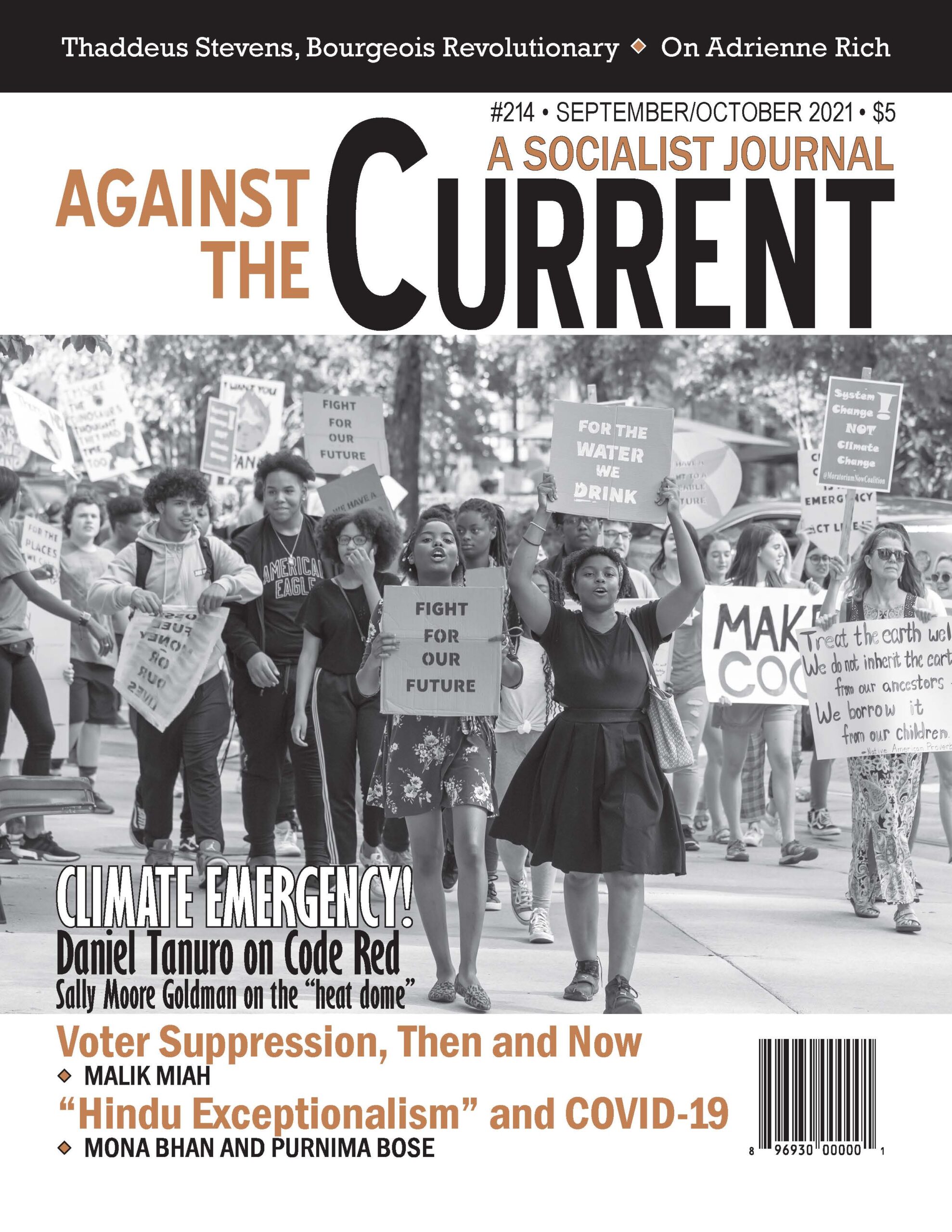

Against the Current No. 214, September/October 2021

-

Facing the Long J6 Riot

— The Editors -

What the Cuban Protests Reveal

— The Editors -

One Member, One Vote: Taking Back Our Union

— Dianne Feeley -

Alabama Strike Continues

— Zack Carter and Dianne Feeley -

On the Brink of the Abyss

— Daniel Tanuro -

Life Under the Heat Dome

— Sally Moore Goldman -

Why Do Socialists Oppose Zionism?

