Against the Current, No. 216, January-February 2022

-

COP26: Success Not an Option

— Daniel Tanuro -

Afghan Women: Always Resisting Empire

— Helena Zeweri and Wazhmah Osman -

Entangled Rivalry: the United States and China

— Peter Solenberger -

On Global Solidarity

— Karl Marx - #MeToo in China

-

How Electric Utilities Thwart Climate Action: Politics & Power

— Isha Bhasin, M. V. Ramana & Sara Nelson -

Ending Michigan's Inhumane Policy

— Efrén Paredes, Jr. -

Oupa Lehulere, Renowned South African Marxist

— James Kilgore -

Reproductive Justice Under the Gun

— Dianne Feeley - Save Julian Assange!

- The Horror of Oxford

- Racial Justice

-

Why Critical Race Theory Is Important

— Malik Miah -

Texas in Myth and History

— Dick J. Reavis -

A City's History and Racial Capitalism

— David Helps -

Reduction to Oppression

— David McCarthy -

Protesting the Protest Novel: Richard Wright's The Man Who Lived Underground

— Alan Wald - Revolutionary Tradition

-

The '60s Left Turns to Industry

— The Editors -

My Life as a Union Activist

— Rob Bartlett -

Working 33 Years in an Auto Plant

— Wendy Thompson - Reviews

-

Michael Ratner, Legal Warrior

— Matthew Clark -

The Turkish State Today

— Daniel Johnson

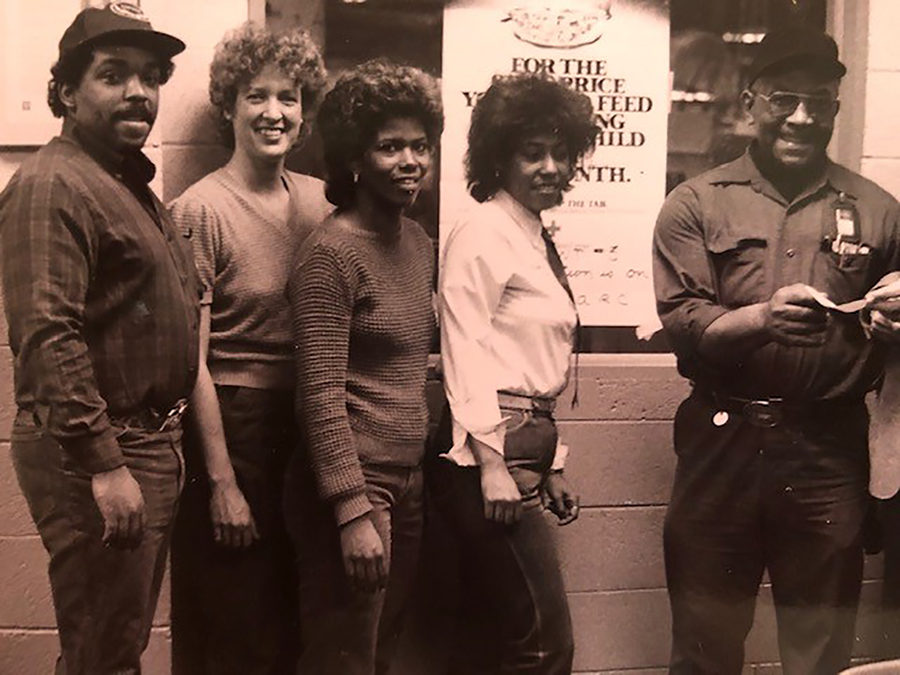

Wendy Thompson

IN 1960 MY family took a trip to Jackson, Mississippi. Shortly after, my father, a Methodist minister, was arrested there for attempting to integrate churches. I became a committed political activist in the civil rights movement at the age of 12.

Years later, when I arrived in Detroit to industrialize and live in the Black community, I felt immediately comfortable. I was fortunate to have grown up on the border of the large Black community in Evanston, Illinois, near Chicago, and to have gone to an integrated elementary school. My brother and sisters and I met and played with Black kids in the alley — the border — even before I went to school.

I chose to go to college in California because of the vibrant student movement. I saw that the University of Southern California was in the Black community and was attracted to that — not knowing it was an almost totally white student body of Southern California’s ruling class. I would have left had it not been for an Urban Semester of independent study where I got involved with a local high school in a struggle against a racist principal.

