Against the Current, No. 215, November/December 2021

-

The Rising Price of Insanity

— The Editors -

Reproductive Justice on the Line

— Dianne Feeley -

Teenagers Are Children, Not "Bad Seed"

— an interview with Deborah LaBelle -

Blocking an Ecocidal Pipeline

— an interview with Rebecca Kemble -

The Ecosocialist Imperative

— Solidarity Ecosocialist Working Group - Hitting the Bricks for "Striketober"

-

The Assault on Rashida Tlaib

— David Finkel -

Nicaragua, as Elections Approach

— Margaret Randall -

Crime Scene at the U.S.-Mexico Border

— Malik Miah - Revolutionary Tradition

-

The '60s Left Turns to Industry

— The Editors -

The SWP's 1970s Turn to Industry

— Bill Breihan -

Organizing in HERE, 1979-1991

— Warren Mar - Reviews

-

Preserving Voices and Legacies: Jazz Oral Histories

— Cliff Conner -

On COVID's Death Toll

— David Finkel -

Reflections on Party Lines, Party Lives, American Tragedy

— Paula Rabinowitz -

Reclaiming the Narrative: Immigrant Workers and Precarity

— Leila Kawar -

Envisioning a World to Win

— Matthew Garrett -

Sharing and Surveilling

— Peter Solenberger -

A Labor Warrior Enabled

— Giselle Gerolami

Bill Breihan

THE SOCIALIST WORKERS Party (SWP) was organized in 1938 as a democratic centralist cadre organization. Standards and expectations of membership were high.

Coming out of the 1950s witch hunt, party membership –– which had peaked at 2,000 during the post-war strike wave –– was down to only 400. Once concentrated in the industrial trade unions, few party members still worked there, the political conditions and prospects for recruitment considered so unpromising.

Growing in the late 1960s during a period of worldwide youth radicalization –– and in response to the Cuban Revolution and civil rights and antiwar movements –– the SWP had by the early 1970s a substantial presence in the public sector unions, particularly the teachers. Though nearly a quarter of party members were in unions, the only organized party groupings in industry were a few small local concentrations –– the building trades in San Francisco, rail in Chicago.

In the early ’70s an insurgent movement developed in the Chicago-Gary district of the United Steelworkers led by Ed Sadlowski, president of the 10,000-member local union at the South Chicago works of U. S. Steel. There were then 128,000 union members in the district, the union’s largest.

When Sadlowski lost his bid for District Director in 1973 due to vote rigging, the Labor Department, responding to a union challenge, ordered a new election, which he won handily 2-1. As the half-million mill workers covered by the Basic Steel Agreement had neither the right to vote on contracts nor the right to strike when the contract expired, Sadlowski backed formation of a union Right-to-Strike Committee, in which the handful of SWP members active in the union, including me, got involved.

