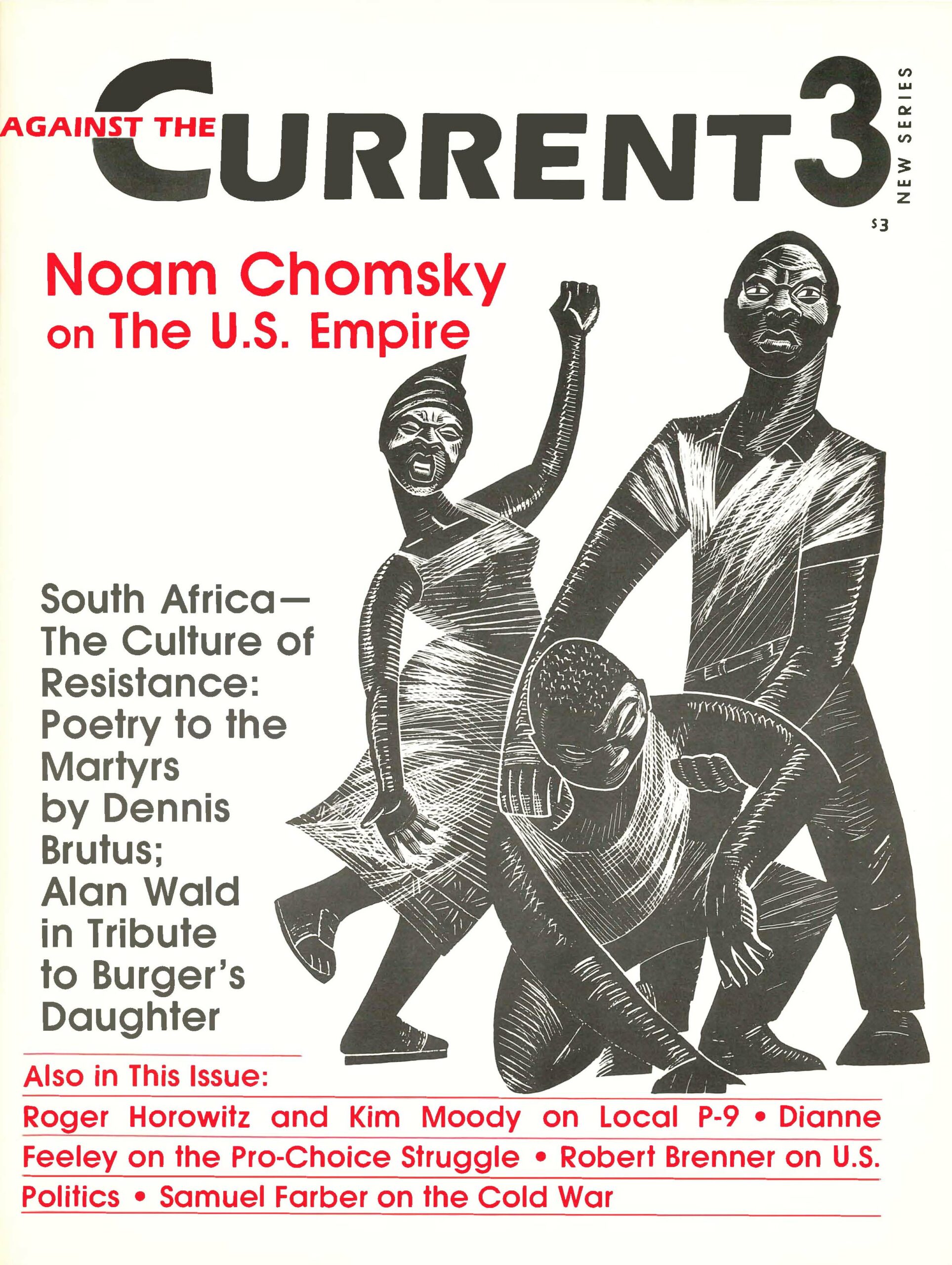

Against the Current, No. 3, May/June 1986

-

Letter from the Editors

— The Editors -

Abortion Rights: Contested Terrain

— Dianne Feeley -

Defend Our Gains, Move Forward

— Ann Menasche interviews Helen Grieco & Debbie Greg -

Debate in Labor Growing as P-9 Strikers Continue the Battle

— Roger Horowitz & Kim Moody -

Life After Trusteeship

— Roger Horowitz & Kim Moody - Wynn Bombs Austin, Hits Soup

-

In Tribute to "Burger's Daughter"

— Alan Wald -

Poems for the Martyrs

— Dennis Brutus -

The Empire and Ourselves

— Noam Chomsky -

Austerity & Interventionism: Political Effects of Economic Decline (Part 2)

— Robert Brenner -

A Comment on the Cold War

— Samuel Farber - Letter & Response on Pornography

-

Random Shots: Mary Jane's Magic Dust

— R.F. Kampfer

Samuel Farber

IN THE COURSE of his wide-ranging and in some respects valuable critique of E.P. Thompson’s theory of exterminism (“Nuclear Imperialism and Extended Deterrence,” Against the Current, old series, Winter 1985), Mike Davis presents an analysis of U.S.-Soviet conflict which is seriously flawed, in my view.

