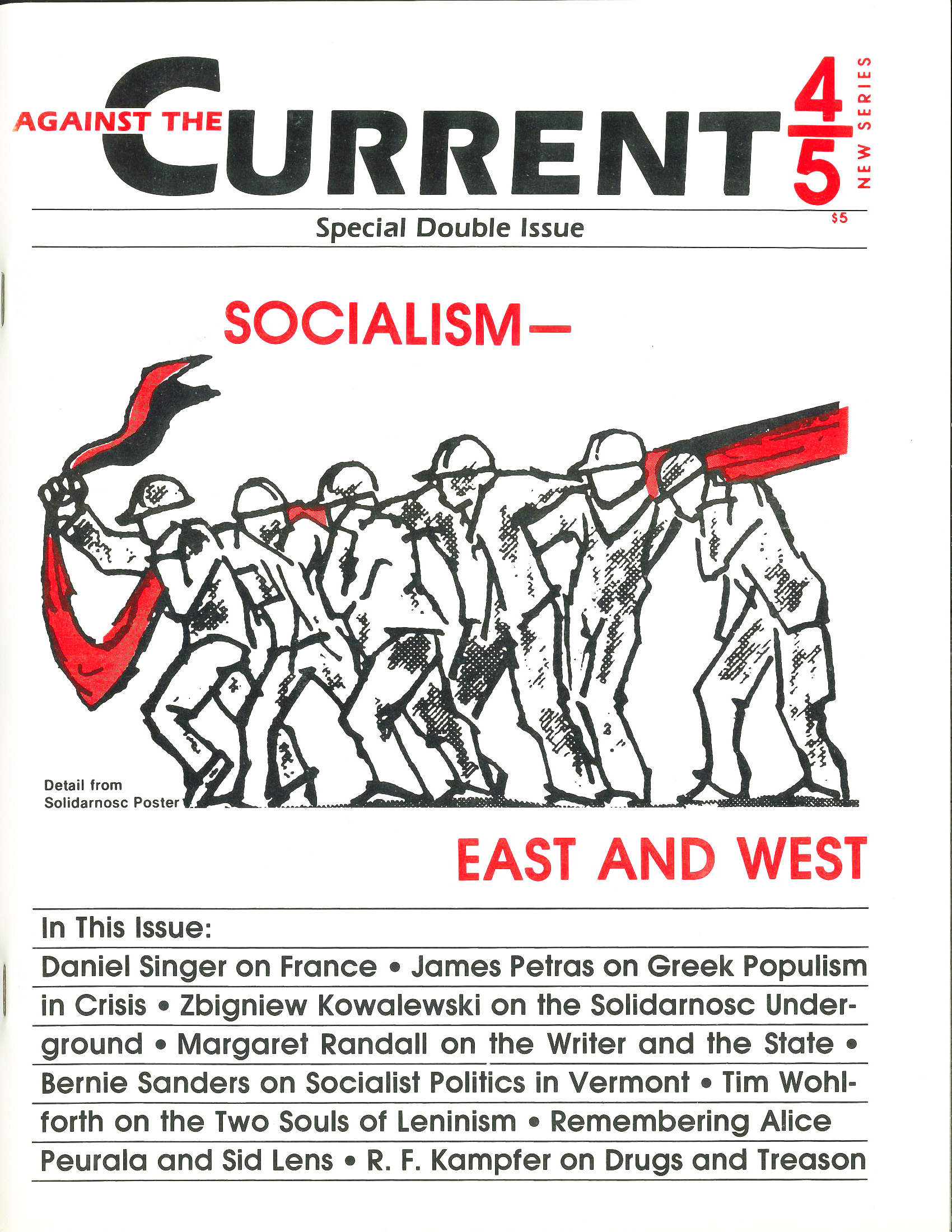

Solidarnosc Today: View from the Left

— Zbigniew M. Kowalewski -

Review: Poland Under Black Light

— Ewa Wiosna -

Review: Give Us Back Our Factories!

— Barbara Zeluck -

The Two Souls of Leninism

— Tim Wohlforth -

Guatemala: A New Movement Rises from the Ashes of Genocide

— Jane Slaughter -

Immigration: Whose Dilemma?

— Hector Ramos -

Chile -- New Struggles, New Hopes

— Eric Chester - Reviews

-

Detroit Labor's Rich Legacy

— Marty Glaberman -

Patterns of Rank-and-File Power

— Nelson Lichtenstein -

An Anthology of Radical America

— Kent Worchester -

Israel: Lifeline for Apartheid

— Mark Dressler - In Memoriam

-

Alice Peurala, Unionist and Socialist

— Dot Peters -

Sid Lens, 1912-1986

— Patrick Quinn

Zbigniew M. Kowalewski

THE DEFEAT of the revolution following the declaration of the state of siege in Poland did not lead to the destruction of the social movement, a first in the Soviet bloc. Solidarnosc, in 1980-81, not only led a revolution of greater mass participation and longer duration than any other in the Eastern bloc, but now, following the December 1981 coup, it has generated a prolonged social resistance.

The Stalinist bureaucracy’s system of rule is totalitarian by its nature; it is based (1) on the holding of the working class as well as the entire civil society in a state of forced atomization; and (2) on the uprooting of all elements of workers’ and citizens’ democracy within society. Although the strong man of the regime, General Jaruzelski, has proclaimed a full “normalization” and has earned the lavish title of “brilliant leader of socialist Poland” from his patrons in the Kremlin, his militarybureaucratic dictatorship is far from reestablishing its base.

