Against the Current No. 228, January/February 2024

-

Election 2024 Deform & Dysfunction

— The Editors -

Door Opens to Return of Jim Crow

— Malik Miah -

History of the VRA: from Landmark to Dead Letter

— Maik Miah -

"Talking Socialism" on the Job

— Garrett Brown -

A Joint Israeli-U.S. Genocide

— David Finkel -

Weaponizing Antisemitism: The Battle at Indiana University

— Purnima Bose -

Abortion Rights Battle in Poland: Changes Not Forthcoming?

— Jacek Dalecki & Justyna Zając -

Policing Wildfires

— Ivan Drury Zarin -

Defeat of the Chilean Constitution

— Carolina Bank Muñoz -

Rustin, the Movie, the Organizer

— Joel Geier - About Rustin

- Boris Kargarlitsky Released!

- Labor on the Move

-

TDU's Rank-and-File Convention

— Michael J. Friedman -

Labor Calls for Ceasefire Now!

— Dianne Feeley -

UAW Faces the Tasks Ahead

— Dianne Feeley - Swedish Workers Strike Tesla

- Review Essay

-

Israel's West Bank Inferno & the Responsibility of Socialists

— Alan Wald - U.S. Politics Today

-

AOC's Journey to the Center of Politics

— Kim Moody -

Unprecedented Times, or Media Narrative

— Harvey J. Graff - Reviews

-

Torture and the Law

— Matthew Clark -

Fire Alarm -- It's Up to Us

— Michael McCallister

Joel Geier

BAYARD RUSTIN WAS the most talented mass organizer the American left has yet produced. His greatest success was the 1963 March on Washington, a turning point that aided the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 banning segregated public facilities and discrimination in employment.

For many years, Rustin’s accomplishments were minimized, hidden or denied because he was an openly gay man. Gay consciousness in recent years reestablished his importance to the civil rights movement, but beyond the LGBTQ community, he often remains an obscure, minor figure.

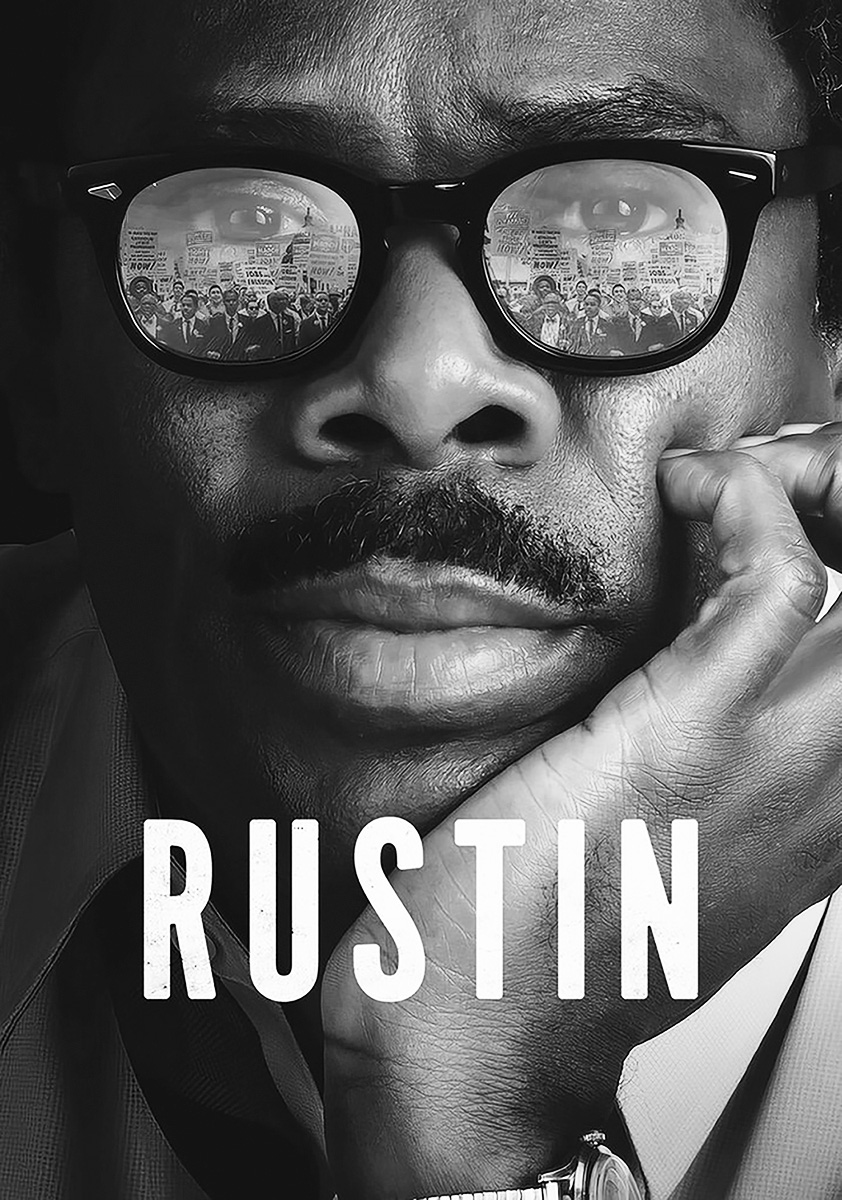

Rustin, the new movie celebrating the 60th anniversary of the March and staring Colman Domingo as Rustin, restores Bayard’s importance as the architect of the March.

