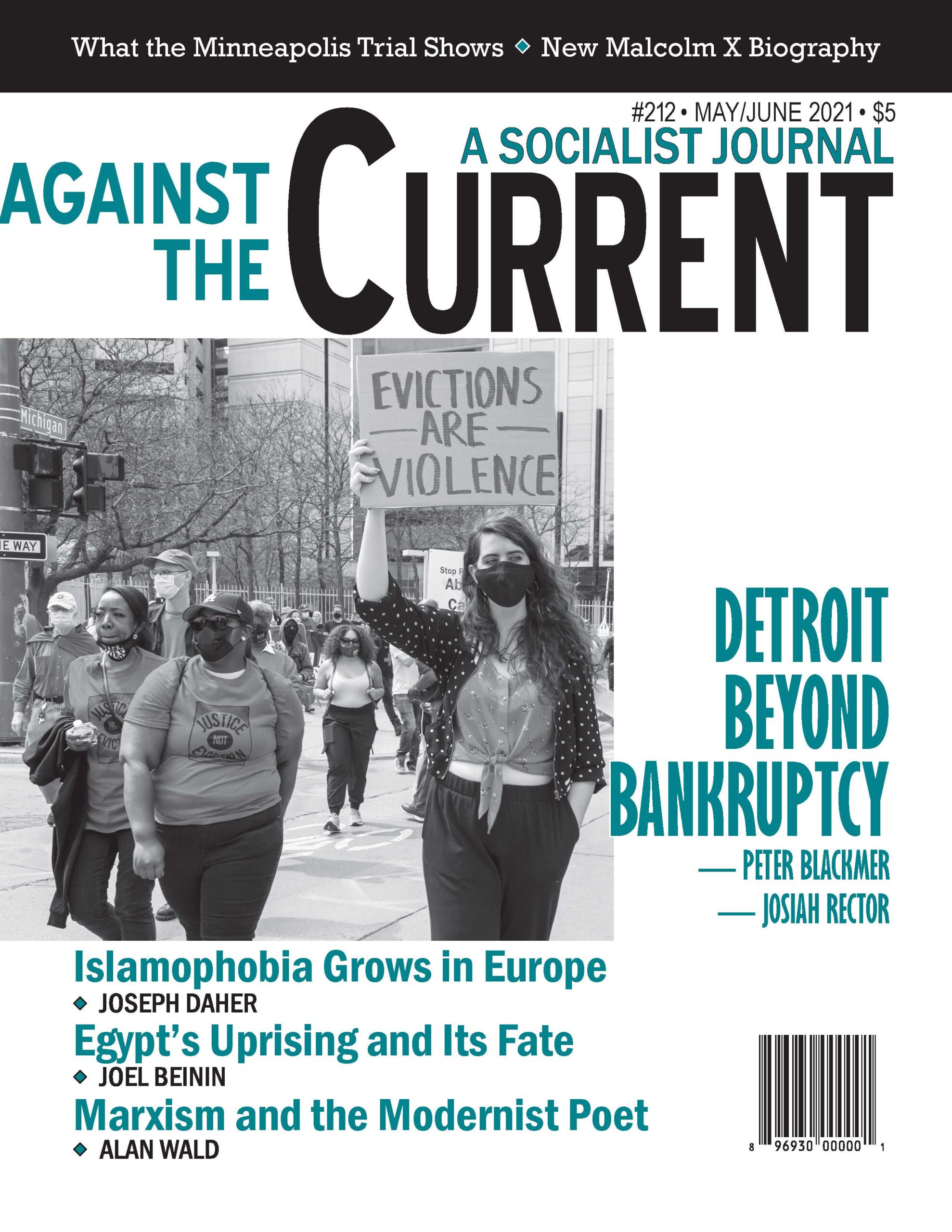

Against the Current No. 212, May/June 2021

-

Biden: "Empire Is Back"...

