Against the Current, No. 222, January/February 2023

-

The Smoke Thickens

— The Editors -

Inequality, Gender Apartheid & Revolt

— Suzi Weissman interviews Yassamine Mather -

Workers' Protests in Early December

— Yassamine Mather -

Student Strikes, Regime Cracks

— Yassamine Mather -

Repression Continues to Grow in Nicaragua

— William I. Robinson -

Queering "A League of Their Own"

— Catherine Z. Sameh -

A Radical's Industrial Experience

— David McCullough -

A New Day for UAW Members?

— Dianne Feeley - Ukraine's War of Survival

-

Future Struggles in Ukraine

— Sam Friedman -

Russia's Road Toward Fascism

— Zakhar Popovych - Race and Class

-

The Black Internationalism of William Gardner Smith

— Alan Wald -

Movement Challenges

— Owólabi Aboyade (William Copeland) -

George Floyd, A Life

— Malik Miah - Police Murder and State Coverup

- Reviews

-

Out of the Two-Party Trap

— Marsha Rummel -

Feminists Tell Their Own Stories

— Linda Loew -

Working-Class Fault Lines in China

— Listen Chen - In Memoriam

-

Mike Davis, 1946-2022

— Bryan D. Palmer

David McCullough

MY ROOTS WERE in Texas but war and the New Deal took the family from Dallas to Washington, D.C. where I grew up as a liberal Democrat. My first political experience was getting punched in the nose for wearing a Truman button.

Our family was middle of the white middle class. High school sports were segregated until my last two years of high school, 1955-57. In 1960, Berkeley attracted me as an inexpensive place to get a doctorate in philosophy and pursue a teaching career.

I joined the Independent Socialist Club (ISC, founded 1964) in Berkeley in February, 1966. The Free Speech Movement (FSM) in 1964 radicalized me and got me into unionism as a founder of the first teaching assistants union, Local 1570 of the AFT.

Jumping between the student radical, civil rights, union, counter-cultural and antiwar movements in 1965 scattered my activist energy; joining an ongoing radical organization allowed me to concentrate it. But joining an independent socialist sect just moved the problem of scattered energy to the next level.

The ISC and then the International Socialists (IS, founded 1969) were valuable because they were movement organizations.(1) Our animus was to carry the movements we were involved in further and bring them into conscious confrontation with the “system.” But it became clear from the system’s violent reaction to challenges from the Black Liberation, antiwar and student movements in 1968-70 that none of them alone or in combination had the social power to win.(2)

Our own tiny energies had to be concentrated and rooted in the only force on the planet that could confront capitalism and win: the working classes.

I decided in 1969 to throw in my lot with the proletariat. I knew it meant tossing the social safety net enjoyed by the professional middle classes and unavailable to the working class — credentials, social networks, relative immunity from state brutality.

I went to work as a wireman at Western Electric in Oakland. I lasted two weeks short of the six months needed to have “seniority” and union protection. In that time I produced a newsletter, organized my work crew in a slowdown to force our steward (also our foreman) to quit and be replaced by one of us, planned the democratization of our local, and found allies in the same building among long-distance operators working for Ma Bell.

The CWA business agent sussed me out and fingered me to management. Union and management reps laughed as they walked me out of the building, fired for not mentioning an assault on a police officer conviction in my application.

By this time the IS committed to industrializing the organization.(3) Whether or not individual members took jobs in key industries,(4) the group committed itself to supporting and leading the work of those who did.

Jack Weinberg, of FSM fame, had worked out a detailed plan for getting IS members into UAW plants in Detroit. My work as a wireman at Western Electric and then at ITT(5) in 1969-70 was persuasive that there was a mood in the working class for moving beyond inherited norms of action on the job.

IS cadre had developed some useful skills in the ’60s — writing, producing and distributing pamphlets; calling and chairing meetings with agendas and meaningful democratic participation; networking with radicals from other organizations; keeping information flowing among our collaborators; creating slogans and memes that crystalized dynamic ideas; analyzing balances of power so we could decide when to move and when to hold back.

We decided that we could take these skills, plus our commitment, to advanced sectors of the 1970s U.S. working class, and make them useful and welcome to our new co-workers. The advanced sectors in January 1971, when I moved with my family to Detroit, were steel, auto, Teamsters and other transport workers like railroad, communications, miners and government workers.

Some had militant early traditions, some were in motion at the moment, such as the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM) and Eldon Avenue Revolutionary Union Movement (ELRUM) Black Power uprisings in the auto plants.