The militants of Solidarnosc, fingered by the political police, are objects of a repression that consists not only of being fired from jobs, but also of imprisonment and, at times, even assassination “under mysterious circumstances.” Each time the penal code is reformed, it resembles the classical Stalinist models more closely. The danger of being accused of “betraying the fatherland” or of having ties with the CIA grows.

One of the militants most feared by the bureaucracy, Wladyslaw Frasyniuk, the great workers’ leader of Solidarnosc from Lower Silesia, is suffering systematic repression in jail. Given the impossibility of breaking his indomitable spirit, the repression is aimed at breaking his health and leaving him physically incapacitated. Adam Michnik, who has been a dissident for more than 20 years and has now become the main ideologue of the democratic opposition, finds himself jailed on a nearly permanent basis since December 1981. [Michnik was released in mid-August.]

Nevertheless, in innumerable enterprises, particularly in the larger factories and in some centers of intellectual work such as the research institutes, cells of Solidarnosc militants continue to operate. Other cells are organized as inter-enterprise committees of coordination or as regional leaderships.

There is still a clandestine national leadership. Despite the growing list of its members who have fallen into the hands of the police, the security forces have not been able to break it up, not even with the recent capture of Zbigniew Bujak, who was underground for four and a half years. It is estimated that approximately 10 percent of wage earners continue to pay union dues to Solidarnosc’s enterprise committees.

The legal workers’ councils–the faint residue of the workers’ self-management bodies that arose during the last revolution–are composed, in their great majority, of old militants of Solidarnosc in practically all the enterprises in which workers have been able to force a democratic election. In the big industrial centers, the underground press is distributed in all large and medium-sized enterprises among circles, some of which are larger, some smaller. The monopoly of information, one of the fundamental tools by which the totalitarian bureaucracy rules, has been broken.

The most spectacular expression of the vitality of this resistance is the distribution of more than five hundred–according to some estimates, almost one thousand–independent newspapers, some with impressive circulations, such as Tygodnik Mazowsze (Mazovian Weekly), which has a circulation of several thousand copies each week and is edited by the Warsaw Regional Executive Committee of Solidarnosc.

According to conservative estimates, the underground editors have already published at least 1,200 books. Given the broad interest that they have attracted, [the Paris daily newspaper] Le Monde does not hesitate to dedicate entire pages to some of them, such as Konspira (The Underground), a book of interviews with underground leaders of Solidarnosc, or Oni (Them), a book of interviews with top-ranking Polish Stalinist leaders from the ’40s and ’50s. The network of illegal presses is so vast that the regime has been unable to wipe them out, even though they are a primary target of the police.

A process of differentiation and polarization is inevitable in a social movement. “Politicized” currents or political groups of differing orientations have formed within or around Solidarity. These groups range from (1) the Fighting Solidarnosc Organization, the oldest such group (having already formed by the spring of 1982), which covers its ideological haziness with an elevated level of activism; (2) political groups formed around the journals Wala (Will) and Robotnik (Worker), which vacillate in their frame of reference between social democracy and the “alternative” movements of East and West; to (3) the revolutionary left, which has appeared more recently. The Workers’ Opposition Alliance is presided over from the underground by a 27-year-old Silesian worker, Damian Dziubelski.

However, for primarily objective reasons, there are dark clouds as well as silver linings. The experience of the international workers movement shows that it is very difficult to maintain for years the activity of clandestine political organizations composed of professional militants. To preserve a social movement under such conditions is incomparably more difficult.

Solidarnosc today is composed of a myriad of more or less autonomous groups, loosely interwoven horizontally and vertically, which act to a large extent on their own, according to their own very differing capacities for initiative. The coordinating committees, like the Solidarnosc leaderships at the regional and national levels, do not coordinate or lead very much; rather they function as base.

Workers’ economic struggles–strikes or threats of strikes–occur frequently in enterprises. In the first half of 1985, they forced the regime to grant nominal salary raises of 20 percent instead of the planned 12 percent. But these struggles are carried out in a completely dispersed manner, in a manner very similar to struggles prior to August 1980. This obliges us to adjust the image of effectiveness with which the leaders of Solidarnosc are currently credited.

Not the slightest bit of the 30 percent lowering of real wages which accompanied the declaration of the state of siege has been recovered up until now. According to the estimates published by the network of Solidarnosc commissions in the key enterprises, the cost of living for families of industrial workers with incomes not exceeding the national average per capita increased from 6,000 zlotys at the end of 1984 to 8,700 zlotys by the end of 1985. In the same period, the prices of basic articles selected for the Network’s poll increased by 37 percent.

An extremely worrisome increase in overtime has also been observed. The maximum legal amount of overtime per worker, which was, up until recently, 120 hours, is today between 360 and, for jobs such as transport, 750: hours. At the same time, in accordance with recent decrees, the statutory 42-hour week will now exist within 1 a more flexible framework allowing the standard, 8-hour working day, for certain categories of workers to be ex tended by up to 4 hours by management. And in certain plants, any extra hours would count exclusively as paid overtime and not count toward compensatory free time.

