Against the Current, No. 219, July/August 2022

-

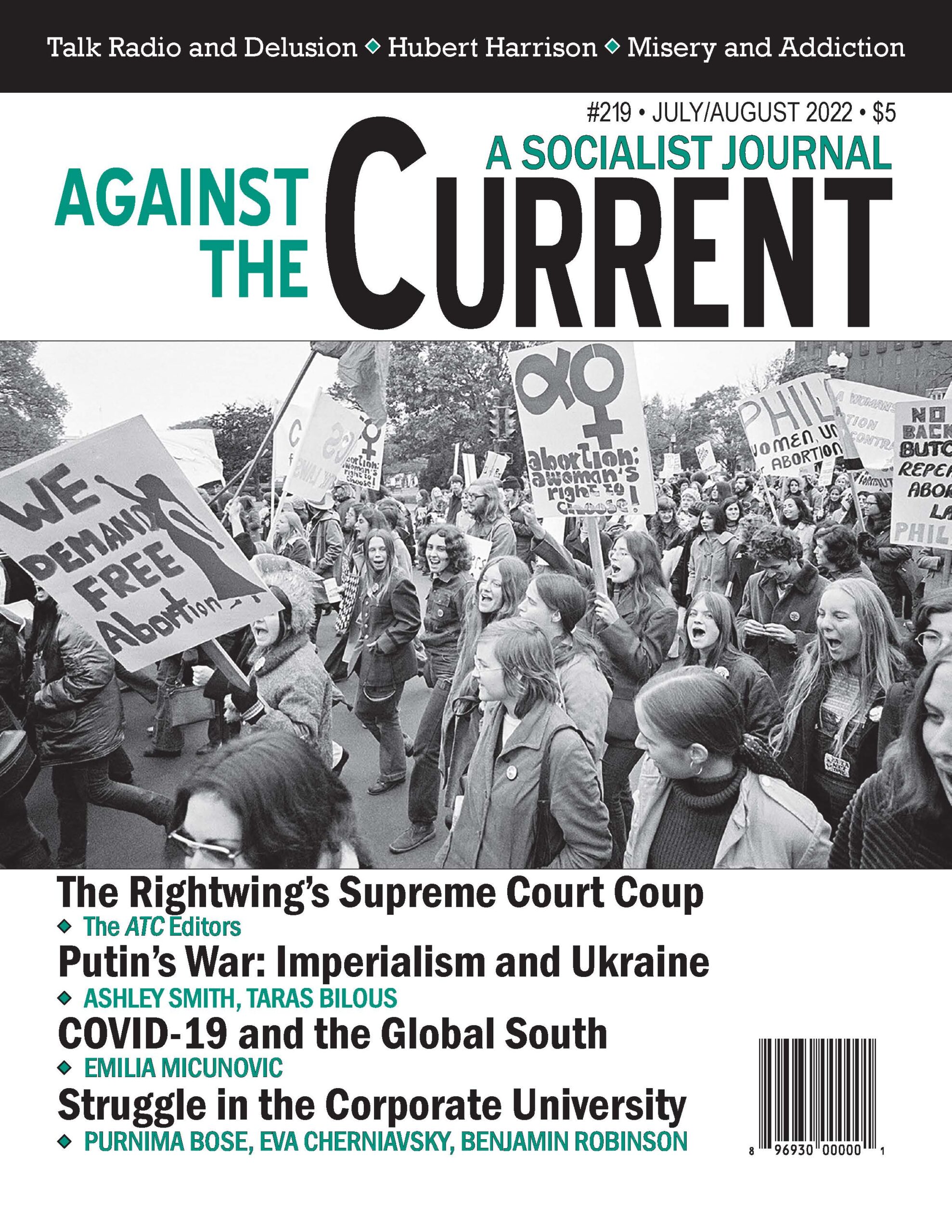

The Rightwing's Supreme Court Coup

— The Editors -

Assange, Donziger and the DNC Media

— Cliff Conner -

A Letter from California's Death Row

— Kevin Cooper -

COVID & the Global South: the Nigerian Case

— Emilia Micunovic -

Ukrainian Leftist Speaks

— an interview with Taras Bilous -

After Russia's Invasion of Ukraine

— Ashley Smith -

The Murder of Shireen Abu-Akleh

— David Finkel - The Case of Derrick Jordan

- Struggle in the University

-

The Competence Curse

— Purnima Bose -

Faculty Governance in Academia

— Eva Cherniavsky -

Renewal of Shared Governance?

— Benjamin Robinson - Revolutionary Experience

-

An Introduction, A Conclusion

— The Editors -

To the Working Class, 1969-1980

— Dan La Botz -

Field Work

— Sam Friedman - Reviews

-

Migration Politics and Criminalization

— Cynthia Wright -

Disability Studies from South to North

— Owólabi Aboyade (William Copeland) -

Mass Misery, Mass Addiction

— Dave Hazzan -

A Giant Rescued from Oblivion

— John Woodford -

Three Mothers Who Shaped a Nation

— Malik Miah -

The High Price of Delusion

— Guy Miller - In Memoriam

-

Oscar Paskal, 1920-2022

— Nancy Brigham

Owólabi Aboyade (William Copeland)

Disability in Africa:

Inclusion, Care, and the Ethics of Humanity

Toyin Falola and Nic Hamel, editors

Boydell & Brewer: Cambridge University Press, 2021,

452 pages, $155.25 hardcover.

“Some people think that it is only white people who can come up with new theories, and they’re wrong!” he said and all the ministers chorused back Yeees!!!!!” — Ngūgī wa thiong’o, Wizard of the Crow (2006)

IN THESE VIRUS days, more people than ever are familiar with or concerned about physical debilitation. Still, for those who think of themselves as regularly “healthy” or able-bodied, the lived experiences of those with impairments other than Corona or long-Covid are invisible at best and quite frequently, filled with exclusion, stereotypes and oppression.

Likewise, many of what Trump calls “shithole countries” of the Global South have existed under the burden of centuries of foreign interventions and the denigration of indigenous ways of being in favor of the more successful, violent and monotheistic conquering stories of those who occupy and steal from us.

