Against the Current No. 227, November/December 2023

-

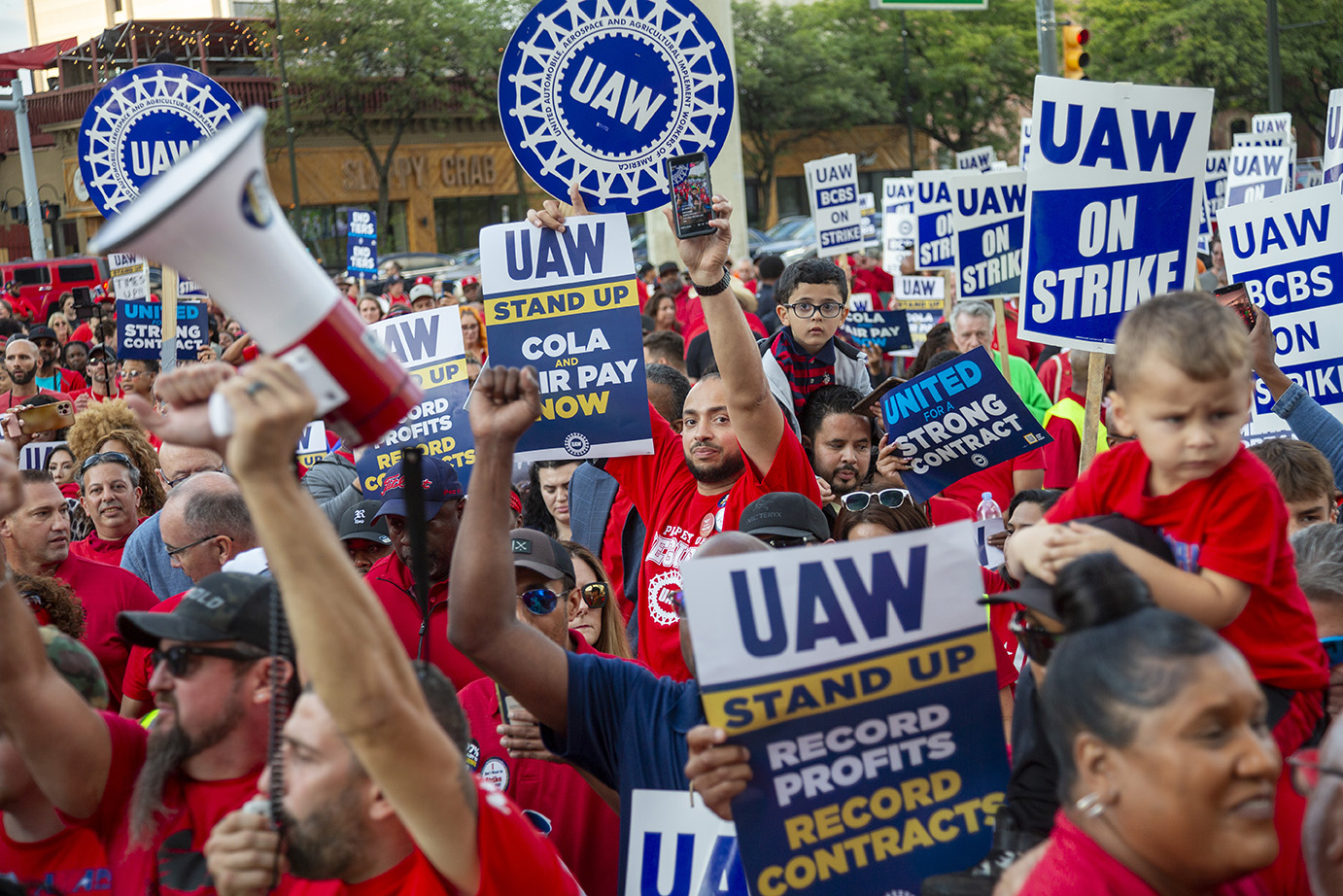

Auto: The Future on the Line

— The Editors -

Catastrophe in Palestine and Israel: Apartheid on the Road to Genocide

— David Finkel - Stand with Palestinian Workers

-

Parallel Fights Against Privatization

— Steve Early & Suzanne Gordon - Guatemala: Coup Instead of an Inauguration?

