Against the Current, No. 222, January/February 2023

-

The Smoke Thickens

— The Editors -

Inequality, Gender Apartheid & Revolt

— Suzi Weissman interviews Yassamine Mather -

Workers' Protests in Early December

— Yassamine Mather -

Student Strikes, Regime Cracks

— Yassamine Mather -

Repression Continues to Grow in Nicaragua

— William I. Robinson -

Queering "A League of Their Own"

— Catherine Z. Sameh -

A Radical's Industrial Experience

— David McCullough -

A New Day for UAW Members?

— Dianne Feeley - Ukraine's War of Survival

-

Future Struggles in Ukraine

— Sam Friedman -

Russia's Road Toward Fascism

— Zakhar Popovych - Race and Class

-

The Black Internationalism of William Gardner Smith

— Alan Wald -

Movement Challenges

— Owólabi Aboyade (William Copeland) -

George Floyd, A Life

— Malik Miah - Police Murder and State Coverup

- Reviews

-

Out of the Two-Party Trap

— Marsha Rummel -

Feminists Tell Their Own Stories

— Linda Loew -

Working-Class Fault Lines in China

— Listen Chen - In Memoriam

-

Mike Davis, 1946-2022

— Bryan D. Palmer

Alan Wald

The Stone Face

By William Gardner Smith

Introduction by Adam Shatz

New York: New York Review of Books Classics, 2022, 240 pages,

$10.99 paperback.

THE STONE FACE, republished this past year after nearly six decades, remains a novel downright fearless in its quest to unsettle. A work of historical fiction, the book’s central characters are a tight-knit coterie of Black American expatriates in Paris during the months of 1960-61 when the Algerian Revolution for independence from France (1954-62) was reaching its climax. The insights may not all seem new, but they are profound, and many readers will find the storyline as startlingly radical now as it was in 1963.

Artistically, The Stone Face is a hybrid that is at once particular and capacious. To some extent it is a character study of Simeon Brown, a one-eyed African American painter and journalist with a Biblical first name frequently translated as “God has heard.”

Although Brown has relocated to France to escape the U.S. racism that cost him his eye in a violent confrontation, he is haunted by a need to make a political commitment in the early Cold War years of anti-colonial struggle and the Civil Rights movement.

A Cosmopolitan Political Militant

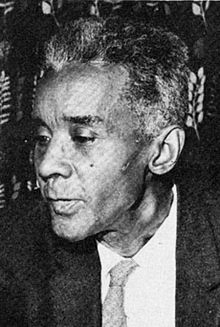

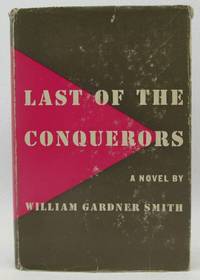

The precocious author, then 36 years old, was well-suited for an achievement of this intricate vision. Raised in South Philadelphia’s Black ghetto, William Gardner Smith (1927-74, called “Bill” by his friends) had already published three previous novels: Last of the Conquerors (1948), Anger at Innocence (1950), and South Street (1954).

In late 1951 he moved to Paris. After 1954 he was employed by the prestigious international news organization Agence France-Press (AFP) as its first African American reporter. This journalistic training enabled Smith to craft this fourth volume of fiction with the observed immediacy of a skilled reporter.

Yet there was something else: Smith had a background in postwar Philadelphia’s modernist cultural circles as a cosmopolitan political militant, one who collaborated with various organizations on the U.S. Far Left and was especially taken with the Trinidadian Marxist C. L. R. James (1901-89).

Shortly after James had declared Smith’s Last of the Conquerors to be the foremost voice of a new generation of radical Black writers in the pages of the Trotskyist journal Fourth International (March-April 1950), Smith announced himself with a similar albeit more elaborate artistic and political manifesto in W. E. B. Du Bois’ journal Phylon (Fourth Quarter, 1950). These two proclamations will be discussed at length in this review essay.

What is noteworthy right away is Smith’s experience of immersion in modern literature while negotiating among diverse ideologies and activists. This personal history may explain why Smith had the maturity to avoid facile categorizations and judgments, even when depicting those who rationalize a choice of personal peace and comfort over social solidarity. He also fashioned the connective tissue between seemingly incongruent populations while resisting too-easy universalisms and idealizations.(1)

The upshot of both talents — journalistic skill and a complex understanding of political conundrums and human actors — was an artistic sensibility that pushed borders, unbound by the limitations of predecessors.

The Stone Face circles around the dilemma of commitment in exile through segments called “The Fugitive,” “The White Man,” and “The Brother.” It’s a three-part structure that transports the melancholic protagonist through the Hegelian dialectical stages of a thesis (as a refugee from U.S. racism), antithesis (as an uneasy collaborator in French racism), and synthesis (through redemption by transnational solidarity).

Despite episodes of brutality and romantic disappointment, the progression becomes one of healing and achieving an emotional coherence in Simeon’s life. Throughout the novel Simeon has been laboring to paint an “inhuman” human image on canvas (13), a stone-like face of hatred that symbolizes bigotry. However, he tears this up at the end of the novel.

The narrative can also be read as a meditative exploration of relative privilege across the color line and the conundrum of racial identity and political solidarity apprehended from different angles. This provides a qualifying counter-theme for which the author weaves together multiple points of view — including African American, Polish-Jewish, Algerian, white American, and French.

There are frequent references to the Holocaust, deployed as a prototype of racist inhumanity at its worst. Simeon is visibly shaken by news of the 1960 overthrow by Black Africans of Patrice Lumumba, first prime minister of the Republic of the Congo. In early 1961, Lumumba is executed by a Katangan firing squad and Simeon stares in horror at the newspaper photographs of his killers: “Those faces! Those black faces!” (169)

In this respect the novel re-introduces us to disturbingly prescient material at exactly the right moment in our current era of fierce debates around identity and solidarity. In recent years these have taken the form of accusations of “race reductionism” (allegedly seeing group-specific anti-racist demands as the principle focus for ending oppression, attributed often to journalist Ta-Nehesi Coates) and “class reductionism” (allegedly concentrating on class-wide economic demands as an alternative, attributed customarily to Marxist scholar Adolph Reed).(2)

Smith’s novel commences its engagement with earlier iterations of these debates by bringing under scrutiny the unacknowledged complicity in France’s anti-Arab racial oppression on the part of the well-treated Black people — who bear more than a passing resemblance to the legendary Left Bank circle around novelist Richard Wright (1908-60) and the famed “Bootsie” cartoonist Ollie Harrington (1912-95).(3)

These ex-pats feel free in Paris because they rarely experience U.S.-style anti-Black prejudice, which they reckon to be the prime threat to their self-fulfillment. Such a narrow fixation on a color binary screens them from coming to grips with the material conditions of the Arabs, who, despite lighter skin and different hair texture, live in ghettos, face police brutality, and are shunned by the Europeans.

