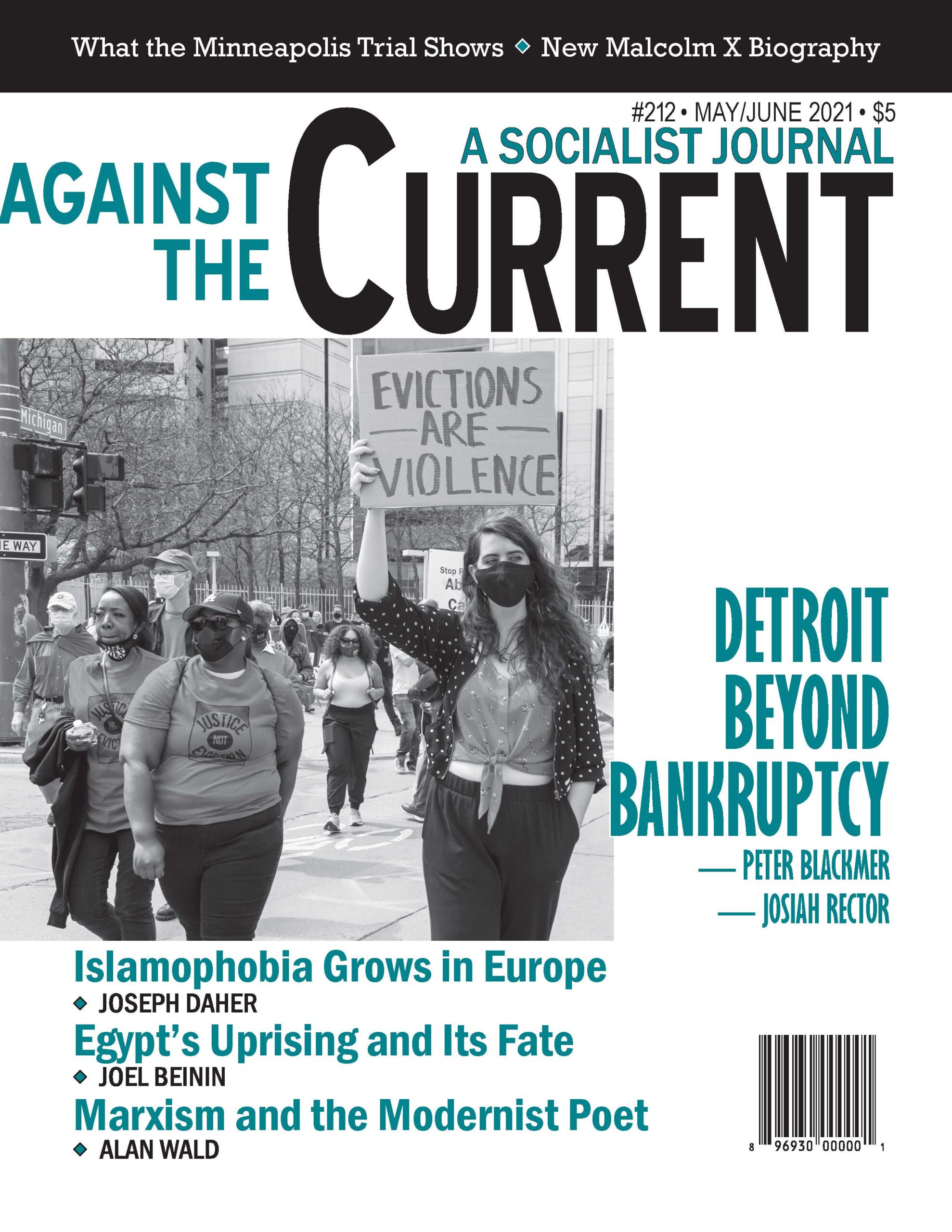

Against the Current No. 212, May/June 2021

-

Biden: "Empire Is Back"...

— The Editors -

Conviction on All Three Counts in Chauvin Trial, Bail Revoked

— Malik Miah -

Bravery, Not Blowout

— John Logan -

Egypt's Uprising and Its Fate

— Joel Beinin - Solidarity with Myanmar Peoples

-

Islamophobia in Europe

— Joseph Daher -

Marxism and the Modernist Poet

— Alan Wald -

What Method of Organizing?