- New Labor

-

Strategies for Union Victories

— Dianne Feeley -

Writers Guild of America Wins

— Barry Eidlin interviews Alex O'Keefe & Howard A. Rodman - The Struggle for Self-Determination

-

Consistent Anti-Imperialism

— Solidarity -

Ukrainian Letter of Solidarity with Palestine

— Commons -- Ukraine -

On Imperialism Today

— Howie Hawkins -

In Solidarity with People's Struggles

— Fourth International -

Paths for Socialist Internationalism

— Promise Li - Reviews

-

The Testing of America: Birmingham 1963

— Malik Miah -

Echoes of Revolution

— Marc Becker -

The Making of Capitalism

— Mike McCallister -

Toward a "Transsexualized Marxism"

— M. Colleen McDaniel -

A Primer on Abolition

— Kristian Williams

Dianne Feeley

OVER THE PAST year several unions have adopted innovative and militant strategies as they go into bargaining with their employers. Key has been organizing campaigns to build membership participation. Central key element has been to publicize corporate profitability. Providing this information includes tracing where the profit was invested — or more likely, misspent. This has reinforced worker confidence in the need to take action.

At United Parcel Service (UPS), the Teamsters represent 340,000 workers under the largest private sector labor contract. Winning the 2020 election with a reform slate for top officers, the Teamsters launched a campaign to take on the successful corporation.

In fact, the reason the coalition of reformers won was dissatisfaction with concessions that the James Hoffa leadership had imposed through an arcane constitutional rule.

Along with disgust over the previous leadership, members realized how profitable UPS became during the pandemic as workers kept the economy humming. Yet workers had endangered their lives and those of their families. Teamsters were also pushed to the breaking point as they worked forced overtime while UPS accumulated enormous profits. In the eight years before the pandemic, UPS’s yearly profit ranged from $7.1 to $8.2 billion. Then in 2021 UPS profits soared to $13.1 billion, reaching $13.9 billion the following year.

Yet for the 2023 contract UPS wanted the flexibility to introduce a seven-day schedule, build in more surveillance over workers and continue use of contract workers.

Ready to Strike

The old contract ended midnight July 31, 2023. Launching kickoff rallies the year before, the union surveyed its members to nail down core demands. That was followed by a campaign to sign pledge cards committed to striking if that became necessary.

This work involved union staff but more importantly activated the union ranks. The participation of the longtime Teamsters for a Democratic Union was essential in encouraging members to become activists.

By spring, the Teamsters were holding webinars, launching trainings to map out workplaces, holding parking lot rallies, and developing concrete plans for making sure everyone was “strike ready.” They developed a UPS Teamsters app so members could follow negotiations.

Part of the preparation compared CEO Carol Tomé earning $27.6 million while UPS part-timers were making as little as $15.50 an hour. Since UPS drivers are much better paid than loaders, it was important to expose the reality of that spread.

Usually negotiators don’t reveal what is taking place at the bargaining table but only detail the gains in the tentative agreement (TA) at the end of the process. But President Sean O’Brien announced agreements as UPS signed off on each issue. This meant the membership was able to keep track.

Members felt breaking with the blackout around negotiations was liberating. It became increasingly clear they were winning significant gains — gains some of the old guard had declared impossible to win.

One Teamster driver I spoke with was afraid that the negotiating team would prioritize wage increases over demands around better working conditions. Given the relative transparency, he could see his fear was misplaced.

When contract negotiations broke down three weeks before the strike deadline, the union encouraged “practice picketing” before or after work. These actions showed the corporation that the Teamster ranks were well prepared to strike.

Bloomberg predicted a strike could cost UPS $170 million a day as well as a probable loss in market share. Faced with that reality, UPS came back to the table and quickly put forword a proposal and signed off on the agreement.