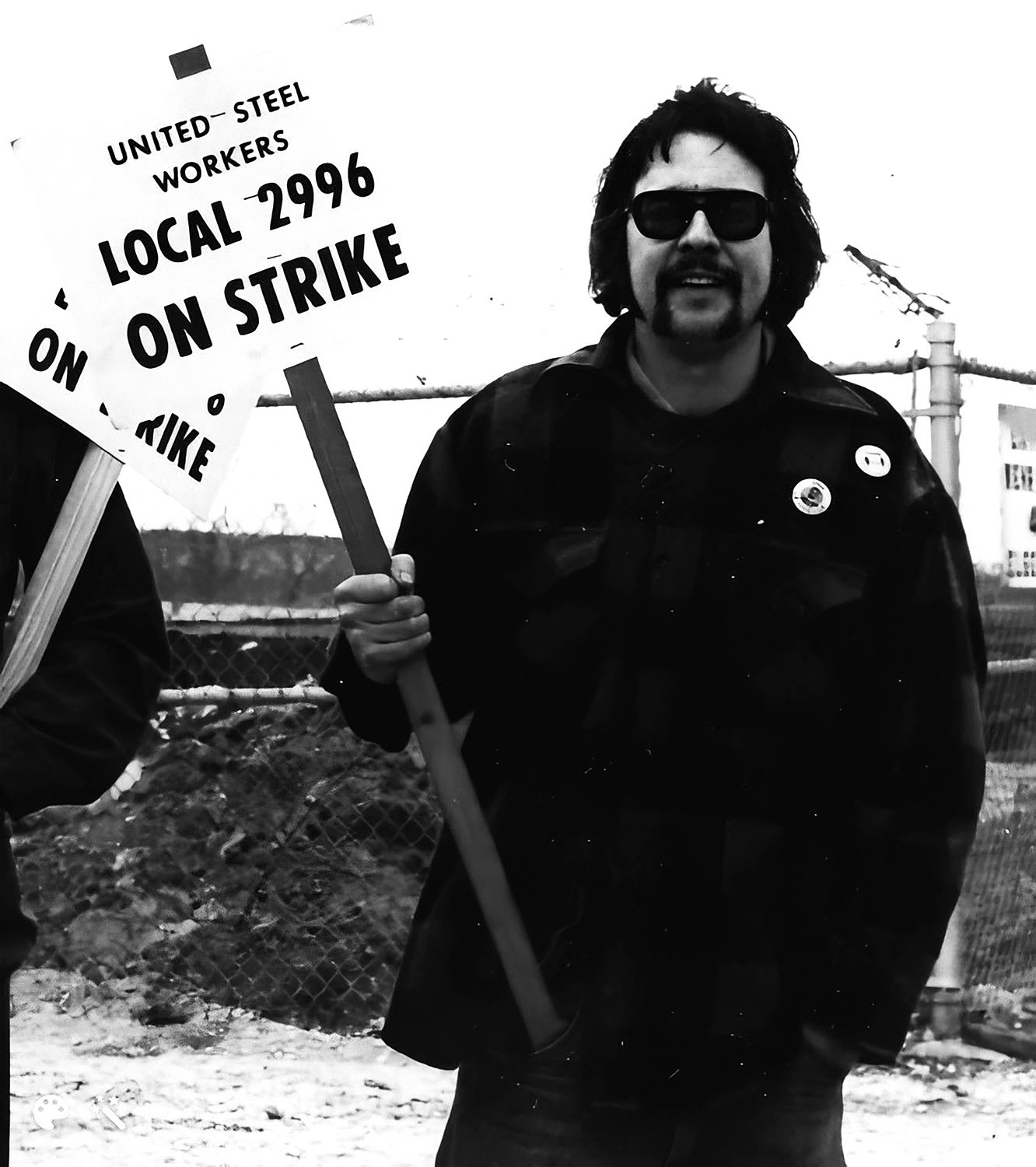

Steelworkers Fightback Work

I had worked in steel mills –– including one where my father worked –– off and on since 1968, the year I graduated high school. A portion of that time I was in college, where I learned about socialism, passing through Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), then the Young Socialist Alliance (YSA), youth group of the SWP. When I helped establish a branch of the SWP in St. Louis in 1973, I was working in a mill.

One leading SWP steelworker activist, Alice Peurala, had worked at Sadlowski’s South Chicago mill for 20 years. She recruited to the SWP a co-worker who had also worked in the mill for years. A couple of SWP members also got hired there and soon we had a presence.

When Sadlowski launched the militant, union-wide formation, Steelworkers Fightback in 1975, he followed it with a campaign for International President. The small, but growing, number of SWP members in the union threw themselves into the campaign.

SWP union groups were called fractions. These were our party work groups. My first, informal national steel fraction meeting was in Chicago on the occasion of a Right-to-Strike conference in 1974. In 1976 during the height of the Sadlowski campaign for President I took a week vacation to campaign at the Gary mills.

Steelworkers Fightback candidates were contending for local and district office across the country. I learned then that the SWP’s presence in the union had grown to a dozen, a number actively engaged in the campaign. These members had not, for the most part, been directed by the party to enter the industry. They were more often than not rebel youth who wanted get into the thick of things.