At the outset of this review, I’ll talk more about my subjectivity and how I read Disability in Africa.

I am a New Afrikan, a descendent of Africans stolen from the Continent. We see the political fight for sovereignty from the U.S. Empire as more fundamental than equality within it. I am a disability justice care organizer from Detroit, the Blackest city in the United States. I have lived with kidney disease for 30+ years, oftentimes presenting and being treated as able bodied.

I am a member of Detroit’s African-centered community and have studied overarching trends on the continent, but I am not a specialist in the politics and histories of specific African nations. A large part of my intellectual work is distinguishing what is different in the Black/New Afrikan experiences of disability from mainstream dialogues on disability, and even the prominent U.S. experiences of disability justice.

I worked in the environmental justice field for 15 years. Here I saw the complexities of embracing a disabled identity, specifically in my Detroit communities. We would cite statistics of cancers and asthma, but were unable to craft an approach to uplift the leadership or even experiences of people with chronic illness.

When I stepped away due to my own health crisis in 2017, my experience mirrored the experiences of women leaders profiled in Chapter 15 of Disability in Africa — our focus on institutional and policy change blocked us from meeting the needs of the most vulnerable and physically debilitated. This trend is increased when funders and the goals of “scaling up” enter the picture.

Any Good from Crippled Africans?

In the Biblical Book of John, when hearing of the prophetic word of Jesus/Yeshua, Nathanael asks “Can there any good thing come out of Nazereth?” (John 1:46)

Echoing that verse, philosopher Darien Pollock asks in parallel: “Can anything good come from the streets? Can anything good come from a place where the majority of society forgets to look? Can anything good come from a place where the resources are limited but the hope and creativity is not?”