Nonetheless, Simeon’s perceptions change by the climax of the narrative, which features a recreation of the infamously bloody 1961 massacre of Algerian demonstrators by Parisian police that measures up to more than a few instances of racist butchery in U.S. history. He now finds that to live a life of principle, he must not only see the color line in another culture but also physically cross it.

In dramatizing Simeon’s choice to join the brutalized Arab protesters and be treated as one of them, The Stone Face puts forward the embrace of a class-centered yet non-reductive Marxist internationalism that ought to draw the attention of contemporary anti-racist and socialist activists.

Smith’s point is not to deny the particularities of anti-Black racism and other discrete forms of oppression that require redress through particularist demands; in fact, Simeon will ultimately opt to return to the U.S. to join the civil rights movement. Nevertheless, one must also be attuned to the sometimes tricky mechanisms involved in discerning the boundaries that truly separate the subjugated from the privileged, and potentially unify the former in resistance.

These are not always found by robotically pointing to color, nationality, gender, or even class background. On a global scale, at the very least, what separates out and unifies in struggle can also be in accordance with political principles, shared values, demonstrated commitments, and class interests held objectively in common.

Race and the Context of Class

The prose of The Stone Face is Hemingwayesque — concise, straightforward, and realistic. This enables Smith to depict the taut alchemy of U.S. racism in scenes occurring in flashbacks to Philadelphia and in encounters with white Americans abroad.

He aptly captures the omnipresent, simmering supremacist rage that quickly boils over into shocking violence: “everything was in slow motion. The boys stood around him…Chris [a Polish thug] toyed with a jagged switchblade knife….’Whatchu lookin at, nigger?’….Simeon screamed at the peak of his voice, falling to the pavement.” (31-33)

At the same time, through a carefully constructed sequence of split-screen parallels depicting the analogous treatment of Algerians in Paris and Black people in Harlem and South Philadelphia, Smith relies on a slow-building, pedagogical tension. This is necessary to dramatize how Black expatriates in Paris become “white” in regard to the treatment of Algerians:

“The police kept roughing up the Arabs, but they did not touch Simeon….The policeman put his arm on Simeon’s shoulder and said, ‘You don’t understand. You don’t know how they are, les Arabs. Always stealing, fighting, cutting people, killing….you’re a foreigner, you wouldn’t know.’” (54-56)

The political implications of The Stone Face thus can be parsed through at least two storylines. On the one hand, the horror of the anti-Black racist episodes makes the “identity politics” of Black unity plausible and necessary to Simeon and his expatriate friends.

To characterize oneself as “Black” in a white supremacist society is to move beyond an individualist perspective and define a collective predicament. Identity by race produces an alliance among those who face common forms of oppression, and the term itself (Black) moves over time from describing a stigma to a serving as a source of pride.

Smith certainly pulls no punches when it comes to depicting the intense pressure and all-pervasiveness of U.S. style white supremacism, which is hardly limited to specific acts of violence. As Simeon explains, “a hundred tiny things happen — micro-particles, nobody can see them but us.”

Beyond this, “there’s always the danger that something bigger will happen. The Beast in the Jungle, you’re always tense, waiting for it to spring.” He concludes, “we want to breathe air, we don’t want to think about this race business twenty-four hours a day….But…they force you to think about it all the time.” (76-77)

Yet the novel also argues that it is limiting to see the world exclusively through binaries of color, devoid of the contexts of class and colonial exploitation. In a narrow version of identity politics, one can suffer from a kind of political “linkage blindness,” missing the correspondence when it comes to apprehending discrimination in a different social configuration where the hierarchies of power and privilege are determined by economic and structural forces.

Not only does bigotry have no borders, but its forms can vary in disconcerting ways; a population persecuted in one culture may in a different society collude in the persecution of others. In The Stone Face, the progressive revelation of elements of the French domination of Algerians come to fit like puzzle pieces into a discernment of the broader political nightmare of European colonialism.

As Simeon takes a bus northward from the student quarter, he observes cheap stores, men hanging out on street corners, police everywhere: “’It was like Harlem….The men he saw had whiter skins and less frizzy hair, but….[t]hey adopted the same poses.” (87)

A Philadelphia Radical

The explanation for Smith’s unique transnational, double perspective partly derives from his earlier and profound immersion in specific Far Left experiences of his youth, an element insufficiently emphasized to date in the scholarly considerations of his achievement.(4)

A voracious reader and outstanding student at Benjamin Franklin High School, Smith graduated with honors at age 16 in 1944 but waived an opportunity to go to college in favor of starting a career as a journalist for the Pittsburgh Courier, an African American newspaper.

Two years later Smith was drafted into the postwar army; a period of basic training at Fort Meade, Maryland, was followed by an eight-month stint as a clerk-typist in occupied Berlin assigned to the 661st Truck Company. In this capacity he managed to send articles back to the Pittsburgh Courier reporting on the experience of Black soldiers, published under the by-line “Bill Smith.”5

Receiving an honorable discharge on February 19, 1947, he returned to Philadelphia and in March enrolled as a journalism student at Temple University on the G. I. Bill, soon finishing his first novel at age 21.

The Last of the Conquerors was a best-selling and widely reviewed, sensational story of an interracial love affair between a Black male soldier and a white German woman, a liaison that brings down the racist wrath of the U.S. army even as the Germans show relative tolerance.

The popular success of the novel brought a degree of financial security, enabling Smith to marry his high school sweetheart, social worker Mary Sewell, in June 1949, and get to work on his next literary project, one with all white characters called Anger at Innocence.

The European interlude, however, had awakened a more complex view of the workings of racism. This was followed by the development of a socialist political consciousness, not evident before. At Temple, where he spent two years, Smith encountered the iconoclastic philosophy professor Barrows Dunham (1905-95), best-known today for Man Against Myth (1947, First Edition) and Heroes and Heretics (1963).

Dunham had joined the Communist Party (CP-USA) in 1938, writing in the Party’s New Masses under the name “Joel Bradford.” In 1945 he quietly resigned from the Party, unhappy with the rightward trending policies of then general secretary Earl Browder.(6)

Nevertheless, Dunham remained a Marxist-Leninist, albeit one who expressed his ideas free of jargon. This can be seen in a chapter of Man Against Myththat most likely influenced Smith, “That There are No Superior and Inferior Races.”(7)

In a friendly, informal, and almost talkative style, Dunham focuses on stereotypes about Jews and African Americans, with frequent ironical parallels between Nazi propagandists and U.S. white supremacists like Mississippi Senator Theodore Bilbo. Dunham also remained an intransigent rebel. In 1953 he was fired from Temple, although tenured and chair of his department, for refusing to “name names” of alleged Communists before the House Committee on Un-American Activities.(8)

While Smith often attributed his initial political education to Dunham,(9) his notoriety as a successful author led to his and Mary’s apartment becoming a kind of intellectual salon that attracted an interracial group of writers and intellectuals. Among the African Americans participating was the future novelist Kristin Hunter (best known for God Bless the Child, 1964) and her husband, journalist Joseph E. Hunter.