There were a few older party stalwarts who acted as advisors. In addition to Alice Peurala, who went on to become the first woman elected president of a basic steel local, I remember Jack Sheppard, who had been a union leader at American Bridge in Los Angeles since the ’40s, veteran of some of the big battles of the postwar strike wave. Jack came into Chicago to work on the campaign.

I can recall being with Jack and Alice at a campaign meeting at the Steelworkers Fightback office and then at Sadlowski’s house, later at the home of labor journalist Staughton Lynd and at the union’s annual memorial at the site of the 1937 Republic Steel massacre, where ten strikers were murdered by police. Sadlowksi lost that election, but three Fightback candidates were elected, then and in a subsequent election, to the International Executive Board –– three District Directors, including the left progressive Jim Balanoff, who took Sadlowski’s former District Director job.

The SWP would hold a big conference every summer in Ohio –– one year a convention, the next an educational conference. In the ’70s about 1500 would attend. I remember a steelworker fraction meeting there in August 1977 after the Steelworkers election. Several from the party leadership sat in on the meeting. The room was packed.

After listening to the discussion, SWP National Secretary Jack Barnes got up and explained how this was the most important work the party was doing, how the steel fraction was leading. That did it. For the next year it was all “steel, steel, steel” –– the hot topic in the organization as dozens more entered the industry.

Turn to Industry

A few months later in December there was a SWP National Committee plenum. These national leadership meetings would take place every few months. The report coming out of the plenum had current SWP membership at 1780. In addition, there were several hundred members of the party youth group, the YSA. A steelworker friend of mine on the National Committee told me later it was reported there were 2300 members total, including the youth.

That December NC meeting discussed the Political Committee’s proposal to make a party “turn to industry.” There was a follow-up plenum in February 1978 that finalized the decision and brought it to the membership, not for approval but for implementation.

The process of industrialization was already well underway by that time in steel. The SWP’s weekly newspaper, The Militant, had expanded its coverage of the industry and union and hundreds of copies were being sold at mill gates –– especially of the issue detailing the recent Basic Steel contract with its Experimental Negotiating Agreement (ENA) no-ratification-vote-no-strike provisions.

I attended a national steel fraction meeting less than a year later and was surprised to learn we now had, as reported, “over 200 in steel.” At that time we had some 120 party members in the Chicago-Gary area. Thirty-nine were now working in the mills. We had more than a dozen in rail there as well. And this was just the beginning.

For a full year, the focus had been almost exclusively on steel, but in many cities there wasn’t much of a steel industry. We had about 300 party members in metro New York-New Jersey organized in eight branches, but there were relatively few steel jobs there.

There was, however, hiring going on at the Brooklyn Navy Yard and at a Ford assembly plant in nearby New Jersey. In short order, in an organized effort of impressive scale, we got nearly 50 hired at Ford and about the same number at the navy yard, building and refitting ships. It must have been something when they all got off probation and found themselves stepping on each other’s toes trying to “talk socialism” and sell subs to the newspaper.

Never mind, the Ford plant soon closed. The navy yard had few of the unions now targeted by the leadership. A couple years later there were only a handful still working there.

In California where the SWP had several hundred members, the steelworkers had relatively few union locals. The autoworkers (UAW) and machinists (IAM) organized the aerospace industry. Autoworkers also had several auto assembly plants organized and the IAM represented mechanics at the big airline hubs. Dozens of SWP members got jobs in these industries and unions.

Living in Milwaukee by now, I was working at a big mining equipment plant organized by the steelworkers and my wife — also a party member –– at one of the General Motors plants. There were soon seven in her local union party fraction, five of them women. They worked to revitalize the local union Women’s Committee, organizing buses of unionists to various state capitols to mobilize for ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment.

By 1980 the party’s national auto fraction approached the size of the steel fraction. At one point there were, I was told, 180 in auto. The machinist fraction may have been about 150 at its height a year later. With these changes in colonization targets, the party’s presence in the steel industry declined significantly. In fact there was considerable fluctuation in the size of the national union fractions over the next several years.

