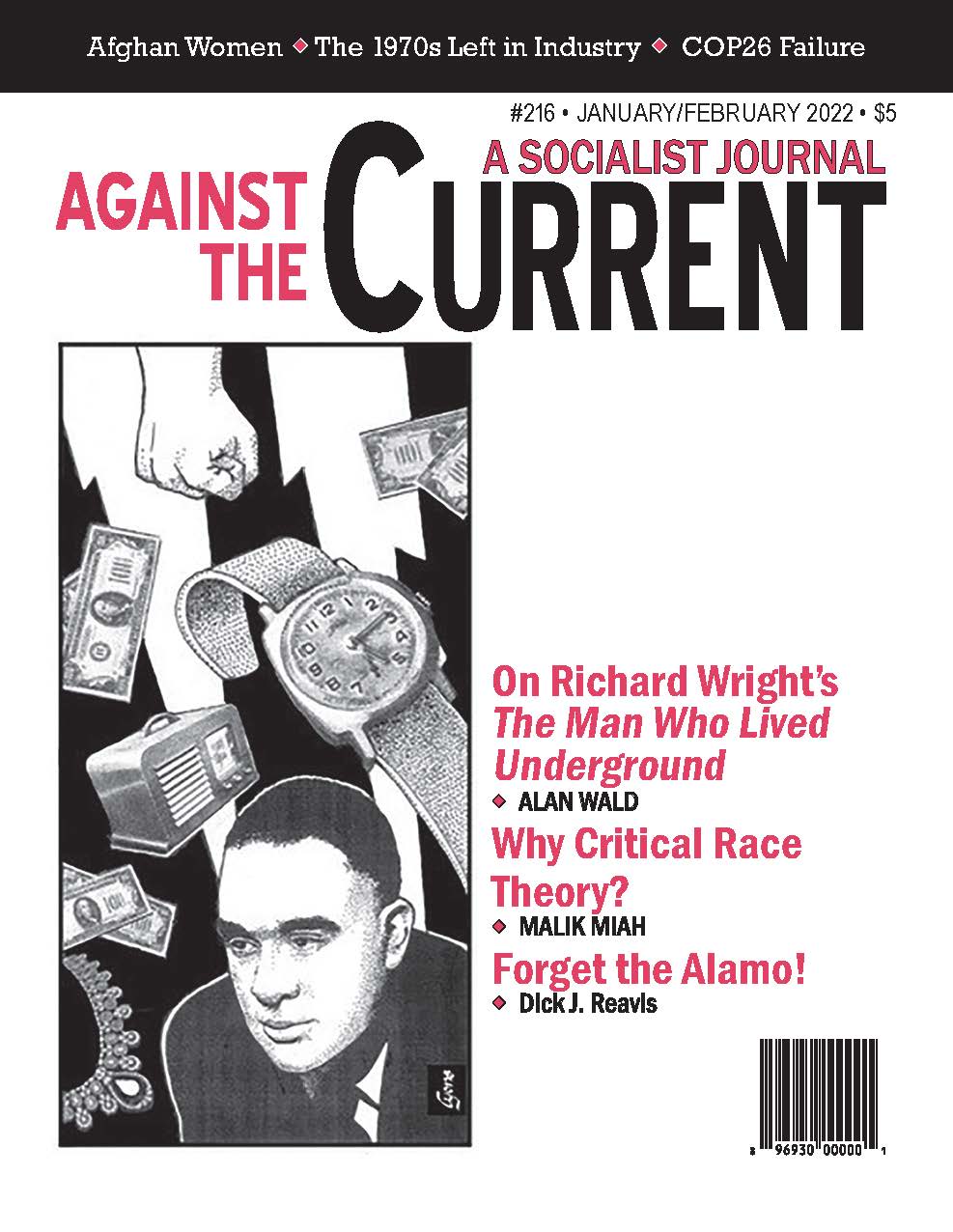

Against the Current, No. 216, January-February 2022

-

COP26: Success Not an Option

— Daniel Tanuro -

Afghan Women: Always Resisting Empire

— Helena Zeweri and Wazhmah Osman -

Entangled Rivalry: the United States and China

— Peter Solenberger -

On Global Solidarity

— Karl Marx - #MeToo in China

-

How Electric Utilities Thwart Climate Action: Politics & Power

— Isha Bhasin, M. V. Ramana & Sara Nelson -

Ending Michigan's Inhumane Policy

— Efrén Paredes, Jr. -

Oupa Lehulere, Renowned South African Marxist

— James Kilgore -

Reproductive Justice Under the Gun

— Dianne Feeley - Save Julian Assange!

