Against the Current No. 17, November/December 1988

-

Paralysis and Change in Eastern Europe

— The Editors -

Bernie Sanders: Campaign for Congress

— David Finkel -

A Year of the Palestinian Uprising

— Edward C. Corrigan - Phtographers and the Israeli Army

-

Activists Discuss Antiracist Unity

— Andy Pollack - Afghanistan, the War and the Future

-

Introduction to Afghanistan, the War and the Future

— The Editors -

Afghanistan at the Crossroads

— Val Moghadam -

A Failed Revolution from Above

— R.F. Kampfer - Mexico in Crisis

-

Introduction to Mexican Elections and the Left

— The Editors -

Toward a Unified Left Perspective

— Arturo Auguiano - Opposition Political Parties in Mexico, 1988

-

For a Revolutionary Alternative

— Manuel Aguilar Mora - Music for the Movements

- Music for the Movements: Two Interviews

-

Billy Bragg: Alive and Dubious

— Peter Thomson interviewing Bill Bragg -

"A Simple Squatter from NYC..."

— Peter Thomson interviewing Michelle Shocked - Dialogue

-

Revolutionaries in the 1950s

— Samuel Farber -

Life in a Vanguard Party

— Stan Weir -

Another View of W.J. Wilson

— Washington-Baltimore ATC Study Group -

Big Red Fred: 1927-1988

— Theodore Edwards - Reviews

-

Whose Team Are You On?