While some members and labor analysts think the Teamsters could have won more by striking, nearly half the membership turned out to vote, and 86.3% voted yes.

What is needed now is to make sure the contract gains are enforced as militantly as the contract campaign. Hopefully members will remain innovative and aggressive here too. (See Kim Moody and Barry Eidlin’s articles in ATC 226 for their analyses.)

Learning from the Teamsters

With the UAW contract expiring six weeks after the Teamster-UPS one, the newly elected reform UAW officers viewed the Teamsters contract campaign as a model.

The enormously profitable corporations were happy with being able to keep temporary workers (called “supplementals” at Stellantis) as temps, to be made permanent or fired at their discretion. They were also interested in maintaining a two-tier structure. This guaranteed that when temps became permanent and began an eight-year progression to the top wage scale, they never acquired benefits equal to those hired before 2007. The Detroit Three were willing to offer what they considered a reasonable wage hike, around 9-10%.

The reform officers needed to demonstrate their determination to carry out their campaign slogan, “No concessions, no corruption, no tiers.” Implementing that slogan could only be accomplished by activating a membership who had been instructed to “leave the work to the leadership.”

Winning office in the aftermath of a dozen high-ranking UAW officials admitted to stealing two million dollars of the members’ dues money and imprisoned, they had to figure out how to activate a membership disgusted by corruption and told for years it should accept concessions to keep the plants open.

The new leadership knew they had to win workers’ trust. They began by gathering names and inviting members to attend YouTube/Facebook Live weekly updates. Each week a text or email went out; each week the number of autoworkers watching the video grew.

During the first few programs UAW President Shawn Fain focused on of the Detroit Three’s profitability. Between 2013 and 2022 they’d made a quarter trillion dollars in profits, paid top management handsomely, plowed the money back into stock buybacks and closed 65 plants.

Fain maintained that if CEOs had a 40% increase in their salaries, workers deserved no less. The battle was between working people and the billionaire class.

Typically, the opening round of negotiation starts when the UAW president shakes hands with the Detroit Three’s CEOs. Fain announced that since the demands being put on the table were from the membership, he’d shake hands with members. Only when there was a fair contract would he have some reason to shake hands with CEOs.

As negotiations opened, Fain and his team went to a Ford, GM and Stellantis plant in the Detroit area. He greeted members as they were coming in or leaving work. He shook their hands and his team signed them up for updates. Whether or not the leadership of the local was on board or not, the members had access to information.

This event signaled to the membership and the larger public that the negotiations were going to be conducted differently. How could be that interest be channeled?

Reversing Concessions, Building Solidarity

While taking on corporate greed remained a theme, the focus of the weekly meetings began to shift to a discussion of the 10 demands. The majority were to restore what workers had previously won, then lost in the 2009 economic recession.

Cost-of-living adjustments (COLA) had been suspended. Since most of the COLA money won during a given contract was then folded into the base wage in the following one, this loss has suppressed wages ever since.

Another important concession allowed the Detroit Three to retain newly hired workers as temporaries rather than moving to permanent status after 90 working days.

Even once made permanent, workers hired after 2007 earned a lesser wage with few benefits. At first the lower-tiered worker had an inferior health care package along with no post-retirement health care or pension.

Over the years, UAW members always raised demands to get rid of the abuse of temporary workers and end the system of tiered wages and benefits. Some adjustments have been made in subsequent contracts, but the tiers remained, or even metastasized, much to the dismay of the membership.

Another demand called for raising retiree pensions. For years, retirees had mobilized at UAW Bargaining Conventions, raising the demand that contract negotiations include COLA in pensions.

Although that had never been implemented, occasionally retirees received a “Christmas bonus” in lieu of COLA or even a slight raise in the pension formula.

This issue has particular relevance because many autoworkers have parents and grandparents who worked in the industry so there is a closer relationship among generations than in many other workplaces. There is also wide acknowledgement that the older generation fought for decent wages and benefits; it is the responsibility of the current workforce to support them.