Early 1970s Detroit

I worked in the blast furnace division of a steel mill while waiting for a UAW job to open in 1971. The coke oven was filthy work, but fun at times. I particularly liked driving the locomotive which caught molten coke as it spilled out of the ovens into my coal car to be quenched.

I flunked the Ford physical but made it into Chrysler’s Warren Stamping Plant as a spot welder on an easy job, feeding door headers (where the windows wind into) on the door assembly line. An Appalachian worker hired in my cohort described the environment as “organized insanity.” After a few weeks I understood the Maoist saying “a grain of rice is a bead of sweat is a drop of blood.”

Everyone who worked in plants like that, or these days at Amazon and UPS, understood intuitively that the system was designed to drain every calorie of energy it could from you before releasing you to recover overnight. The highfalutin’ Marxist word “exploitation” is experienced more simply as getting squeezed or wrung dry. So every worker’s goal once they knew the score was to beat the system somehow.

My challenge was to find ways to beat the system collectively rather than individually. Most workers seek the personal way out, since it is the most obvious in their experience. Dog eat dog.

Fortunately, I had some ideas learned from conversations with Stan Weir, a longtime southern California labor organizer in the Independent Socialist League, who taught me to listen first, not preach.

Stan Weir was the model for the character Joe in Harvey Swados’ novel, Standing Fast. Stan took organizing literally: he saw the workplace as an organic structure, where the first molecule was the informal work group. These are the people you are in constant contact with, just in order to do your job.

For example, a door assembly line had about eight people directly on the line: guys like me who welded the parts together; one who “married” the inside of the door to the outside panel; an inspector who checked each piece as it went by on the conveyor belt; and several guys who loaded the finished doors into racks for forklifts to pick up and drive to waiting railcars.

Our group intersected directly or tangentially with other work groups, joining one molecule to another. We depended on the forklift drivers to bring parts and carry away assemblies, on material handlers to make the parts handy, on pipe fitters to keep the sound deadener gunk and rust prevention sprays working, and on tool makers to adjust the spot welding machines.

Offline, but within sight, were metal finishers and torch welders who repaired doors damaged in the course of assembly. Each of these tangential workers had their own informal work groups.

Stan told me that my first job was to listen to and understand the people in my informal work group, then to identify the natural leader in that group. Later I would find the leaders in other work groups and try to link them. The company organized people and groups according to their functions and linked them by foremen. Stan’s model was to see them instead as autonomous collectives linked by self-interest through their natural spokespeople. (See https://www.tempestmag.org/2022/06/a-new-era-of-labor-revolt-1966/)

Gaming the System

Many of the spot welders and press operators in our plant spontaneously found a collective way to beat the system. They did It by working harder than necessary to get the job done, then taking turns to stop working (“go on break”). If there were four loaders filling racks with finished doors, three would work at a time while the fourth took a quarter hour break, then came back and relieved the next guy.

Similarly, entire lines worked extra hard to “make production” each hour and go on break prior to the contractually agreed five-minute hourly break. Every operation had a break-even point for the hour, say 250 doors, and a production quota, say 300 doors.

Meters on the line watched with eagle eye by the foremen kept count. The extra 50 doors produced were profit. Even though it was obvious that those extra doors, our surplus value, owed nothing to anyone except we who made them, they were whisked away for company’s use any way it wished. We had zero say and Marxist economics stood naked in front of our eyeballs.(6)

Our spontaneous collective sought only to game the system rather than beat it. Management obviously knew what we were doing but went along with it because it served their interest as well: meeting their quotas.

All that changed after Japanese engineers came to America in the mid-’70s to study our system as Chrysler engineers proudly showed them through the plant. In reality the visitors were doing detailed time and motion measurements, then went home determined to eliminate all of American management’s missed opportunities to collect every calorie of workers’ energy.

Easy jobs, taking turns working, etc. were eliminated in Japan, their econocars wiping out Big Three models in the market. Detroit in turn by 1984 adopted Japanese methods, nicknamed “management by stress” by Mike Parker in his books. Auto work as a tolerable way of life disappeared.

But even before that transition, to beat the system we would have to be in a position to turn production on and off like a faucet. Instead of working harder to get a break, we would have to work slower to exert collective power and prioritize more distant goals over immediate work relief. We looked to the British shop stewards’ movement as a model for using workers’ control, but nobody came anywhere near to replicating that movement.