— The Editors -

Conviction on All Three Counts in Chauvin Trial, Bail Revoked

— Malik Miah -

Bravery, Not Blowout

— John Logan -

Egypt's Uprising and Its Fate

— Joel Beinin - Solidarity with Myanmar Peoples

-

Islamophobia in Europe

— Joseph Daher -

Marxism and the Modernist Poet

— Alan Wald -

What Method of Organizing?

— Marian Swerdlow - Tulsa's Buried Massacre, 1921-2021

- Solidarity with Kshama Sawant

- Urban Crisis

-

Detroit's Tale of Two Water Crises

— Josiah Rector -

Detroit, Comeback & Austerity: State of the City

— Peter Blackmer - Reviews

-

Bringing Malcolm to Life

— Malik Miah -

The Empire's New Forms

— Keith Gilyard -

Healing Politics -- A Doctor's Story

— Susan Steigerwalt -

Venezuela: Things Fall Apart

— Carlos G. Torrealba M. -

Danger on the Shop Floor

— Toni Gilpin -

Stirring the Dust of Archives

— Noa Saunders -

Shifting Identities in a Settler Land

— Listen Chen -

Fictionally Comprehending Trotsky

— Paul LeBlanc - In Memoriam

-

Karen Lewis, 1953-2021

— Dianne Feeley

MAY 31 AND June 1, 2021 mark the 100-year anniversary of the destruction of “Black Wall Street,” the Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma, in one of the most violent and sadistic white race riots of the bloody post-World War I period. Indeed it was pure ethnic cleansing in America.

The pretext for the assault was a trivial incident on the 31st, triggering the white Tulsa Tribune to run “an incendiary editorial under a headline residents remembered as ‘To Lynch Negroes Tonight.” Overnight, Black Tulsans mobilized what resources they had against the attacking mob. But after a 5am whistle, “By dawn, ‘machine guns were sweeping the valley with their murderous fire,’ recalled a Greenwood resident named Dimple Bush. ‘Old women and men and children were running and screaming everywhere.’” (“Remembering Tulsa: 100 Years Ago,” Tim Madigan, Smithsonian, April 2021)

In the end over 1100 homes were burned and more looted, 35 square blocks of a thriving Black community and all its infrastructure destroyed, most of its 10,000 residents left homeless, property damage guessed at somewhere between tens of millions up to 200 million dollars. The estimated number of deaths is around 300, but no one knows as bodies were thrown on trucks to be dumped, uncounted.

You can read the horrific details today, but the most incredible part of the story is the more than seven-decade coverup that followed. If you want to understand how ethnic cleansing up to and including genocide can be successfully hidden and denied, Tulsa makes for a case study.

The white perpetrators and their media said nothing, while survivors who knew the story were mostly traumatized and too terrorized to speak out — and in the long decades of lynchings, legal segregation and overt white supremacy before the Civil Rights revolution, how much of the dominant society would have believed them?

Apparently the first tear in the curtain of silence occurred in the late 1950s when a history teacher at Booker T. Washington High School told the yearbook staff how his own prom never happened because of the white mob massacre. Greeted with incredulity, the teacher began showing the photographic record, and when asked how such a thing could have remained secret, responded: “Because the killers are still in charge of this town, boy.”

It was only in 1997 that the state legislature created the Oklahoma State Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot. Tulsa native, historian John Hope Franklin, was one of its advisors. (His father, B.C. Franklin, a Black Choctaw tribal member, had been a prominent Tulsa lawyer.) The 200-page report concluded city officials were to blame — they deputized those who committed atrocities. However no one was ever convicted.

A memorial to the massacre victims stands outside the Greenwood Cultural Center, the history of the massacre is now part of the state’s curriculum and last year a team located the first group of unmarked mass graves; more have been uncovered.

Reparations for the descendants remain a critical demand in a still-segregated city where Black families are two-and-a-half times more likely to live in poverty.

May-June 2021, ATC 212</p