We might ask, similarly, “Can anything good come from crippled Africans?”

Disability in Africa works on many levels:

It includes some keen pictures of African organizing, caregiving, creativity and post-war survival — although unfortunately you have to dig around to ?nd these.

It challenges disability policy in Africa and shows how some important aspects don’t come from Africa but are imported from NGOs and global thought leaders.

It includes stereotypes of African indigeneity and tradition, and some authors posit medicalization and modern policy tactics as the only way forward for the continent.

This academic collection others a sweeping scan of disability issues around the continent of Africa. It is a book that aspires towards the field of disability studies, so its focus is theorizing disability in conversation with those who study.

The academic praxis differs from the organizing, healing or survival praxes, in the assumptions of who the reader is and what they will be doing with the text. There can be overlap, yet the purpose of establishing and validating African disability studies is fundamentally different from the purpose of compiling a book that will help African disabled peoples organize, heal, or create collective power.

Toward an African Conceptualization

There’s an ideological war being fought on the pages of this book. Like wars between international powers, sometimes it’s fought by proxy.

Some authors in this collection are writing and fighting for the modernizing force of Western knowledge including medicine and its associated concepts of rights. Some of these authors view African traditions and ancient ways as the root of the problem for disabled Africans, and argue that the solution is found by addressing “valid issues” and frameworks backed by “scientific research.”

Other authors are encouraging that Africans mine deep into African traditions and systems to find ways of conceiving collective well-being. These practices and systems of knowing can thus be used to build public health, social institutions and practices of communal well-being.

I won’t be able to summarize all of the texts in this academic anthology, but will highlight some that may be of interest to Against the Current readers.

Chapters 3, 4 and 6 are probably the best examples of pushing discourse towards an African conceptualization of disability. Chapter Three, “An African Ethics of Social-Well Being,” explores how disability relates to African theories of sociality and morality; and Six, “Disability and Cultural Meaning Making in Africa,” how Africans with and without disabilities make sense of experiences of impairment.

These chapters ask how African systems of thought can be the basis of practices ranging from public health and legal institutions to support groups. They shine a light on the call for inclusion — not merely to mimic the unemployment rate of able-bodied Africans in the post-colonial states, but to provide experiences of public belonging and capability that are too often denied people with disabilities.

Chapter 4, “Rethinking African Disability Studies” pushes towards a materialist or Marxist analysis of disability, asking what are the primary means of production in various African societies and the resources they collectively create, then looking concretely at how people with various impairments are treated in those societies as a result of the roles available or denied them.

This is an important text — looking at a variety of societies in Africa — because many other texts in this anthology focus on single countries whose policies are measured by the fulfillment of modern middle-class deliverables such as employment and education: Ghana, South Africa, Kenya, a few others.

Chapter 16, “Disability Policy, Movement Activism, and the Nonenforcement of a Disability Act,” is one of my favorite chapters. It is a foundation read to the entire book.

The book’s editors conclude that the United Nations’ “Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)” has failed to improve the lives of those with disabilities in the global south generally.” (407)

Chapter 16 investigates these failures as it astutely looks at the pressures in Ghana to pass laws coming from the UN and other international bodies, but then shows the mechanisms and motivations for not enforcing, resourcing, or implementing them in the Ghanaian context.

Ambiguous “Signs of Progress”

The chapter points to an irony evident elsewhere in the anthology: more than a few chapters point to the passage of national laws as “signs of progress” in the disability rights struggle. Policy has become a location for international virtue signaling as well as a mechanism to develop a nation’s internal NGO infrastructure.

Chapters 8 and 10 look at representations of disabled people in African literature. Chapter 8, “Paradoxical Dramaturgies,” looks at the depictions of disability in the works of the Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka in his 1971 play Madmen and Specialists (inspired by his imprisonment in that country’s civil war — ed.).