“He or she who doesn’t strike, doesn’t eat and works too hard,” proclaims the newspaper of Solidarnosc members at the Lenin steelworks in Nowa Huta. But Solidarnosc does not have any system of immediate and partial demands, not to mention a transitional strategy.

In 1985, the national leadership of Solidarnosc initiated two big campaigns: (1) for the boycott of the elections to the Diet; and (2) against the price increases. Zbigniew Bujak and Jacek Kuron justified these campaigns as a means of pressure on the government to accept elections that would be a little more democratic and be forced to carry out an economic reform of a fairly hazy character.

These campaigns were not conceived as a means of building the strength of the workers, elevating their level of organization and preparing a new wave of mass movements, even though this would be a logical step. Instead, the programmatic conquests of Solidarnosc were diluted. The old project of workers’ self-management and of a system of economic management that–as defined by Solidarnosc’s National Congress in Autumn of 1981–would “combine the plan, self-management, and autonomous bodies without any real connection with the market,” gave way to the discourse of intellectual experts in the leadership of Solidarnosc over the supposed merits of the market economy.

The aspirations of the working class, meanwhile, have enormous difficulties in being expressed due, among other reasons, to the fact that the clandestine leadership of Solidarnosc has weakened its ties with the workingclass base and has begun to rely primarily on dissident intellectual sectors.

At the end of 1984, a team of sociologists from the University of Poznan took a poll among a sample of personnel, primarily blue collar workers, from four large factories in heavy industry situated in different regions of the country. Questions about what ideal social system workers would support elicited a 78 percent response in favor of truly democratic parliamentary elections involving several voting lists; 65 percent in favor of several concurrent political parties; 80 percent in favor of free speech for all people, including both the supporters and opponents of the political system. 58 percent were in favor of social ownership of the means of production and a planned economy, while 87 percent favored full workers’ self-management! One of the underground newspapers that published the results of the poll pointed, in its analysis, to the clear aspiration of Polish workers for a “different system of humane, democratic socialism.”(1)

But this poll reveals a serious contradiction as well: a very strong working-class loyalty to the democratic and self-management traditions of Solidarnosc is accompanied by the support of barely 20 to 25 percent of workers for the underground activities of Solidarnosc. A similar percentage of workers, in the same poll, are partisans of the regime. This means that half of the workers, more or less, while hostile to the regime, do not identify with the structures and the actions of the social movement as it presents itself today.(2)

The struggle for state power must lead to the use of force. In the struggle for a Self-Managed Republic, announced in the resolution passed at the memorable Solidarnosc Congress in Gdansk in Autumn 1981, the use of force must be renounced, stated Adam Michnik in a letter from prison. Michnik never clarified how it is possible to struggle for a Self-Managed Republic without fighting for state power.(3)

The militants of the democratic opposition, whose most prestigious spokespersons are Kuron and Michnik, today exercise a real ideological hegemony over the leadership of Solidarnosc. This opposition, flowing from the old Workers’ Defense Committee (KSS-KOR), has an orientation that can be more or less characterized as social democratic. (Kuron, as well as Karol Modzelewski, renounced the revolutionary program inscribed in their famous Open Letter of 1964. A few short years after its appearance, they renounced Marxism in general as well.)

Kuron, Michnik, and their comrades tirelessly and with a faith worthy of a better cause repeat that the alternative for the Polish social movement is to be either an angry mob that carries out street lynchings or an organized society capable of making compromises with the State. We must do everything in our power to make compromise possible in order to create a hybrid system that will be a cross between the totalitarian power of the State with the democratic institutions of society. Why? Not only because the USSR has such enormous military power that confrontation is simply unthinkable, they explain, but also because liberty conquered through a revolution, that is to say, in a violent fashion, always and inevitably becomes a refugee from the camp of the victors.

Michnik fully develops this argument in the above-mentioned letter, in which he does not hesitate to raise the specter of “the cruelty of rebellious mobs lynching the hated functionaries” during the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. The most authoritative socialist historian from this revolution, Bill Lomax, points out that this is a myth created by the right-wing Western press and that the data published even by the Kadar government “establishes the Hungarian revolution as one of the most bloodless revolutions of all time”(4)

What is hidden behind this position of Michnik and his comrades if not a deep distrust in the working class and its independent action, a very characteristic distrust for the democratic intellectuals? Members of the Polish democratic opposition, nevertheless, continue to hold on to their myths just a few years after Poland experienced an impressive revolution based on the self-organization of ten million workers, which made mincemeat of the reactionary myth that revolution is a street lynching by angry mobs. The result is that, out of the “strategy of the self-limiting revolution” foreseen by these militants, much remains today of the self-limitation, and, in the best of cases, little of the revolution. This continues to be the fundamental cause of the impasse in which Solidarnosc finds itself.

From the Union of the Workers’ Councils to the Workers’ Opposition

Already by the end of 1983 an organization had been formed, at the time limited to a single region, that marked the beginning of the regroupment of a revolutionary workers wing of the social movement. It was the Union of the Workers’ Councils of the Polish Resistance (ZRP-PRO) of Upper Silesia, situated in one of the larger industrial centers in the country.