Two other demands raised the issue of job security; less forced overtime and the right to strike over plant closures. Fain resurrected a UAW slogan — 32 hours work for 40 hours pay — and pointed out that workers should receive a benefit from automation.

These weekly presentations also announced what was happening in the other industries represented by the UAW, including 1,000 strikers at Blue Cross Blue Shield and the 4,000 strikers at Mack Truck. Successful organizing at new worksites was also a regular feature. These short announcements functioned to knit UAW members across various industries. It encouraged a sense of solidarity across the various sectors of the union — what Fain called the UAW family.

How to Strike?

As the September 15 strike deadline approached, presentations encouraged talking to coworkers about the unfolding negotiations. The union held practice sessions in locals and over Zoom demonstrating how to do this.

A revamped UAW website prominently listed the demands, latest news, and short videos where workers told their story spending years as a temp, sometimes forced to relocate to a plant far from home.

After the iconic hand shaking, an incident on Facebook Live, confirmed the UAW’s no-nonsense approach. Fain discussed Stellantis’ assertion of its right to close 18 plants and then threw the proposal in the trash can, remarking that’s where the contract proposal belonged. The gesture and remark went viral.

Entering the final stretch of negotiations, the UAW had always selected one corporation as its target. If negotiations didn’t produce a contract by the deadline, the UAW would strike the company’s facilities. Once the agreement was settled, it would become the template for winning a pattern contract at the other two.

But as Fain continued to discuss the profitability of all three, it became clear all were going to be targeted. Might all 150,000 members walk out all together? With a strike fund of $825 million, the union could afford $500 a week plus health care for a couple of months.

Or would we choose targeted strikes across the Detroit Three? In the 1990s when the UAW had targeted two GM parts plants, just 11,000 strikers were able to halt production across most GM facilities.

Two hours before the contract deadline this leadership announced a “Stand Up Strike” strategy of targeted strikes. Fain announced that workers in just three assembly plants — one from each corporation — would walk out. The UAW had fired its warning shot.

This approach provided the UAW negotiating committee with maximum flexibility in pressuring companies. It could expand the number of facilities going out on strike and escalate by targeting increasingly profitable companies. This guerilla tactic maximized chaos for the corporations while conserving UAW resources. UAW negotiators were in the driver’s seat as they forced corporations to compete with each other and were able to punish or reward them on a weekly schedule.

The Detroit Three were in the dark about which of their facilities would be targeted. Given the update schedule, corporations faced a weekly deadline to produce or face the another site being shut down. A positive response could be rewarded with a reprieve, but only until the following week.

The “Stand Up Strike,” was a strategy that put membership pressure on the corporations whether workers were striking or still working. Just as during the sit-downs of the 1930s, the energy built through the campaign leading up to the strike continued to build as everyone had a job to do.

While those still working were under expired contracts, members were encouraged to refuse all voluntary overtime, keep their eyes out for management attempts to alter procedures, wear red on Wednesdays and discuss the negotiations with coworkers. Many spent time on other UAW picket lines.

Workers found unique ways of sticking to the rules but not doing anything more. For example, at GM’s sprawling and very profitable Arlington Assembly plant, skilled trades workers decided to forgo riding bikes to their assignments. It took them considerably longer to arrive on foot, but there was no requirement to bike from one site to another.

This strategy is a variation on “work to rule.” Given how new it was for those still working to operate in unchartered territory and protect themselves from management reprisals, this technique requires less coordination. It gave workers a list of things they could do and an opportunity to be creative in applying them.

In addition to maintaining 24/7 picket lines, UAW members and community supporters attended rallies in Detroit and Chicago. During the first week, strikers at the Jeep plant in Toledo, Ohio caravanned to the Ford Michigan Assembly plant near Detroit, spent the afternoon picketing and then caravanned back.

This expression of solidarity was then matched by Michigan Assembly strikers caravanning to the Jeep plant. Once the strikers at the GM Wentzville plant near St. Louis heard about the caravans, they decided that with no striking plant nearby, they would caravan from one department of the complex to another.

