Against the Current, No. 224, May/June 2023

-

Desperate Journeys. Sick System!

— The Editors -

In Defense of Being Awake

— Malik Miah -

Strange Career of the Comstock Law

— Dianne Feeley -

Anti-Trans Legislation, a Form of Reproductive Injustice

— Shui-yin Sharon Yam -

Frank Hamilton, the People's Musician

— David McCullough -

Earthquake Aftermath in Turkey

— Daniel Johnson -

Peripheries of Chinese Imperialism: Belt & Road Initiative in Jamaica

— Robert Connell -

Police Revolt & Hastings Street Tent City

— Ivan Drury - New Labor

-

Another Restructuring: A Challenge for the UAW

— Dianne Feeley -

The Future of Academic Unionism Will Play Out at the University of California System

— Barry Eidlin - The Struggle for Self-Determination

-

Songs and Flowers for Ukraine

— Oksana Briukhovetska -

A Discussion with Eyewitnesses: People's War in Ukraine

— Suzi Weissman interviews Vladislav Starodubtsev & Jeremy Bigwood -

From Ukraine to Palestine: The Poisons of Denialism

— David Finkel - Reviews

-

Exploring White Supremacy

— Bill V. Mullen -

The Price of Slavery

— Christopher McAuley -

No Mercy Here

— Alice Ragland -

Lac-Mégantic Rail Disaster

— Guy Miller -

The Working Class in Turkey Today

— Daniel Johnson - In Memoriam

-

Frank Thompson, 1942-2021

— Dianne Feeley

Dianne Feeley

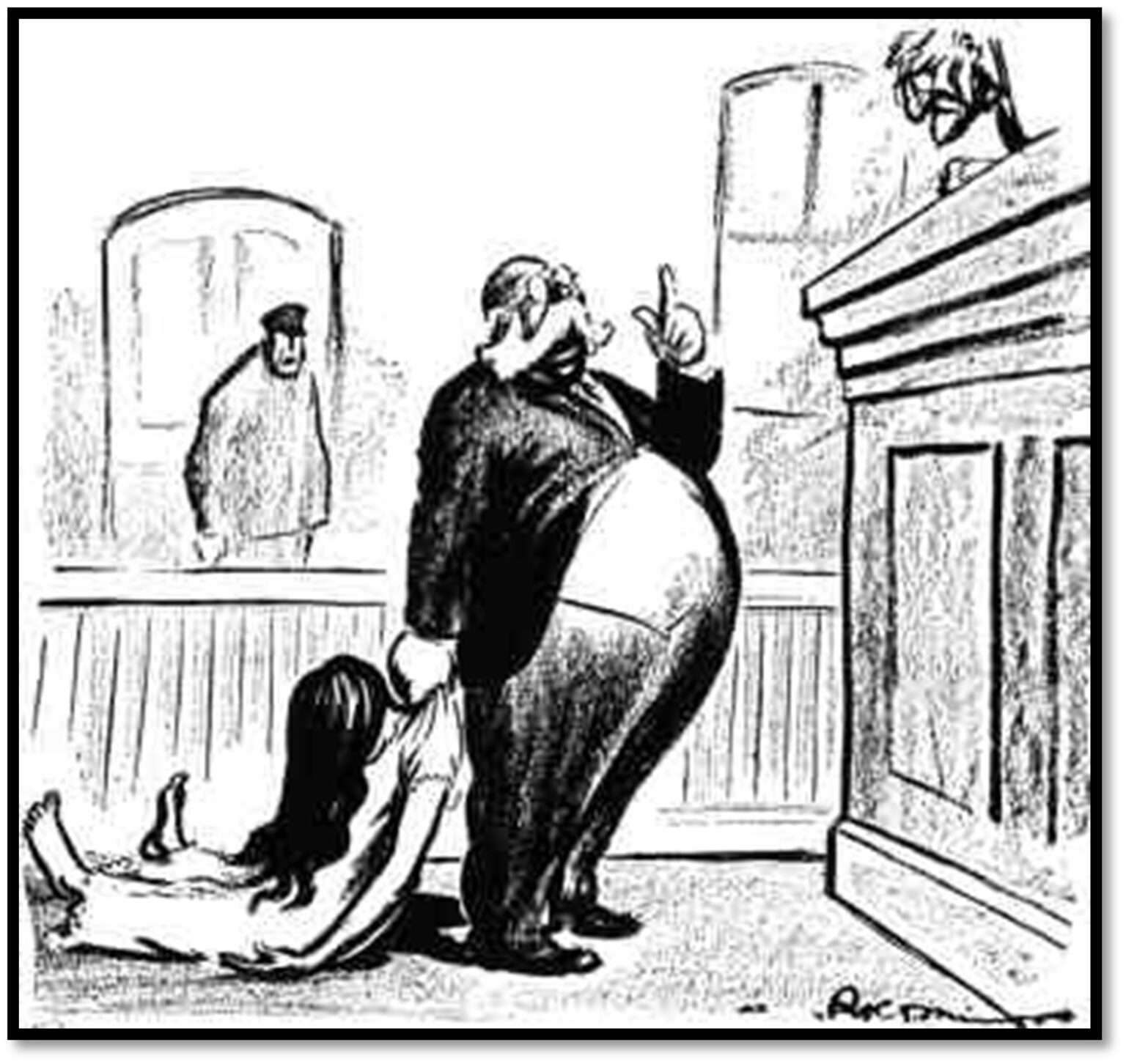

WHAT DOES AN 1873 “anti-obscenity” law have to do with women’s rights today? It may be a zombie, but the Comstock law lives on.

U.S. District Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk, in his April 4, 2023 decision, cites the law half a dozen times when challenging the Federal Drug Administration’s rule that medication abortions are safe and certified pharmacies can mail the prescriptions. The FDA, having loosened restrictions during the pandemic, determined it is unnecessary to pick up the prescription in person.

Earlier this year 21 rightwing state attorney generals threatened pharmacies who announced they would apply to be certified to distribute mifepristone. The 21 cited the Comstock law as the bedrock for their case.

Mifepristone, a drug approved by the Federal Drug Administration in 2000, is used in the United States as the first of a two-part medication abortion. It blocks the hormone progesterone from sustaining a pregnancy and dilates the cervix. The second pill, misoprostol, is taken one or two days later causing the uterus to contract and expel the pregnancy tissue.