It is a powerful movie that reawakens memories of American reality before the victories of the 1960s. With small snippets of Little Rock, the sit-ins and Birmingham, we are reminded that brutal white racism was tolerated as daily norms. It underscores how disgraceful are the current attacks to roll back the gains of the 1960s struggles when conditions were even worse than today’s reactionary political and racist climate.

It was only mass struggle from below that overcame those conditions. As the movie suggests, most of the political establishment of the day — the Kennedy Administration, the FBI, congressional Democrats from Adam Clayton Powell to Strom Thurmond — tried to prevent the March. The worst attempts to abort the March were heavily directed against Rustin, its organizer and public face, as a draft dodger, communist, homosexual, and convicted “sex pervert.”

The power of the movie is its excellent portrayal of how Rustin organized the 1963 March. It begins by dramatically counterposing his role in the March on Conventions of 1960 to the 1963 March.

In 1960 Rustin was driven out of leadership and organizing, while in 1963 the attacks against him were unsuccessful. The movie naively depicts both outcomes as dependent solely on personal decisions by Martin Luther King. In 1960, King is presented as intimidated by gay-baiting blackmail by Congressman Adam Clayton Powell in collaboration with Roy Wilkins, the head of the NAACP. But in 1963, King does not capitulate.

In presenting the changing dynamic between the two marches and Rustin’s role as a function of King’s individual personal choice, the movie fails to understand that the two different outcomes resulted from the change that the mass movement underwent in the intervening three years.

Through direct action struggles, the movement had become more militant while its political consciousness, combativity and self-confidence had matured. It was skeptical, even antagonistic, to establishment figures and had elevated King to a more powerful position than Democratic Party hacks like Powell or Wilkins.

Movement Strategist

The movie focuses on Rustin and King, but unfortunately does not explore the partnership they had developed in the 1950s, which turned each of them into essential instruments of the emerging new movement.

In the early days of the 1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott, the historic Black trade union leader A. Philip Randolph sent Bayard, his closest political collaborator, to Montgomery to determine what national support they could provide. Bayard had long, intense discussions with King, in which he convinced King of nonviolent resistance.

Bayard became convinced of King’s potential national role as a great, inspiring orator with a brilliant mind. King was then at the start of his career, unknown outside Montgomery, politically inexperienced and lacking many organizing skills. Bayard became his principal political adviser, organizer and fundraiser, and spent the next three years working to promote King as a national leader.

Rustin ghostwrote King’s first published article, “Our Struggle,” for the magazine Liberation, of which Bayard was an editor. It was the first of many King speeches and articles that Rustin drafted or edited, including “Stride Toward Freedom.”

The key idea that Bayard took from the bus boycott mobilizations and mass meetings was that the Black church had the potential to be the vehicle for setting in motion the Black working class and tenant farmers. The only independent Black institution in many places could not be ignored or bypassed.

Bayard proposed to King the creation of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) as an organization for those ministers who would engage in direct action. The formation of the SCLC as King’s organization elevated King as the central leader of the Black church, the channel for the southern mass movement.

In the North, Rustin became the spokesman for King, the SCLC and the southern movement. He created the ties between King and A. Philip Randolph. Randolph had been the organizer of the famous March on Washington Movement of 1941 that won the Fair Employment Practice during WW2, and of the threatened 1948 March that forced the end of segregation in the armed forces.

Rustin arranged the first event in support of Montgomery and King, a Madison Square Garden rally of 20,000 people. It was an enormous breakthrough in the 1950s climate of Cold War McCarthyism. Building on this success, Rustin became the coordinator of what was then called the Randolph-King wing of the civil rights movement, the direct action forces in competition with the court and legislative lobbying approach of the NAACP and Urban League who opposed mass actions.

The Randolph-King forces organized the only three mass demonstrations of the late 1950s, the Prayer Pilgrimage and two Youth Marches for Integrated Schools. These successful popular rallies, whose size ranged from 10,000 to 25,000 people, were the link between Montgomery and the 1960 sit-ins.

The Prayer Pilgrimage launched the SCLC and was King’s first platform in the North. His famous speech at the Pilgrimage, “Give Us the Ballot,” for the first time projected him as the up-and-coming leader, eclipsing both Randolph and Wilkins.

The Pilgrimage and Youth Marches could later be seen as dress rehearsals for the 1963 March, with identical setups. Randolph and King were the public sponsors, Rustin the organizer, the rank-and-file “Jimmy Higgins” work done primarily by members and allies of the Young Peoples Socialist League (YPSL). Any problems and kinks in these demonstrations became valuable instructions for the 1963 March.

Confronting the Democratic Party

It came as a confusing shock when King agreed to Bayard’s expulsion from organizing the 1960 Marches. In 1960 Rustin and his allies, now backed up by the newly formed Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), proposed to inject civil rights into the presidential elections through Marches on the Democratic Convention in Los Angeles and the Republican Convention in Chicago, with King and Rustin as co-directors.