— David Finkel -

An Ethnic Cleansing Rampage

— David Finkel -

On Israel's New Government

— Suzi Weissman interviews Yoav Peled - Whistleblower Hero: In Praise of Daniel Hale

- Guatemala: Strike and Crisis

-

Confronting Voter Suppression

— Malik Miah -

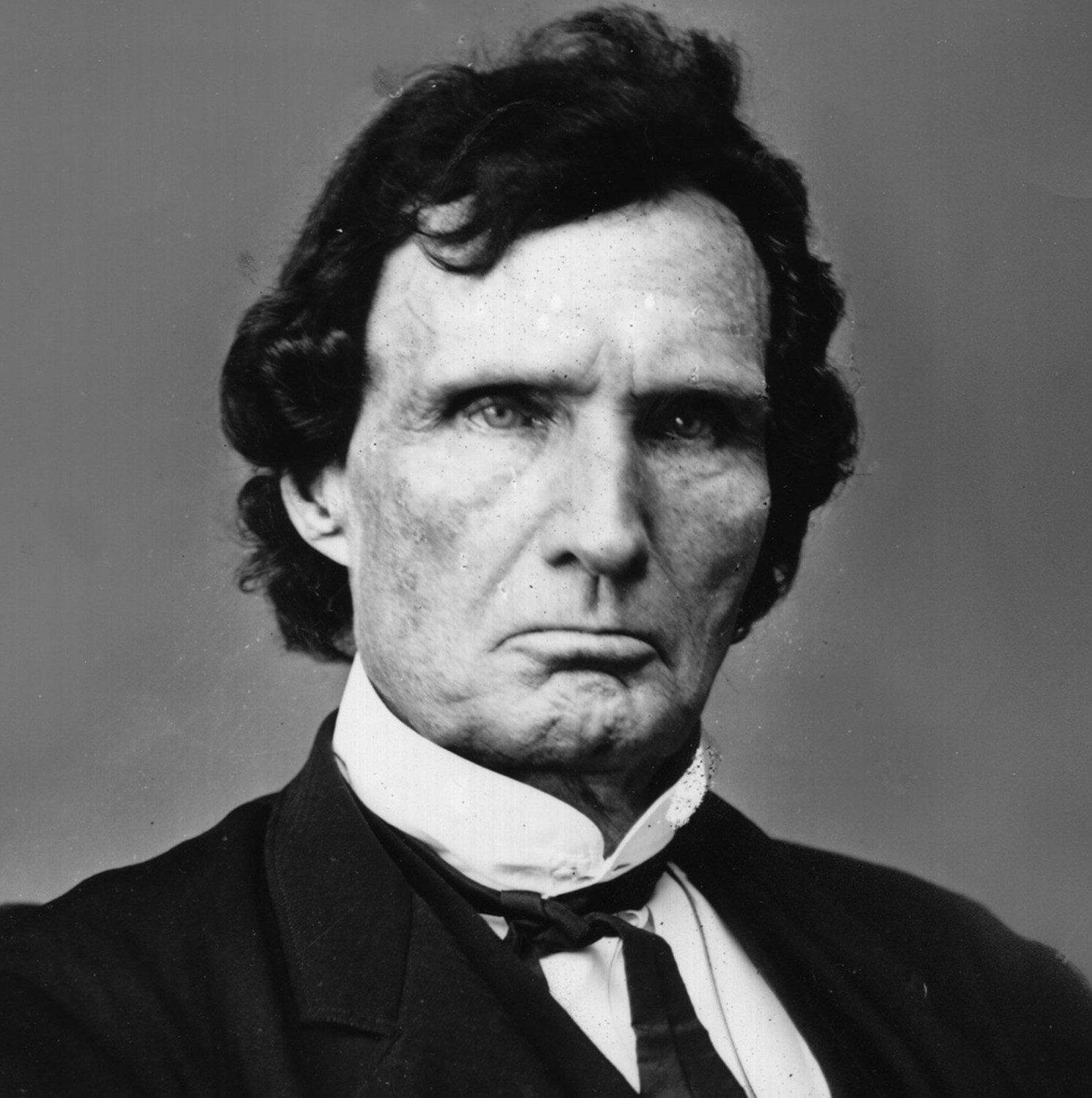

Thaddeus Stevens: Bourgeois Revolutionary

— Bruce Levine -

Rosa Luxemburg & Trotsky

— Michael Löwy -

Hindu Exceptionalism and COVID-19

— Mona Bhan and Purnima Bose - Review Essay

-

Adrienne Rich, Trailblazer

— Peter Drucker - Reviews

-

A Memoir of Anti-Racist Struggle

— Dick J. Reavis -

Inner Lives in Hard Times

— Lukas Moe -

A Study in "Populist" Racism

— Yoav Peled -

Dialectics of Progress and Regression

— Jake Ehrlich -

Challenges for Democratic Socialists

— Dan Georgakas -

The Many Lives of Money

— Folko Mueller -

Reading Walter Benjamin Politically

— Joe Stapleton

Bruce Levine

THE AMERICAN AND French Revolutions of the late 18th century opened an era marked by what Marxists call bourgeois-democratic revolutions.(1) These are struggles to overturn pre-capitalist social relations and institutions and to win “bourgeois-democratic rights” — rights, that is, that abet the development of capitalism or, at least, do not intrinsically challenge capitalism’s existence.

Such rights include national unification and independence; republican rather than monarchical or other authoritarian forms of government; personal civil, legal, and political equality; and land reform, including the removal of feudal or other oppressive pre-capitalist relations on the land.

The Civil War waged in the United States between 1861 and 1865 belonged to this family of revolutions. The Union forces in that war at first fought principally to resist the nation’s dismemberment at slaveowners’ hands. But eventually the Union’s war program expanded to include emancipation of the South’s slaves, who accounted for almost forty percent of the population of the insurrectionary states.

That, as Karl Marx recognized from afar, represented “a gigantic revolution” in U.S. society.(2) The Pennsylvanian congressman Thaddeus Stevens played a leading role in that revolution. Rather than summarize my recently published book about Stevens, this essay tries to elaborate further some themes that may be of particular interest to readers of this journal.(3)

The Role of Leadership

But neither Abraham Lincoln nor his party’s majority set out at first to impose such a radical social change upon the South. It was, instead, the intrinsic logic of the wartime conflict — the necessity of attacking slavery in order to defeat the slaveholders’ insurrection — that led the Union president and his party as a whole, step by step, into what Lincoln finally acknowledged to be “a revolution of labor.”