— Marian Swerdlow -

Poetry, Politics -- and Passion

— Patrick M. Quinn -

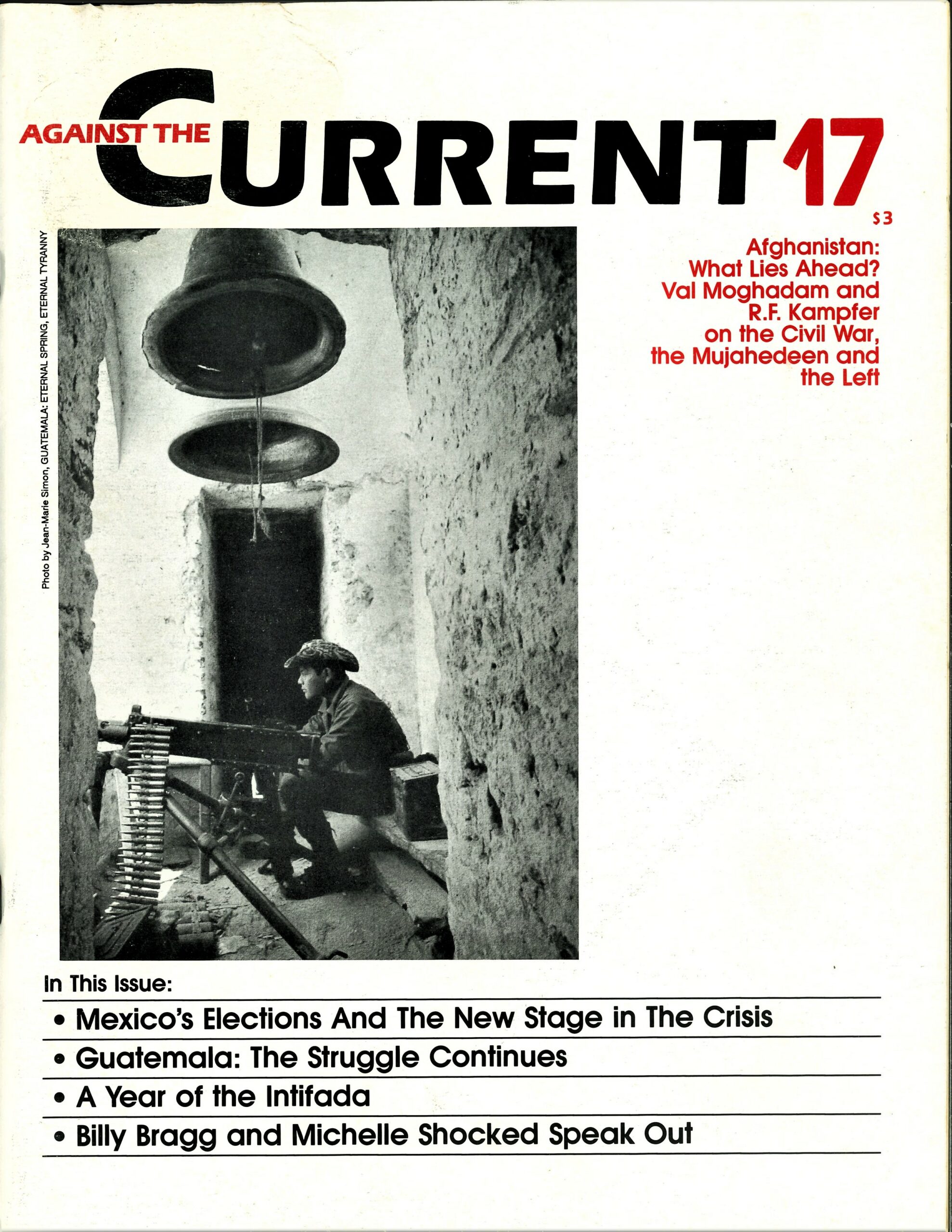

Guatemala in Midpassage

— Jane Slaughter

The Editors

IN EASTERN EUROPE, everything changes and yet some things never change. The recent strike wave in Poland, the second in 1988 alone, illustrates this paradox. Solidarnosc, the greatest trade union in history as well as a social movement of over ten million Poles, had been proclaimed dead and buried long ago by General Jaruzelski, not to mention many sophisticated intellectuals of the western left.

Yet in the summer of 1988, as it had eight years earlier, the Polish working class flexed its muscles for the restoration of its own union. Once again, the strikes began with the shipyards and steel works, then spread to the southern coal mines where-once the struggle was unleashed-determination, toughness and militancy are greatest While the first strikes of 1988 saw economic demands in the most prominent place, the second wave centered on the relegalization of the banned independent union.

By all accounts, the summer strike wave incorporated a young, post-1980 generation of workers in the struggle – a generation disgusted by the failure of bureaucratic economic “reforms” but not intimidated by the mass internments and violent repression of martial law. These young militants gave Lech Walesa, the leader and strike spokesperson of the Solidarnosc movement, a rough ride when he pleaded, successfully, for the strikes to end, given the government’s promises to negotiate Solidarnosc’s return to legal status.

And what then? No sooner had the strikes ended than the Polish Communist bureaucracy demonstrated, exactly as it had done in every crisis from August 1980 until martial law in December 1981, that its concessions to the workers’ movement and to “society” are purely tactical. Even after the government resigned en masse in September, the regime’s spokespersons have decreed that there will be no legalization of Solidarnosc, only the “right” of its members to join the official unions of the party-state. There is no more reason to expect that Polish workers will accept this ersatz unionism than to think that the bureaucracy has any chance to solve Poland’s terrifying economic, ecological and social crises.

Indeed, the failure to accept workers’ rights or eve conduct meaningful discussions with authentic workers’ representatives, and the inability to carry out any reform policy that might deflect dissent, are closely linked. There is nothing new in this. It is evident by now that despite its advanced state of decomposition, the Communist party in Poland has no real policy other than to hold on to power through refined techniques of political manipulation, a protracted war of economic-psychological exhaustion against the population, and military repression. In the Polish context, at least, the promises of the party “reformers” and “liberals” have been exposed as empty babble, to be taken seriously only by those left intellectuals in the West who dislike Stalinist excesses but fear the workers more.

What is new is that both the regime and the workers’ opposition in Poland may be weaker than in 1980-81. The regime has lost its political trump card, the threat of Soviet military intervention that it used to warn society against “going too far.” With Gorbachev’s ascendance, the Soviet defeat in Afghanistan and the new climate of international detente, any prospect of Soviet tanks rolling in Poland is too remote to have an intimidating effect. At the same time, it is evident that the opposition has undergone deep and complex divisions over perspective that has penetrated deep into Solidarnosc and the working-class population.