Smith also developed a relationship with Irene Rose, an older white woman who traveled in radical political and cultural circles. An anti-Zionist Jew, Irene Rose was associated with Max Shachtman’s Workers Party (WP, which in 1949 changed its name to Independent Socialist League, ISL) and was considered an expert on the intricacies of various Marxist groups.(10)

Aesthetes and Revolutionists

Irene Rose and her husband, William Rose, had a friendship with African American artist Beauford Delaney (1901-79), who painted a notable portrait of Irene in 1944.(11) And it was Irene who in late 1949 introduced Smith to the aspiring African American writer Richard Gibson (b.1931), another Philadelphian albeit from the West Side, who was then a student at Kenyon College.

Gibson is best-known today as co-founder of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee in 1960, and also because he was exposed in Newsweek> magazine in 2018 as a collaborator with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) from at least 1965 to 1977. Nearly ten years after their friendship began, Gibson was to play a fateful role in Smith’s life.(12)

In the late 1940s, however, Gibson was an aesthete who felt more offended by the low level of U.S. cultural life than its racism, and engaged Smith in intense conversations about James Joyce, Marcel Proust, and Henry Miller. When I contacted Gibson in 2002 for information about Smith, he reported that they both admired Henry James’ The Art of the Novel: Critical Prefaces(1909) and favored Black novelist Chester Himes over Richard Wright.

Smith’s personal literary gods were Ernest Hemingway and William Faulkner, but he was quite taken with Ann Petry’s recent The Street (1946), and, surprisingly, the early 20th century social novels of Sholem Asch.(13)

Smith’s FBI file indicates that at the end of the 1940s he was actively in association with the Shachtman group and the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), and prior to that the Communist Party (CP-USA). Inasmuch as Smith was now a public figure, his involvement mainly took the form of aiding larger formations in which these organizations participated.

For example, Smith operated with the SWP’s working group in the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), in a temporary local body called “The Fred Simpson Defense Committee,” and in the “Civil Rights Defense Committee.” This last was set up on behalf of SWP member James Kutcher, a legless WWII veteran who had been fired from his government job for political reasons.

With the CP-USA, Smith worked with the Civil Rights Congress, especially on the case of “The Trenton Six,” African Americans sentenced to death for the murder of a white shopkeeper, and the Council for the Arts, Sciences and Professions, a Leftist cultural organization. By 1950, however, he was closest to the SWP, attending internal meetings and considered recruitable by the local branch leaders.

Due to his past association with the CP-USA, there was concern among some SWP members about Smith’s outspoken admiration for Soviet sympathizer Paul Robeson, but most of the local branch wanted Smith to represent the SWP in a delegation that planned to travel abroad in support of Yugoslavia in the recent Tito-Stalin split.(14)

A Trinidadian Marxist

Then again, the main attraction to Trotskyism may have been the Trinidadian-born revolutionary C. L. R. James (1901-89), who led a small political current inside the SWP known as the Johnson-Forest Tendency.(15)

James’ view that the African American population was destined to play a vanguard role in the coming socialist transformation had been promoted in the Trotskyist press in the late 1930s and was prominent again at this time through the publication of a powerful speech on “The Revolutionary Answer to the Negro Problem in the United States” and then a political resolution on the same topic, “Negro Liberation Through Revolutionary Socialism,” published in the December 1948 and February 1950 issues of the SWP’s Fourth International.(16)

Although writing mostly under pseudonyms and living in obscurity, James’ reputation as an erudite and creative thinker was well-known in Trotskyist political circles.

Around 1950 Smith, at least once accompanied by Mary, began making trips to New York to meet with James. According to Constance Webb (1918-2005), married to James at that time, the association lasted about a year. During passionate discussions over dinner, Smith seemed eager to learn, and the conversation was more about literature than politics.

In fact, Webb recalls that James discouraged Smith from organizational affiliation and activism, insisting that “Your business is to write.” To that end James reportedly recommended that Smith “expand his imaginative range, suggesting that he [Smith] learn French so that he could read the classics in their own language.”(17)

James then went on to discourse about “War and Peace, Anna Karenina, Crime and Punishment, Madam Bovary (one of his favorites)” and “analyzed the works of the Athenian playwrights.” He prepared a list of additional books for Smith to read, including those of famous literary critics, and then moved on to talking about “music, painting, sculpture, motion pictures….” Webb believed that James “introduced Bill to Richard Wright [already in Paris], Chester Himes, and Ralph Ellison.”

While the FBI alleged that Smith was a member of the SWP, there is no evidence (other than the opinion of an informer), and formal party affiliation seems unlikely. During the period in which Smith was visiting James, James’ followers in the SWP were in the process of splitting away from Trotskyism and by 1951 had launched a new organization called Correspondence.

It’s more likely that Smith, who favored collaboration with many groups, drew back from what he saw as organizational sectarianism. However, James’ impact on his thinking would become evident.

Two Young Writers

James’ essay about Smith appeared in the SWP journal in the spring of 1950 as “Two Young American Writers,” and was signed G. F. Eckstein. Here James pointed to Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead (1948) and Smith’s The Last of the Conquerors as respectively “brilliant” and “distinguished” novels, the work of writers “repelled by Stalinism, without cultivating any illusions about bourgeois democracy.” Although James presents no evidence to document this political characterization,(18) he was certain that the appearance of these first novels was “the unmistakable sign of a new wave of radical intellectuals.”

The bulk of the essay is essentially a comparison of Mailer’s novel with Herman Melville’s 1851 Moby Dick, something of a preview of James’ by now well-known Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and the World We Live In (1952). Here, as in that longer work, James argues that a central theme of the times must be to grasp the international power struggle between the capitalist West and Stalinism, requiring a third, independent proletarian force to achieve a socialist resolution.

Mailer, he observes, had almost succeeded in his novel; the fascist power of the West is well exemplified in the character Croft, but representatives of the alternative remained insufficiently realized among the dramatis personae.

Turning to Smith, James affirms that “for him as a Negro, the perspective of freedom, in relation to the Negro as he is, is a permanent part of his consciousness.” What James found central to Smith’s work was the theme of revolt, because the novel climaxes when “a Negro soldier, maddened by [racist] persecution, shoots an officer, and jumping into a truck, seeks some sort of existence different from that which tortures him — the most convenient place is the Russian zone.”