National union fraction meetings were held every summer at the Ohio party gathering but also periodically in between. My wife says she can remember attending auto fractions in St. Louis, Detroit and New York. Most of my national steel fractions were held in Chicago.

The members of the fractions usually elected their leaders. In most cases what that meant was whichever member of the party National Committee –– or much smaller Political Committee — was assigned to work in a particular industry, that person would be chosen to lead the fraction. When Malik Miah was serving as National Chairperson of the SWP, he was also working at United Airlines and, as I recall, headed the national IAM fraction.

One noteworthy feature of this turn was that it knew few exemptions, particularly in the leadership. Unless you had a serious medical condition or were part of the small inner leadership circle, you went into industry. Party leaders were expected to lead the turn. Peter Camejo worked in a garment shop, Barry Sheppard in an oil refinery. If you were in the central leadership you might be expected go in for a couple of years, then be pulled out to work on a campaign, organize a new branch, or edit publications.

In the branches it was a little different. In some cases, pressure was brought to bear to get members to industrialize. Mostly, however, it was “patiently explain” and “lead by example.” Nonetheless, several hundred members –– who either held back from the turn, felt uncomfortable with the pressure, or went in and decided after a time it was not for them –– left the organization. Some became “active supporters” rather than full members. Many simply drifted away.

There were some recruits from the plants to replace those lost to the turn, especially before the Reagan era, before the crushing of the air traffic controllers’ strike. I recall seeing a report at a 1979 national steel faction meeting detailing the 35 workers recruited to the party out of the plants in the previous six months. “Not bad,” commented one veteran party trade unionist as we socialized at break.

Two years later we were recruiting very few. This was due to several factors, including the changing political climate. Some other groups on the left did nonetheless find ways to grow. The SWP by contrast had begun to convert “turn to industry” into workerist panacea, while drawing wagons in a circle in hopes of maintaining ideological purity in the midst of what was by then clearly becoming a deep period of reaction.

Illusions and Contradictions

The turn had been rolled out to the membership as a means of growing the party into a substantial force in the labor movement. The party press reported a “mass radicalization” underway among U.S. workers. Expectations ran high. At first all went well. There was much excitement and optimism. But when the Reagan reaction set in, things went south quickly.

The rightward drift in politics coincided with a series of internal political disputes in the party on theory and political orientation with much factional warfare, primarily coming from the majority leadership.

By early 1984, nearly 200 critics had been expelled. Along with them went dozens of majority supporters, who were either kicked out or encouraged to leave as the party leadership introduced ever more restrictive “proletarian norms” of membership.

The turn had been promoted as the big opportunity to break out of the “semi-sectarian existence” the party had been forced into since the McCarthy period. Now the organization rushed headlong back into that familiar mode of existence, transitioning to a hidebound sect in record time.

Contributing to all this was a major miscalculation made in late 1979, when the SWP leadership decided it was running out of colonizers and turned to the still vibrant, mostly student YSA. The SWP leadership decided that the YSA would “decide” that it too needed to turn to industry. The YSA would henceforth be an organization of young workers.

Many dozens heeded the call, quit school and entered the targeted industries, which soon included meatpacking, as strikes swept that industry. I remember helping recruit a student activist to the YSA, then to the party. She was persuaded to move to another branch to take a 60-hour-a-week job in a packinghouse. No one ever heard from her again — a tale often told.

By the mid-1980s, the SWP had lost half its membership, down to only some 800. With a leadership unable, or unwilling, to make corrections and change course, the decline continued unabated. Soon the remnant youth group collapsed and hundreds more drifted away. Today the SWP has about 100 formal members and perhaps 200 supporters, mostly former members –– an organization of no consequence. Having recruited few in recent decades its membership is now mostly retired, or nearly so –– a sorry tale.

