Against the Current, No. 220, September/October 2022

-

It's All Out in the Open

— The Editors -

Fighting for Reproductive Justice

— Shui-yin Sharon Yam -

California's Reparations Task Force

— Malik Miah -

The "Bruce's Beach"

— Malik Miah -

2022 Labor Notes Conference

— Dianne Feeley -

Bill Gates and Techno-fix Delusions

— M.V. Ramana and Cassandra Jeffery -

The Fight Over Inflation

— Suzi Weissman interviews Robert Brenner -

UAW Convention: Change in the Wind

— Dianne Feeley -

International Tribunal Verdict: "Guilty of Genocide"

— Steve Bloom -

Philippines: Continuity of Violence

— Alex de Jong -

"Can I at Least Have My Scarf?"

— Anan Ameri -

Echoes of Money in Times Past

— Daniel Johnson - Reviews

-

The War Upon Us

— Jerry Harris -

Texas: Darkness Before Dawn

— Joshua DeVries -

New Veterans, New and Old Problem

— Ronald Citkowski -

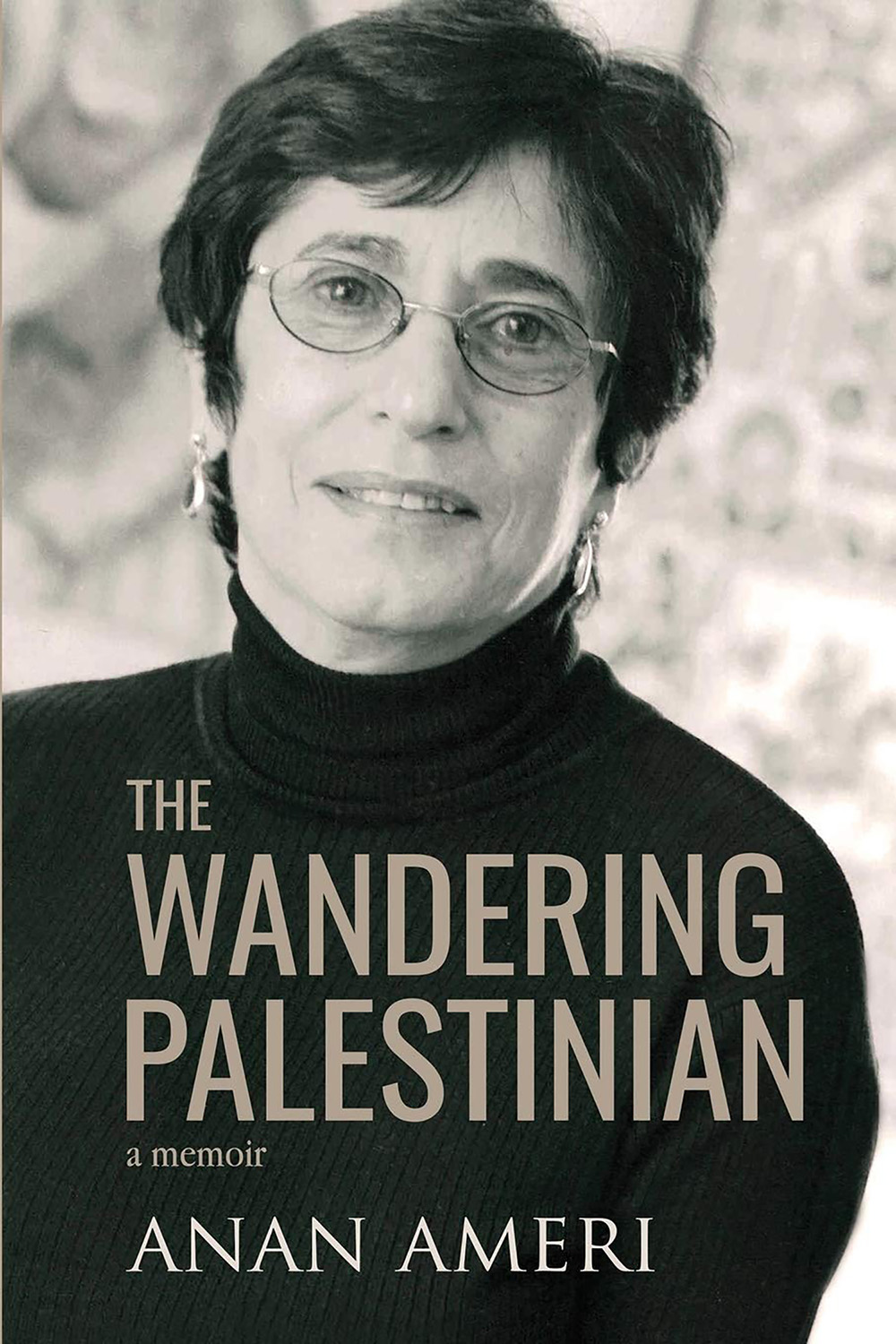

Anan Ameri, Life and Community

— Dalia Gomaa -

Joe Burns' Class Struggle Unionism

— Marian Swerdlow -

Radical Memories of Two Generations

— Paul Buhle - In Memoriam

-

Leo Frumkin, 1928-2022

— Sherry Frumkin -

Living with Political Clarity: A Tribute to Xiang Qing

— Au Loong-yu and translated by Promise Li -

Alain Krivine, 1941-2022

— John Barzman

Dalia Gomaa

The Wandering Palestinian

a memoir

by Anan Ameri

BHC Press, 2020, 242 pages, $15.95 paper.