Yet The Last of the Conquerorsis limited in not being framed by a world-historic context, “the sense of a universal social crisis.” James then affirms that, nevertheless, both Mailer and Smith have met a precondition “of any artistic development,” which is “an uncompromising hostility to the values of Stalinism and to those of American bourgeois society.”

Together, these oppressing societies comprise an “enemy” which “must be seen in all its amplitude.” Each of these camps “poses an ‘either-or’ and seeks to encompass the whole field.” Mailer and Smith, fortunately, hold to a “systematic and truly philosophical opposition to the decay and perversions of these two barbarisms” so that there is hope that they “can find their way to those deeper levels which will nourish and not desiccate their talents.”(19)

An Age of Struggle

A few months later, Smith published “The Negro Writer: Pitfalls and Compensations,” which elaborated on many of these same topics. He began by embracing James’ observations about the limitation of The Last of the Conquerors.

The Black writer, explains Smith, “is under tremendous pressure to write about the topical and the transient — the plight of the Negro in America today.” While some such novels may achieve greatness due to historical interest, it is the “universal themes” one finds in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and Tolstoy’s War and Peace toward which one must aim.

Smith then moves to an argument of his own: To achieve art of this major type, the writer “must maintain emotional contact with the basic people of his society,” not become detached so as to move “in a rather esoteric circle…to some degree, into an ivory tower.”

Regrettably, in our contemporary political world, “The writer who is detached from society” does not perceive contradictions between “the individualistic and basically selfish ethic of Capitalism” and the “socialist tendency” gaining traction among ordinary people.

For the Black writer, this degree of detachment is less likely: “The very national prejudice he so despises compels him to remember his social roots, perceive the social reality….” Racist discrimination at every turn leaves him “bound by unbreakable cords to the Negro social group.”

At this point Smith revisits the argument proposed by James — the necessity of embracing the world conflict or the international power struggle. In a paragraph that might have been written by James himself, Smith explains: “We live…in an age of struggle between the American brand of Capitalism and the Russian brand of Communism…. But is this, really, the root struggle?”

He then launches into what is likely veiled autobiography, describing a young writer revolted by the “dog-eat-dog existence we glorify by the name of Free Enterprise…an existence which distorts the personality, turns avarice into virtue and permits the strong to run roughshod over the weak, profiteering on human misery[.]”

Citing Norman Mailer as an example of a writer “repelled” by capitalism and seeking “something which offers hope of a cure,” he affirms: “Today, at first glance, the only alternative seems to be Russian Communism.” However, “our young writer of intelligence and ideals” embraces Communism only to discover “the evils of dictatorship.”

He learns about “purge trials….He learns of the stifling of literature, art and music in the Soviet Union. He learns that Hitler is one day evil, the next day (following a pact with the Soviet Union) good, and the next day evil again.”

As the young writer flees from this alliance, “the advantage of the Negro writer is discovered.” That’s because, “in ninety-nine out of a hundred cases” the white writer (he cites John Dos Passos) will turn back to the “very decaying system which lately he had left, a system he now calls ‘Democracy,’ ‘Freedom,’ and ‘Western Culture.’”

In contrast, the Black writer “does not, in most cases, come back to bow at the feet of Capitalism. He cannot, as can the white writer, close his eyes to the evils of the system under which he lives.” Besides, “Looking at China, at Indo China and at Africa, he cannot avoid the realization that these are people of color, struggling, as he is struggling, for dignity. Again, prejudice has forced him to perceive the real, ticking world.”

Smith’s summary paragraphs express both components of James’ outlook — the vanguard role of Black America and essentially a Third Camp (“Neither Washington nor Moscow”) position toward the international power struggle:

“the Negro — and the Negro writer — rejects those aspects of both American capitalism and Russian Communism which trample on freedom and rights. Repelled now by both contending systems, the Negro writer of strength and courage stands firmly as a champion of the basic human issues — dignity, relative security, freedom and the end of savagery between one human being and another. And in this stand he is supported by the mass of human beings the world over.”(20)

Symbolism and Realism

This high degree of congruence between the views of James and Smith does not mean that the opinions of the former were artificially imposed on the latter. Smith’s experience in postwar Europe and his immersion in Marxism and modern literature in Philadelphia had already launched him on a course of critical cosmopolitanism.(21)

Additionally, negative experiences with the CP-USA and discussions with individuals such as Irene Rose had awakened his antipathy to Stalinism.(22) James, however, helped Smith firm up and refine his views, and to a significant extent clarified his self-concept as a Black radical artist.

How much of these views of 1950 made a lasting impact on Smith after his transit to Paris might be questioned. There is also reason to be dubious as to whether James’ political admonitions about what was mandatory for the health of creative writing were truly relevant to the production of memorable African American literature.(23)

In any event, Constance Webb believed that there was never any communication between Smith and James after 1951,(24) and his 1970 book Return to Black America makes no reference to James. Artistically, there was not a dramatic advance.

There is a consensus that Smith’s second and third novels failed to match the achievement of his first, although they do exhibit his gift at characterization. As one astute critic observed, “he [Smith] subjects his major characters to the kind of interior probing we associate more with the French, German, and Russian novelists than with American,” and also notes that there are themes and structures suggestive of Dostoevsky’s writing.(25) But the books remain out of print with little hope of rehabilitation.

In contrast, The Stone Face goes further than any of Smith’s earlier fiction in hinting at disturbing but submerged psychological depths provocatively intimated by the author. There are Simeon’s dream-like memories of incestuous longings for his sister and of a troubling rape-like sex game (“The Chase”) among the neighborhood children in Philadelphia; Simeon’s doppelgänger relation with the Algerian Ahmed, who takes up the armed struggle in his homeland even as Simeon professes that he quit the U.S. to avoid having to kill; the black eye-patch of Simeon and the dark glasses of his Jewish lover Maria that suggest a need to keep the horrors of the past partly out of sight; Maria’s cryptic reference to the personal pain experienced by her Nazi tormentor (79); and the haunting visage of the stone face on canvas that morphs in meaning between the universal and the specific.

What is more, the novel is set in the context of a world struggle, although the adversaries are Western colonialism and the anti-colonial resistance, not the “Free World” versus the Soviet Union.(26)

Stylistic ingenuity brings this project alive, especially when Smith’s symbolist interventions (haunting memories of Joey the drunk, ominous newspaper headlines from Africa and the United States, Maria’s references to the bad decisions and fate of her parents in the Holocaust) rub shoulders with passages of stark realism (police raids on Algerian homes, hostility from French patrons in a restaurant off-limits to Arabs, descriptions of torture and detention).

No one would suggest, however, that the novel achieved the stature of the major works of Tolstoy.