The leaders of this organization, blue-collar workers, say that in particular three experiences influenced their process of political definition. The first two go back to 1982. Following Jaruszelski’s coup, a defense committee for the jailed and persecuted members of Solidarnosc, initiated by the future leaders of the ZRP-PRO, was formed in Upper Silesia. The committee collaborated with the parishes of the Catholic Church, which delivered humanitarian aid from the outside. Some priests refused to aid the common-law wife and “illegitimate” son of an imprisoned militant, and wanted, in general, to impose their own criteria on the distribution of material aid. The committee reacted by separating itself from the Church.

At the end of 1984 and the beginning of 1985, two events happened that led the ZRP-PRO to adopt an openly critical attitude toward and to act completely independently of the leadership of Solidarnosc, without thereby renouncing the united front. Under the pressure of the Western trade-union bureaucracies, the national leadership of Solidarnosc refrained from solidarizing itself with the strike of the British miners. Further, in Upper Silesia, the leadership unleashed sharp attacks against the Solidarnosc miners’ committee, which, in its clandestine radio programs and in its messages to the British miners’ union NUM, had proclaimed its support for this strike and denounced the Polish bureaucratic regime for having increased its coal shipments to the Thatcher regime. The argument they advanced was that, through this strike, the Stalinists were trying to destabilize a democratically-elected regime. In this debate, the ZRP-PRO placed itself on the side of the British miners and opposed the attitude of the Solidarnosc leadership.

In the same period, the latter launched a call for a national strike of 15 minutes to protest the price increases. At the last minute, believing that the government was willing to rescind the increases, which turned out not to be true, Lech Walesa and Zbigniew Bujak called off the strike. This produced disorientation and demoralization among the workers. Further, the ZRP-PRO, took the risk of uncovering too many of its cells in the factories to better prepare the strike. These remained open to repression.

The base committees of the ZRP-PRO, which called themselves underground workers’ councils, existed, according to data from the end of 1985, in more than twenty large factories, mines, forges, transport enterprises, etc. In a report of its leadership, it was stated that “this organization is now the largest workers’ organization in Upper Silesia, solidly implanted in important enterprises of several cities, as well as better prepared than others for the general strike and for the seizure of factories by the workers.” It had led numerous mass actions-for the boycott of the regime’s unions, for the withdrawal from the legal workers’ councils obedient to the administration, for wage and benefit increases, against poor working conditions (organizing, among other things, health and safety strikes).

According to a report from the leadership of the ZRP PRO at the end of 1985, 70 percent of the members of this organization were blue-collar workers, almost 90 percent had a technical or secondary education, and more than 80 percent were younger than 30. More than a third had not belonged to Solidarnosc before December 1981 because they were too young. It is interesting to note that not one intellectual was part of the leadership. This data says a lot about the sectors that are corning forward today, the composition of the workers’ vanguard of the social movement, and its capacities for renewal.

The political positions of the ZRP-PRO were, from the beginning, very different from the Solidarnosc leadership: its objective was to build clandestine cells that, with a new rise of the mass movement, would be able to assure a leadership of a mass strike with occupations, establish workers’ power in the enterprises, and, on this basis, follow the road of the revolutionary overthrow of the bureaucratic regime. The central strategic end was definitely clear: the conversion of the fundamental means of production into truly social property, that is to say, the collective democratic management of the means of production.

“The ZRP-PRO,” we read in its 1983 declaration, “adheres to the following five points: the factories to the workers, the land to the peasants, power to the selfmanaged society, science to free thinkers, the state for an independent nation. To achieve these objectives, it is essential that society organize itself and assure freedom of action for political parties, that trade-union pluralism be established, that a free parliament be elected through free elections and that it exercise control over the state apparatus ….In its work, the ZRP-PRO takes inspiration In the same period, the latter launched a call for a national strike of 15 minutes to protest the price increases. At the last minute, believing that the government was willing to rescind the increases, which turned out not to be true, Lech Walesa and Zbigniew Bujak called off the strike. This produced disorientation and demoralization among the workers. Further, the ZRP-PRO, took the risk of uncovering too many of its cells in the factories to better prepare the strike. These remained open to repression. The base committees of the ZRP-PRO, which called themselves underground workers’ councils, existed, according to data from the end of 1985, in more than twenty large factories, mines, forges, transport enterprises, etc. In a report of its leadership, it was stated that “this organization is now the largest workers’ organization in Upper Silesia, solidly implanted in important enterprises of several cities, as well as better prepared than others for the general strike and for the seizure of factories by the workers.” It had led numerous mass actions–for the boycott of the regime’s unions, for the withdrawal from the legal workers’ councils obedient to the administration, for wage and benefit increases, against poor working conditions (organizing, among other things, health from the best traditions of the workers’ struggle and their revolutionary assaults on power. It supports the struggle of the working class to win social identity and national independence in the countries under the domination of the totalitarian bureaucracy, especially the working class of the sister peoples of the German Democratic Republic, Czechoslovakia and Ukraine. It upholds proletarian internationalism in all its dimensions ….It regards as enemies and hostile to the interests of the working class any organization that opposes the right of the working class to ownership of the enterprises and will treat them in the same way that it treats the totalitarian bureaucracy ….It does not recognize the right of nonworking-class organizations of a general social character to represent the interests of the working class.”(5)