But of course, the intrinsic logic of a situation does not by itself ensure its translation into appropriate action, does not ensure that those involved will be guided by that logic in their conduct. For that to happen, someone must first of all recognize that objective logic, formulate a program informed by it, and win others over to that program. In other words, adequate leadership is required.

Carl Schurz, a prominent Midwest Republican, later claimed that “emancipation would have been declared in this war, even if there had not been a single abolitionist in America before the war. … Nay, [even] if there had been a lifelong pro-slavery man in the Presidential chair,” so long as he was also “a Union man of a true heart and a clear head ….’”(4)

But the fact is that in the Union in 1862-63, heads clear enough to see and hearts courageous enough to do what the Union’s survival required were not in excess supply.

Although many northern Democrats, thus, sincerely supported a war to preserve the Union, few of them recognized the necessity of emancipation. Those who did not included both the head of the Union army, George McClellan, and Lincoln’s own Secretary of State, William Seward — the man who had nearly been the Republican party’s presidential candidate in 1860.

For the situation’s intrinsic logic to yield positive antislavery policy, someone needed to open the Union’s (and the Republican Party’s) eyes to that logic. Pennsylvania congressman Thaddeus Stevens played a key role in doing that.

Recognizing early on that the fight against the secessionists had created a revolutionary situation, Stevens began deliberately to formulate a revolutionary response to it and to demand its implementation. At each stage in the war’s evolution, Stevens pressed the populace and politicians (including Lincoln) for greater antislavery radicalism.

Then when the war eventually ended, Stevens persevered, insisting upon civil and then political equality for African Americans during the Reconstruction era. In doing that, he continued to march ahead of his party’s majority.

While hesitant Republican moderates viewed Reconstruction as a legally and politically vexing problem, Stevens regarded it as an opportunity — an opportunity to complete (or, in his words, “perfect”) the revolutionary transformation of the nation that began during the war itself.

Pro-Capitalism and Anti-Slavery

Historians and biographers have not neglected Stevens. About a dozen book-length studies about him have appeared, all of which contain valuable information. But none of them clearly identify the specific nature of Stevens’ core beliefs, leaving his particular politics and the historical context in which they took shape inadequately explained.

