Against the Current No. 235, March/April 2025

-

Genocide and Beyond

— The Editors -

#StopFuelingGenocide: Boycott Chevron!

— Ted Franklin -

Capitalism Is the Disaster

— Peter Solenberger -

A Fight for Our Unions

— Anna Hackman - Patrick Quinn, presente!

- The Palestine Wars on Campus

- Women in Struggle

-

India: Mass Struggle vs. Rape Culture

— Jhelum Roy - The Gaza Genocide: Women's Lives in the Crosshairs

-

Betrayed by the System in Brazil

— L.M. Bonato -

Autonomous for Abortion Care

— Jex Blackmore -

Remembering Barbara Dane

— Nina Silber - Review Essay on Communist Women Writers

-

Communist Women Writers: The Emergence of Memory Culture

— Alan Wald - Review Essay on the USSR's Fate

-

A Revolution's Fateful Passages

— Steve Downs -

Martov and the October Revolution

— Steve Downs - Reviews

-

A Genocide in Its Context

— Bill V. Mullen -

The Zionist Lobby: A Chronicle

— Don Greenspon -

Oil Dollars at Work

— Dianne Feeley -

All Eyes on Palestine!

— Frann Michel -

A People's History, Retold in Graphics

— Hank Kennedy

Anna Hackman

IN THE MIDDLE of a global pandemic, Black youth across the country were at the forefront of one of the largest uprisings in modern U.S. history. It spanned all 50 states and over 20 different countries. The uprisings are a powerful reminder of what working-class people can do with political clarity and solidarity from below.

In Seattle, where we are based, the 2020 uprisings — led by Black youth in the Movement for Black Lives — erupted at a time when we were fighting for the soul of our union. The movement’s clear demands and organized, direct action opened a door for rank-and-file workers to organize in solidarity with the movement, and with each other.

I am a Black, queer labor and community organizer, and an educator at a local community college. In the spring of 2020, along with teaching virtually during the quarantine, I worked with a small group of colleagues to make important shifts in our union. As contract negotiations approached, and our working conditions radically shifted, we became increasingly frustrated with the bureaucratic structures of our union.

Major decisions about our contract were made through closed negotiations and backroom deals. Aside from the occasional, performative membership meeting, or a short survey, there was no real input from the rank and file. We were tired of the secrecy, the lack of democratic procedures, and the lack of rank-and-file power in the union. We began organizing.

One of the most important, grounding principles of our organizing was a commitment to organizing as rank-and-file workers. First, the issues we encountered with our union were part of a larger problem in the labor movement. Many unions had the same, inaccessible bureaucracies that ground service industry unionism. Second, rank-and-file workers have leeway that labor “leaders” cannot do on their own. It is easier for us to take bold, direct action. Finally, and more importantly, we wanted to redefine what union power meant.

In the eyes of high-ranking union officials, we were nobodies. We had no special title, no special status, and therefore had nothing to offer but our dues. We understood that in order to win the contract we deserved, and improve our working conditions in the long-term, we needed to build power from below. Being a nobody was our strength. When the rank and file is strong, the union is strong.

SPOGOut!: Seattle’s Rank-and-File Answer

the Call for Solidarity

As we organized our colleagues, George Floyd was murdered by police in Minneapolis. In Seattle, the uprisings that followed were just a block away from our college, where the Capitol Hill Occupied Protest Zone (CHOP) was formed. Many of the youth being brutalized by police were our students. We followed the movement closely and looked for openings to organize rank-and-file faculty to support the struggle. That opening came in the call for the Martin Luther King, Jr. County Labor Council (MLKCLC) to expel the Seattle Police Officer’s Guild (SPOG).

Everything we accomplished that year was because of Seattle’s Black youth and the formation of CHOP. Their political vision and organization opened doors for everyone to envision our collective liberation. In June of 2020, in response to the murder of George Floyd and violent repression against protestors by Seattle police days earlier, hundreds of people demonstrated in the streets of Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood. Demonstrators returned, day after day, in the face of police violence, with a vision of a world without police. It was a powerful and inspiring display of working-class solidarity.

CHOP formed after Carmen Best, Chief of the Seattle Police Department, shut down the 12th precinct. One of the calls of the Movement for Black Lives was to reimagine what safety and security can mean. It did not have to mean policing and surveillance. “Safety and security” could mean collective care, a world where people had their basic needs met, a world where they could live free from state-sanctioned violence.