In the course of its evolution, the ZRP-PRO established its collaboration with revolutionary socialist militants grouped around the underground publications Front Robotniczy (Workers’ Front) and Sprawa Robotnicza (Workers’ Cause). It was on this basis that, in June 1985, the Alliance of the Workers’ Opposition (POR) arose, which rapidly surpassed its initial framework. With the joining of new groups, its cells appeared in dozens of cities. The name chosen underscored its political identity with respect not only to the “independentist opposition” (nationalist currents, “Catholic-Nationalists” and “democratic liberals” who, in general, had abandoned the ranks of Solidarnosc in the last few years, breaking with the workers’ movement), but also the democratic opposition. Stating that the political struggle developing in Poland is, above all, a class struggle, the POR explains in its platform:

“It is essentially a struggle between the working class, which is subjected to economic exploitation and deprived of all political or economic power, and the bureaucratic state power Only the working class has the capacity to overthrow the bureaucracy, and it is only thanks to it that the social groups can liberate themselves from the yoke of the bureaucracy. . . The transformation of the working class from an object into a subject is only possible through revolutionary changes. The belief in the possibility of a compromise with the bureaucracy is a dangerous illusion that could prove fatal.”

In its predictions about how the bureaucratic power can be overthrown, the POR places special importance on three factors: First, a general revolutionary strike, which has a tendency to become an “active strike,” that is to say, a work-in strike (such was the project of the radical Solidarnosc leadership in Lodz at the end of 1981); second, the formation of workers’ guards, whose principal task consists of assuring the active defense of the factories seized by the workers; third, it states that “it is only under such revolutionary conditions that we could expect a part of the army, primarily ordinary soldiers, when they see that the workers’ forces have a chance of success, to join in the uprising of the working class.”

The strategic objective of the future Polish revolution, which the POR characterizes as a democratic workers’ revolution, is the establishment of a Self-Managed Republic. “The indispensable precondition for the liberation of the working class is for it to lay the economic foundations of its liberty, that is, socialization, outside of the state and in the framework of a system of workers’ self-management, of the means of production that are today statized.” Outside of the state means not through the bureaucratic apparatus of the state, which must be destroyed in the course of the revolution, but rather through the power of workers’ councils in the enterprises “linked together by horizontal and vertical structures on the regional and national scale, as well as institutions of self-management organized on a territorial basis Selfmanagement can only function in conditions of unrestricted political pluralism.”(6)

Defending Living Standards and the National Economy

At the beginning of 1986, in several neighborhoods of Praga–part of Warsaw that lies on the right bank of the Vistula River–all the residents found a flier put out by the POR that called for the initiation of rent strikes, that is to say, the refusal to pay the increased rents. Since the spring of 1985, there had been a dizzying rise of rents, which, in extreme cases, went as high as 600 percent. This is due to the fact that, in the framework of the “economic reform,” housing cooperatives are no longer subsidized by the state and must finance themselves.

This is just one of the aspects of the housing crisis that the country is experiencing. At least 10 percent of Poles are on waiting lists for cooperative apartments, the predominant form of residential construction in urban areas. The waiting periods for housing are probably the longest in Eastern Europe-Poles can expect to wait for between 20 and 30 years to be assigned an apartment. The existing housing is overcrowded-Poland’s household/housing unit ratio trails behind the majority of mid- and poorlydeveloped European countries. Construction rates have fallen by a third since 1978 and there is no sign of any improvement. According to the official estimates, it will take 30 years to satisfy the existing need. The time has passed-some of the more cynical bureaucrats did not hesitate to declare-for “the view that someone deserves an apartment simply because he was born in a socialist country….”

The massive distribution of the POR’s leaflets, which instructed city residents how to carry out a rent strike and how to unify their demands, was the first initiative taken by the Polish social movement on this very explosive terrain. Other active groups of Solidarnosc in the neighborhoods of Fraga first watched incredulously at the appearance of the fliers and their social echo. Then they made a united front with the FOR, helping it in the printing and distribution of the fliers. Barely several weeks later, rent strikes broke out in the Targowek neighborhood of Fraga.

The rent strikes, according to the program of struggle of the FOR, should serve as an opportunity to form independent neighborhood committees. These committees would concern themselves with overseeing the distribution of housing by the authorities and revealing the existence of empty units and of excesses in order to exert pressure on the bureaucracy and oblige it to carry out a more socially just policy on this level. They could also protest the insufficiency of the children’s centers and the laziness of the housing administration; head up the struggle for housing allocations for people who live in bad conditions; organize the collective purchase of food directly from the farmers, where prices are lower than in the supermarkets, etc. Further, the FOR calls for such committees to collaborate with independent workers’ organizations in the nearby factories.

It is characteristic of the POR’s program that its revolutionary strategy is based on the self-organization of the working class and other oppressed social groups. “Every battle, even on the most limited question,” it states in its platform, “bears within it an embryo of the future revolution, inasmuch as it contributes to the self-organization of the workers.”

The starting point of the POR’s class struggle program is classic: it is the demand for the sliding scale of wages. A traditional demand in Poland since 1979, when it opened the first program of the independent workers’ movement, the Letter of the Rights of Workers, it was elaborated by sections of the democratic opposition. For the POR, this demand must today be the central axis of the mass struggle, a different attitude from that of the Solidarnosc leadership, which, in fact, does not carry through systematic campaigns of mobilization around the sliding scale. The FOR believes, on the other hand, that this demand translates on an organizational level into the formation of statistics commissions in the enterprises (such commissions existed in the Polish workers’ movement during the crisis of the 1920s, especially in Upper Silesia) that initiate the struggle for the sliding scale.