One able historian thought it enough to label him rather vaguely a “nineteenth-century egalitarian.” Another, gazing balefully upon Stevens’ devotion to capitalist development, refused on that account to regard Stevens as any kind of egalitarian at all.(5)

Both those authors missed their mark. The first failed to specify the kind of equality for which Stevens stood, thereby ignoring the fact that self-styled “egalitarians” came in many shapes and sizes in the 1800s (as, of course, they still do). The second author erred by flatly counterposing pro-capitalism and anti-slavery to one another, seeing the two causes as necessarily distinct and even in contradiction with one another.

But in Thaddeus Stevens’ eyes, they were inseparably intertwined. Slavery — and white supremacy more generally — profoundly repelled him morally; his words and actions make that abundantly clear. But that revulsion did not conflict with Stevens’ general bourgeois views on political economy and philosophy; the two went hand in hand.

From his youth, like many intellectual and political figures of his day, Thaddeus Stevens regarded the development of capitalism (then often referred to in the U.S. North simply as “free-labor society”) and the spread of its values as the salvation of society as a whole, as key to humanity’s liberation from oppressive, anachronistic social relations and backward beliefs.

Thus, while one of his college texts praised Christianity as the source of moral progress, the young Stevens held instead that it was economic development “that has banished barbarism, despotism, and superstition from a great portion of the globe.”

In appraising and depicting capitalism in this way, Stevens conformed to a general pattern that Marx and Engels discerned. A rising class that aspires to reshape society in accord with its own needs and values, they saw, “is compelled, merely in order to carry through its aim, to represent its interest as the common interest of all the members of society,” is compelled to “give its ideas the form of universality, and represent them as the only rational, universally valid ones.”

Such a rising class can do that more convincingly to the degree that “its interest really is more connected with the common interest of all other non-ruling classes,” and if the internal contradictions of the kind of society that it champions are as yet less sharp, less obvious.(6)

In 1860, the average manufacturing enterprise employed fewer than ten people and upward mobility in the North in that era was drastically greater than it would be when capitalism developed further. At that early stage of industrial capitalism’s development in the United States, people like Stevens considered its manifold superiority over chattel slavery self-evident and had little trouble convincing most of the North’s population of the same thing.

Some of Stevens’ biographers have suggested that his radicalism owed something to his being born lame, with a club foot, therefore beginning early to empathize with disadvantaged people generally. Maybe so, just as it’s conceivable that their physical infirmities inclined the young Rosa Luxemburg and Antonio Gramsci to the left many decades later.

But we have better reason to credit other factors in Stevens’ early years with influencing his ideological development. He was born and grew up in a state, Vermont, with an exceptionally radical-democratic recent past, political heritage, and political culture.

His family was poor, a fact to which he later attributed his identification with and wish to better the condition of the impoverished and downtrodden generally. His own successful effort to escape the poverty of his youth no doubt reinforced his devotion to the capitalist economy that had made that escape possible.

Meanwhile, his family’s Baptist faith, which traced its ancestry back to the 17th-century revolution in England that overthrew the monarchy, encouraged individual conscience, personal choice, and community solidarity. College education exposed him to books infused with the spirit of the bourgeois Enlightenment.(7)

All these external influences — and key aspects of his personality, including a strong will, a combative nature and personal courage — would determine the manner in which he would subsequently evaluate and respond to political developments.

To be sure, not all of these factors tended to push him in the same direction ideologically. He would have to work out inconsistencies as he made his way through life. But all the influences noted above did combine to foster in Stevens an early hostility to chattel slavery.

Vermont’s unusually democratic state constitution was the first in North America to explicitly condemn the enslavement of human beings. New England Baptists proved receptive to abolitionism.

His formal education confirmed and reinforced his antislavery views. Stevens later recalled reading Greek and Roman classics in his youth that “denounced slavery as a thing which took away half the man and degraded human beings, and sang paeans in the noblest strains to the goddess of liberty.”

One of the most important books assigned to him in college scorned slavery as an abomination, in accord with the liberal bourgeois principle that while wealth inequality born of market forces were legitimate, oppression and exploitation imposed by physical force, legal or otherwise, was not.

Evolution of a Revolutionary

So Stevens’ repugnance toward slavery was pronounced by the time he graduated college and moved to Pennsylvania in search of work, first as a teacher and then as a lawyer, and still later as a politician. But he was not at first ready to make that sentiment central to his professional or political life.

It would require the passage of additional years and the cumulative impact of one slavery-spawned national political crisis after another, from the 1830s through the mid-1850s, to show him that this was indeed the central question of the age and to forge him into the steely, aggressive, bourgeois revolutionary that he eventually became.