— Marian Swerdlow - Tulsa's Buried Massacre, 1921-2021

- Solidarity with Kshama Sawant

- Urban Crisis

-

Detroit's Tale of Two Water Crises

— Josiah Rector -

Detroit, Comeback & Austerity: State of the City

— Peter Blackmer - Reviews

-

Bringing Malcolm to Life

— Malik Miah -

The Empire's New Forms

— Keith Gilyard -

Healing Politics -- A Doctor's Story

— Susan Steigerwalt -

Venezuela: Things Fall Apart

— Carlos G. Torrealba M. -

Danger on the Shop Floor

— Toni Gilpin -

Stirring the Dust of Archives

— Noa Saunders -

Shifting Identities in a Settler Land

— Listen Chen -

Fictionally Comprehending Trotsky

— Paul LeBlanc - In Memoriam

-

Karen Lewis, 1953-2021

— Dianne Feeley

Carlos G. Torrealba M.

Venezuelans Under Siege/Venezuela frente las sanciones

Co-directors/producers: Atenea Jiménez Lemon and Kevin Young

42-minute film in English and Spanish, June 2019, available on YouTube

IN VENEZUELANS UNDER SIEGE, Atenea Jiménez Lemon and Kevin Young show the impact of U.S. sanctions on Venezuela and how Venezuelans have responded.

Atenea Jiménez Lemon is a sociologist, founder of the Red Nacional de Comuner@s in Venezuela and the Universidad Campesina de Venezuela Argimiro Gabaldón. She also edited La Toparquía Comunera, concreción de la utopía (2014). Kevin A. Young is a professor of Latin American History at the University of Massachusetts. He is author of Blood of the Earth: Resource Nationalism, Revolution, and Empire in Bolivia (2017) and editor of Making the Revolution: Histories of the Latin American Left (2019). They recently published a study on USA policies towards Latin America “Letting Latin America Live” in NACLA (Spring 2020).

Life Under Sanctions

The film draws on interviews with Venezuelans, both specialists and community activists. It portrays the devastating effect of sanctions both nationally and in everyday life — and how despite the hardship Venezuelans seek solutions and alternatives.

The allure of the documentary is that it involves a plurality of speakers: working-class people, women from the barrio, afrovenezuelans and members of the community. Also included are Professor Carlos Lazo and Manuel Sutherland from the Center for Research and Worker Training as well as a staff member from the nationalized power corporation (CORPOELEC).

The documentary begins with a summary of U.S. relations with Venezuela since the Chavista revolution. It reveals Washington’s hostile and bipartisan foreign policy, one which became even more aggressive under the Trump presidency. This overview is valuable because there is much confusion over the purpose and function of sanctions.

On August 24, 2017 Trump issued an executive order against the Venezuelan State. It prohibited negotiations on debts and bonds with the government and PDVSA, the national oil company. Trump also refused to allow Venezuelan companies based on North American soil, particuarly CITGO, to transfer its dividend money home.

The second important sanction, issued in January 25, 2019, directly targeted PDVSA. This order prohibited American citizens and corporations from any international exchange with Venezuelan subsidiaries. For this reason, no one wants to acquire Venezuelan and PDVSA bonds; current bondholders refuse to negotiate restructuring. Trump also pressured other governments into blocking Venezuela’s access to its foreign assets, effectively freezing five billion dollars.

Jiménez Lemon and Young are right to emphasize that these sanctions are not isolated actions. They trace a pattern of opposing the Chavista government with U.S. support to the failed coup in 2002, the oil strike between 2002 and 2003 and by financing its opposition.

After Juan Guaidó annointed himself the country’s president, Trump immediately recognized him, essentially backing his attempt to overthrow the Maduro government. Sadly, President Biden has not ended these sanctions or withdrawn recognition of Guaidó.

Definitely, the documentary succeeds in reiterating that the United States has economic and political interests behind its banner of democracy. It also presents evidence that this imperialist repertoire has been tried before in other Latin American countries — from Cuba to Chile.

One of the documentary’s most important contributions is its attention to the collective responses to the crisis. The viewer sees the house-to-house distribution of priority foods carried out through CLAP, the government’s program, but the heart of the film is interviewing activists.

The documentary highlights the work of two cooperatives, showing members carrying out — and reflecting — on their experiences.

Cooperativa San Agustin States Convive, a grassroots organization led by women (as so much of civil society is), came together as the noose of the sanctions tightened. They reached out to a farmers’ cooperative and worked out a twice monthly market. Neighbors are welcome to join and receive the same goods at the same price.

While the CLAP bag is necessary, one activist comments, the cooperative is able to offer a variety of fruits and vegetables at a good price. Even more important, people are not just sitting around waiting for their allotment, but building something beyond capitalism or a state bureaucracy.