- The Horror of Oxford

- Racial Justice

-

Why Critical Race Theory Is Important

— Malik Miah -

Texas in Myth and History

— Dick J. Reavis -

A City's History and Racial Capitalism

— David Helps -

Reduction to Oppression

— David McCarthy -

Protesting the Protest Novel: Richard Wright's The Man Who Lived Underground

— Alan Wald - Revolutionary Tradition

-

The '60s Left Turns to Industry

— The Editors -

My Life as a Union Activist

— Rob Bartlett -

Working 33 Years in an Auto Plant

— Wendy Thompson - Reviews

-

Michael Ratner, Legal Warrior

— Matthew Clark -

The Turkish State Today

— Daniel Johnson

Peter Solenberger

THE ENTANGLED RIVALRY of the United States and China partly repeats old patterns. States and empires have been rising and falling, cooperating and clashing for 5000 years, capitalist ones since the early 17th century, and imperialist ones since the late 19th century.

As China gains on the United States, tensions are rising, trade wars are breaking out, and shooting wars threaten. A familiar pattern.

The rivalry presents new elements too. It developed as part of a process of capitalist restoration across Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, China and Southeast Asia.

By the early 1990s the United States was the sole superpower, and China a relatively backward capitalist country. Thirty years later the Chinese economy is approaching the size of the U.S. economy; China and the United States are imperialist rivals.

How did China do this? Why didn’t the United States block it? What’s the situation now? How might it develop? What interests do workers have in the conflict? What should socialists advocate? This article begins to explore these questions.

China in the 20th Century

The subject of this article is the U.S.-China conflict, not China itself, so the account in this section is necessarily highly schematic.

Against the Current has covered China over the years. Here are five ATC articles and reviews I found particularly useful: “The Realities of China Today” by Martin Hart-Landsberg (ATC 137, 2008), “Resistance in China Today” by Au Loong Yu and Bai Ruixue (ATC 161, 2012), “China: Rise and Emergent Crisis” by Jase Short (ATC 175, 2015), “China: Workers Rising?” by Jane Slaughter (ATC 178, 2015), and “Hong Kong: An Uprising and Its Fate” by Promise Li (ATC 210, 2021). For additional background and global analysis see the article “China: A New Imperialism Emerges” by Pierre Rousset.

From the mid-19th century through the mid-20th century China was a semicolony, formally independent but dominated by the “great powers” of Europe, the United States and Japan. China won full independence and national unification through a series of revolutions and wars from 1911 through 1949. It split from the Soviet Union, its erstwhile patron, in 1961 and set its own course.

China succeeded in part because it is an immense country in land area, natural resources, and population. But these alone would not have been enough for it to make the breakthrough it has. The additional factor is its revolutionary history.

China was never socialist, but the government that came to power through its 1949 revolution expropriated the capitalists and landowners and prevented the U.S. and European imperialists from reestablishing their domination. The government, with Mao Zedong at its head, was authoritarian, often cruel, and often stupid, but it transformed the country economically and socially and laid the basis for China’s subsequent growth and development.

In the latter 1980s the Soviet government under Mikhail Gobachev experimented with perestroika (market restructuring) and glasnost (political openness) to try to get past the stagnation of the economy and society. The effort failed. The Soviet Union collapsed and the government bureaucracy restored capitalism, turning state property into private property through “shock therapy.”

The process went too far and threatened to turn Russia into an impoverished vassal of European and U.S. capital. The Russian ruling class, mostly the old bureaucracy and its friends, turned to Vladimir Putin and the security apparatus to restore an authoritarian state.

The Chinese bureaucracy, led by Deng Xiaoping, saw perestroika as necessary but rejected glasnost, as it brutally demonstrated with its repression of the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989.

It managed the process of capitalist restoration more smoothly than the Soviet bureaucracy did, essentially offering rising living standards in exchange for acceptance of its rule. Despite massively increased inequality, disappearance of workers’ job security, particularly in the private sector, and dispossession of peasants, China grew rapidly. Wages and salaries rose, and workers and the professional and managerial middle class gained more freedom in their work and personal lives, although not in political life.

Growth and Contradictions

The International Monetary Fund estimates the 2021 nominal (exchange rate) gross domestic product (GDP) of China to be $16.64 trillion and that of the U.S. to be $22.94 trillion. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic China was closing the gap, growing at an annual rate of five to seven percent to the U.S. rate of two to three percent. China’s population is more than four times greater, so its per capita GDP is just $11,819, compared to $69,375 for the United States.

If China were to continue growing as it has in the past, it would overtake the U.S. economy and become the alpha imperialist power. That certainly is the intention of Chinese President Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). But China has many contradictions which may prevent this. Here are some:

An insufficient resource base (and misuse of some of what it has). It scours the world for energy and raw materials, but this makes it vulnerable to their being cut off.

An aging population, out of the labor force but needing to be supported. This, combined with the draining of the peasantry from the countryside, limits its ability to keep growing on a labor-intensive basis.