THE WANDERING PALESTINIAN by Dr. Anan Ameri is the second volume in the author’s autobiography covering her life journey from Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria to relocating in the United States. The first, The Scent of Jasmine: Coming of Age in Jerusalem and Damascus (Interlink Publishing, 2017) is her account of growing up in the Arab world, her close family relationships and the devastating impact of the dispossession of the Palestinian people.

The Wandering Palestinian is the U.S. part of Ameri’s story, beginning in 1974, with a complex adjustment to a new life and her development as an accomplished political activist, organizer and acclaimed mentor to a new generation, particularly young Arab-American women. [Anan Ameri has contributed several articles and interviews to

While telling her personal story, Ameri interweaves her own tale with a searching journey culminating in founding the Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, which was launched in 2005 as the first of its kind devoted to Arab-American history and culture.

As we delve into the many challenges of creating this pioneering institution, Ameri’s book additionally highlights multiple issues including the diversity of Arab Americans, representations of Arabs and Muslims in American media, and issues around gender roles for Arab and Arab American women.

Before undertaking the Museum project, Ameri previously served as the founding director of the Palestine Aid Society of America, an educational and fund-raising organization with a concentration on providing material aid and vocational training for Palestinian women in Lebanese refugee camps.

The book’s first chapter opens with the classical Arabic folk tales’ phrase “Can Ya Ma Kan: Once Upon a Time.” Immediately we are hooked to know more about the love story that has brought the author to the United States. As readers follow the challenges this love story and difficult marriage encounters, they also follow the problems Ameri goes through as a newcomer to the U.S. city of Detroit.

The daughter of a Palestinian father and a Syrian mother, Ameri has been a wanderer, growing up in Jerusalem, Damascus, Amman, Cairo and Beirut. Arriving in Detroit, Ameri’s feeling of unsettlement has increased as she comes face to face with the harsh reality of poverty and segregation that has prevailed in the city (including the lack of personal security in the street, something she hadn’t experienced in earlier life).

Contrary to the conventional coming to America and the American Dream migrant story, Ameri describes her first years in Detroit in terms of loneliness, isolation, lack of independence, and depression.

Eventually, Ameri manages living in the new country, pursues her doctoral degree, and ultimately works on conceiving, organizing and funding the Arab American National Museum.

Complexity and Diversity

Readers follow Ameri’s journey on these multiple trajectories. What is outstanding about The Wandering Palestinian is its portrayal of the complexity and diversity of Arab Americans.

A sensitive as well as professional sociological observer, Ameri shares her experiences with various Arab American communities, and how different Arab American families may have different cultural traditions, what Ameri describes as “a cultural gap.”

Part and parcel of different cultural traditions among Arab American are gender, and more specifically women’s, roles. Ameri highlights the tension she encounters in her own marriage, between being an independent woman and adhering to a traditional wife role.

Inspired by the Asian American Wing Luke Museum, the Japanese American National Museum, the Tenement Museum, the Women’s Museum, and the Civil Rights Museum, Ameri’s conception of the Arab American Museum manifests the intersectionality of the Arab American identity along the lines of ethnic identity, migration, civil status, and gender roles.

Reading through her explorations of these museums, one can infer that the intricacies of Arab American identities per se manifest their Americanness — read as multiple identity categories making up the large tapestry of an American identity.

As Ameri puts it:

“Arab Americans are as diverse as the Arab world they come from… For example, some came to the U.S. as early as the 1800s and their offspring assimilated to the point of not thinking of themselves as Arab Americans. Others are recent immigrants and have a much stronger Arab identity.

“Some came from rural backgrounds with little formal education and ended up joining the American working class, while others came from cosmopolitan cities like Cairo and Baghdad, and are highly educated professionals. Some live in their own ethnic enclaves, others live in the rich suburbs.” (261-2)

In telling her story, Ameri contributes and expands the continuously growing Arab American female voices telling their stories from their own perspectives, such as Diana Abu-Jaber (Fencing with the King, 2022), Mohja Kahf (Hagar Poems, 2017) Randa Jarrar (Him, Me, Muhammad Ali: Stories, 2016), and Joanna Kadi (Thinking Class: Sketches from a Cultural Worker, 1999) to name only a few authors and recent works.

September-October 2022, ATC 220