One milestone along that route of political evolution came in the mid-1830s, as slaveholders and their allies escalated their attacks on all forms of antislavery speech and action and demanded that the free states aid them in those attacks. Those developments helped deepen and make more consistent Stevens’ dedication to the antislavery cause.

Another turning point came when the United States, prodded especially by slaveholders, declared war on Mexico in 1846 and proceeded to steal half of that nation’s land mass. Stevens opposed the war and denounced Congress’s 1850 decision to permit slavery’s expansion into the newly acquired land.

Four years later, Congress bowed yet again before the South, this time opening the door to slavery in federal territories previously closed to it. That decision provoked a huge northern outcry that birthed the antislavery Republican Party. Stevens soon helped to found it in his state and in 1858 gained election to the House of Representatives on the young party’s ticket.

When that same party’s presidential candidate won the election two years later, slaveholder leaders, concluding that slavery was now doomed in the United States, launched the insurrection that became civil war.

The Second American Revolution

Under certain circumstances, a rising capitalist class and its allies can overturn slavery, feudalism, or other pre-capitalist relations and institutions without violent conflict. That is most likely where an old and declining ruling class has lost confidence in itself and especially in its ability to resist demise.

But that was not the case in the United States in 1860. Slavery there remained immensely profitable and seemed likely to remain so indefinitely. Other factors also bolstered the strength and audacity of the slaveholding elite.

Slave-based agriculture, on the one hand, and a still young industrial capitalist economy, on the other, dominated geographically distinct parts of the country. In the South, and especially in the cotton kingdom of the lower South, the planter class continued to enjoy not only economic but also social and political hegemony; most slave-less whites there remained under its influence.

When the slaveholding elite did see its political power declining at the national level in the late 1850s, its own long-accustomed regional power left it confident in its own strength and future. That confidence encouraged it to protect its interests aggressively, forcibly tearing its geographical stronghold out of the Union and creating a new country safe for slavery.

For both economic and political reasons, the bourgeoisie and the rest of the northern population could not allow that to happen. The consequence was war.

For Stevens, the Civil War fused necessity and opportunity. He had wished throughout his adult life for slavery’s speedy disappearance; here, finally, was the chance to accomplish that.

But he also believed that Union victory in the war would require supplementing a purely military struggle with a frontal attack upon slavery because it was the mainstay of both southern society and the South’s war effort.

Stevens was therefore among the first in Congress to call for confiscating the slaves of Confederate rebels; to demand full legal freedom for slaves who were so confiscated; to demand bringing African Americans into the Union’s until-then lily-white armies; to call for widening the scope of emancipation to include all slaves within the rebellious states.

He was also among the first to press for outlawing slavery throughout the United States as a whole — to press for a constitutional amendment that would outlaw the enslavement of any human being anywhere in the country. He did that a full year before Abraham Lincoln endorsed the idea.

Stevens clearly understood that these steps would mean a radical transformation — a social and political revolution — in southern society. He fully embraced that transformation.

He repeatedly argued that “We must treat this war as a radical revolution” and “revolutionize Southern institutions, habits, and manners. . . The foundations of their institutions. . . must be broken up and relaid, or all our blood and treasure have been spent in vain.”

Land Reform

For Stevens, the democratic transformation of the South would be incomplete without something else common to other bourgeois democratic revolutions — land reform, which in this case called for breaking up the slave plantations into small farms for the freedpeople.

Stevens did not originate that idea. All over the South, emancipated slaves sought both during and after the war to take the land of their ex-masters and cultivate it for themselves. It seemed obvious to them that centuries of unpaid Black labor had more than paid for those acres.

President Lincoln did briefly consider making it easier for Black southerners at least to buy federally-controlled land. But his administration soon abandoned even that idea and Lincoln ultimately decided that property-less and impoverished former slaves would have to depend on their own efforts alone if they were to survive economically. (“Root, hog, or die,” was the advice Lincoln thought appropriate, using a then-familiar phrase that meant “find your own sustenance or starve.”)

On this subject too, Stevens strongly disagreed with Lincoln. Always a believer in active government, he had never relied solely upon the market’s “invisible hand” to create or guide the equitable kind of capitalist society that he hoped for. So now the Pennsylvanian repeatedly urged Congress to confiscate the estates of the South’s major planters and divide them among their former slaves.