Plant Dynamics

Race and ethnic dynamics determined everything in the plant. Your race was determined by how some other group looked at you, usually based simply on skin color. Ethnic dynamics were independent variables.

Thus, Black workers cohered sometimes as church and neighborhood members, sometimes as street people. So did whites, family and neighborhood largely determining promotion to better jobs. Then there were self-contained European clusters, most evidently the Polish workers, some of whom could barely speak English after 20 years at Chrysler.

There were few women in the plant, so women’s issues beyond tokenism did not became political in the union hall or on the shop floor until Jane Slaughter (from the IS) hired in and started explaining blue collar feminism through the pages of the local union newspaper, where she rapidly became assistant editor.

When I arrived, union politics was defined into hard voting and service blocs. The misnamed Rank and File Slate was based in skilled trades and conspicuously racist. Skilled trades were the minority, so they depended on white production workers to control the union hall — President, VP, etc.

All were Administration Caucus (formed by Walter Reuther in the late 1940s) loyalists. In the plant, stewards and committeemen posts were controlled by the Black opposition to the Rank and File Slate. The opposition had a minority of support among white production workers. Their leaders were also total Administration Caucus loyalists.

Our strategy was to unite Black and white production workers around shop-floor issues, at the expense of the UAW brass and their sycophants, who had long since abandoned class conflict on the shop floor in favor of the “gold-plated sweatshop.” Our newsletters and flyers came to the defense of oppressed groups — Blacks or women — who were being abused.

Prior to being awarded “seniority” at 18 months, thus prior to leaflets and openly organized agitation, I joined and eventually chaired the local union Fair Employment Practices Committee. I could investigate discrimination grievances like a steward, though stewards never did.

During this period, since I also showed up at union meetings and spoke, the Rank and File Slate tried to recruit me, sending me to Black Lake, the UAW leadership resort, for training. Training amounted to following top-down leadership from the Administration Caucus and liking it.

Eventually militants had to move beyond contract proposals, shop-floor reporting, and good ideas, to contend for power in order to implement our program. Program meant not a set of declarations, but the general idea that the union was the workers. We should act for ourselves to get what we needed, not depend on the company or union bureaucrats who wanted to “represent” us as a lawyer would, shutting us up because they knew better what was good for us.(7)

Although various workers were supporters and sometimes spokespeople for our caucuses and slates, the two figureheads that defined our politics in everyone’s eyes were the tool crib attendant George Brooks and myself — one Black, one white, both independent of the existing power structure and brazen in our stances.

We re-divided the plant, replacing white vs. Black with rank and file workers vs. the company and its union handmaidens. We had slates of candidates for several union elections and convention delegations. George was elected steward and I wasn’t. In 1977, I was finally elected vice president, defeating the Rank and File Slate candidate by a solid margin, 1100 to 900, with support from the traditional Black slate. That was the beginning of the end of the Rank and File Slate and race-defined union politics at this factory.

A year later the traditional Black-led production slate won the local president spot and the traditional white-led slate started working with him. Their hope was to return to the careerist, class-collaboration union life they knew before. Racism no longer served them, so they ditched it in public. Their common enemy was us — the movement for class-struggle unionism.

Bailout and Purge

The watershed decision for class struggle vs. class collaboration came in the Spring of 1979. Should the UAW and federal government bail out Chrysler by workers accepting concessions in return for government loans to the company?

We argued that if Chrysler could not make a profit it should be nationalized under workers’ control. Workers had the skills and interest to convert it to the manufacture of useful products.

I had chosen not to run again for VP and lost in my attempt to become chairman of the shop committee, the real center of power as opposed to the union hall, so George was isolated after winning the committeeman slot for his division.

We had lost some leverage and the newly united Black and white local union leadership were unanimous in preaching that the workers “must learn to eat crow” to save the “goose that laid the golden eggs,” Chrysler.

To make sure they won the battle for concessions, the union and company collaborated to fire three IS activists in Spring 1979 — first Jane Slaughter, then Mike Parker, then me.

Jane was fingered to management by a UAW committeeman as a leader of a wildcat strike previously at Cadillac Assembly. My guess is that the committeeman relied on the UAW research department for that information. She had a week or so to go to achieve 18 months seniority, which would have protected her.

For Mike, they had to eliminate his job title and lay him off. For years afterward, the Warren Stamping Plant had to operate without an electronics specialist of its own as they avoided calling him back.