Should the population and the independent union movement seek a framework for cooperation with the government, accepting that this would entail “market” reforms in a context that would impose sacrifices on the working class? This now seems to be a perspective argued by Jacek Kuron, a long-time Solidarnosc adviser and a crucial figure in the years of semi-clandestine organizing for independent unions.

Kuron’s argument seems to be that the economic logic that compels sacrifice is overwhelming. Yet it would seem equally unavoidable that such a course would require power away from the workers at the shop-floor level and the conversion of Solidarnosc into the all-too-familiar structure of concessions bargaining, bureaucratic collaboration and “Team Concept” well known to U.S. auto workers.

Nothing perhaps captures the new moment in Poland, and the dangers confronting the movement, so much as the only the Rakowski regime’s stunning announcement of the closure of the Gdansk shipyard. This vicious exercise in Thatcherite Communism combines punitive political action against the workers who gave birth to Solidarnosc with the application of “market” criteria of profitability to shut down enterprises in an economic downturn. The Polish bureaucracy, no longer able to use Soviet tanks as its blackmail of last resort, now expresses its open admiration for the “toughness” of Britain’s Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in restructuring British capital at workers’ expense.

The defense of the Gdansk shipyard is in a very real sense the defense of Solidarnosc’s existence. There could be no better symbol to organize a new mass resistance. But acceptance of “market” logic could literally paralyze the movement. If workers have been convinced that only the “market” can save the country, they will have no answer to the fatalist argument that strikes or factory occupations to save the “failing” shipyard are futile and backward. Solidarnosc faces the prospect of being drawn into joint participation-which for once, Communist authorities would all too happily welcome — in selecting the victims of restructuring.

Such is likely to be the fatal outcome if the Polish working class accepts the disastrous choice between bureaucratic state ownership versus the market-if it is unable to wage a struggle for genuine social ownership, of democratic collective control of the entire economy through its own mass institutions.

In the present interval, when the Solidarity movement is too strong to be suppressed but not yet capable of imposing its existence, much will depend on whether the union structures weakened by the years of illegality are rebuilt at the workplace level In the process, Polish workers will have to consciously decide whether their next gamble — for any course of action is indeed a gamble — will be based on seeking cooperation or confrontation with the regime. In any case, given the bureaucracy’s proven record of deceit, all that is reasonably certain is that a third round and perhaps an explosion is coming.

On one point, however, there cannot be a compromise: the Polish workers’ movement Solidarnosc must continue to command the unconditional support of all those for whom “socialism” means working-class power rather than some supposedly benevolent or progressive tutelage over the workers. (We do not, of course, mean to imply that there has been anything benevolent or progressive about Communist Party rule in the past four decades in Poland.)

Whatever its inner differences in perspective, or whatever mistaken illusions it may hold regarding the “democratic “values of western imperialism or about “sharing the burden of sacrifice” with the bureaucracy, Solidarnosc was and remains the vanguard of the fight for workers’ rights in Eastern Europe and of all those forces that stand for a glasnost-from-below.

It is to those forces, including the independent socialist clubs of the Soviet Union, along with the independent peace movements of Hungary and East Germany as well as the U.S.S.R, that socialists look for the critical analysis that becomes a mass force in the context of a social upsurge. These forces have not lost sight of what they owe to the continuing fight of the Polish working class-and neither will we.

Elsewhere in Eastern Europe, the dialectic of new struggles and old is taking even more explosive, and often messier, forms than in Poland. If the abject failure of economic reform in Poland has propelled the fight for genuine trade unionism back to center stage, economic failure in Yugoslavia has spectacularly revived national struggles and antagonisms.

A forthcoming issue of Against the Current will present an analysis of the diverse and sometimes contradictory aspects of the present Yugoslav crisis: authentic mass mobilizations for political democracy, demands for redress of economic grievances and chauvinistic hostility among the nationalities.

November-December 1988, ATC 17