Technology that’s highly advanced in some areas but inadequate in others. Production still relies too much on foreign firms and imported designs, machinery and components.

Impressive results achieved through extensive growth — doing more of what it has done before — but market and bureaucratic blindness misdirects investment. For example, bank loans to developers to build buildings that aren’t needed has produced a real estate bubble with the potential to become a financial crisis unless the government intervenes massively.

Unregulated growth has destroyed China’s environment, poisoning land, water and air and jeopardizing its (and the world’s) future.

The party-state-directed capitalism-without-democracy model makes the regime vulnerable to demands for democratic rights by workers and the urban middle class, whether or not living standards continue to rise.

China’s capitalists may not accept government tutelage much longer, which could turn China toward a more conventional neoliberal capitalist model.

An intense but somewhat hidden class struggle, which could escalate and open up new possibilities.

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed the strengths and limitations of the Chinese system. The government could impose lockdowns and quickly bring down the rates of infection and death, but its vaccines use older technology and aren’t as effective as those made by more advanced countries, and its top-down, all-or-nothing methods impose too much unnecessary hardship.

U.S. versus China

The U.S. and Chinese economies are entangled by trade and investment. In 2018, according to Chinese government figures, China exported $478.4 billion in goods to and imported $155.1 billion in goods from the United States, making them each other’s leading trade partner.

U.S. corporations make immense profits from trade with and investment in China. This tempers what they will allow the government to do, but the U.S. ruling class sees the threat China poses and is concerned.

Barack Obama tried to shift the focus of U.S. foreign policy from the Middle East to Asia to counter China’s growing power. His “pivot to Asia” included diplomatic approaches to Pacific rim countries, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), military buildup in the Pacific, and a trillion dollar program to “modernize” U.S. nuclear weapons, forcing China into an arms race it can’t afford, as Ronald Reagan did the Soviet Union in the 1980s.

Donald Trump scrapped diplomacy and the TPP to pursue a unilateral confrontation with China. He continued the military buildup and imposed tariffs and trade restrictions, most dramatically barring Huawei, a Chinese electronics company, from doing business with U.S. firms. Joe Biden has doubled down on confronting China, while returning to Obama’s multilateralism.

There is much the United States could do, if it really tried to contain China. U.S. per capita GDP is six times that of China, reflecting its higher overall labor productivity. This gives it potentially a much larger surplus to develop its technology, its productive forces, and its military.

It could, hypothetically, adopt an industrial policy to shift production from China back to the United States or to countries with which it doesn’t compete. The U.S. ruling class of course is typically allergic to anything labeled “industrial policy,” but to a certain extent this shift has happened as a result of market forces.

Wages of Chinese workers have risen enough so that China is no longer a lowest-wage supplier. Production of clothing and shoes has shifted to Vietnam, Bangladesh and elsewhere in Asia, and to Mexico, Central America and elsewhere in Latin America.

The industrial policy could include quotas to limit imports from China, tariffs to equalize prices, and subsidies to consumers for higher prices. It could include directing U.S. companies to produce domestically what they used to import from China.

Import substitution wouldn’t be easy. For example, Apple designs and markets smartphones and computers, but these are assembled in China in factories run by the Taiwanese company Foxconn. Apple couldn’t immediately move production elsewhere.

For another example, China processes most of the lithium and other metals needed for batteries. The United States might obtain supplies of the raw metal, but it couldn’t immediately process them.

The United States could, hypothetically, blockade China and prevent delivery of energy, raw materials, components, and machinery. But China could retaliate, cutting off shipments to the United States and bringing world trade to a standstill.

The last time the United States tried to strangle an imperialist rival was in the leadup to World War II. Washington wanted Japan to get out of Manchuria and China, and tried to cut off its supply of oil, gasoline, iron and steel, and other commodities. Japan responded with the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, hoping to knock out the U.S. fleet and force it to back off.

Both China and the United States have nuclear weapons. A miscalculation now could mean a much bigger catastrophe than World War II.

The Rest of the World

Washington could not contain China on its own, since other countries could provide China with anything the United States tried to deny it.

During the Cold War, Washington built alliances which it could now try to activate against China. These include the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which links the U.S., Canada and Europe; various treaties with Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, most recently the AUKUS security pact announced in September 2021; and the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty.

Germany, Britain, Japan and other U.S. allies have an entangled rivalry with China similar to that of the United States. They also have entangled rivalries with the United States and with each other. Getting the U.S.-led imperialist alliance to act against China would be essential to U.S. containment efforts, but it wouldn’t be easy.

China has its own alliances, most importantly with Russia. The two countries just extended the 2001 Sino-Russian Treaty of Friendship for another five years. Through it Russia gets capital and consumer goods, and China gets energy and military technology. Iran and Venezuela supply China with oil in exchange for investment and manufactured goods.