But in the early days, the SWP’s turn to industry went well. The political motivation for the turn was well thought out and intelligently explained. It was argued that this was not a therapeutic move to purge the organization of alien class influences, but rather that of a revolutionary organization taking advantage of the first real opportunities since before the McCarthy period to win workers to socialism. Certain “therapeutic” blessings were in fact discovered, but that came later.

All those years since the 1950s witch hunt were characterized as “the long detour,” a period when the organization had been driven from its natural milieu –– the unions and the work places. Now with the turn, the party would be back on its historic course.

The errors and setbacks of the ’80s detract little from the achievements of the ’70s. The SWP had in fact organized its turn to industry in a methodical manner and with great success. The plants were hiring in the late-’70s, the peak of a business cycle. Members were assigned to watch the newspapers for employment ads.

When news came that an auto plant was about add a shift, word went out to the branches, and members were sent down to apply not only from local branches, but nationally. Many members transferred to other cities to get jobs where they were hiring and the party had targets.

Sometimes a member with previous manufacturing experience would get a job in a targeted plant. That member would then conduct informal classes to prepare others in the branch for the required employment tests.

Party members in Milwaukee applying at the two big General Motors parts plants trained each other in blueprint reading and use of micrometers and calipers. Members already in apprenticeships helped those preparing for an interview. Jobs committees researched industries, unions and hiring –– both for targets and for who to talk to in the union or the personnel office.

SWP branches got so good at this that when recession came in 1980 we still managed to get a great many people hired. You just needed to know where and how.

The deep recession of 1982-83 was a different matter. We still got members hired, but bore the labor of Sisyphus as plant after plant, mill after mill, closed. Some members laid off from industry went on full-time for the organization, while drawing extended unemployment benefits.

“Talking Socialism”

Though the SWP probably never had more than 700-800 members in industry at any one time in the period from 1978 until the recession of 1982, certainly well over a thousand passed through the plants, some staying just months, others decades.

Other industries the SWP targeted as the turn progressed were garment and coal mining, the former because it was among the most exploited sectors of the working class, the latter because of its importance in the economy and because of a militant strike wave, particularly the four-month 1978 national coal strike. At one time the SWP had two branches in the West Virginia coalfields and several dozen working in the mines.

In the mid-1980s the SWP, now much smaller, shifted a number of people from high-paying industrial jobs –– “the aristocracy of labor” — to low-wage garment shops, particularly in New York and Los Angeles. In Milwaukee we had small fractions at two union garment shops. It was not unusual then to see a party member three years into a machinist apprenticeship quit to take a job in a garment shop at less than half the pay. To assist members in their political work and recruitment in the plants many party branches conducted Spanish language classes.

Another industry in which the SWP had a significant presence was rail. At its high point the national rail fraction may have numbered a hundred. There was also at one point a national oil workers fraction of several dozen.

One union the SWP did not send members into was the Teamsters. Given the historic role of the SWP and its predecessors in that union this might seem strange, until one considers the presence in the Teamsters of the competing International Socialists and the formation they helped lead –– Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU). The SWP just stayed clear.

Party industrial fractions were organized not only on the national, but the local level. A small branch like Milwaukee, which only briefly numbered as many as 40 members, had at different times fractions in auto, rail, steel, garment and the machinists union.

Fractions at General Electric and General Motors, numbering a half dozen each, met regularly to discuss work on party campaigns, potential recruits, to plan union interventions, and how to defend against red-baiting, where that was a problem. Members lent each other support and assisted where individuals were running into difficulties –– with job skills, with management, with co-workers, with union officials.

There were many problems with the manner in which the SWP conducted itself in the trade unions. One was with the approach of “talking socialism.”

Although winning workers one-by-one to socialist ideas is a fundamental, how it is done is important. With the SWP there was a tendency toward propagandism –– measuring success in winning workers to socialism against the yardstick of socialist pamphlets or newspaper subscriptions sold.

A second and related problem was that of discouraging members from initiating struggles. When fights broke out we would participate — more often than not with stacks of socialist newspapers under our arms, but we were there. But the SWP did not, at least in this period, have a strategy for taking on the boss.