“It is impossible that any practical equality of rights can exist,” Stevens insisted in the fall of 1865, “where a few thousand men monopolize the whole landed property.” For “how can republican institutions, free schools, free churches, free social intercourse exist” in a society composed of “nabobs and serfs”?

There was nothing intrinsically anti-capitalist, much less socialistic, in calls to confiscate and divide the slaveowners’ estates. Marx argued, indeed, that landlordism economically constrained the development of capitalism. Lenin likewise contended (regarding the 1905 Russian Revolution) that “the ‘ideally’ pure development of capitalism in agriculture” required the nationalization (meaning state ownership, not collective cultivation) of all land.

But as Marx understood, “in practice” the capitalist “lacks the courage” to nationalize the land, “since an attack on one form of property … might cast considerable doubts on the other form” — that is, private property in industry.(8)

Marx’s observation held true in the United States. Stevens’ proposal to confiscate and break up plantations into small, freedpeople-owned farms fell far short of nationalization. But the U.S. capitalist class and its spokesmen (including even some Republican radicals) nevertheless rejected the notion.

As a couple of major northern newspapers bluntly explained, they could not tolerate the large-scale confiscation of landed property in peacetime, lest doing so encourage wage workers in the North to follow suit by trying to confiscate workshops, factories, etc. there.

Thaddeus Stevens, although a lifelong champion of capitalism and himself a longtime owner of an iron works, was one of very few members of his class to display no such fears. Here as on many other occasions and in many other places, an ardent bourgeois revolutionary found himself opposed by hidebound members of the very class whose presumed interests and principles he sought to advance.

The Reaction

Beginning in the 1870s, white supremacists in the South overturned most of the gains of the Reconstruction era. By the 1890s, as Frederick Douglass recorded, “In most of the Southern States the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments are virtually nullified. The rights which they were intended to guarantee are denied and held in contempt. The citizenship granted in the fourteenth amendment is practically a mockery, and the right to vote, provided for in the fifteenth amendment, is literally stamped out in face of government.”

The same was true, he added, of the economic situation of the Black American, having been, upon emancipation, ”sent away empty-handed, without money, without friends and without a foot of land upon which to stand.” Therefore, “though no longer a slave, he is in a thralldom grievous and intolerable, compelled to work for whatever his employer is pleased to pay him.”(9)

Thaddeus Stevens had died in the summer of 1868 at the age of 76. But if he had lived longer, could he have prevented Reconstruction’s eventual overturn? For that matter, could Abraham Lincoln have done so?

No. The fate of any kind of radical social or political change depends upon the presence of at least two conditions: not only able radical leaders but also, and still more fundamentally, the kind of objective circumstances that enable those able radicals to lead, circumstances that make their proposals compelling to many others and thereby empower them politically.

For antislavery radicals, those objective circumstances did not fully exist until the end of the 1850s. By the later 1870s, they existed no longer.

At that point, white supremacists far outnumbered freedpeople in the South and had infinitely greater resources at hand. The freedpeople’s southern white allies were too few and too unreliable. In the North, the bourgeois conservatism that doomed land reform in 1866-67 only deepened in the decades that followed.

With the obstacle of slavery removed and the South’s once formidable anti-industrial influence in Washington weakened, industrial capitalism grew mightily. But so, therefore, did the size of the country’s wage-earning working class. And the postwar militancy of that class angered and frightened northern businessmen, whose interest in the rights and welfare of any laborers, least of all Black ones, cooled apace.

In 1873 a major economic depression hit the country as a whole, a depression that many capitalists attributed to continuing social and political turmoil in the South. That depression therefore further soured them on federal action there.

A major Republican businessman in New York spoke for many others when he declared that “what the South now needs is capital to develop her resources, but this she cannot obtain till confidence in her state governments can be restored, and this will never be done by federal bayonets. We have tried this long enough. Now let the South alone.”(10)

When depression-spawned severe wage cuts sparked a nationwide labor uprising in 1877, the editor of the once semi-radical magazine The Nation blamed “some of the talk about the laborer and his rights that we have listened to … during the last fifteen years, and of the supposed capacity of even the most ignorant, such as the South Carolina fieldhand, to reason upon and even manage the interests of a great community.”(11)

Betrayed by their onetime allies in the northern elite, therefore, and receiving scant attention and no active solidarity from the North’s growing but short-sighted and racism-plagued labor movement, African Americans in the South now faced white supremacist forces alone.