In many other areas of social life, from the situation of youth in families with many children, those who live in the worst conditions, etc., the POR raises a demand for a specific social allocation as well as the principle of its automatic cost-of-living adjustment as a means of defending living standards.

“Our struggle in defense of living standards, even though it has a primary importance, would hardly be effective or complete if it weren’t accompanied by a struggle in defense of the national economy. . . Around us, idiotic wastes abound: the work of the bureaucracy, economic irrationality carried to absurd extremes, criminal economic decisions (the violation of laws, the use of the means of production and administrative positions for private ends, the scandalous abandonment of machines and equipment that are worth a lot, the violation of the norms of health and safety on the job, worsening the health of the workers, etc.). But these are our factories! We must not allow the destruction of our property, because the more the bureaucracy destroys, the less they will have to share with us, the society. We have to protest at every step the irrationality and the economic sabotage of the bureaucracy–denounce, protest, accuse the officials before tribunals and, if it is necessary, conduct strikes in defense of our factories, of our common national patrimony. The less the bureaucracy wastes, the more there will be for us, and the more rapidly it falls from power, the less will be wasted. Just look at the hands of the bureaucracy!”(7)

This is another aspect of the FOR struggle current’s program, which calls on the workers to substitute independent workers’ control for the fictitious technical control by the bureaucracy over the quality of production, to demand a rational organization of labor, to reveal the economic data, fighting “commercial secrets” and the falsification of the statistics that cover up bureaucratic parasitism, etc. The POR believes that the tasks in this area could be assumed by those official workers’ councils that, under the pressure from the workers, have been democratically elected and which enjoy their confidence.

The FOR also promotes the formation of independent commissions of workers’ control, of health and safety on the job, etc., which could become a type of “shadow cabinet” of the future workers’ power in the enterprises, together with other underground workers’ institutions: the political defense commissions, the “boxes of resistance,” including the workers’ guards commissions that could today elaborate “plans of defense of the enterprises (how to come together and where to place the antitank barriers, how to block access, how to use industrial equipment and tools as means of defense) in anticipation of the future sit-down strike.”

The combination of the defense of workers’ living standards together with the defense of the national economy against bureaucratic power constitutes the foundation of the entire transitional program of the POR. This is due to the POR’s position that “this state and this economy belongs to the working people of the city and countryside,” but given the “existence of a dictatorship… over the working population, property as well as power are structurally alienated,” under “the totalitarian control of a usurping bureaucratic layer.” There remains no other solution for the working class, the POR declares, than “to take our property by force and our power” from the hands of the bureaucracy.

The POR is not, nor does it aspire to become, a political party. It considers itself to be a revolutionary class struggle current of the social movement Solidarnosc. At the same time, the POR does not consider itself a substitute for a political party. Many of its militants are convinced that in order for the working class to “win the right to a life with dignity and to socialism,” as they put it, in order to overthrow the power of the bureaucracy, establish a self-managed republic and assure the revolution of its international character, a revolutionary party is necessary. These militants have decided to build it. It is for that reason that, as a formation in transition in this direction, Political Groups of the POR have arisen in Warsaw, in Upper Silesia and in some other places.

Some currents of the British revolutionary left complain that the POR is not “an embryonic revolutionary party,” that it “makes revolutionary sounding propaganda, but is unclear about what is needed to overthrow the system” and that an “explicit call for a party to lead the struggle is missing from the program of the POR.” One of the leaders of the POR has responded that for him and his comrades it is not a matter of proclaiming such a party, but rather of building it, raising the work of the masses to a higher level, without substituting other indispensable forms of organization of the workers.

For International Working Class Solidarity

“The Polish working class,” states the POR in its platform, “is not isolated in the struggle. It has friends and allies abroad. They are the workers of the entire world. The Polish workers’ movement can and must draw on the strength of international workers solidarity. The differences between East and West cannot hide the fact that the workers of both camps are linked by common interests, by a common struggle for a common end-the transformation of the working class from object into subject–against common enemies. The question of international solidarity is one of close cooperation of the various national contingents of the revolutionary workers movement. It is one of interaction between the development of the class struggle, for example, in Poland, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain.”

When the POR holds that the totalitarian bureaucracy, nationally as well as in the Kremlin, is a class enemy, it does not conceive of it only as an enemy of the Polish working classes and the other countries of the socialist bloc, but rather as one of the mortal enemies of the world working class. It is very important to understand the sense of this message.

The birth of societies in which capitalism, or as some revolutionaries prefer to say, private and corporate capitalism, has been overthrown, but where a system of totalitarian bureaucratic power has taken its place, has created a radically new situation for the international workers movement.

Bourgeois imperialism initiated two types of division into the workers’ movement: first, the division between its national components in the different imperialist countries, which were set against each other behind their own bourgeoisies; and, second, between the workers’ movement of the imperialist countries and that of the dependent countries.

Stalinisrn in power has introduced a third division, no less effective. In the capitalist countries, the bourgeoisie disarmed important parts of the working class, showing them the Soviet bloc as proof that “After me, the gulag.” Other parts of this class, to the contrary, continue to believe in even the claimed superiority of “really existing socialism” and the “proletarian conquests” which are supposedly contained in it. They turn their back on the working class and the dissidents of the countries to the East. Even in the workers’ revolutions, such as in Hungary and Poland, they see a bourgeois counterrevolution instigated by Washington, the Vatican, etc.