CHOP, which spanned several blocks of the Capitol neighborhood, was a literal imagining of this world. Anyone who entered its gates would find free food, celebration, art, a community garden, and consciousness raising spaces. It was a powerful site to celebrate struggle. As community college faculty, we wanted to make visible the links between our exploitation and police violence to our colleagues.

We went into quarantine in March of 2020. At our college, we had to shift all of our courses online. With minimal time to prepare, and minimal support from the college, we had to rapidly transition our courses. The pandemic both revealed and intensified our working conditions. We wanted to politicize the pandemic, our working conditions, and tie them to the Movement for Black Lives. And it was important for us to do so as rank-and-file workers.

We wrote a position paper, outlining the links between the pandemic and our working conditions, which we asked our colleagues to sign in support. This gave us an organizing foundation to mobilize colleagues to articulate the connection between our working conditions and mass incarceration when the uprising began months later.

Our paper was a call for our colleagues to organize as rank-and-file workers, and to stand in solidarity with social movements. In the following years, we organized teach-ins and rallies to mobilize our colleagues towards open negotiations and a member-led union.

The harmful patterns we encountered in our union were also present in the MLKCLC. The MLKCLC is a centralized body of labor organizations based in King County, Washington. The labor council formed in 1888 as a coalition of labor organizations committed to building worker power. Over 100 years later, the council had fallen into the same pitfalls of service industry unionism that we found in our unions. While each union had delegates, many of us did not know who our delegates were (some union members weren’t aware of the labor council at all).

Moreover, the labor council had a reputation for bureaucratic, convoluted decision-making procedures that were difficult to navigate. In their inaccessibility, the MLKCLC sent a similar message as our union: if you didn’t have a special position in the labor council, you had nothing. You were nobody. As a result, the labor council often made decisions that went against working-class interests.

In 2014, for example, the MLKCLC admitted the Seattle Police Officers’ Guild (SPOG) into its ranks. In the middle of a mass movement against police violence, the labor council helped SPOG implement vague accountability processes that undermined the movement’s demands. To allow SPOG into the labor council was a slap in the face to the working-class organizers who were beaten and killed at their hands. They should never have been allowed into the MLKCLC, and they certainly should never have had so much support from labor in their contract negotiations.

Well before the quarantine, the Highline Education Association (HEA) put forward a proposal to expel SPOG from the labor council. The vote was tabled. The 2020 uprisings provided an opportunity to reintroduce SPOG’s expulsion and HEA issued a call for all unions to support the vote to expel.

We went to meetings with small groups of labor council delegates who supported the vote to expel. What we saw was a lot of backroom dealing and confusing, heavily bureaucratic procedures. Since we were not delegates, was no space for us and our work. We were nobodies. We had no say.

Around this time at CHOP, I ran into a comrade active in the Seattle Education Association (SEA), who wanted to support the effort to expel SPOG. They were also struggling to understand the bureaucratic procedures of the labor council. We were frustrated that a labor body that was supposed to represent our interests was so closed off to us. It was part of a larger pattern of undemocratic decision-making in labor.

We decided that we could put pressure on that decision by organizing a rally on the evening of the vote, and hold it in CHOP. The Movement for Black Lives opened this door for us, and holding the action in CHOP was an important show of solidarity for the demand to defund the Seattle Police Department.

We put out a call to all union workers to speak out against racist police violence and call on the labor council to expel the police. There would be no more secrecy. If the MLKCLC did not vote to expel SPOG, they would do it in front of the rank and file.

We scheduled a planning meeting at CHOP less than 72 hours before the MLKCLC vote. The turnout exceeded our expectations and we agreed to hold the rally. We organized an outreach plan, a strong list of speakers, and got to work.

Despite very little time and no money, we worked nonstop for three days to mobilize workers, fundraise, and set up a professional sound stage in Cal Anderson Park. Over 600 people came to hear educators, construction workers, and performers make the links between our exploitation and a violent, racist police force.

Many labor council delegates attended in a show of solidarity. They told us that some members of the labor council’s executive board had expressed concerns about our rally. They knew the rank and file was watching.

At around 9pm, we danced and cheered in Cal Anderson Park — the heart of CHOP — as the MLKCLC, in a 55 to 45 decision, voted to expel the Seattle Police Officer’s Guild from its ranks. This was a historic victory and a powerful show of rank-and-file solidarity.