As the capitalists disowned and turned their back on that revolution, academics and producers of popular culture followed their lead. Scholarly volumes, popular history books, and Hollywood films about that era long demonized the radical Republicans, especially Thaddeus Stevens.(12)

It would take the mass mobilizations of the modern civil rights movement and the changes that it brought about in cultural norms to induce academia, publishers and film-makers to rethink at least some of their inherited prejudices about slavery and emancipation, Thaddeus Stevens and the Second American Revolution.

Completing that revolution’s tasks and building on those foundations a genuinely multi-racial and egalitarian society will be the work of the Third American Revolution.

Notes

Notes

- Events like the 17th-century revolution in England in some ways anticipated the eruptions of the late 18th. Probably the best take on that subject is Christopher Hill, “A Bourgeois Revolution?” in The Collected Essays of Christopher Hill, 3 vols. (Amherst, MA, 1985), vol. 3, 94-124. But it was after the American and French revolutions that bourgeois-democratic revolutions began to multiply dramatically.

back to text - Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works, 50 vols. (Progress Publishers, 1975–2005), vol. 42: 48.

back to text - Thaddeus Stevens: Civil War Revolutionary, Fighter for Racial Justice (New York, 2021).

back to text - Carl Schurz, Speeches, Correspondence, & Political Papers(New York, 1913), vol. 1, 232. Emphasis added.

back to text - Hans L. Trefousse, Thaddeus Stevens: Nineteenth-Century Egalitarian (Chapel Hill, NC, 1997); Richard N. Current, Old Thad Stevens: A Story of Ambition (Madison, WI, 1942). In an essay widely cited by left-leaning scholars, Margaret Shortreed did try to depict Stevens as a bourgeois revolutionary. But she too ascribed to him and his cohort a narrow, economics-preoccupied understanding of bourgeois class interest that eclipsed any kind of ethical revulsion toward slavery. See Shortreed, “The Antislavery Radicals,” Past and Present, vol. 16 (Nov. 1959), 65-87. Missing from all such attempts to counterpose morality to economics is recognition that a specifically bourgeois, but no less real and compelling, ethical hostility to chattel slavery clearly did play an important role in bringing on the Second American Revolution.

back to text - From The German Ideology (1846), in Marx and Engels, Collected Works,> vol. 5, 60-61.

back to text - Later, observers would often liken Stevens to Maximilien Robespierre, the Jacobin leader during the most radical phase of the French revolution. And there were indeed some striking parallels there. Each man (as one biographer notes of Robespierre) “brought to his participation in the Revolution values and beliefs that had developed across … decades of family life, schooling, and work.” Both spent their youths in provincial parts of their countries and experienced personal hardship there. Both chafed at those difficulties, hungered for an education and advancement, and managed to reach those goals. In school, each devoured ancient republican classics as well as works of the European Enlightenment that extolled ideals of bourgeois liberalism. Both went on to become skilled, witty lawyers, ardent foes of aristocratic privileges and caste, and champions of bourgeois equality. The quoted words are those of Peter McPhee, Robespierre: A Revolutionary Life (New Haven, 2012), xix, 1-61. But see also Albert Soboul, “Robespierre and the Popular Movement of 1793–4,” ast and Present, vol. 5 (May 1954), 54–70.

back to text - Karl Marx, Theories of Surplus-Value, Part II (Moscow, 1968), 42-45; Lenin, “The Agrarian Programme of the Social-Democracy in the First Russian Revolution, 1905-1907” (1907), in his Collected Works (Moscow, 1962), vol. 13, 314-21.

back to text - Life & Times of Frederick Douglass (originally published in 1892; reprint, London, 1962), 501-504.

back to text - Kenneth M. Stampp, The Era of Reconstruction, 1865-1877 (New York, 1965), 207.

back to text - Leon Litwack, ed., The American Labor Movement (Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1962), 53-56. On northern capital’s reaction to the demands of wage earners in these years, see David Montgomery, Beyond Equality: Labor and the Radical Republicans, 1862–1872 (New York, 1967), and Heather Cox Richardson, The Death of Reconstruction: Race, Labor, and Politics in the Post–Civil War North, 1865–1901 (Cambridge, MA, 2001).

back to text - In this respect, they marched in lock step with the French bourgeoisie and both conservative and liberal intellectuals, who used the bicentennial of the Great French Revolution to disown, vilify, and slander that magnificent popular upheaval.

back to text

September-October 2021, ATC 214