Aspects of Davis’ approach reappear in James Petras’ recent article, “Summit Politics and the Third World” in Against the Current, new series, #2. (My concern with Petras’ article is limited to its point of convergence with Davis’. I don’t dispute his cogent and valuable observations on U.S. policy in Haiti, the Philippines, and so forth.)

I do not contest a major thrust of both articles, which argue that a primary source of the breakdown of detente and the U.S. military buildup lies in revolutionary challenges to U.S. hegemony in the Third World. However, I disagree with the way in which both articles theorize the connection between U.S.Soviet relations and U.S.-Third World relations. In particular, they tend to downplay, if not ignore, the imperialist actions and aspirations of the Soviet Union.

In analyzing the Cold War several questions must be clearly identified. These include: 1) the origins of the Cold War; 2) its present central dynamic; 3) how the Cold War relates to strategies of U.S. domination in the Third World; 4) what are we, as revolutionary socialists, to say about the Soviet Union’s role within its own, smaller, sphere of dominance? It is this last question which I wish to primarily address in commenting on Petras’ and Davis’ articles.

While neither article is primarily concerned with an analysis of the power of the Soviet Union outside its own boundaries, I feel it is imperative to take up this question, because it is so central to supporters and members of the democratic and workers’ movements in Eastern Europe (e.g. Polish Solidarity). The political credibility of the Western left with these groups depends on the approach we take toward the Soviet Union. In his critique of Thompson’s “exterminism” and “the current common sense of the peace movement,” Davis proposes:

“It is necessary, in my opinion, to reinstate the revolutionary Marxist conception of the modern epoch as an age of violent, protracted transition from capitalism to socialism. From this perspective the Cold War between the USSR and the United States is ultimately the lightning-rod conductor of all the historic tensions between opposing international class forces, but the bipolar confrontation is not itself the dominant level of world politics. The dominant level is the process of permanent revolution arising out of uneven and combined development of global capitalism. This is the true motor of the Cold War.” (p. 25, emphasis in original)

The imagery and analysis here are rather hazy and readers can draw their own conclusion as to Davis’ meaning. In my view, Davis leaves us with the conclusion that, since the U.S. certainly represents the bourgeoisie in the “tensions between opposing international class forces,” the USSR must represent the proletariat.

Elsewhere in the article, Davis does argue that “[T]he Soviet Union’s role in world politics as the material and military cornerstone of further subtractions from the empire of capital has been largely involuntary.” (p. 25) This qualification, however, only reinforces the thrust of Davis’ argument which is to characterize Russian interventions as primarily responses to U.S. attempts to “enforce its geopolitical and military paramountcy.” (p. 27) Russia is depicted as a purely reactive power, defending itself and others against the Western onslaught.

In this regard, Davis states that the greater suffering of the Russian people compared to the American people, especially during World War II, “helps us to make certain predictions about the behavior of these two great powers” (Davis’ emphasis, p. 24), i.e. the greater reluctance of the Soviet Union to risk a war.

He argues that the Russian takeover of Eastern Europe after World War II was simply self-defense, “Stalin’s determination to create a protective glacis round the USSR.” (p. 26) The Soviet Bloc “emerged, not out of a grand design for a world order, but as the accretion of battered and besieged socialisms in one country, huddled together for sheer survival round the preponderance of the first comer.” (p. 27) Developing this point further, Davis argues that the significance of the EastWest divide in Europe has been, at least since 1950, primarily ideological:

“[T]he official history and ideology of the West has always magnified Europe as the central arena of the Cold War, because it was there that political and economic contrasts worked in its favor, that capitalism enjoyed a moral and cultural superiority, and that the USSR could be portrayed as a national oppressor.” (p. 27)

Davis leaves it totally ambiguous here whether the USSR is a national oppressor, or merely “portrayed” that way in Western propaganda. It seems to me we cannot afford this kind of sloppy formulation–certainly no Pole, no Czech dissident, and for that matter no principled Russian democratic activist would tolerate it. Overall, Davis’ approach is far too similar to those formulations with which the Left has historically alienated the best elements in Eastern Europe.