As a French major, I participated in “junior year abroad” in France ’68-’69. I wasn’t in Paris but rather the university in Aix-en-Provence near Marseille. There I became active in the student movement at its height. Strikers spoke at mass meetings on campus. We handed out leaflets at factories that workers enthusiastically took.

I became a socialist there so I returned to Los Angeles looking for socialists. I ran into the International Socialists (IS) and immediately joined. Because of my experience in France, I was open to get a job in industry. The IS had a list of target industries: mining, steel, auto, telephone and trucking. I had planned on teaching French in inner city schools but was concerned about the relevance of French for them and with having to deal with discipline.

Industrializing Perspectives

My IS partner became an autoworker in Los Angeles. As I got to know his fellow workers, the idea of doing this kind of work appealed to me. This was just before the 1970 GM strike, when I organized a student strike support committee. We also participated in Teamster picket lines at the beginning of what became Teamsters for a Democratic Union.

We visited IS members who were already in Detroit and were impressed by a city where most workers seemed to have beautiful single-family homes. As autoworkers in Detroit, we would be in the center of the industry. We saw the film “Finally Got the News” about the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM). This was the clincher for me.

DRUM was a step beyond the Black Panthers because it focused on the power of workers rather than just the community. The power workers had could protect them from assassination. The massive Dodge Main plant that was DRUM’s home base had wildcats against racist foremen, speedup and other working conditions.

In line with our perspective many IS members moved to Detroit to become autoworkers. My partner and I arrived in May, 1971.

Auto comrades were in an auto “fraction” where we would think out campaigns and plan recruitment. Where we had members in specific plants, that sub-fraction would meet to discuss problems and how to carry out the work. We would be joined by other members not working there. I remember we had ISers in three plants with about five members each and five other plants with one or two members.

The auto fraction would meet as a whole and then report to our branch and national organization. We studied UAW history and knew they had traded away fighting for better working conditions in exchange for higher wages and benefits. We felt the UAW had a left-wing tradition from the 1930s to build on despite the destruction created by McCarthyism. We wanted to rebuild the union from the shop floor.

Our original idea was to build “struggle groups” that did not interact with the bureaucratic union. These would organize around shop-floor struggles and working conditions.

However, we soon dropped that concept for a rank-and-file caucus that used union meetings and structures to put forward our solutions to everyday problems. Our goal was to build a national caucus.

We knew a handful of socialists who had been longtime UAW activists. They stood in opposition to the Administration Caucus, the caucus Walter Reuther built when he became president of the UAW and built an authoritarian machine. By the ’50s he called all who opposed him “communists” and tried to exclude them.

Getting Our Feet Wet

It took a while to find jobs. We would hear rumors of hiring and line up with many others at factory gates at 5 am. I started hearing “no ladies’ jobs,” so on my applications I put four years of factory experience instead of college.

Since we weren’t immediately successful in getting auto jobs, we also tried to get telephone jobs, another IS priority. In the meantime, I worked in a hospital. I enjoyed working with women in a union organizing campaign, but the pay as a nurse’s aide or ward clerk was terrible.

Finally, in March ’72, we applied at a complex of multiple plants on both sides of a city street. Called Chevy Gear and Axle, it had a workforce of 8000. It was the only GM plant where most workers were Black and had a militant history. I got hired but my now husband did not. Turns out they were looking for women. Chevy Gear was an all-male plant but because of the women’s movement, GM was afraid of lawsuits. I was one of the first four women (two white and two Black) to walk into my plant in the complex since World War II!

More women were hired. White women were few and far between, but all the women became close as a group because of our situation. All the white men told me I shouldn’t be there, I should be at home. The Black men said “welcome.”

The scariest thing about the plant was the noise. Conveyors with large metal parts would travel overhead as we walked down the aisles protected by metal mesh. I spent my first week as a janitor on the day shift. On day one there was a knife fight and I had to clean up the blood. Then I was transferred to afternoons and went to work on the assembly line.

As more women came in, the men who’d been happy to see us at first changed their tune. They got upset because they saw us as taking all the “good” jobs. Yet as more women came in, we were given harder jobs. But it took a while for us to get jobs like hi-lo driver, inspector or to break into skilled trades.