This example of spontaneous striker initiative spread. The following week, with members at 38 GM and Stellantis parts distribution facilities on strike, UAW Local 51 on Detroit’s east side organized a car and motorcycle caravan to circle all the assembly and distribution centers in the area. The lead car stopped at every picket line, and Regional Director LaShawn English got out and shook every striker’s and supporter’s hand.

When negotiations are transparent and members feel empowered, spontaneous actions develop. So too with community involvement: witness the stacks of wood that appeared once autumn weather kicked in and burn barrels were set up.

Unions and a variety of organizations also worked to stock food pantries at local union halls, and made sure food and water went directly to the picket lines.

Keeping Active and Informed

This state of self-activity is in contrast with the past, when picketers were discouraged from talking to the media. We were told that if we said “the wrong thing” it might endanger the negotiations. This time the UAW president’s office organized at least one Zoom meeting to outline how members might effectively tell their stories to the press.

Every Friday thousands of autoworkers watched the Facebook Live updates to learn about the week’s negotiations and whether the strike needed to expand or hold firm.

With the UAW breaking with the tradition of keeping silent on negotiations, Ford and GM broke their silence and began to circulate videos in plant break rooms. The Detroit Three also told their side of the story to the press. But based on various surveys, majority sentiment across the country overwhelmingly supported striking workers.

Of the three corporations Ford was the most outspoken. As negotiations neared its final round, CEO Jim Farley complained that the UAW was asking for too much. As a guy who made $21 million plus stock options last year, he became a source of hours’ worth of picket line jokes.

The following week Bill Ford turned up at the Rouge complex, imploring workers to see themselves as partners with Ford management and in competition with the non-unionized, foreign-owned automakers.

When asked by the press for a response, Fain remarked that UAW members should see the non-unionized work force as their future union brothers and sisters. He emphasized working-class solidarity over nativist calls to make common cause with American billionaires.

That’s similar to the answer Fain had when Donald Trump said he’d come to Michigan to be with the workers. He urged them to stop paying their union dues. Objecting to Fain’s statement that green jobs should be good jobs, Trump announced that the UAW strategy would lead union members to joblessness. He, on the other hand, could “settle the dispute” and Fain could take a two-month vacation.

To all that, Fain remarked that Trump was part of the billionaire class that working people needed to fight.

When Trump came to Michigan, he didn’t go to a picket line but to a non-unionized parts facility where the press did not manage to find one striker in the crowd. They did locate a couple of autoworkers who supported Trump, but not his analysis of UAW strategy.

Pressure Produces Contract

When Fain invited everyone to join a UAW picket line, including the president, President Joe Biden went within a few days, the first sitting president to do so. A self-defined “car guy,” he made a statement in support of the right of workers to strike for higher wages. This moment closed off the possibility of having a federal mediator step in as a so-called “neutral” party. That was important for the UAW since federal intervention often forces a union into compromise.

As the strike was about to enter its fifth week, the UAW maximized the pressure on Ford by striking its most profitable plant, Kentucky Truck Assembly. This plant brings in $25 billion a year in revenue. That means it is producing $48,000 in revenue every minute of the work day. The strike was a surprise attack because previously strikes were announced during Friday updates, but this happened on Wednesday.

At that point there seemed to be two issues still on the table: pensions, and whether the joint ventures battery plants Ford is setting up would be covered in the contract.

With negotiations continuing at all three, the UAW announced that the companies had become used to Friday strikes and waited for last-minute negotiations. Chaos was now not just about which plant would be struck but also about the timing.

Next to go down was Stellantis’ most profitable plant, Sterling Heights Assembly Plant (SHAP) with GM’s Arlington Assembly the next day. Both plants bring in an annual $20 billion in revenue. With those additions, one-third of the Detroit Three UAW members were on the picket lines, two-thirds still at work, doing their part.