In my case, UAW Pres. Doug Fraser wrote me that the union would not win my grievance (discharge for refusing a direct order) if taken to arbitration, therefore it was withdrawing my grievance. This despite a ruling by an administrative law judge in the Michigan Employment Security Commission that I was fired without cause, “no direct order having been given and none refused,” following a formal hearing with lawyers and witnesses on both sides.

None of us won our jobs back. Organized class-struggle unionism faded away at Local 869 as some of our colleagues were co-opted as paid full-time union operatives. You could argue that I failed to build a caucus that could outlive my role in it, a democratic group rooted in its given level of collective consciousness and commitment. I prioritized forcing change in the system over spreading responsibility among our cohort.

The group was not prepared for the long defensive battle ahead. The offensive battle to win the UAW for class struggle unionism ran for eight years from 1971; the defensive battle that followed our defeat has lasted 40 years.

Building Connections Across Lines

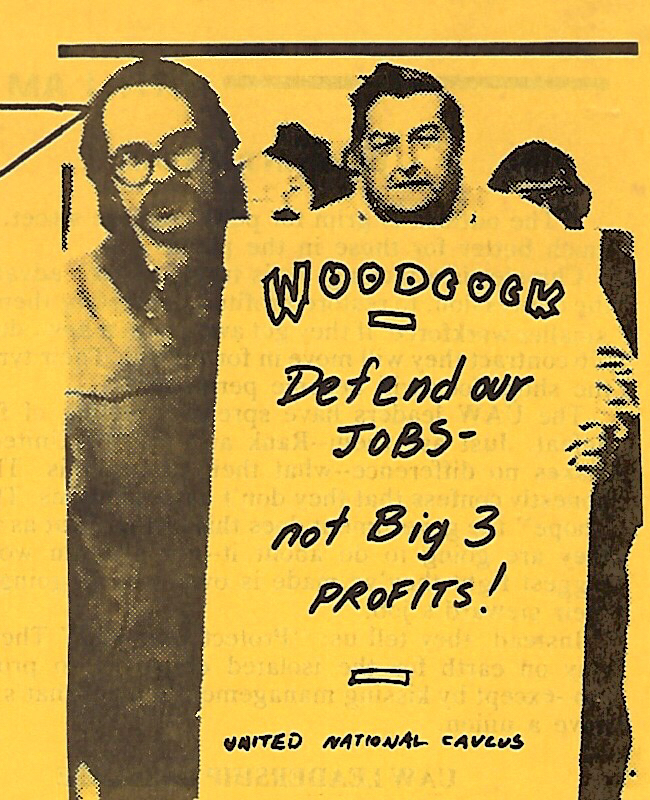

IS autoworkers collaborated across local union, company and industry lines. The epicenter of our inter-union auto work was the United National Caucus, whose citadels were the GM Tech Center where skilled workers designed cars, and Ford Local 600, the Dearborn facility that made its own steel and most everything else for cars and trucks that rolled off its assembly lines.

The UNC had organized in opposition to the Reuther Caucus in the 1960s and was well-entrenched when we arrived in the early ’70s. UNC organized picket lines and press conferences at both GM headquarters and UAW Solidarity House. We went to regional and national conferences held every year and to regional picket lines.

One evergreen issue the UNC promoted was reducing work hours under the slogans “30 Hours Work for 40 Hours Pay” and “30 and Out.” These addressed cyclical layoffs/excessive overtime, early retirement and full employment.

When the Industrial Union Division of the AFL-CIO called a March on Washington for jobs in 1975, 60,000 showed up. IS had its own banner and contingent, although our autoworkers, steelworkers and teamsters marched with contingents led by reform movements in their own industries — the UNC in my case, Concerned Truckers for a Democratic Union, the CWA United Action Caucus, the Coalition of Labor Union Women (CLUW) and others.

All these and others cohered as the ad hoc Rank and File Coalition and included unemployed people as well. The coalition had its own section of the march from the Capitol building to RFK Stadium a couple of miles away and the UNC marched as part of the coalition. The marchers were a militant group, with signs like “Fuck Ford” as well as “30 for 40.”

By far the most fun part of that day was when we at the rear of the march reached the stadium and found that it only seated 40,000 and the gates were locked. The 20,000 workers locked out quickly tore down the fences and gates and flooded the field below the podium set up for union officials and Hubert Humphrey to give speeches.

When Humphrey tried to speak, he was drowned out by boos and chants from the crowd, most of whom were probably Vietnam vets. He had long lost any credibility and took down the rest of the speakers with him. The crowd broke up to march back, thinking it had done a good day’s work by rejecting political-bureaucratic BS.