Immediately after the 90-day probation, some of the women started going to union meetings. I was told that everyone had been “packing” guns. But that ended when women started attending the meetings. The local leadership formed a women’s committee quickly and invited us to the UAW Educational Center at Black Lake.

As more women were hired in, second-shift after-work parties were organized. Another IS woman and I would go to the parties together but most whites didn’t attend. Partly as a result, Black workers saw us as different, calling us “friendly.”

At first, the white foremen would come flirt with me, but that all changed when I organized a small group to put out a leaflet about our work conditions. We worked 12 hours, seven days and people were tired of it. We had two walkouts, and no one was penalized.

After being identified as a troublemaker, I was put on one of the hardest jobs that no one person should have to do. Of course, I couldn’t quite lift the axle above my shoulders onto a hook, so they landed on the floor. I was quickly taken off the job and later a hoist was developed.

Before long I got fired. They investigated my references to working at a factory, which wasn’t International Sonics but the office of the International Socialists in New York City. Despite my lie, my case had merit because it was a clear example of being fired for union activity. Management stupidly put it in the second step minutes that they had investigated me — and only me — because I handed out leaflets that were “bad for union-management relations.” I was out for nine months.

After my discharge, I distributed my newsletter “Shifting Gears” plant-wide and gained support. In my newsletter I called for a meeting and this led to a rank-and-file group, the Justice Committee. Our base of about 20 — who would attend union meetings — came from the work of one white militant committeeperson and a Black worker who told me: “I know exactly what you are trying to do, and I agree with you completely.”

Three Black workers from a DRUM affiliate, Chevy Revolutionary Union Movement (CRUM), joined with us as well. But DRUM was hostile to IS comrades because they saw us as Trotskyists while they had a Stalinist perspective. However, DRUM as an organization was already losing its strength.

The Justice Committee put out a monthly newsletter discussing our working conditions. We tried to raise the question of racism in each issue. We made what the IS fraction considered later to be a mistake when we declared ourselves in opposition to the Administration Caucus.

As a local caucus, we could not really challenge a national machine and it put us unnecessarily under the gun. The Administration Caucus came into the local and organized an attack on us. We were called into an Executive Board meeting over something we had written in a newsletter and this discouraged participation.

However, we won a significant victory at a union meeting. The UAW Convention had changed terms of office in the Constitution from two to three years. Creating longer terms was part of the bureaucratization process. But to soften the blow, the change allowed Shop Committee terms to remain at two years with a vote of the local membership. We won the vote and were the only local we knew of that was able to pull this off.

Being “Revolutionary” In the Plant

It was a sign of the times that at one of our Justice Committee meetings, person after person announced they considered themselves revolutionary. Since the IS perspective was to recruit the most militant workers, at one point I invited a lot of workers to come to an IS recruitment meeting.

Some came, but not the key people. The message they took back was that I was crazy out of my mind! I had invited too broadly, but it was significant that the most militant workers didn’t come.

An IS member not working in the plant would sell our paper, Workers’ Power, at the front gates. The goal was to help win workers over to revolutionary consciousness by connecting workers’ struggles to broader issues. I often found that workers most interested in our paper would not be interested in being activists.

Besides our local caucus, the IS was also involved in a national caucus, the United National Caucus, along with some of the older socialist leaders we’d met. In fact, one of them wrote my discharge case.

I feel I won my case with back pay because of rank-and-file support. But people warned me that GM would be out to get me. Management had outed me as a socialist in the grievance procedure, but given the local’s history that got me points with the head of the retirees’ chapter.

I was fired again for five months in ’74 but returned in ’75 — again, with back pay. Shortly thereafter, I was elected Committeeperson, representing 250 people. Other IS members at various Chrysler locals were elected committeepersons and one was elected Vice President of his Local.

One way to build a campaign on the shop floor is to write a group grievance. Although the Shop Chair said there is no such thing, I established that as a procedure. I would write group health and safety grievances and get everyone to sign. I spent all my time out on the floor talking to people.

The plant manager (who later became the owner after the plant was sold in 1994) sent a young African-American plant superintendent out on the floor and invited workers to become supervisors. At one point I accused him of being sent in to fire me. He said no, his goal was to get me defeated!

Since he had the power to grant all my grievances, he worked to convince the membership that he was responsible for the gains we won. He also worked with the Shop Chair to put out on the floor that a majority Black plant should not have a white committeeperson and convinced my alternate to run against me.