An Imperialist Rivalry

Without in any way pretending to offer a full analysis of the Cold War, I would like to present an alternative picture. The Cold War is the product of inter-imperialist rivalry of two hostile social systems, although the imperialism of the USSR is of a different kind than that of modem capitalist imperialism.

Note that in his analysis of capitalist imperialism, Lenin never made the absurd claim that imperialism had only existed under modern capitalism, although his concern was, of course, to explain the capitalist imperialism of his day.

Soviet bureaucratic imperialism is still significantly weaker and smaller than U.S. imperialism, and this necessarily forces a certain degree of caution on the Soviet leadership. However, this general rule of caution does not always apply to Soviet actions (witness, for example, Khrushchev’s willingness to place missiles in Cuba in the early sixties). Soviet imperialism is not pro-socialist in any democratic or working-class sense, but it is anticapitalist (which naturally does not preclude tactical and even strategic agreements with one or more capitalist powers).

In part because of its anti-capitalism and in part because of its relative economic and military weakness with respect to U.S. imperialism, the USSR often attempts to politically ally itself with actual or potential anti-capitalist movements, especially in the less stable countries of the Third World.

It goes without saying that this political support and alliance entail a certain degree of economic and military commitment as well, and that in some individual cases such as that of Cuba, this economic and military commitment can be quite considerable.

Here, many leftists wax enthusiastic at how the Soviet Union has helped to preserve “socialist” revolutions from U.S. imperialist attacks. I would, however, make quite a different point: namely, that the political attraction of the Soviet model (in any of its national variations) for certain declassed and petty-bourgeois educated strata in the Third World, combined with the considerable material resources of at least the USSR, has helped to preserve not socialist but Stalinized revolutions.

Furthermore, the Stalinization of these revolutions (e.g., Vietnam, Cuba) is not a process independent from the previous existence of the Russian Soviet model and the availability of Russian material aid. This also complicates, if it doesn’t diminish, the likelihood of success for democratic revolutionary socialist tendencies in Third World revolutions.

In the light of the very real threat posed by the Western imperialist powers, Stalinist tendencies and groupings, by no means limited to the old and discredited proMoscow Communist parties, are able to obtain at least temporary acceptance if not popular support by posing as the only “realistic” alternative.

The bipolar US-USSR conflict is not merely the by-product of the struggle between U.S. imperialism and the Third World, any more than the reverse of this same simplistic proposition (as argued by Cold War ideologists of the West). Rather, whether or not we like to face the fact, there is an East-West Cold War which is quite real and which does impinge on the outcome of Third World revolutions at least as much as the other way around.

Tension and Accommodation

It is a truism that crises and confrontations frequently break out on the margins of empires, in situations of economic and social instability such as exist in Third World countries as opposed to the more stable states of Europe. This is where the power of one of the rival blocs tends to be destabilized or not consolidated.

The fact that we currently have a generalized Cold War rather than a hot one has depended, in part, on the ability of the rival imperialisms to reach successive relative accommodations in various parts of the world which then often become their respective consolidated spheres of influence.

Thus, the relative lack of confrontation in Europe today only came about after a great deal of friction in the late forties (e.g., the Berlin blockade, strenuous campaigning both for and against European rearmament, the Marshall Plan, etc.). In fact, as late as 1961, a great deal of tension still took place in connection with the erection of the Berlin Wall and related events in the two Germanies. These “accommodations” are by no means limited to Europe.

Thus, in 1962, after Kennedy blockaded Cuba, he and Khrushev agreed that the latter would withdraw the missiles he had previously installed in the island, and in exchange Kennedy pledged not to invade that country and to stop the numerous armed raids organized by right-wing exiles in Miami.

A byproduct of this agreement was that the U.S. government disarmed the bulk of the Cuban right-wing armies (while, of course, never giving up its imperialist economic blockade or its “right” to carry out small, selective “missions” against Castro).

This 1962 agreement is the origin of Cuba’s special Cold War status in the Western Hemisphere. Thus, it is no secret that the Soviet Union would have a qualitatively more hostile reaction to a U.S. invasion of Cuba than an invasion of Nicaragua.

Needless to add, none of these relative “accommodations” are cast in iron and permanently foolproof, not even the ones in Europe-they are ultimately dependent on the relation of forces between the two rival blocs. This is one reason why the danger of nuclear war is always with us.