The March on conventions demanded that the Party platforms back an end to Jim Crow public accommodations and support Black voter registration in the South, including protection for civil rights workers.

Rep. Adam Clayton Powell asserted that unless the March on the Democratic convention was called off, he would publicly charge Rustin with having a gay affair with Martin Luther King. King capitulated, and Rustin’s forced resignation was accepted.

While Rustin was sacrificed, the Marches went ahead (although the movie implies otherwise) and were highly successful. Michael Harrington substituted for Bayard as co-director with King. At King’s request, I became youth director for the Chicago March. The Los Angeles March had 5,000 people and Chicago 10,000, double what we had hoped.

Rustin, however, was kept out of civil rights activity for the next three years. He spent those years in antiwar work, much of it abroad. His main contact with the civil rights movement was in helping to mentor and educate SNCC activists, particularly at Howard University, where his protégé Tom Kahn was a SNCC leader. These were years of frustration, pariah status, of irrelevancy.

Rustin’s road back to leadership came through his conceiving of the March on Washington in conversations with Randolph. Their original idea was for a Centennial March to celebrate the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. Randolph and Rustin believed that the tragic betrayal of Reconstruction was its failure to provide economic independence for the freed slaves.

Randolph convinced Bayard to organize an Emancipation March to demand the unfilled economic promises of Reconstruction. As Rustin wrote in the draft proposal for the March on Washington there had been ”no fundamental government action to terminate the economic subordination of the American Negro…Integration…will be of limited extent and duration as long as fundamental economic inequality along racial lines persist.”

To solve that core problem, the Black struggle against racism, he wrote, should be the catalyst which mobilizes all workers for a program of economic justice. Randolph and Rustin aimed to create a labor and civil rights alliance, concretized as the March for Jobs and Freedom.

The March succeeded in assembling 250,000 people, primarily through the Black churches, NAACP branches, and the labor movement. It was one-quarter white, and was successful in mobilizing trade union support through Randolph’s organization, the Negro American Labor Council, and through liberal unions with large Black membership like District 65, 1199, the UAW and others.

George Meany and the AFL-CIO, however, refused to endorse it.

Rustin’s genius in organizing the March is the heart of the movie. His planning brilliance came from his political sophistication, strategic talent and vision, and from never losing track of the larger objectives.

His attention to every detail was legendary, as the movie depicts. His energy, enthusiasm and charisma were contagious. His sparkling oratory and unbelievable capacity for work inspired his staff of young recruits to devotion, commitment, self-sacrifice and incredible workloads. He encouraged them by example to give everything for the movement and its goals.

Some Still-Hidden History

In restoring the work of Rustin and in portraying the openly gay side of his life, Rustin breaks with traditions that have hidden both the existence of gays and their contributions from our history. Yet the film repeats those same traditions in writing out the work, ideas and contributions of socialists.

The movie never mentions that Rustin and his closest collaborators were socialists, and they influenced the movement with socialist ideas. Rustin was for many years the public spokesman and organizer of the A. J. Muste tendency of pacifist, Third Camp Socialists, radical opponents of capitalism and Stalinist class societies, and the imperialism of both Washington and Moscow.

In the 1950s the Muste group and Rustin had close working relations with the Shachtmanite (then the Independent Socialist League) tendency, particularly its activist youth group. The core of Rustin’s staff came from the YPSL. Tom (Kahn), Rachelle (Horowitz), Eleanor (Holmes) and Norman (Hill), named in the film, as well as other young socialists, were a part of the Rustin operation for years; all had worked on the Youth Marches.

New recruits from SNCC and Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) were also members or allies of the YPSL. One of Bayard’s strengths was that his devoted staff were talented, politically sophisticated leaders, who had been educated as cadres in the socialist movement. They did the grunt work — getting the endorsements, mobilizing people, organizing the car pools and buses — making all of Bayard’s details a reality.

They agreed with Bayard politically, so collaboration led to merger, with Bayard becoming the leading spokesman of the Shachtmanite current in the civil rights movement. None of this history is ever mentioned in the movie.

Moving Right

By the time of the 1963 March, Rustin and many Shachtmanites were tragically being drawn into Democratic Party politics. The year after the March, they and Bayard accepted the Democratic Party “compromise” that sold out the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party at the 1964 convention. Justification followed in Rustin’s famous article embracing coalition politics “From Protest to Politics.”

Worse, Democratic Party politics were to lead Rustin and the Shachtmanites into coalition with the Johnson Administration during the Vietnam War. They went from being a left wing of the civil rights movement to its right wing, and Bayard eventually became the chairman of the right wing Social Democrats USA.

Those of us who had been part of the Rustin civil rights operation, and who continued the revolutionary socialist politics we had once shared with Rustin and the Shachtmanites, had to start over again as a small group in 1964, as the Independent Socialist Club, later called the International Socialists. But that is all beyond where this biographical movie ends.

January-February 2024, ATC 228

I was a fulltime volunteer on the staff of the March on Washington in 1963 and a YPSL.