I had some firsthand experience with this. During the high tide of the “bosses’ counteroffensive” in the mid-1980s –– after Reagan had signaled to the entire employing class with his crushing of the air traffic controllers’ strike that it was open season on workers and unions –– we were confronted with concession demands at my steel plant that would have set us back decades.

When a concession proposal was voted down, union and company went back to the bargaining table. When we got the company’s “last, best and final offer,” we took a strike vote. The International rep and local union bargaining committee recommended a “yes” vote on the company offer with its steep wage and benefit cuts.

There were 500 union members at the meeting. I got up and spoke against the agreement and said we needed to strike. Afterward, the former union president told me he thought things hung in the balance until I spoke, that my speech resolved the issue. We struck the company for six weeks and got them to drop the worst of their concession demands.

When I reported what happened at the contract vote to my SWP branch I was roundly criticized for adventurism, that I was irresponsibly leading the workers into a fight they would not likely win, given current political conditions.

Besides, that was not why we were in the trade unions; we were not there to lead struggles. We were there to win workers to socialism. I left the party a couple years later.

Where’s the Radicalization?

There were other problems. The line was that the U.S. working class was undergoing a mass radicalization. The problem is, when members went into the plants for the first time, they had difficulty finding it. They knew there was a radicalization going on because they had read about it in the party newspaper –– it was just a matter of finding out where.

If your shop or industry seemed conservative, that was because the radicalization was obviously going on elsewhere. There were always greener pastures.

Consequently, there was an extraordinary amount of moving around. It was not unusual by the mid-’80s to meet party members who had already worked in three, four or more industries in as many cities in the few years of the turn.

Some of our European co-thinkers referred to this as the “grasshopper effect.” Comrades jumped from plant to plant, industry to industry, city to city, in perpetual search of the holy grail of the radicalization. The result was a rootless presence in the working class. The party’s relationship to the class was abstract and general, not concrete and specific. We were like itinerant missionaries to the working class, not part of it.

And more problems: though not prone to the sectarianism or ultraleftism displayed by some socialist groups, the SWP’s insistence that its members decline nomination for union office until such time as the working class was prepared to accept revolutionary leadership lent itself to a form of abstentionism. Members were discouraged from running even for shop steward –– advice that was sometimes ignored, especially in the early days of the turn before the central leadership took charge of directing the work.

This unwillingness to take leadership responsibility, for fear it might politically compromise us, meant that the SWP had an influence in this period far less than its numbers might suggest. Another socialist organization –– the International Socialists — with far fewer members but with a dynamic and well thought-out union strategy had a greater impact.

During my first 20 years in the steelworkers union I served on local union committees and was elected as a delegate to the central labor council and to district steelworker conventions, but held no local union office. When I dropped my formal party membership in 1988, I was elected shop steward, followed by financial secretary, then president of the 1,000-member local.

A decade later I was asked to go on staff for the International union. I retired in 2012 as sub-district director, responsible for the union in the southern half of Wisconsin. I remained an active socialist, a member of the revolutionary socialist organization, Solidarity, throughout.

My socialist politics were known in the union. Much had changed in the labor movement over the previous decades. Being a red was not such a big problem anymore. One fellow International rep loved to introduce me at conferences as his “favorite communist.” I was good with that.

November-December 2021, ATC 215

Before I comment on my experience in the SWP’s railroad fraction of 1970-72, a few words about Alice Peurala. By the late 1960s, Alice and her friend Dottie Peters, were – in my opinion – viewed as anomalies in the Chicago branch. They both had been members of the long gone Fox Tendency, and rarely spoke at branch meeting. In those years, Alice encouraged young comrades to “hire in” at Southworks, she had no takers.

In November 2014 Socialist Worker posted a useful article about Alice called Woman of Steel, here is an excerpt: ” (when Alice began at) the South Works mill in 1953, there were few women employed there. Most of the women who had steel jobs as a result of the Second World War had left those jobs when the men returned home. The women who remained faced gender discrimination in hiring and promotion. Still, Peurala found that most of the male steelworkers she encountered were pretty decent and helped her learn the tricks of the steelmaking trade that allowed her to do the job.”