That work has a chorus who are described as the “vulgar disabled.” They laugh about raffling off their body parts. Their response to the overarching oppression of postcolonial Africa they are in is not to “fight for justice,” but to laugh and try to manipulate the situation as best they can. I felt echoes of the hip hop spirit and its relationship to the violences of urban poverty systems. The overarching method of this chapter is to use cultural contexts and rituals to look at depictions of disability, providing a more nuanced understanding of what Soyinka is conveying than simply comparing them to expectations coming from disability rights, liberation, or activisms.

Chapter 10, “Masculinity, Disability, and Empire in J.M. Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians,” is an analysis of African masculinity, looking at a literary depiction of a colonizer in Africa. This is unique because the magistrate in this novel (Waiting for the Barbarians, 1980) sees himself as a “respectful” person and tries to distinguish himself from the brutality of previous colonial administrators (dominant men).

This chapter is relevant because this book does not spend much time connecting Europeans’ current and historic imperialism to the life experiences of disabled Africans. The source of ableism is too often implied or stated to be the African states and societies themselves.

A further reading of this chapter will compare the position of the magistrate as attempting a new and improved colonial dominance over the “barbarians” to today’s neo-colonial masters wielding NGOs, policy demands and human rights frameworks in order to “enlighten” the African continent with regards to disability or other issues.

From Africa Back to Detroit

Lastly I highlight chapter 15, “So that the Stew Reaches Everybody,” which analyzes strategies that women leaders take in Ghana’s disability movements. This chapter speaks most directly to the methods and challenges of disability community organizing.

Interestingly, the author observes that “women leaders focused more on internal matters than on advocacy for structural or social change (as do men leaders).” It would be valuable to revisit. We see this so often in Detroit: Organizations that focus on policy change can very easily become detached from the work of improving the lives of the poorest and most marginalized.

I enjoyed the glimpses of postcolonial interrogation in the book, where the situation of disabled Africans — their organizations, societies, and states — were placed in historic and economic context and not reduced to a single issue of disability oppression.

I enjoyed the depictions of how disabled Africans think with regards to survival, caregiving, organizing and leadership. I even enjoyed the contradictions between the optimism and recognition provided by human rights frameworks, declarations of inclusion, and the challenges faced on the ground by Africans with disabilities.

Can anything good come from bringing disability studies to Africans?

Next steps would be include engaging with Africana/Black Studies, an academic discipline that is critical of the hegemony of the academy; and at its best, studies and teaches to advance the liberation of Black students and communities.

It would be amazing also to see what will come from African engagement with disability justice — our movement’s anti-capitalist practices of inclusion and rebellion forged from the blood, sweat, tears and thoughts of disabled, sick, Mad, crip folks fighting racism, sexism, heterosexism, ableism and other forms of hegemony within the North American settler states.

We still live in a world in which there is an idealized body, mind, family and society and that fictional standard is “white” “well-off” and “healthy.” Disability studies in Africa has the potential to organize and advocate for increasing material resources, care, and support for disabled Africans. In addition to providing clear analyses on exclusion of disabled folk within African nations, it can point towards global contexts of exploitation and structural domination. African disability studies can show a way towards attaining the dignity of collective care without putting Western principles, policies, and organizations on pedestals.

I encourage readers to take in multiple texts within this book. (Given its price, get your library to get it!) Listen to the multiplicities of voices and perspectives; prepare yourself to challenge mainstream notions of “the handicapped” as well as popular notions in the West about inclusion and disability discourse.

You’ll learn about African cultural contexts and ?nd perspectives here that you can use to support disabled people wherever you live.

July-August 2022, ATC 219

Thank u for this challenging , thoughtful contribution to folks studying theory, philosophy and practice related to disabilities studies . You challenge us all to see the world thru African eyes and history and thus consistently show another world is possible and ask the question – what does it mean to be human in the ecology of history and the planet!