The documentary also highlights the work of the socialist cooperative, Altos de Lidice. Through its ties with international solidarity activists it provides medicines the government cannot obtain. Its drugstore posts prices and is open week days.

There is a tense relationship between the commune and the state. The popular organization avoids the Ministry of Health for fear of being drawn into corrupt networks.

The cooperative decided economic transparency is so important that they have instituted a monthly public accounting of expenditures. They encourage other cooperatives to adopt transparent accounting as well.

However, cooperative members realize they cannot reach beyond their community. They understand that government programs, however inadequate, can scale up in a way they cannot. One commune doctor points out that the clinics and their medical staff are part of the public health system. Although the system has deteriorated, it can be repaired.

The Role of the Sanctions

Washington’s sanctions have cut off the government’s ability to import the goods it needs. As Carlos Lazo explains, Venezuela is an oil rentier country that depends on imports for everything. The sanctions function to deepen and prolong the crisis.

However, Venezuelans Under Siege ALSO provides a critical perspective about statements that place all responsibility for the crisis on Washington. While the filmmakers highlight the imposition of U.S. sanctions, they point out that they were first imposed as the Venezuelan economy was already at the lowest point in its history.

In fact I would say that the large drop in medicine imports can be traced to the 2013-2016 period. Although Carlos Lazo explained that Venezuela is a vulnerable economy, he did not state the obvious point that this is the result of imperialism’s domination of Latin America.

When the world price in oil dropped, the Venezuelan economy went into a tailspin. Many of the social programs that were instituted under the Hugo Chavez government were threatened. Of course Venezuela isn’t the only oil-producing country that suffered, although it was clearly one of the most progressive.

The filmmakers compare Venezuela’s economic decline to that of Colombia; Colombia recovered, although modestly. They then examine the error the Madero government made by maintaining a fixed exchange rate of bolívares for dollars.

This policy enabled business to buy goods — but was in fact a subsidy to them. Maintaining this practice for years opened a gap between the official rate and the black market rate, leading to runaway inflation and corruption in both business and government. Some figures suggest inflation eventually reached one million percent.

Here are other elements to consider: a) the gasoline subsidy was a key factor in PDVSA’s downfall, b) liquidity fell 97.5% between 2011 and 2017, c) inflation was already critical before 2017, d) economic recession started in 2014, and e) by 2017, the country GDP had fallen by 30%.

What People Say

It is through interviews and examples of communities concretely dealing with their problems that the documentary provides the basis for discussing the complex situation facing the Venezuelan people. It combines data and technical background with reality on the ground.

Although the sanctions did not cause the crisis, many organizations — including the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, the IMF, Amnesty International — acknowledge the serious impact sanctions have. From this point of view, it is important to characterize the sanctions as “collective punishment” — as Jiménez Lemon and Young do. Such a practice is banned under several international law agreements.

The documentary also reveals people’s remarkable political awareness. Venezuelans know that the impact of sanctions falls mainly on people and not on government officials. One interviewee remarks, “They do not choke Maduro or Diosdado, they choke us.” It is crucial for those who see the film to understand that sanctions only suffocate those who have less.

When the filmmakers ask activists who/what is to blame for the state of the economy, answers vary. They reject U.S. intervention. Yet the rationale beyond imposing sanctions is that it will force change.

The filmmakers quote Assistant Secretary of State Lester Molloy, who in 1960 predicted an economic boycott of Cuba would bring the regime down. This immediately follows with a clip from an interview with Trump’s Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, gloating about how much Venezuelans are suffering. His assumption is that regime change would naturally follow.

Taking this into account, I certainly endorse the request of Venezuelans in the documentary to lift the sanctions. While sanctions are in place civil society organizations (which, like organized popular power, promote community solutions) have difficulties receiving and sending donations.

I also think the Left must also seriously analyze the methods through which the Maduro government is attempted to alleviate the impact of the sanctions. Gold exports have increased, which has lead to: a) an aggressive dollarization process, which harms those who only earn national currency, b) an opening of exchange control, c) elimination of price controls, d) privatization of previously nationalized companies (Cadena Éxito, Arroz del Alba SA, Tiendas CLAP), e) more flexible conditions to transnational companies, f) land restitution to old and new landlords, and h) the establishment of a dual gasoline market (one paid in dollars, the other in bolívares). Understanding these and other actions represents a big challenge.

Finally, if those who identify with some sort of Left view convince ourselves that all the blame for the Venezuelan crisis falls on the sanctions, we will be deprived of learning from past mistakes and will be destined to commit them again.

May-June 2021, ATC 212