We didn’t have formal positions or any institutional power. What we did have was clear politics that were antiracist, feminist, anticapitalist, and grounded in solidarity. And with that, we created a collective push from below that helped make history. Our fundraising also exceeded our expectations and we donated the leftover money to Decriminalize Seattle.

Rank-and-File Power from Below:

The Labor for Black Lives Collective

The SPOGOut rally brought rank-and-file workers together in solidarity with the Movement for Black Lives. It was a demonstration of solidarity from labor that went beyond the typical, benign rally organized by labor “leaders.” It also brought workers together that, otherwise, would not often cross paths. We were educators, electricians, carpenters, longshore workers, grocery workers, and healthcare workers. We showed up in the ways that movement really needed us, and we did it with no real political power beyond our commitment to rank-and-file solidarity. We had to continue this momentum.

We continued to meet as rank-and-file union members. We would gather and talk about the need to democratize our unions and to build an antiracist, feminist, queer, and anticapitalist labor movement. We formed a labor contingent and showed up at the actions that followed the SPOGOut! Rally. Many organizers in the movement heard about our victory, and we were invited to speak at rallies and panels.

We wanted a way to demonstrate our solidarity in rank-and-file politics. One of my colleagues had the idea of developing a banner with the slogan “Labor for Black Lives.” They and their partner designed it, and had it printed at a local, Black-owned print shop. We brought this banner to every action we attended. Very quickly, community members called us “Labor for Black Lives.”

We decided to run with it, calling ourselves the Labor for Black Lives Collective. The name came from the community; it was a sign that our presence as labor was important. We released a short statement in support of local demands to defund the Seattle Police Department, and committed to supporting both the Movement for Black Lives, but also each other.

The formation of the Labor for Black Lives Collective allowed us to establish important links between labor exploitation and abolition. We organized teach-ins on police abolition with a labor lens. We also used nonhierarchical, democratic decision-making processes that were more aligned with the politics of local community organizers. In practice we wanted to challenge the top-down structures of our unions.

One of our first major actions as a collective was in support of a local abolitionist organization, supporting a group of formerly incarcerated workers at the Bishop Lewis work release site in Seattle. The site retaliated against workers for whistleblowing about a COVID-19 outbreak in the facility.

Originally the organization asked the labor council to take this matter on as a labor issue. Members of the labor council’s executive board gave them the runaround, sending them to person after person with no guidance. Frustrated and confused, they reached out to us to help them navigate the process.

We drafted a proposal and mobilized members of the collective to push their union delegates to get the labor council to sign onto a letter to the governor. The labor council approved the resolution and released a public statement recognizing COVID-19 in DOC facilities as a labor issue.

The abolitionist organizers we worked with later told us that they were able to leverage the labor council’s statement in a future action. The Bishop Lewis solidarity action reaffirmed our commitment to nonhierarchical, democratic structures. Organized as rank-and-file workers, we were difficult to contain. Even working within the labor council structure in this case — as nobodies within the council bureaucracy — we demonstrated collective power from below.

It was important to us that local abolitionist organizers reached out to us directly. It signaled that our work was having an impact and spoke to the need to democratize our unions and labor council. We continued to organize rank-and-file workers in support of the movement. We organized a labor contingent to go door knocking for Nikkita Oliver’s — an abolitionist organizer, attorney, and key leader in the Movement for Black Lives — primary campaign for City Council. While we had some political questions around electoral politics, we decided it was important to show up in the ways that the movement needed us.