The United Transportation Union was formed in 1969 as a consolidation of four smaller Brotherhoods, so its constitution had roots in an older, less democratic, craft union tradition. For example, members did not have the right to vote on contracts. This glaring omission was what drew the Socialist Workers Party into its first union work in nearly a decade.

Two Chicago branch comrades worked on the Milwaukee Road railroad in 1967. One, Dan Styron, lasted about a year, the other, Ed Heisler is central to the story of the SWP’S railroad work.(Full disclosure, Ed was revealed to have been an FBI informant through COINTELPRO findings 10 years later).

In 1968 Heisler was joined as a Milwaukee Road switchman by David Rollins. If Ed was known as a flashy good public speaker and prima donna, Davy was known for being just the opposite. Davy was a blue collar army veteran, who had worked as a truck driver in New York. He immediately won the respect and trust of his fellow workers on the railroad.

Sometime in early 1970 (after 50 plus years my dates are “best guesses”) the United Transportation Union’s (UTU) contract was on the agenda. Heisler and Davy Rollins spoke from the floor at their local’s monthly meeting about the democratic need for the membership to have the right to vote on contracts. The local agreed, and decided to form a committee to organize around that issue. Heisler and Rollins were asked to head the Right To Vote Committee, and a movement was born.

Before consolidation trimmed the numbers, there were over 2 dozen UTU locals in the Chicago area alone, and at least that many more within driving distance. The Right to Vote had a built-in potential base. When the SWP’s national office was informed of this development, Frank Lovell recognized it as something the party should be involved in. It was largely Frank’s baby. Now, a fraction was born.

The first person asked by the SWP to specifically get a railroad job and form a fraction was Paul De Veze. Paul, a New York transplant, was a pefect fit. He hired out on the Milwaukee Road sometime in the spring of 1970. The young fraction had a mouth in Ed Heisler, a heart in Davy Rollins, and a brain in Paul De Veze.

The next addition was Bill Banta. Bill was a full time AFSCME organizer when he ran across the YSA in De Kalb, Illinois. De Kalb was, and is, the home of Northern Illinois University (NIU). The staff at NIU was organized by AFSCME and Bill was sent there to help with a strike. The NIU YSA worked in solidarity with the strike and the connection was made. Bill, joined the SWP, quit his job at AFSCME, and became a switchma on the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O)

In the summer of 1970 Antonio De Leon was also hired by the B&O, first as car repairman, and later as a switchman. Antonio was a Chicago born Mexican American who joined the YSA as an activist in the Grape Boycott and in the antiwar movement while he attended Loop Junior College.

I was the sixth person who rounded out the core of the Chicago railroad fraction. I joined the YSA shortly after being discharged from the U.S. Army in October, 1967. Since I was the only young veteran in the Chicago YSA I was assigned to GI work, which was then a major focus of the YSA/SWP. I helped found three GI newspapers at Ft. Sheridan, Great Lakes Naval Center and an Air Force base in Rantoul Illinois. After the Jim Miles letter, the party’s focus on GI work was de-emphasized.

After the Kent State massacre, the party asked me go to Washington D.C. as temporary help in the national Student Mobilization Committee. When I came back to Chicago in early June of 1970, I was sent to San Diego to work on the impressive California SWP election campaign. When the election was over, sometime around Thanksgiving of 1970, I received a call from Frank Lovell. Apparently, Ed Heisler had recommended me as someone who would be useful in the party’s railroad work.

In December of 1970 I returned to Chicago and applied for work at 6 or 7 railroads, and was accepted at three. Of the three, I was advised that the Chicagi & Northwestern (CNW) had the biggest UTU local (actually there were two large CNW UTU locals in Chicago, 528 and 577). I began my 38 year railroad career on December 22, 1970.