This medical procedure is used in a growing majority of all U.S. abortions. It is safe — meaning no additional medical intervention is necessary for 95%-99% of all cases within the first 10 weeks of pregnancy. Over 100 studies have confirmed the safety of this two-part medication.

However Judge Kacsmaryk wrote an opinion that asserts mifepristone is unsafe. He accepts the plantiffs’ alternative reality that medication abortion is overwhelming the medical system and placing “enormous pressure and stress” on doctors.

He is absolutely certain that the Comstock law excludes the possibility of mailing any medication that could lead to an abortion, quoting the reactionary law:

“[e]very article or thing designed, adapted, or intended for producing abortion, or for any indecent or immoral use, and [e]very article, instrument, substance, drug, medicine, or thing which is advertised or described in a manner calculated to lead another to use or apply it for producing abortion, or for any indecent or immoral purpose.” (Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine vs. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, p. 32)

The conservative Fifth Circuit Court (two Trump-appointed judges out of the three), when partially overruling Judge Kacsmaryk ruled that given the Comstock law, mifepristone should not be mailed.

What Is the Comstock Law?

The 150-year-old federal law is named after Anthony Comstock (1844-1915), a leading member of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. While the law forbids distributing obscene literature by the U.S. Postal Service or by handing out these materials, it does not define what is obscene.

Nonetheless Comstock, in upholding “Christian morality,” saw these as including any book, manual or ad on aspects of reproduction (anatomical drawings, or books, pamphlets or devices for contraception and abortion) as well as about prostitution. There were no exceptions, even for nurses and physicians.

Comstock was then named special agent to enforce the law, serving from its passage until 1915. During that time he made 4,000 arrests and confiscated several tons of literature — much of it found stored in his home after his death.

Interestingly enough, a recent biography of a successful 19th century abortionist, Madame Restell, describes her use of both pharmaceutical and surgical methods. Arrested by Comstock in 1878, Restell slit her throat just before her trial.

More than a dozen other abortion providers, most not as wealthy as Restell, chose suicide as well. (See Madame Restell: The Life, Death, and Resurrection of Old New York’s Most Fabulous, Fearless and Infamous Abortionist, by Jennifer Wright.)