After the march, IS held a public meeting near the Capitol aimed at the Rank and File Coalition marchers. They had marched side by side from different industries, but we wanted to create a chance for them to talk together, swap literature and contact information, and think of coordinating their militancy. IS had a table to entice those who wanted to go even further.

There were no national Black organizations to ally with the way we did with CLUW. By the mid-’70s the Panther Party had lost leadership of Black liberation struggles, with nothing to replace it on the street. That militancy had moved into the factories, where Black production workers were already in the lead of rank and file movements like DRUM. There was no separation of “identity” and class politics; the Black working class in Detroit already saw its class struggle as the road to Black liberation in the streets.

IS-led union caucuses went beyond the plant level to ally with progressive single-issue movements. Example: The Free Gary Tyler campaign started in 1974 on behalf of a Black youth framed for murder by Destrehan, Louisiana cops, reached into the plants — my local called for his freedom — and into the community.

The IS youth group Red Tide participated as well. I got a Red Tide militant invited to our local union meeting by the local leadership to make the pitch for freeing Gary Tyler. The local voted in favor. But Gary spent 40 years in Angola prison, several on death row. (Gary Tyler eventually won release on a plea deal. He visited in Detroit in Fall 2022 and met with some former IS members.)

Seeds of the Future

Throughout the 1970s the IS organized conferences and network connections between rank and file caucuses, linking different industries. These planted the seeds of what later become Labor Notes. The soil they grew in, however, was not what we had planned for.

We understood that the wave of labor militancy in the ’70s was not only an extension of ’60s anti-establishment visions of a better life and resistance to everything that made life worse — war, racism, sexism. We also understood the specific economic dynamic that drove our bosses to try make their lives easier by making ours worse: the falling rate of profit.

Kim Moody, Anwar Shaikh and others analyzed the end of the postwar boom in America around 1970. During the previous 25 years, labor’s share of surplus value in highly unionized sectors had kept pace with an annual 3% rise in productivity.

Following the 1930s Great Depression and World War II, there was persistent growing demand for automobiles that kicked the can of overcapitalization down the road. By 1970 the market was saturated with commodities in the advanced Western countries and no progress was in sight toward creating new markets in the third world or the Communist countries. Nor were big wars in sight as ways to reduce overcapitalization by blowing it up.

So the corporations were on the attack. Wages and benefits hadn’t been on the chopping block in the early ’70s. Periodic wage increases were part of the corporate business model as the price of labor peace, most particularly peace on the shop floor.

We called this status quo the “gold plated sweatshop” — the union did not challenge the company with direct action on the shop floor but the company, unable to cut wages and benefits, was free to extract more surplus value in two main ways: speedup and lengthening the work day.

Speedup and its culture of treating people as cogs in the machine had already led to years of Black-led rebellions. By the time the IS arrived in Detroit, working conditions, including company racism, became the initial focus of our militancy. By the mid-’70s compulsory overtime coupled with layoffs was added to the mix and the two together triggered a sustained fightback. So we were able to make the first steps toward organizing that fightback that the UAW leaders refused to lead.

But the soil was shifting under our feet and we did not realize it. The automakers, like the American steel industry before it, moved to sustain their rate of profit by switching to a new business model: a preemptive class war on employees’ wages and benefits.(8)

They stripped the gold plate off the sweatshop. Chrysler led the charge in cahoots with the UAW leadership, betting the farm that UAW members would take money out of their pockets and give it back to the company before they would fight to win. They were right (not that UAW members were ever asked.)

The IS ranks, along with many others in the class struggle union movement of the ‘70s, were not widely enough embedded or influential with the millions of workers at risk to head off concessions. We tried and we lost.(9)

A few years into the 1980s, concessions had spread across industry. Comrade Steve Kindred, an early organizer of TDU, said at a meeting in the early ’80s “We’re going to get our teeth kicked in for a few years.” I thought he was exaggerating. On the contrary.

Lessons for Today

Looking back, I think IS made the correct choice given the alternatives available. Committed to socialism, we picked the workplace as the arena and class struggle unionism as the tool to fight for it. We had a step-by-step roadmap to get there.

When that strategy crashed as militancy ceded to the false defensiveness of concessions, one part of the IS split off to focus on propaganda and concentration in universities and some white collar sectors, where the International Socialist Organization worked with some success for decades before dissolving.