In Poland, the democratic opposition and broad circles of Solidarnosc sport a kind of replica of this same image. The world is divided for them into totalitarian and democratic countries. The Central American revolution or the strike of the British miners are the work of the Kremlin or, at least, serve its interests. Poland’s fate is entwined in a world conflict, but this conflict, states Michnik, is a superpower conflict. Michnik’s conclusion: Solidarnosc members do not expect any support from outside and “are perfectly aware (and willing to say this to others) that they must, and will, count only on themselves.”

Michnik and his comrades reinforce this conclusion by adding the famous saying of a Soviet dissident: “We are neither from the left camp, nor from the right camp, we are from the concentration camp,” even though it is a completely false idea which Michnik probably does not think is true, since, on several occasions in the not distant-past, he defined himself as a man of the Left.

It does not surprise me that such an idea comes out of the prisoners of concentration camps. But these camps are in the USSR, not in Poland. Poland’s fate is entwined, obviously, in the struggle of the world working class against its oppressors and exploiters, whether they are called bourgeois or bureaucratic. This is the position of the Polish revolutionary left and is clearly expressed by the POR. We have to realize that workers’ revolutions of the East are not second class with respect to workers’ revolutions of the West.

A revolutionary socialist in the East-the author of these lines .can serve as a witness-is questioned a lot in the West on his attitude toward the liberation movements of oppressed nations in the so-called Third World. And rightly so. If only those who ask the questions would consider, similarly, how fair is it to completely ignore the fate of the oppressed peoples of the USSR, despite the fact that the USSR, today, is the largest prison of nations in the world. The cause defended by the Irish Republican Army is not essentially different from the cause that, in the 1940s, was defended by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army–two movements on the same continent, the former known to everybody, and the latter, known barely to anyone, even though up until today its former fighters continue to be shot in the USSR. Everyone remembers, for example, the Algerian insurrection of 1954 and almost no one the insurrectional strikes of the concentration camp prisoners in the USSR and the East German workers in the summer of 1953.

Let’s take a recent event into account. Against the orientation of the Solidarnosc leadership, some workers’ committees, political groups, and newspapers of the Polish social movement expressed their solidarity with the British miners’ strike and denounced the tacit alliance established on this occasion between Jaruzelski and Thatcher. As on several previous occasions—for example, many years ago during the strike of the Spanish miners in Asturias under the Franco regime–the Polish bureaucratic regime increased its shipments of coal to Great Britain, placing the miners in a difficult situation.

The NUM and its president Arthur Scargill personally received letters from Solidarnosc from Poland. The text of the message broadcast by the underground radio of the miners of Upper Silesia was published in Great Britain. Scargill energetically denounced the government of Jaruzelski and considered the attitude of the official Polish trade unions to be hypocritical. The NUM pickets attacked the Polish embassy in London; 8,000 pickets had a big battle with the police in Orgreave in order to stop the shipment of Polish coal from reaching the coal industry. But Scargill, who, after December 1981, came out against Solidarnosc and for Jaruzelski’s coup, did not change his position with respect to Solidarnosc.

The messages coming from Poland had an echo in the British revolutionary left and in the social democratic left of the Labour Party. Nevertheless, no section, not even a local of the NUM, made the faintest echo, not to mention a small gesture of reciprocity. A half-year after the end of the strike, one of the currents of the British revolutionary left commented: “Scargill seems to have learned nothing from the miners’ bitter experience with his scabbing Polish ‘socialist’ comrades. Scargill is now in Moscow setting up an international organization of miners–which will include the fake miners’ unions of countries like Russia ….Militant miners … should tell Arthur Scargill to stop hobnobbing with the anti-working-class scab unions of the Stalinist police state.”(8)

The leaders of the British NUM persist in not understanding that if the British miners go out on strike again some day, and Polish coal isn’t shipped, it will be by the decision of the independent workers’ movement of Poland, that is to say, of Solidarnosc, and not by a decision of the Polish bureaucracy and its “unions.” Revolutionary socialists must develop an overall appreciation of the NUM strike that takes into account the NUM’s attitude toward Solidarnosc just as, obviously, we must insert the attitude that the Solidarnosc leadership took toward the NUM strike in a balance sheet of the struggle of the Polish social movement.

There are other problems that are posed for unions controlled or influenced by social democracy which, in the current configuration of the organized mass workers’ movement in the capitalist countries, are those which must insure more support to the struggle of underground Solidarnosc. The leadership of a part of these trade-union, organizations have shown themselves to be ready to deliver significant support, but, at the same time, they wish the real nature of Solidarnosc, its forms of struggle and organization, its mass democracy, its fight for workers’ self-management, and its project of building a Self-Managed Republic to not be known among their ranks, in other words, among those who are the likeliest to ignite a more spontaneous and combative defense of the workers of the West.

What happened with the trade unions in West Germany was the worst. Because of its geographical situation and organizational and material potential, they should logically have been the strategic rearguard of Solidarnosc. Nothing of the sort. “We have the greatest problems with the West German DGB; we have practically no contacts with them,” declared Zbigniew Bujak several months before his capture. “I believe this is the result of the SPD’s (German Social Democratic Party) policy of emphasizing relations with the officialdom of People’s Poland and of almost completely bypassing Polish society, its far-reaching independent social life, its leaders, and its aspirations.”(9)

There are many in the West and in the East who take seriously the statements of the leaders of U.S. imperialism in support of the social movements such as Solidarnosc or, in general, of the fighters for human, civil, and workers’ rights in Eastern Europe and in the USSR. Among those who believe in these declarations, there are those, in the East, who see allies in the rulers of the White House, just as there are those in the West who, for the same reason, see an enemy in Solidarnosc.