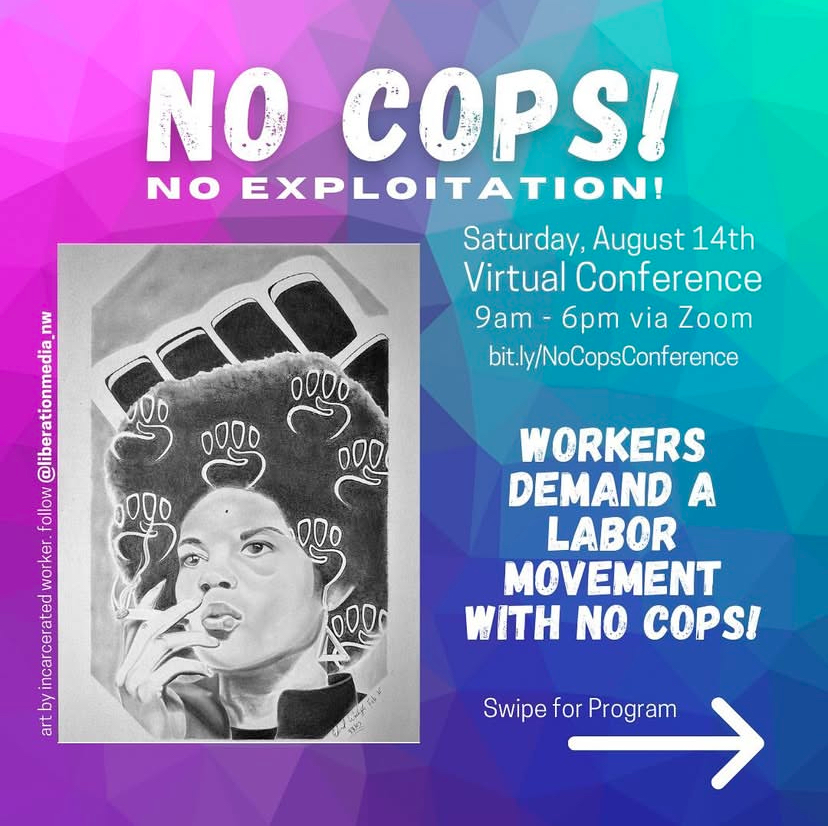

We continued to form relationships with other groups that had a labor and abolitionist focus. In August of 2021, we worked with other labor organizations to host a national, virtual abolitionist labor conference. Labor for Black Lives, SEIU Drop the Cops, Cop-Free AFSCME, IATSE Members for Racial Justice, and others, put together a day-long series of workshops linking the issues of mass incarceration, policing, racism and exploitation in our workplaces. Our opening keynote speakers were two currently incarcerated workers at a Washington State prison. They opened the conference with stories of their own exploitation inside, and a call to labor to join the movement to abolish prisons.

One of our greates successes is what Collective members have been able to accomplish in our unions. My local, after years of rank-and-file organizing, is currently in our first open negotiations process. Many of our members are also members of Seattle Education Association (SEA). With the rank-and-file politics and organizing skills they developed in Labor for Black Lives, they were key to organizing the Seattle teachers’ strikes in September 2022. As we all started to focus on our union work, the Labor for Black Lives Collective became inactive. But in our three years as a collective, we showed what rank-and-file workers can accomplish together.

Lessons Learned

We are in another important political moment with the re-election of Donald Trump. He has wasted no time in sending this country straight into fascism. The working class must be vigilant and organized. The formation of the Labor for Black Lives Collective taught us the necessity of a vibrant labor movement that stands in solidarity with social movements.

A vibrant labor movement is a democratic labor movement. Our organizing created spaces where you don’t have to be “somebody” to be part of the union. You just had to be a dues-paying member. Our work empowered others to join the work with us. And as rank-and-file members became stronger, so did our union. Labor will need to be organized in the upcoming years. The longstanding traditions of top-down, undemocratic bureaucracy will not move us forward. A strong rank and file will.

The U.S. labor movement has a long history of being closed off to BIPOC, women, and LGBTQ workers. They have reproduced the very systems that Trump leveraged for a second term in office. We must stand in solidarity with undocumented, BIPOC, and transgender workers, and everyone else Trump will target in the next four years. Labor cannot do this until we confront these issues at home. We need an antiracist, feminist, queer, and socialist labor movement led by the rank and file.

Labor for Black Lives was able to make an impact because we worked in coalition with each other. We worked in very different industries and trades, but our experiences of exploitation were similar we understood that the forces exploiting our labor were the same ones killing us in the streets.

Labor can have an impact in the upcoming years, but we cannot do it alone. We need to be in solidarity with our communities.

Most of all, labor needs to commit to organizing from below. Throughout our organizing, labor leaders constantly reminded us of our “place.” We didn’t know the rules like they did. We had no formal position or special status. We had no special connections. There was no real place for us in the labor movement. We were political nobodies and without their leadership, we were nothing.

It was true that we did not have the material resources that a top-down, service industry unionism values. But we had what mattered. We had clear, consistent politics. We had a commitment to organizing from below. We agreed that in a top-down union structure, we were political nobodies; we embraced that wholeheartedly. We understood that a union is nothing without a strong rank and file.

As I think about the upcoming years, this is what I am reminded of. As the Democrats scrambled to find that single leader to “save” us from Trump, our work in 2020 is an important reminder that we have the capacity to save ourselves. To organize as political nobodies, collectively from below, will be our strength.

March-April 2025, ATC 235