Afghanistan

Following a line of analysis that sees Soviet imperialism as primarily defensive leads Davis to characterize the 1979 Russian invasion of Afghanistan as a “compensatory intervention . . . following NATO’s nuclear escalation in Europe.” (p. 27)

James Petras, for his part, also downplays the significance of the invasion of Afghanistan. Here is one of several instances where Davis’ and Petras’ arguments coincide. While insisting that the Third World is the central arena of today’s Cold War rather than Europe, they are selective in their analysis of the Third World: the crimes of U.S. imperialism are part and parcel of a geopolitical strategy, while Soviet invasions are “compensatory” or a sideshow.

Here again the blurred focus contributes to political ambiguity: while U.S. rhetoric over Afghanistan is legitimately condemned as a cover for its murderous activity in Central America, the slippery logic leads to dismissing Afghanistan itself as a minor issue.

In fact, if we are to view Afghanistan in a Cold War context, a strong case can be made that this invasion was more serious than the earlier Russian invasions of Hungary in 1956 and of Czechoslovakia in 1968. Whatever influence Russia (before and after the Russian Revolution) may have traditionally had in Afghanistan, the fact remains that this country, unlike Hungary and Czechoslovakia, had not been a part of the Soviet Bloc before 1979.

Whether an extension of the Soviet Bloc or not, the invasion of Afghanistan robbed the Afghan people of their right to self-determination. Neither Petras nor Davis specifically comment on this point. Nonetheless, given that so many on the left are willing to turn a blind eye to this fact, I want to emphasize here that even if the occupation of Afghanistan did not represent a significant escalation in the Cold War on Russia’s part, this has nothing to do with the obligation of the Left to condemn the invasion and support the Afghanis’ right to self-determination.

This right does not depend on the politics currently predominant among the rebels, any more than it did in the cases of the 1930s of supporting slave-holding Ethiopia against fascist Italy, or Chiang’s China against Imperial Japan.

This is a matter of principle, especially important to militants and revolutionaries in the Third World (e.g. members of the Black trade union movement in South Africa) who have not been receptive to the appeal of “really-existing socialism” such as the USSR and Cuba.

As socialists in the U.S., of course, it is our duty to denounce the U.S. imperialist demagogy concerning Afghanistan, while the task of Afghani revolutionary socialists is to fight the invaders, while opposing the reactionary social program of the predominant rebel leadership.

No Cold War in Europe?

Davis and Petras dismiss Europe as a significant arena of the Cold War. As Petras puts it bluntly in the opening statement of his article:

“The line of antagonism between the U.S. and the USSR does not run through Berlin, Warsaw and Prague but through the countryside of Guatemala, El Salvador, Angola, and Cambodia: and through the cities of South Africa, Brazil and the Philippines.”

Direct Russia-U.S. conflict as well as U.S. intervention have recently tended to take a sharper and more confrontational form in parts of the Third World, in fact sometimes become a hot war. But this trend has to be analytically integrated with, not separated from, the less confrontational but nonetheless real, conflict in Europe.

It is true that the U.S. has no intention of challenging Russia militarily in Europe. That is precisely what made the Cold War cold. But the U.S. and the Soviet Union have continued to challenge each other with other weapons-ideological, economic, and political.

The most recent example is the numerous and well-orchestrated attempts to line up the Polish workers’ movement with the Western side of the Cold War. Those, like Daniel Singer, who have been steadfast in their support for Polish Solidarity, while trying to combat these attempts, would perhaps not be so quick to dismiss the importance of Europe as a theatre of the Cold War.

All of us who share the view that the Cold War need not continue forever understand how important it is that the mass movements East and West, in Europe, the Third World and North America become conscious of their common interests and aspirations.

Sadly, such political integration is very fare from being realized. In fact, there is a powerful tendency for the oppressed in Eastern Europe to see the West as their friends, and for Central Americans to regard the Soviet Union in the same way. The possibility that the Cold War will lead to nuclear war in Europe has brought millions of Europeans to demonstrate against the installation of nuclear weapons in their continent, brought women to Greenham Common and the Spanish comrades to fight for the withdrawal of their country from NATO.

But while the threat of escalation may come immediately from tensions in the Third World, the political basis for alliance between the peace movements in the East and West lies in the common opposition to the same system of imperialist rivalries. It seems to me, therefore, that an approach which does not emphasize that there are two parties to the Cold War, each seeking hegemony in its own way, will make it more difficult to construct alliances and to break out of the notion that “the enemy of my enemy must be my friend.”