The Chicago fraction worked on the City-wide Right to Vote Committee. We leafletted two dozen railroayards and the four major commutter depots on a regular basis. The six of us in the fraction attended local meetings across the region. Usually we went in twos. Our fraction meetings were always attended by the branch organizee, Pearl Chertov. Fred Halsted, who lived in Chicago in the early 1970s also attended. At least once a month Frank Lovell flew into Chicago to oversee our work.

Several more comrades joined the fraction in 1972, but by then our work was no longer a priority. Once the Right to Vote became a national movement and was accepted by the union as a democratic right, much of our raison d’etat disappeared. Several of us wanted to publish a newsletter and go deeper into union politics, but that was not be. Barry Shepard came to Chicago with the SWP National office decision to liquidate the fraction. In the late 1970s there was a second incarnation of the Chicago railroad fraction but that’s another story.

Thanks Guy for your story. I remember Frank Lovell for the role he played in auto rank and file work. It’s nice to hear about the SWP playing a role in building union democracy. In the 1990’s there were about 5 SWP members in my auto plant where I had industrialized in 1972. I got elected President in 1999 and fought in negotiations against two tier wages and benefits. I was tremendously under the gun from the company and union bureaucracy but the SWP members refused to play any role around in-plant and union democracy issues at that time. They just sold books. It was too bad because their involvement would have helped a lot!

Thanks for the report and the commentaries. Unless I’m not mistaken, none of those industrial fractions that were started in the 1970s still exist..

Jack Shepherd’s last name was not spelled the same way that Barry’s is. If my recollection is correct Paul Devez lives here in Southern California of in California, in Orange County.

So what was the labor strategy of the IS?

These are interesting reports. I was struck by Bill’s mention of 35 people being recruited out of industry in the late 70’s. I hadn’t remembered that. He goes on to mention that quickly dried up a couple years later, which is what I remember.

I remember a report by Malik Miah which was actually quite sober in looking at the political level of US workers – he said the workers were “political babes in the woods.” No conclusions were drawn from this though.

Personally I joined the movement in 1970 at the U of I Chicago Circle, and later drove taxis before the turn, then worked 3 years in an aluminum mill in Phoenix, then 16 years in auto plants in Toledo and Twin Cities, before resigning in ‘99, then being expelled from being a supporter in 2000 after writing a letter to The Militant supporting the government’s returning of Elian Gonzalez to his father.

I tried to be creative with union activities like organizing MLK programs, strike support activities, and participating in job fights against speed-up.

I think the party could have done some industrial colonization without kiboshing fractions in teachers’ unions and AFSCME. And without dissolving the YSA into the turn. And if we had continued to work to lead antiwar and anti-racist protests, along with Cuba solidarity work the party could be a very viable organization today with a fair number of young people.

But could have beens don’t do a whole lot.

Thanks, Walter, for correction on spelling of Jack Shepard’s name. Concerning the 35 recruits out of industry, Joe––if I still had all my internal bulletins and the handouts from the steel factions (all of which I attended) I could back that up. But, alas, I donated all those to a library collection some years ago. The conversation I had at break at the national steel fraction I remember being with Steve Chase and Joe Ward. I remember what we saw in the written report like it was yesterday. All these recruits from industry came in during the “Lenin levy” period, when probationary membership was first introduced and we were recruiting in relatively large numbers. I know that in my old branch in St. Louis (after I had moved to Milwaukee) ten were voted into membership at a single meeting. Similar things happened elsewhere. Membership norms were relaxed––correctly, I think––for a period allowing for this kind of recruitment. It was during this period that the ephemeral industrial recruitment I cite took place. I should note that I wrote this piece in 2018 in response to a questionnaire from the DSA Labor Commission. An early draft was circulated online, and I got feedback from a number of former members telling me I had gotten this or that wrong. I made some adjustments. So it has been vetted to a degree. Curiously, one criticisms I heard––at least three times––was that I had underestimated the size of one or another national fraction. On another note: Thanks to Guy and Wendy for their remembrances. They help illustrate points I sought to make.

Guy, can you elaborate on the Jim Miles letter?