Our own strategy became moot as the U.S. economy deindustrialized and the central industrial unions like auto and steel lost their strategic power. That vehicle to a labor party and anti-capitalist socialist combat for power choked and stalled and moved over to the slow lane.

One thing stayed the same: organizing on the job, from below. The International Socialists shifted their emphasis to linking rank and file organizers across the board. Labor Notes (launched in 1979) became the institutional form this took. It provided both theory and practice for the 40-year prolonged defensive movement, and at the same time cultivated organizational techniques for going on the offensive.

DSA labor committees today are trying to decide where to invest their energies. I think it makes more sense to organize among the people you spend a third of your working days with, rather than making cold calls door to door or hanging around the fringes of other people’s organizing efforts.

It makes more sense to institutionalize whatever gains we make by direct action than to pin our hopes on the General Strike. And finally, history and our own experiences have shown conclusively that it is not enough just to win electoral majorities in either government or unions.

The Marxist idea that the working class learns the ability to govern in the course of organizing itself to win power still applies. We can’t just take over the capitalist machine.

Today’s young workers and young socialists are discovering for themselves that the rank and file strategy is the way to go and that they don’t have to wait for somebody else — in particular the traditional unions laden with bureaucracy or, like the SEIU, organizing from the top down.

The range of allies we are looking at today has broadened to reach unorganized workers, dispersed workers, unemployed and home employed workers, pink collar workers, service workers, and the public at large, as teachers’ unions have discovered.

The Quiet Quitting movement, the critique developed in the book Bullshit Jobs and the like, have nurtured a shared realm of consciousness for manual and office and home workers: the job is not what’s most important in our lives. Giving your best to the job is no longer a path to a good life at home.

The requisites of a decent life have to be applied on the job as well as off the job — such as air-conditioned trucks for UPS workers in an overheated world, or regular sleep patterns for pilots and flight attendants. Workers’ demands, union demands and public demand, converge toward campaigns for human rights.

Health is a human right. So is life — including Medicare for All, guaranteed income, socialized child care, and canceling profit to save the environment.

Notes

- “Independent” was the key word for me in joining the socialist world. The ISC owed nothing to the safe havens many American 60s radicals posed as real world supports — Cuba, Maoism, the CPs and SPs, third-world liberation. We had to make our revolution ourselves, depending on nothing but each other.

back to text - DSA faces the same problem today. It wants to be for “all good things” like a political party but can’t commit to an area where it could be decisive.

back to text - See Kim Moody for an overall picture of industrialization. https://www.tempestmag.org/2022/07/origins-of-the-rank-and-file-strategy/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=origins-of-the-rank-and-file-strategyback to text

- Key in their ability to shut down the economy of the day.

back to text - At ITT we carefully organized a sitdown strike and won in two hours.

back to text - Sometimes called “wage slavery.” I like Stephanie Coontz’ pithy comment on slavery: “Slave owners responded to the global market by combining the ruthlessly impersonal profit calculations of mass production with the cruel intimidation required to extract maximum effort on exhausting tasks while forestalling resistance by enslaved people, who vastly out outnumbered overseers and owners.” Stephanie Coontz, “American History is a Parade of Horrors — and Heroes,” Los Angeles Times Op-ed, August 14, 2022. Impersonal profit, maximum effort, thwarting resistance — life in auto factories.

back to text - In 1975 my literature in a run for local president included “30 for 40 to end unemployment; smashing racism at work, in the union and community; no support to Democrats, Republicans, Wallaceites, or Kennedy, but a labor party instead; fighting the boss at the point of production; nationalizing Chrysler if it can’t afford full employment….Equally important though were issues like the women’s restrooms and union finances….” p. 3, orkers’ Power, June 5-18, 1975.

back to text - The corresponding shift in capital strategy echoed steel captains’ failure to invest in plant in the ’60s and early ’70s to insure long run competitiveness. When questioned about this in Iron Age magazine in 1971, an industry boss famously replied “In the long run we’ll all be dead.” The big three automakers never invested to produce small, efficient cars. They have been saved from the dustbin only by SUVs and trucks.

back to text - This summary is analyzed in great detail in the closing chapters of the Rebel Rank and File: Labor Militancy and Revolt from Below During the Long 1970s, edited by Brenner, Brenner and Winslow. Verso, 2010.

back to text

January-February 2023, ATC 222

Complaints, questions, and discussion are also welcome at the author’s email dm10639@gmail.com