Politics Abroad

In Europe Smith possibly maintained some association with the Communist movement. Following a divorce from Mary not long after his arrival in Paris, his romantic partner for some years was Musy Hafner, the ex-wife of an official of the German Democratic Republic (GDR).

Hafner introduced Smith and Gibson (living in France after military service) to Bertolt Brecht when Brecht visited Paris for a theater festival in 1955.(27) Suspicions of Smith’s disloyalty were sufficient at this time for the U.S. government to refuse to renew his passport for a year after he made a 1956 trip to East Berlin.

His second wife, whom he married in 1961, was schoolteacher Solange Royez, a member of the French Communist Party (PCF). His third wife, beginning in 1971, was Ira Reuben, a Jewish woman from India.

Apparently, Smith maintained his critical view of Communism in private conversation. Smith told Gibson that he looked to Jean-Paul Sartre for wisdom far more than PCF leader Maurice Thorez, and in the late 1950s he was very supportive of Tito’s Yugoslavia against the USSR.(28)

The PCF’s position on the Algerian Revolution surely caused Smith dismay; the official view was that the 1954 insurrection was only about individual terrorism, and by the late 1950s well-known anti-colonial militants had left the organization.(29) But there is little published evidence of criticism of the USSR after his Phylon essay.

One passage in The Stone Face mentions anti-Semitism in the Polish Peoples Republic: “Poland is now Communist and is supposed to stand for equality for all, and it is still horrible to be a Jew there.” (122)

When Smith decided to make a drastic change in his political life in the 1960s, he turned to Africa, accepting an invitation from Shirley Graham Du Bois to move to Ghana and run the state television station. Smith and Solange arrived in 1964, where he joined poet Maya Angelou and novelist Julian Mayfield in Accra.

Regrettably, this idyll lasted for only 18 months before Nkrumah was overthrown in a military coup, and Smith returned to Paris and his previous job.(30) At this point he was privately espousing a kind of Third World Marxism. “I am for Castro and Mao Tse Tung [Mao Zedong],” he wrote his sister.(31)

In the summer of 1967, Smith visited Black radicals James and Grace Lee Boggs in Detroit, while doing interviews for his journalistic account Return to Black America. These were two of C. L. R. James’ one-time followers, whom Smith had first met around 1950, but they are not identified in the book as such and the material about them barely touches on international politics. Grace Boggs recounted in her autobiography that the couple then stayed in Smith’s apartment in Paris in June 1968, during the student-worker uprising, but no political conversations are reported.(32)

The Gibson Affair

Those seeking information on Smith’s political activities and views in France in the years leading up to The Stone Face are left with an unfortunate situation. A paucity of facts has led to an elevation of the importance of his association with “The Gibson Affair,” involving the aforementioned Philadelphia friend, Richard Gibson.

The rubric of “The Gibson Affair” refers to a series of incidents that has been described in many books and is too convoluted to recount in all its intricacies. But the essence is that a letter was published in the 21 October 1957 issue of Life magazine denouncing French colonialism and allegedly signed by expatriate Ollie Harrington. Since a foreign guest’s involvement in French politics, especially the Algerian conflict, could bring expulsion from France, Harrington immediately protested to the French authorities that the letter was a forgery and demanded an investigation by the police.

Within a short time, an authorized statement from Smith came into the hands of the police, affirming that the person who sent the letter to Life and forged Harrington’s signature was Gibson, who at that moment was working alongside Smith at the French press agency AFP. Gibson was then fired by the AFP and decided to return to the U.S. to seek other work. Just before Gibson departed, Richard Wright, suspicious for some years that “agents” of one sort or another were out to do harm to himself and Harrington, met with Gibson to seek an explanation for his behavior.

Gibson told Wright that it was Smith who had come up with the scheme to have well-known Black expatriates send letters in support of the Algerians to various publications, but with the idea that each would sign other people’s names.

This clever ruse would allow the individuals to legitimately deny responsibility for the letters if they were threatened with expulsion from France. According to Gibson, Smith immediately betrayed him by failing to inform Harrington and Wright of their plan, and then going to the French authorities and to AFP to blame it all on Gibson.

Apparently, Wright believed Gibson’s story and became convinced that Smith was indeed an “agent,” and that behind Smith was the hidden hand of C. L. R. James. This version of the episode became the basis for Wright’s final, unpublished novel, “Island of Hallucination,” in which characters partly modeled on Gibson, Smith, James Baldwin (who had nothing to do with any of this), and C. L. R. James comprise a network of secret spies and provocateurs.(33)

In 2003 Gibson stated to me that he had no explanation for Smith’s behavior in this fiasco and was desperate to know the facts. Several years after the events, Gibson was back in Paris for a visit and learned that Smith regularly took dinner at a brasserie called “Le Vaudeville” on the Place de la Bourse, near the AFP office. Gibson planned to encounter Smith there and finally learn the truth; but he approached Smith’s table only to have Smith run out of the restaurant yelling that he refused to talk to Gibson.(34)

Many aspects of the Gibson affair, including relevant FBI records, have been investigated by numerous biographers and scholars.(35) While Wright, Harrington, Smith, et al were certainly under surveillance in these years, no evidence has surfaced that any of the Black expatriates, including Gibson, were agents at that point;(36) Wright, on the other hand, himself had named some Communists to U.S. officials in 1954 in order to keep his passport.(37)

Considering Gibson’s later behavior, masquerading as a committed Leftist while giving information to the CIA, it seems possible that his version — that he was seduced by his friend into what appears to be a hare-brained ultraleft scheme — may not be the full story.(38)

The Return of October 17, 1961

The Stone Face, then, is the product of a long and complex history. A few of the most obvious sources come from news reporting undertaken by Smith. One is an article sent to the Pittsburgh Courier in 1954, where he first notes the similarity of the treatment of Black people in U.S. cities and Algerians in Paris.(39)

Another is a book, co-authored by Simone de Beauvoir, where the torture of an Algerian woman by the French — similar to that attributed to Smith’s characters Jamila and Latifa — is depicted.(40) A third is his recreation of the Paris Massacre of 17 October 1961, for which The Stone Face is the earliest known fictional treatment and one of the handful of representations of the event until the 1990s.(41)

The Paris Massacre was an intentional attack on a peaceful demonstration of 30,000 Algerians protesting a curfew imposed on them in Paris. The civil disobedience action was called by the French branch of the National Liberation Front (FLN), which advocated independence for Algeria.

The violent assault on the demonstration was orchestrated by Paris Police Chief Maurice Papon, who would later be convicted of “crimes against humanity” for his part in the Nazi collaborationist government in the Vichy region of France. As Smith graphically depicts the atrocity, over 200 Algerians were slaughtered by beatings and drownings in the Seine. For some, historical retrieval of these events is a main reason to engage Smith’s novel.