The Struggle for Voluntary Motherhood

In the early 20th century, as both single and married women increasingly worked fulltime outside their home, women’s need for knowledge about their bodies grew. A few nurses and doctors, particularly those affiliated with the Socialist Party, organized classes for women through the party’s women’s committees. These then led to producing the talks as articles in socialist newspapers.

Margaret Sanger, a nurse, authored a series of articles, “What Every Girl Should Know” for the New York Call. When her article on venereal disease was declared obscene by the post office, her column ran with its title and a box underneath saying “Nothing, by order of the Post Office Department.”

By March 1914 Sanger launched an independent monthly, The Woman Rebel. The paper discussed various problems working women faced and was distributed primarily at political meetings and workplaces. That August Sanger was served a nine-count indictment.

While awaiting trial, she wrote a 16-page pamphlet, Family Limitation. This was a direct challenge to Comstock Law — and she ordered 100,000 copies printed. Then she left the country, and through her speeches generated a favorable wave of international publicity. When she returned home the following year, the charges were dropped. Sanger savored her victory by launching a national speaking tour.

On her return she set up a birth control clinic in a working-class area of Brooklyn. Ten days later the clinic was raided; she and her sister were arrested. Charged under a state law similar to the provisions of the Comstock law, they served a month in prison. But by the end of World War I she had moved away from radicalism to focus on birth control. Sadly, she embraced eugenics as the rationale for her work.

Other radicals, including Dr. Antoinette Konikow, Rose Pastor Stokes and Emma Goldman, also wrote and spoke about women’s right to control their bodies. Konikow published “Advice to Mothers” in English, Italian and Yiddish (1923) and a pamphlet for physicians, Voluntary Motherhood (1923, 1926, 1928). Her 1931 book, Physicians’ Manual of Birth Control, contained text, drawings and tables.

During the 1920s Konikow gave an annual series of five classes on sex education and birth control to women only. She was arrested under a Massachusetts version of the Comstock law but found not guilty in Boston Municipal Court. (Her attorney pointed out that she had lectured but had not distributed contraceptives.)

To a certain extent the economic hardship of the depression legitimatized contraception. By 1930 the American Birth Control League operated 55 clinics; eight years later there were over 500.

Sanger’s ABC worked to put together the National Committee on Federal Legislation for Birth Control. The committee, made up of 1,000 organizations with a combined membership of 20 million, sued In federal court to lift restrictions on contraceptives.

At the 1936 trial Dr. Hannah M. Stone, medical director of the Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau in New York, testified that she had prescribed the use of contraceptive devices when it was not desirable for a patient to become pregnant. The United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit rendered a decision that the Comstock law did not apply to the legitimate activities of physicians. The government’s attorney chose not to appeal.

This decision knocked out a key provision of the federal law and swept away all but three state laws. (The three exceptions were Connecticut, Massachusetts and Mississippi.)

It was only in 1965 that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Griswold v. Connecticut that married couples have the right to privacy and the use of contraceptives. That right was extended to unmarried people in Eisenstadt v. Baird (1972).

But now that the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled in Dobbs v. Women’s Health Group of Mississippi that there is no federal right to abortion, a law that most people don’t even remember is being dusted off to oppose abortion by limiting its access.

Perhaps the Comstock law will also come in handy for banning books that Moms for Liberty types find “sexually explicit” and therefore inappropriate in libraries. With no explicit definition of obscenity, the law remains a valuable tool for the morality police. So far, the only exceptions that have been legally carved out are around birth control or when a book’s dialogue reveals the mind of a character — as in the case of James Joyce’s Ulysses (U.S. v. One Book Called Ulysses, 1936).

Although the battle against disseminating birth control information may seem won, in fact it is also under attack. We find rightwing legislatures demanding that birth control be excluded from mandatory insurance coverage. Some employers have successfully fought against including coverage under the plan they provide their employees. Another area of dispute is that right wingers falsely assert that some forms of birth control are abortifacients.

However, through most of human history birth control and abortion were not separate categories but various forms of control over one’s reproductive life. The Comstock law, like the Hyde and Helms amendments, needs to be buried. Today the struggle for reproductive justice demands that all these repressive laws be swept away.

May-June 2023, ATC 224