In this regard, I feel that E.P. Thompson has made an important contribution despite his mistaken “exterminism” analysis. I agree with Davis that Thompson sees exterminism as an autonomous dynamic of weaponry in East and West that while “deeply embedded in the existence of powerful isomorphic networks of interests [industrial, bureaucratic, military] …is not directly grounded in class structure nor is it coextensive with the reproduction or preservation of any mode of production.”

In my view, the single most disturbing aspect of Thompson’s approach to organizing against the arms race is a politics of panic that leads him to a rather extreme form of classless popular frontism. Surprisingly, Davis’ attack only vaguely hints at this crucial weakness.

Yet because Thompson does approach the Cold War as a symmetrical conflict between the U.S. and the USSR (although with an analysis different from that I have argued), he has played on the whole a progressive role in helping to build a European peace movement that is independent of all governments East and West. He has been supportive of the independent peace movements in Eastern Europe and has joined with them in their forthright opposition to all missiles and nuclear weapons whether they be placed in East or West Germany, Poland, or England.

Thompson has welcomed the joining of the causes of peace and freedom in Europe, if in a less consistent manner. While generally sympathetic to Polish Solidarity, he praised Jaruzelski’s “patriotism” at the time of the December, 1981 coup. However, Thompson’s continual dialogue with East European dissidents such as the Charter group in Czechoslovakia has helped to reduce the great suspicion with which the Western Left is held in progressive democratic oppositionist circles.

Thus, in spite of the serious flaws in his analysis, on this point I think Thompson’s approach has considerably more to offer than that of Davis and Petras.

What Is Symmetry?

In concluding his article, Petras says that while continuing to criticize Soviet institutions and foreign policy, the peace movement “must transcend the old boundaries of symmetrical responsibility for the arms race if it hopes to regain political credibility and initiative.” (p. 34)

In response, I would argue that the concept of “symmetrical responsibility” does not mean that the U.S. and Soviet empires are identical in their dynamic, which they are not, nor the same size (the U.S. empire is larger and more powerful). It does mean that they are both committed to dominance in their spheres and to enlarging them as opportunity arises.

It does not make sense to argue that one is “peaceful” while the other is “aggressive” since each is delighted to seek peace on its own terms, but willing to risk war if its power is threatened.

Nor does my view of the Cold War dpend on some minute-by-minute quantitative comparison of the brutality of the intervention of the two imperial powers–as if the Soviet Union were the biggest “bully of the week” when it invaded Afghanistan while the U.S. took that title when it bombed Libya. These are only the most brutal moments in an ongoing process of superpower rivalry and imperialist interventions.

The notion of the Soviet Union as somehow representing a peace camp–although a committed anti-Stalinist like James Petras would not use such terminology–creeps into his description of Gorbachev’s nuclear moratorium offer as “clear and positive proposals” which “should be endorsed by the peace movement in the West.” To answer this I will cite Jacqueline Allio and Ernest Mandel, authors who by no means share my theoretical perspective on the USSR:

“Nobody could consider that the proposals put forward by Gorbachev in Geneva represent a radical change in the USSR’s military policy. It is true that the Soviets are concerned to put a brake on the arms race and above all on Star Wars, which puts an intolerable strain on their country’s economy. But to conclude from that that the speeches of their leader of defence systems limitation represent anything more than diplomacy or that they could open up a new era in negotiations on arms control is going too far.

“The proof of this is that the oh-so-generous offer to reduce the nuclear arsenals was accompanied by a thinly veiled threat that if the United States did not put an end to Star Wars, it would be useless to think that there could be any limitation on production of strategic nuclear weapons. This is a long way away from the demands for unilateral nuclear disarmament put forward by the Western peace movements. The meeting of these demands would, however, be a step, however limited, in the direction of disarmament and peace. If Gorbachev had really gone along this road, this could have helped Western peace activists in their struggle to force their governments to take steps towards disarmament.” International Viewpoint, March 24, 1986, p. 20

In conclusion, I would like to emphasize that there is only one Cold War being fought in Europe and (more belligerently) in the Third World. In the conflict between two rival exploitative systems, neither one is our friend or ally.

Of course, in any given situation our side (i.e. the working class and its allies among the oppressed throughout the whole world) may well have to accept material or technical help from one or both of these rival systems, just like V.I. Lenin (and the Menshevik leader Martov!!) accepted the famous German transportation facilities to get back into Russia in the throes of revolution.

But it should be carefully noted that as a result of this important help, Lenin and the Bolsheviks did not give up one inch of their political perspective by, for example, arguing in their analyses and propaganda that the weaker German imperialism was somehow less obnoxious than the stronger Western kinds.

May-June 1986, ATC 3