All the same, The Stone Face is not only remarkably clear-sighted about the persecution of the Algerians by the French government, but it focuses as well on a population of citizens who refuse to believe that they are racist. Several scenes dramatize the familiar go-to excuses for such denial.

In one instance Simeon queries his French student friend Raoul, “Is there racism in France?” Raoul responds immediately: “Of course not. The French don’t believe in racist theories; everybody knows that. Africans feel perfectly at home here. The French don’t understand racism.”

When asked specifically about the Arabs, Raoul goes on: “That’s different. The French don’t like the Arabs, but it’s not racism. The Arabs don’t like us either. We’re different” (65). Raoul, however, is balanced by a “race traitor”— another student, named Henri, who secretly works with the Algerians.

Smith is also candid about Black expatriates in France who made excuses for standing on the sidelines of the Algerian conflict. In a discussion with Babe Carter, the African American owner of a bookshop, Simeon points to the conditions in the Arab ghetto north of Paris and declares: “Seems to me that the Algerians are the niggers of France.”

Babe protests, “It’s not the same thing….Algerians are white people. They feel like white people when they’re with Negroes, don’t make no mistake about it. A black man’s got enough trouble in the world without going about defending white people” (105).

Nor does Smith suggest that the Algerians themselves are free of prejudice. Although Simeon is welcome among them after shedding an initial aloofness, his lover Maria finds herself confronted with crude anti-Semitism by two political militants named Ben Youseff and Hossein. The latter declares that he hates Jews, “Worse than I hate the French! Worse than I hate the colonialists!” (122)

Simeon, his friend Ahmed, and a white American named Lou all jump in to rebut the charges and try to give historical explanations for Jewish behavior in the Middle East and Algeria. Hossein retorts: “There are historical reasons for everything, even for the French occupation of Algeria, even for slavery….I just judge by the end products” (124).

Leaning into Ambiguities

These are some of the troubling conundrums observed in The Stone Face. Smith also gives fair-minded representations of the reasonings of those who simply refuse to follow Simeon’s unrelenting gravitation toward political commitment.

When Simeon finally announces to Babe that he intends to return to the United States to join the fight of the civil rights movement, Babe, a jaded former NAACP official, retorts: “But fight for what? For integration? Man, I don’t want to be integrated! I don’t want to be dissolved into that great big messed-up white society there” (145).(42)

Likewise, Maria is never condemned for her choice of pursuing fame and fortune as a Hollywood star. On the contrary, her distrust of making personal sacrifices to improve humanity seems understandable considering the horrors experienced by her and her family in the Nazi hellscape and the persistent anti-Semitism even among those who would want her collaboration — Polish Communists and Algerians.

This may be why Maria tells Simeon, on the eve of her eye surgery, that she would rather go blind than have full sight restored. For the most part, Smith’s approach is to lean into such paradoxes and ambiguities, not to run from them.

Yet there is at least one exception. Although Smith makes clear in his depiction of anti-Semitism among the Algerians that movements of the oppressed are not without flaws and can have many layers of nuance, he draws back from any reference to the violent civil war between the FLN and National Algerian Movement (MNA, formed in 1954 by the father of Algerian nationalism, Messali Hadj, 1898-1974).

According to Gibson, Smith was in the early years of the Algerian Revolution a strong partisan of the MNA, which had a reputation as being closer to Marxism, more working class, and influential in Paris.(43)

In fact, this was the view of many Trotskyist groups, including both the SWP and the ISL in the United States, the libertarian communist Daniel Guérin (1904-88), and a party led by Pierre Lambert (Pierre Boussel, 1920-2008) in France that had close contacts with Messali. Only the Internationalist Communist Party (PCI) associated with Pierre Frank (1905-84) and Michel Pablo (Michalis N. Raptis, 1911-96) held a distinctly different perspective; it advocated unity of the two rival currents, not cutting off relations with the MNA but leaning toward the FLN.(44)

Those in France who might be most closely associated with C. L. R. James, the group “Socialism or Barbarism,” also held a complex and less definable position, but tended toward an increasing hostility regarding what might happen if the FLN were to be victorious.(45)

The rivalry was not just in polemics. Over 300,000 Algerians and 25,000 French military died in the anti-colonial struggle, but among the insurgents the FLN regarded the MLN as traitors and determined to wipe them out as well. Perhaps 4,000 people were killed in mainland France and 6,000 in Algeria as the two factions clashed.(46)

The general stance of much of the French Left at the time was to keep quiet about the matter, and Smith seems to follow in like manner in his novel. Sadly, it is long past the time for this informational blackout to expire and activists today need to recognize that, in the colonial revolt, repression and torture have not been the exclusive behavior of European colonizers and imperialists.(47)

Committed Literature

Imperfect as he was, Smith should nevertheless be appraised favorably as an artist who aspired to embrace and to be in the world in accordance with his moral and political convictions, although his life was shortened due to death from cancer at the age of 47.(48)

In an astute essay on “Form and the Anti-Colonial Novel,” novelist and Harvard professor Jesse McCarthy observes that “Smith was not a theorist or a philosopher,” but he designed The Stone Face as an attempt “to narrativize intersectionality, to show how a critical apprehension of it as a lived experience might be a necessary, if not sufficient, condition for any form of emancipatory politics.”49

“Intersectionality” is a term coined in 1989 by Critical Race Theory scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, with its roots in feminism, to address systems of inequality interacting to create unique effects. McCarthy convincingly demonstrates how this is imagined in new ways in The Stone Face, but the thread that runs through Smith’s project is also about narrativizing “BlackInternationalism.”

On the one hand, gender issues receive comparatively short shrift in The Stone Face, although they are far from absent. On the other, the novel’s progression covers the experience of racial/national oppression lived by an African American male to a choice of being a citizen of the world.

In fact, the linkage by which Simeon connects the Algerian anti-colonial movement to the U.S. Black Civil Rights movement recalls the ways in which African American volunteers in the Spanish Civil War linked anti-fascism to battles against racism at home.

As University of Glasgow scholar David Featherstone points out in a study of anti-fascism and Black Internationalism, “through solidarities with other struggles…ways of refusing and challenging the racial divisions of U.S. society were envisioned and articulated.”(50) Thus, when Simeon decides to join with U.S. civil rights activists, he calls them “America’s Algerians” (204).

What we now call “identity politics” is not condescendingly dismissed by Smith but propelled forward to a higher stage of understanding. Through carefully chosen episodes, no one reading The Stone Face can accuse Smith of downplaying the specifics of anti-Black racism at any point. Yet the author manages to integrate Simeon’s acute consciousness of confronting a racialized capitalism with a Marxist and class perspective.