The sub-fraction discussed the difficulty I was in and decided I should put a leaflet out saying why the membership should vote for me even though I was white. The leaflet backfired and played a major role in my defeat. It made fraction members feel that as whites coming from outside the local they were unable to successfully advise me.

What I learned from that experience was that if there is a rumor on the floor, it is a bad idea to put that rumor in writing because you are doing the opposition’s work. (The hotshot superintendent years later sought me out to say how much he admired me and asked me out to dinner. I said no despite his charisma. Vindication, yes!)

Another factor in my defeat could have been because I functioned as a “revolutionary” committeeperson, an idea IS later rejected. When I finished my rank-and-file work, I would engage in revolutionary work on elected time. People felt they did not elect me for my politics, so this was wrong. They had a point. I was trying to recruit key workers to “the revolution.”

Two broader campaigns comrades throughout industry conducted during this period were support for Gary Tyler, an African-American teenager in Destrehan, Louisiana falsely charged with murder (I sold Gary Tyler t-shirts) and support work for Zimbabwe; we sent clothes to the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) during the liberation struggle, when Mugabe was still progressive.

[Gary Tyler was sentenced to death at age 16 after a frameup murder conviction. The sentenced was commuted to life in prison after an international outcry. After 41 years in prison, he was released in April, 2016. —ed.]

In 1975, I took my vacation and went to Portugal to check out the revolution that had overthrown a fascist government. I went to a small industrial town, Marinha Grande in the north where workers controlled every factory. I toured their plants and found that they could hold meetings whenever they wanted and won all their demands. The mayor’s house was taken over and made into a childcare center.

I was so excited about their socialist experiment that I put out a leaflet about it in my plant. I now regard this as a mistake because it launched so much discussion I couldn’t possibly explain my point of view.

The Recession and Its Aftermath

Most auto comrades worked in Chrysler plants and were able to recruit Black workers during this period. We had a youth group that used salt-and-pepper teams to de-escalate racial incidents. A Black collective in Los Angeles joined IS and moved to Detroit to get jobs but no one could find a job. Those were wonderful times, but they didn’t last!

The recessions of the late 1970s brought a big change. We thought workers would rise up and form unemployed committees both nationally and locally. Although we participated in a city-wide unemployed committee sponsored by a UAW local, it was unable to accomplish anything.

However, our Justice Committee was able to get a motion for a laid-off workers’ committee passed in my local. These Laid-Off Committee meetings were extremely successful for the length of the layoff, and once back to work led to a reactivated women’s committee. There was also a militant, activist Women’s Council at UAW Region 1 that I participated in. It was very unusual for the Administration Caucus to allow such an activist orientation at this high a level.

New caucuses and leaders in the local came forward who sounded militant and the Justice Committee did not last. I remember one, “The Heat Is On,” who were younger and had a militant appearance; they did not allow whites to be members. Their leader was very autocratic and anti-communist.

The IS concluded we had misjudged the political situation. The post-recession period was a vastly different for several reasons.

The Administration Caucus was able to increase their power as they accepted the concessions the companies demanded. They, along with the company, said givebacks were necessary for the corporations to continue and workers to have jobs. Although they claimed we could win back these losses as times got better, that of course never happened. Workers were told we were lucky to have a job.

New caucuses and leaders came forward who sounded militant. Because they lacked an ideology of social justice, they were easily won over to the Administration Caucus’ perspectives. Once in office they might continue to make militant statements, but they demobilized members and justified additional concessions. They proved to be anti-democratic and conservative.

My plant’s work had been producing axles for the rear-wheel drive Chevette. But GM had moved to front-wheel drive production, and our work was no longer relevant. Both the impact of the recession and the advent of new technology made autoworkers more frightened about their future. Workers no longer felt confident that wildcats and other militant action could prevent management from layoffs or plant closures.

In this new period, different perspectives arose within the IS and there were several splits. Additionally, comrades were laid off, some for five years or more. As a result, our auto fraction shrank. For those of us able to maintain our UAW membership, several were hired in other plants. I, fortunately, was able to stay at my plant. Still others moved to different cities and took different jobs. Many remained labor activists but left the IS.

Given that we had to adjust our perspectives, we decided it would be important to try to build an institution that would be politically independent and connect shop-floor activity to building a national labor movement. It could bring together workers in different industries so that we could learn from each other.