China has developed economic relationships with many countries around the world. Its “Belt and Road Initiative,” adopted in 2013, is an attempt to to extend these. Borrowing imagery from the ancient Silk Road, “belt” refers to land transportation to connect China with the rest of Asia, Europe and Africa, and “road” refers to sea routes extending to Oceana and Latin America.

In 2018, again by Chinese government figures, China exported $1.188 trillion in goods to Asia, $104.9 billion to Africa, $474.6 billion to Europe, $148.8 billion to Latin America, $513.5 billion to the United States and Canada, and $53.1 billion to Australia and New Zealand.

In 2018 China imported $1.193 trillion in goods from Asia, $99.2 billion from Africa, $379.4 billion from Europe, $158.4 billion from Latin America, $183.7 billion from the United States and Canada, and $116.9 billion from Australia and New Zealand.

In 2018 China’s stock of foreign direct investment was $1.982 trillion. $1.276 trillion was in Asia, $46.1 billion in Africa, $112.8 billion in Europe, $406.8 billion in Latin America, $75.5 billion in the United States, $12.5 billion in Canada and $44.1 billion in Australia and New Zealand.

These economic ties would be sufficient for China’s economic development, if the United States and the other imperialist countries left it alone. But that’s a big if.

Imperialist Outcomes

If the future of the U.S.-China rivalry is determined solely by inter-imperialist relations, the result could be unfortunate for the world. No one has a crystal ball to see what will happen, but there are some possible scenarios to stimulate thought.

China’s contradictions and the maturing of its economy might slow its growth to the rate of the United States and the other advanced capitalist countries. This is essentially what happened with Japan, which gained on the U.S. through the 1980s and then fell back.

Or China might continue to grow at its current rate and catch up with the United States, recreating the bipolar world of the Cold War but with two capitalist superpowers vying for supremacy.

That’s a scary prospect, since the last period of unchecked inter-imperialist rivalry led to two world wars. If the United States and its allies block China’s access to energy, raw materials, markets, and sites for investment, China has to choose between backing down or chancing a limited war. The history of the United States and Japan 80 years ago doesn’t inspire confidence.

Possibly, the United States and its allies might disentangle their economies from China and force it back on itself, slowing China’s growth and containing the inter-imperialist rivalry. But this would require a degree of planning that capitalist countries generally show only in wartime.

Or conceivably, the current imperialist alliances could break down, and new ones form. However fraught the present situation looks, if the working class doesn’t intervene the future is likely to be worse, since capitalist expansion and environmental collapse will intensify the inter-imperialist conflict.

Working-class Internationalism

Republican and Democratic politicians and the corporate media denounce China for being authoritarian and violating human rights and for unfair trade practices. Much of what they say about authoritarianism and human rights is true, but their criticisms reek of hypocrisy.

The United States itself is no model of democracy. An 18th century federal system designed to limit government, first-past-the-post elections, compounded today by racist gerrymandering and voter suppression, unlimited campaign spending, corporate media, and the two-party system mean that the government does only what a consensus of the ruling class wants.

The U.S. Constitution supposedly guarantees civil and human rights, but the rights of Black, Latinx, Indigenous and other people of color, of immigrants, of women, and of LGBTQ+ people remain constantly under attack. Racist policing, the militarized border, and white vigilanteism spread terror. This country locks up far more of its population than China (or any other nation) does.

To say that China engages in unfair trade practices begs the question: By what standard? What’s unfair is the inequality within and between nations. In a fair world, the Chinese economy would be four times the size of the U.S. economy, so that the two countries could have equal living standards.

Workers don’t have an interest in maintaining inequality domestically or internationally. We would all live more happily in a world in which everyone had peace, security, food, water, housing, a strong public health system, medical care, education, recreational opportunities, a stable and clean environment, meaningful work, personal and political freedom, and leisure to enjoy them.

Workers get drawn into “America first” and similar nonsense when they’re persuaded that life is a zero-sum game in which they have to deny a good life to others in order to have one of their own. They can be won away from this if they come to see that fighting together against their mutual oppressors is more effective than fighting each other and letting their oppressors win.

Socialists can promote this learning process by helping to build struggles and raising a class perspective, an internationalist perspective, within them.

To do this we need to consistently oppose U.S. militarism and war, including the Obama-Trump-Biden buildup against China. We need to consistently oppose protectionism. Workers in Michigan can’t gain at the expense of workers in Ohio. The employers will just whipsaw us. Similarly, workers in the United States can’t gain at the expense of workers in China.

This doesn’t mean covering up the crimes of the Chinese capitalists and government. Internationalism requires solidarity with workers and the oppressed in other countries, not apologies for their rulers. We just have to remember that living in the United States, our main enemy is at home.

January-February 2022, ATC 216