Within a day, fearing that the UAW might strike the Rouge Truck plant — where the country’s biggest selling truck, the electric F-150 is produced — Ford reached a TA with the union. Stellantis followed three days later. GM brought up the rear two days after that, but only after suffering one more profitable plant go on strike.

The Ford and Stellantis TAs are now available on the UAW website with GM soon to follow. Facebook Live presentations and local discussions are taking place; voting has begun.

All three agreements include a 25% wage increase (40% had been demand) and restoration of COLA. Temporary workers are to be made permanent within nine months (demand had been within 90 days) and eligible even as temps for benefits including a signing bonus. Once temps become permanent, they can reach top pay within three years, with their temp time counting. (It had previously taken eight years.)

Almost all of the demands were addressed, but except for restoring COLA not completely won. The hardest to win are post-retirement pensions and health care. That’s settled as far as the Detroit Three are concerned: They uploaded health care onto a Veba the union is responsible for and substituted 401ks for pensions.

This time they raised the percentaage of their contribution to 401ks, and didn’t require an employee match. Many workers believe 401ks are better — they are portable where pensions are not — so I didn’t see we had the strength or time to win on that issue.

Since fewer U.S. workers receive these benefits the UAW needs to think deeply about how we can fight for these benefits while also rededicating ourselves to Medicare for all and adequate social security.

In my opinion, the most important elements of the tentative agreements are:

• Restoration of COLA.

• The concrete steps taken to end the abuse of temps and bring up the wages of a multitiered work force. This includes bringing distribution parts facilities and a few other sites up to standard wages.

• Opening the door to the unionization of the joint-venture battery operations.

Ford agreed to bring its joint-venture plants in Marshall, Michigan and Tennessee into the contract when either the majority of UAW members transferred in or through card check. The Stellantis agreement recognizes the UAW at its new Belvidere battery plant by simply leasing them to work there.

Earlier GM had agreed to recognize the UAW at its joint-venture battery facilities, most of which are scheduled to open between 2024 and 2027. Previously an overwhelming majority of Lordstown battery workers voted to join the UAW and an interim agreement negotiated.

• Raising the issue of work/life balance, the union asserted that workers have the right to a life outside of work.

The slogan and its motivation got more resonance from workers than I thought possible in an industry where overtime is a given and too many workers rely on it. The actual result in this contract is small — establishing Juneteenth as a paid holiday and Ford’s offer for a two-week paid parental leave. Measly by the standards of European countries, it is breakthrough for U.S. industrial workers.

I think it is important to raise demands that might not be implemented but can raise the consciousness of the workers even beyond the specific workplace. It wasn’t possible to win some of the demands, but that may be possible when the union is stronger, more united and with a growing democratic and solidaristic culture.

The Eat the Rich T-shirt Fain wore to one of the updates embodied the fight of working people against corporate greed. This contract, and the struggle it took to win round one, is the best motivation for joining a union. The UAW forced the Detroit Three to agree to terms they had no intention of meeting.

Standing Up

The strategy underpinning the Stand Up Strike is to continuously bargain, pitting one corporation against another and exerting more pressure as each week goes by. While others hoped that all 10 demands could be fully implemented, most workers and labor observers thought winning a few would result in an extraordinary contract.

There may not be many such examples where a union can use one employer against another in negotiations, but escalating a strike and setting deadlines to produce maximum gains is certainly relevant. Announcing the progress of negotiations puts pressure on the corporations and keeps the members informed and eager to do their part.

Central to the organizing at both UPS and the Detroit Three was the call for the membership to shape their demands and prepare for their implementation in innovative of ways. Workers were encouraged to tell their stories so that the broader working class understood and supported their struggle.

During the UAW’s strike, trade unions around the world sent message of solidarity and delegations to rallies. Teamster drivers honored the picket lines while the Detroit Three sent their salaried workers across the line to scab.

These experiences will hopefully sustain the membership’s sense of empowerment, deepen its activism and broaden the bonds of solidarity. All will be critically necessary in the struggles ahead.

November-December 2023, ATC 227