When Simeon becomes an internationalist, he has an enhanced understanding of how the group-specific struggle for school integration and voting rights is part of a world-wide movement for liberation. Moreover, in this development Simeon is helped along by his white American friend Lou, clearly intended to be a reliable ally and perhaps an avatar of socialist comradeship.

At a crucial point in the debate with the Algerians over anti-Semitism, it is Lou who follows Lenin’s dictum to “patiently explain”: “Lou intervened, speaking gently, because he was the only ‘pure’ white person there. ‘Every oppressed group is oppressed in a different way and has a different history.’” (123) Later, when Simeon tells Lou that he is returning to the United States, Lou replies: “I’ll meet you back there, and we’ll help to turn the States into a place nobody will want to flee.” (206)

There is no suggestion of rigid Leninist orthodoxy in any of this. It is more likely that Simeon walked out of the pages of Jean-Paul Sartre’s famous What is Literature? (1948) as the avatar of littérateur engagée (committed literature). An Existentialist aura permeates The Stone Face; one cannot count on a safe passage through life and each of us has the choice to speak up and act with authenticity and courage or succumb to mauvaise foi (“bad faith” — yielding to external pressures and adopting false values so as to disown one’s innate freedom).(51)

Smith wrote his book with cool self-control, but he also makes it clear that the road to understanding can be grueling. Above all, in his treatment of Simeon’s political progression, through forceful and sometimes eloquent rethinking, Smith has remolded historically specific political events of 60 years ago into ideas durable enough to be transmitted to future generations of activists for our own use. This is among the maximum imaginable attainments of a committed revolutionary artist.

Notes

- See the excellent discussion in Michael Rothberg, Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2009): 227-266.

back to text - The polemical and scholarly literature on these matters is far too extensive to summarize. An example of an attack on alleged “class reductionism” can be found in the article by Tattiana Cozzarelli, “Class Reductionism is Real and It’s Coming from the Jacobin Wing of DSA” at: https://www.leftvoice.org/class-reductionism-is-real-and-its-coming-from-the-jacobin-wing-of-the-dsa. An example of the argument against alleged “race reduction” can be found in the book Toward Freedom: The Case Against Race Reductionism (2020) by Toure Reed, the son of Adolph Reed. I admit that I was politically schooled in the notion that race and class demands can and should go hand-in-hand; my views are elaborated in “Race and the Logic of Capital”: https://againstthecurrent.org/atc192/p5183/

back to text - See James Campbell, Exiled in Paris (1995) and Tyler E. Stovall, Paris Noir (1996).

back to text - The major biographical source on Smith is LeRoy S. Hodges, Portrait of an Expatriate: William Gardner Smith, Writer (1985), which has no mention of the influence of Barrows Dunham or C. L. R. James, or anything substantial about the Trotskyist influence on Smith, or his association with Algerian factions, which are the main original contributions of this present essay.

back to text - See the information recorded by Khary Oronde Polk at https://www.interimpoetics.org/384/khary-oronde.polk

back to text - Ellen W. Schrecker, No Ivory Tower: McCarthyism and the Universities (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 59.

back to text - Barrows Dunham, Man Against Myth (New York: Hill and Wang, 1962), 85-116.

back to text - See Fred Zimring, “Academic Freedom and the Cold War: The Dismissal of Barrows Dunham from Temple University,” Ph. D. Dissertation, Teachers College, Columbia University, 1981, online at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/303113735?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true

back to text - The impact of Dunham was first mentioned to me in a phone interview with Mary Smith, 9 September 1986, and repeated in a 13 December 2002 e-mail to me from Richard Gibson: “His [Smith’s] political education does not start until his return to the United States, and he often spoke of his gratitude to Barrows Dunham for that.”

back to text - Irene Rose is mentioned in the Shachtman group’s Labor Action as an activist in the American Committee for European Writers, supported by both the WP and SWP: https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/laboraction-ny/1947/v11n19-may-12-1947-LA.pdf

back to text - See: http://lesamisdebeauforddelaney.blogspot.com/2017/01/beaufords-portrait-of-irene-rose.html

back to text - See: https://www.newsweek.com/richard-gibson-cia-spies-james-baldwin-amiri-baraka-richard-wright-cuba-926428. The Central Intelligence Agency’s files on Gibson are available at: https://documents.theblackvault.com/documents/jfk/NARA-Oct2017/NARA-Dec15-2017/124-90146-10107.pdf. See also the informative article by Charisse Burden-Stelly, “Stoolpigeons and the Treacherous Terrain of Freedom Fighting” at: https://www.aaihs.org/stoolpigeons-and-the-treacherous-terrain-of-freedom-fighting/. So far there is no evidence that Gibson was a spy during his years in Philadelphia or Paris, or during the time he was active in the Fair Play for Cuba Committee (1960-62). Gibson is still alive in London. For most of his life he was primarily employed as a journalist for mainstream as well as Left publications; he is the author of Mirror for Magistrates: A Novel (1958) and African Liberation Movements (1972).

back to text - The preceding information about Smith’s relationships and reading is based on a 14 December 2002 e-mail to me from Gibson.

back to text - Smith’s FBI file is now online at several locations in different forms and degrees of completeness. The version I have consulted is available at: http://omeka.wustl.edu/omeka/files/original/bc239307ad221891787c64a64258d7f1.pdf

back to text - “Johnson” was James and “Forest” was Marxist-Humanist founder Raya Dunayevskaya (1918-87).

back to text - See the informative discussion by Scott McLemee and a reprint of the text of the 1948 speech at: https://isreview.org/issue/85/revolutionary-answer-negro-problem-united-states/index.html

back to text - Letter from Constance Webb to Wald, undated but probably September 1997.

back to text - Nevertheless, the characterization was accurate for both. Mailer had been a Communist fellow traveler but was recently influenced toward anti-Stalinist communism by his Polish-born French translator, novelist Jean Malaquais (1908-1998), who was also a friend of James.

back to text - The quotations are from G. F. Eckstein [C. L. R. James], “Two Young American Writers,” Fourth International XI, No.2 (March-April 1950): 53-56. Max Shachtman’s Independent Socialist League also reviewed he Last of the Conquerors, but only briefly. See James M. Fenwick (Chalmers Stewart), “Novel Explores Theme of Negro GI’s in Germany,” Labor Action, 15 August 1949, 3. While the SWP’s Militant did not review Last of the Conquerors, in 1964 it published a favorable commentary on The Stone Face by Ethel Block: https://themilitant.com/1964/2807/MIL2807.pdf

back to text - The quotations are from William Gardner Smith, “The Negro Writer: Pitfalls and Compensations,” Phylon XI, No. 4 (Fourth Quarter, 1950): 297-303. This essay was reprinted in C. W. E. Bigsby, The Black American Writer, Volume I: Fiction (1969), 71-78.