But beyond the words, we have to look at facts. The U.S. government abstained from sending arms to the Ukrainian nationalist guerrillas in the 1940s(10) or to the fighters of the Hungarian revolution—a matter that is fully described by David Irving, a right-wing British historical of this revolution.(11) Today the Washington Post reveals that Ronald Reagan personally knew details of the preparations for the Polish bureaucracy’s attack against Solidarnosc more than a month prior to the date of the coup. Nevertheless, the U.S. government failed to warn the leadership of Solidarnosc.

A good Indian is a dead Indian, as the American officers said who more than a hundred years ago conquered the Far West. A good anti-Stalinist revolution is a smashed revolution, their successors seem to say. It is thirty-five years ago already that an American socialist, Hal Draper, explained well the attitude of the rulers of the White House, writing on the future revolution in the USSR and, by extension, on its prologue, the revolutions in the satellite countries of Eastern Europe:

“The new Russian revolution will have to be a socialist revolution, by virtue of the fact that it is a democratic revolution in a collectivized system. The state now owns all the means of production; the new Russian revolution will give the state power back to the ‘ownership’ of the people. The clock cannot be turned back to the old capitalist system which is decaying everywhere in the world. And such a democratic socialist revolution in Russia would spell the final end of capitalism everywhere in the world-as the Russian revolution of 1917 almost did. That is the basic reason why responsible and intelligent capitalist policy, in today’s world, finds it dangerous to play with the fire of revolution behind the Iron Curtain.”(12)

There are those who believe that the rulers of the Kremlin support anti-imperialist and anticapitalist revolutions, because they see that they send arms to a country like Sandinista Nicaragua. Especially among the fighters in the national and social liberation movements of the “Third World,” there exist illusions that the totalitarian Soviet bureaucracy is its ally. Meanwhile, many dissidents in the East reproduce the same illusion in their own way: they see in these revolutions agencies of Moscow.

Again, we have to go beyond appearances. Another American socialist, Joseph Hansen, explained once very well that the greatest single obstacle to a socialist victory in the capitalist countries, in particular, in Western Europe and the United States, is the reversion of the USSR to a precapitalist level so far as democracy is concerned and the totalitarian image conferred on socialism by the Stalinist regime. “If there is one thing needed to counteract this lie of socialism and Stalinism being one and the same thing, it is an example of socialist democracy in practice.”(13)

As real as their mutual hostility is the terrible fear both Washington and Moscow have that such an example will arise. And in this area, objectively, there exists between the systems of rule of the bourgeoisie and the bureaucracy a holy alliance. Socialists, revolutionary nationalists, the militants of the workers’ movement and of the movements of national liberation have the responsibility of understanding that, at least for the past halfcentury already, since the bourgeoisie and the Kremlin oligarchy joined hands to crush the proletarian Spanish revolution, this alliance has existed.

The young Polish revolutionary left, grouped together in the Alliance of the Workers’ Opposition, has a clear position: the victory of democratic and international socialism can be won only by a workers’ movement that is able to fight united and in solidarity against the domination of the working class and the subjugation of peoples by both bourgeois imperialism and the totalitarian bureaucracy, “to overthrow the rule of capital in the West and the South and the power of the Nomenklatura in the East.”

Footnotes

- Obecnosc (Wroclaw) no. 10, 1985.

back to text - Tygodnik Mazowsze (Warsaw) no. 157, 1986.

back to text - In English, see Adam Michnik, “Letter from Gdansk Prison,” The New York Review of Books, July 18, 1985.

back to text - London: Allison & Busby, 1976, pp. 123-28.

back to text - For the text in English of the “Ideological-Political Statement of the ZPR-POR” see International Viewpoint (Paris) no. 100, 1986, and no. 89, 1985, or Socialist Worker Review (London) no. 84, 1985.

back to text - For the English text of the “Draft Platform of the Workers’ Oppostion” see International Viewpoint (Paris) no. 89, 1985, or Socialist Worker Review (London) no. 84, 1985.

back to text - Special issue of Przelom, 1986 (Central organ of the POR). See Socialist Workers Review, (London) no. 84, 1986, and Socialist Viewpoint, (London) no. 10, 1986.

back to text - Jack Cade, “Another Apology Needed,” Socialist Organizer, (Lon don) no. 243, 1985.

back to text - Tygodnik Mazowsze (Warsaw) no. 152, 1986.

back to text - See my article “Deny your Father, and you go free,” Socialist Organizer (London) no. 271, 1986, also published in International Viewpoint, (Paris) no. 100, 1986.

back to text - David Irving, Uprising! London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1981).

back to text - Hal Draper, “Washington and the New Russian Revolution,” Labor Action, June 11, 1951.

back to text - Joseph Hansen, Dynamics of the Cuban Revolution, New York: Pathfinder Press, 1978, pp. 376-77.

back to text

4. Bill Lomax, Hungary

September-December 1986, ATC 4-5