In launching Labor Notes in 1979, the IS clearly rejected the model that many socialist groups had of maintaining the broad groups they built tightly under their control. Originally staffed by IS members, Labor Notes was to be a project where workers would feel they were in a comfortable milieu but also a pond where socialists could swim. It has since published books and organized conferences and trainings.

The United National Caucus of the ’70s did not last either. A successful national group continued for a while in the skilled trades called the Independent Skilled Trades Council. We continued building national networks like Locals Opposed to Concessions (LOC) to explain the need to organize against concessions at UAW Conventions and during contract negotiations.

We struggled against the union accepting “joint” labor-management programs and opposed the practice of locals outbidding each other in offering concessions and therefore allowing the company to whipsaw one group of UAW members against another. We also campaigned to win one member, one vote for our top UAW officers rather than the delegate system that allowed the Administration Caucus to control our union.

New Directions

In the mid-’80s, as the IS merged with other socialist groups to form Solidarity, some of us were elected delegates to a UAW convention where we ran into New Directions, a movement from Region 5 that was running Jerry Tucker for Regional Director against the Administration Caucus candidate.

New Directions had successfully organized opposition to lean production systems by using work-to-rule campaigns. We joined them immediately. In fact, Victor Reuther came out of retirement to join with New Directions and oppose the Administration Caucus strategy of cooperating with the corporations.

Tucker’s election was stolen but he appealed to the Labor Board, which ordered a new election that he won. Yet he only had a year left of the three-year term. The Administration Caucus mobilized its full strength against New Directions candidates and defeated Tucker next time around, preventing New Directions from spreading to other regions. They couldn’t tolerate a situation where there was a clear alternative to accepting concessions!

Yet one victory New Directions won was forcing the Administration Caucus to provide the actual contract language — and not just a summary they prepared — to the membership before ratification.

I was Shop Chair at the time and the first to put out the actual local contract language. Of course, since the language is not written for working people to understand, there was a lot of misunderstanding about what the contract meant. However, Skilled Trades (a separate division in the local) voted it down twice and production once. We held meetings and were able to go back to the table and win improvements!

Over this decade, my shop floor work continued. Although I was elected Education Director, then Committeeperson again, then Shop Committee, then Chairperson of Shop Committee, then Local President, I couldn’t build a rank-and-file group. But I continued to put out and distribute my newsletter and build election slates.

Given that the Administration Caucus collaborated with the companies for joint programs — along with the funding and staff appointments that went with them — some of my allies were later convinced that supporting local Administration Caucus candidates would get them brownie points.

Once I aligned with New Directions, the slander against me became so intense it led to my “sit down and shut up” period. Although I was actively organizing on the shop floor and continuing my newsletter, I could not play a role at union meetings.

However, in my district we had lunchtime meetings of group leaders. We organized a group to go visit a top manager’s office. I held break time grievance procedure classes.

Women as Sex Objects

I never got any support from the UAW leadership on the question of sexually oriented pictures in the workplace. While I was Shop Chair I had to go into a General Foreman’s office for grievance procedure meetings I was met with a girlie calendar on the wall. I requested it be taken down; the foreman refused.

I brought a male nude calendar in with me and laid it down on the table next to me, saying nothing. The foreman was clearly taken aback and embarrassed, but still refused to take the calendar down. I reported the incident to upper management, the International UAW and wrote a grievance. Nothing changed.

During the Senate hearings on Clarence Thomas’ nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court, I was extremely upset about the way Anita Hill was treated. I didn’t hold union office, but I had to do something to fight back in the plant. I wanted to have two 5×7-foot girlie posters — ones I was forced to pass every day — taken down.

I approached the two workers responsible for them and asked that they be removed. Although they had been supporters of mine, they both angrily refused. The skilled tradesman complained to his fellow workers, who organized as a group to retaliate against me.

Eventually, with the cooperation of a mutual coworker, I was able to convince the second man to take down the sexist poster. But he did it grudgingly.

I put out a short leaflet about the sexist and inappropriate posters and expressed my support for Anita Hill. A Black woman who was my political enemy took the occasion to spread pictures of naked men all over the ladies room. I decided not to engage her about it. I had never been as unpopular as I was at that moment!