back to text - See the application of this concept to Smith in Alexa Weik Von Moser, Cosmopolitan Minds: Literature, Emotions and the Transnational Imagination (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014), 89-119.

back to text - Gibson believed that Smith had thought of joining the CP-USA but was repelled by the literary culture of the movement. Email from Gibson to Wald, 13 December 2002.

back to text - Without getting into a detailed debate on the matter, it’s worth noting that many world-class artists of Smith’s Day were partisans of the Soviet Union — Pablo Neruda, Pablo Picasso, Bertolt Brecht, Mikhail Sholokhov, and Diego Rivera for starters. James’ observations about Melville and Mailer are stimulating and memorable, but the creative process and the development of craft are far more complicated than his postulation of a political precondition suggests.

back to text - According to Ralph Dumain, a specialist in the James archives, there appears to be an undated note from Smith to James praising the publication of Indignant Heart: A Black Worker’s Journal (1952) by Charles Denby (Simon Owens, 1907-83), a Johnson-Forest Tendency supporter. E-mail from Ralph Dumain to Wald, 27 September 1997.

back to text - Jerry H. Bryant, “Individuality and Fraternity: The Novels of William Gardner Smith,” Studies in Black Literature (Summer 1972): 1.

back to text - Of course, the ideological supporters of the “Free World” saw the anti-colonial struggle as mainly a proxy war with the Soviet Union, but Black American radicals saw much of the conflict differently, with the Third World seeking independence from the racist West. See Vaughn Rasberry, Race and the Totalitarian Century (2016).

back to text - E-mail from Gibson to Wald 17 December 2002.

back to text - E-mail from Gibson to Wald, 14 December 2002.

back to text - See: https://jacobin.com/2016/10/pcf-french-communists-sfio-algeria-vietnam-ho-chi-minh

back to text - For a thorough view of the Ghana episode among Black expatriates, see Kevin K. Gaines, African Americans in Ghana (2006).

back to text - Michel Fabre, From Harlem to Paris: Black American Writers in France, 1840-1980 (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 251.

back to text - Grace Lee Boggs, iving for Change: An Autobiography (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998), 140.

back to text - Among the most informative discussions of the novel is one by Richard Gibson himself, “Richard Wright’s ‘Island of Hallucination’ and the ‘Gibson Affair,’” in Modern Fiction Studies 51, No. 4 (Winter 2005): 896-920.

back to text - E-mail from Gibson to Wald, 13 December 2003.

back to text - Among the cleverer investigations of Smith’s FBI records can be found in William J. Maxwell, F. B. Eyes: How J. Edgar Hoover’s Ghostreaders Framed African American Literature (2015).

back to text - See Craig Lanier Allen, “Spies Spying on Spies Spying: The Rive Noire, the ‘Paris Review,’ and the Spector of Surveillance in Post-War Literary Expatriate Paris, 1953-1958,” Australasian Journal of American Studies 35, 1 (July 2016): 29-50.

back to text - Cited in James Campbell, “The Island Affair,” Guardian, 7 January 2006: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2006/jan/07/featuresreviews.guardianreview25

back to text - One of the better reports on the Gibson affair can be found in James Campell, Exiled in Paris (New York: Scribner, 1995), 199-205. Among the many aspects complicating the matter are that Gibson and Harrington had had a fistfight over ownership of an apartment; Smith seemed to believe that Wright himself was an agent; Chester Himes was suspicious of Smith as an opportunist and also as a possible agent; and Gibson held that Smith was inspired by an Algerian co-worker at AFP named Jean Chanderli. While I am dubious about Gibson’s version of “The Gibson Affair,” I have been able to independently corroborate most of the biographical information he has provided about Smith.

back to text - This is quoted in the excellent introduction to the 2022 edition of The Stone Face by Adam Shatz, xv.

back to text - Simone de Beauvoir and Gisèle Halimi, Djamila Boupacha: The Story of the Torture of a Young Algerian Girl which Shocked Liberal French Opinion (1962).

back to text - The depiction of the massacre is one of the reasons that the novel was never published in French until 2021, when it was issued as Le visage de pierre.

back to text - There has been a separate debate over Simeon’s decision to return to the U.S. rather than remain in France to fight for the Algerian cause. Most notably, in Paul Gilroy’s Against Race: Imagining Political Culture Beyond the Color Line (2000), it is argued that this decision contradicts the logic of the novel’s transnational solidarity. Many critics have argued against this, and there is evidence that Smith changed the ending of the novel (which was originally that Simeon decides to move to Africa) at the request of his publishers. These matters are discussed in Anand Bertrand Commissiong, “Where is the Love? Race, Self-Exile, and a Kind of Reconciliation,” Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 21, 1 (Spring 2021): 27-46.

back to text - E-mail from Gibson to Wald, 13 December 2002.

back to text - See the debate between Patrick O’Daniel (Sherry Mangan) and Philip Magri (Shane Mage) in the 1958 Discussion Bulletin of the SWP: https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/document/swp-us/idb/swp-1946-59/db/v19n02-apr-1958-db.pdf

back to text - See the writings on Algeria by Jean-Francois Lyotard on this website: http://www.notbored.org/SouBA.pdf. Thanks to Scott McLemee for pointing this out.

back to text - For further information see the article by Andrew Coates: https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/931/new-chapter-in-human-liberation and the review by Ian Birchall: https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/birchall/2004/xx/pattieu.html

back to text - However, it should be noted that the aforementioned articles in Footnote 41 from the SWP Bulletin do refer to the violence of the Algerian national liberation factions.

back to text - The fullest discussion of Smith’s final years can be found in Michel Fabre, From Harlem to Paris: Black American Writers in France, 1840-1980, 238-256.

back to text - Jesse McCarthy, “Form and the Anticolonial Novel: William Gardner Smith’s The Stone Face,” Novel: A Forum on Fiction 55, 1 (2022): 78.

back to text - See David Featherstone, “Black Internationalism, Subaltern Cosmopolitanism, and the Spatial Politics of Anti-Fascism,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 103(6): 1417.

back to text - For additional perspectives on Existentialist themes, see McCarthy, “Form and the Anticolonial Novel: William Gardner Smith’s The Stone Face,” Novel: A Forum on Fiction, 61-93.

back to text

For unexplained reasons Smith either changed his mind about the Yugoslavia delegation or it was cancelled. Some of Smith’s activities are mentioned in issues of the SWP newspaper, The Militant. See “Philadelphia Meeting Hits Police Assault on Civil Rights,” where Smith is described as speaking at a meeting chaired by SWP organizer Max Geldman: https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/themilitant/1949/v13n15-apr-11-1949.pdf; and “Mass Meeting Protests Police Brutality”: https://www.themilitant.com/1950/1435/MIL1435.pdf

back to text

January-February 2023, ATC 222