Later I ran for Committeeperson in the district I had represented previously. I was beaten by a white male who had run in the past but only gained a handful of votes because he rarely came to work. The day before the election, my opponent put a large cardboard stand-up woman on my job. I ignored it, but the word went around the plant in two minutes that I had taken it out back and stepped all over it like a crazy woman. I feel my taking on the male privilege of putting up sexist posters played a role in my defeat that time around. Today hopefully there is a greater consciousness about offensive and sexist images at work.

Restructuring in the ’90s

By the ‘90s, GM demanded that parts workers within the GM system be paid less than assembly workers. The UAW had rejected this demand in negotiations, so GM’s response was to sell off the parts plants.

Then our plant, along with four other GM plants, was sold. We were taken by surprise because axles were considered a core component and all were made within the Big Three. In my newsletter I accused GM of selling so they could lower our wages. With others I organized a picket line down at the GM Headquarters to protest the sale.

The Administration Caucus did nothing to protest the sale and claimed they would protect our wages in subsequent contract negotiations. Most workers moved to other GM plants, but I decided to stay. I put out a copy of the sale Memorandum so we would understand our rights.

The big question was health care. Who was more likely to lose it in retirement through a company going bankrupt? Ironically, it was GM that went bankrupt during the 2008-09 recession while AAM (American Axle & Mfg.) maintained its health care!

A younger workforce came in. They liked my newsletter while the new owner hated it. They say he demanded “Shifting Gears” be put on his desk every month.

I organized a group grievance against outsourcing, which my corrupt committeeman refused to accept. Immediately afterward, I was fired for a third time and was out for 18 months. Paying to maintain my health care and for what my teenage son needed as he was going to college was stressful as my case went all the way up the steps to final arbitration.

If I lost my case, I would have lost everything including much of my pension. Until the end management offered me money if I would voluntarily quit or transfer to GM. But I won when five witnesses showed up to testify on my behalf; I was reinstated and received $100,000 in back pay and benefits.

Later, I was elected Local President. However, the most powerful position, the Shop Chair, was a corrupt and bitter enemy who told management not to let me into the plant. I still put out my monthly newsletter, standing at the gates. As president I was one of 10 in national negotiations where two-tier wages was the main issue.

Once it was clear the UAW negotiator was for two-tier as a way of “saving” our jobs, I was the only one willing to oppose it. Another comrade on the shop floor and I worked together to get the contract voted down at our local, but it still passed nationally.

Since we could not turn the slates into an ongoing caucus, our alternative strategy was to mobilize for local classes, committees and special meetings such as celebrations during Black History month. One positive thing I accomplished was to get the entire leadership of 50 elected and appointed people to sign a leaflet that circulated in the plant condemning a racist noose incident.

Despite the difficulties and setbacks, I have to say I enjoyed being an autoworker and working with a majority Black workforce. I disliked the elitism I encountered in college; in the plant I wasn’t around people who thought they were better than others. While I was a “strange person” to many, there were other “strange people,” so I felt I belonged.

As times got more difficult politically, it was stressful. But it was not dull! I was continually able to engage in organizing projects because the class struggle was there every day. Of course, I benefited from good wages and benefits.

I appreciate my pension and health care in retirement and realize how lucky I am to have had basically one job over the course of my work life. That is not the general experience of working people today.

It would be nice to see some victories after so many defeats. And I’m glad that Labor Notes, Teamsters for a Democratic Union and DSA are here to play a role to make a better future possible.

Within the UAW, more than a dozen key members of the Administration Caucus stand convicted of corruption. As a result, the International UAW agreed to a membership referendum on whether to institute one member, one vote for the top officers or stick with the current rotten system.

We won the referendum! This was an issue opposional UAW caucuses have been fighting for over many years. It’s great to see this victory! Hopefully, this will be the first step toward rebuilding a more democratic union. And I’m glad that Labor Notes, Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) and the Democratic Socialists of America are here with us to play a role in making a better future possible.

January-February 2022, ATC 216

Thanks for writing this. So few people with similar experiences tell the world. We need to know.

This is a most thoughtful and self reflective piece. And this is from someone who admired you immensely.

Wow Wendy! Just amazed how dedicated you have been the good cause of workers” rights. And I had not realized before just how entrenched sexism has been inside these auto plants. Proud you have stood up tor women’s right to work with dignity in their workplace. Glad you are able to enjoy a well deserved retirement! Your cousin Phil