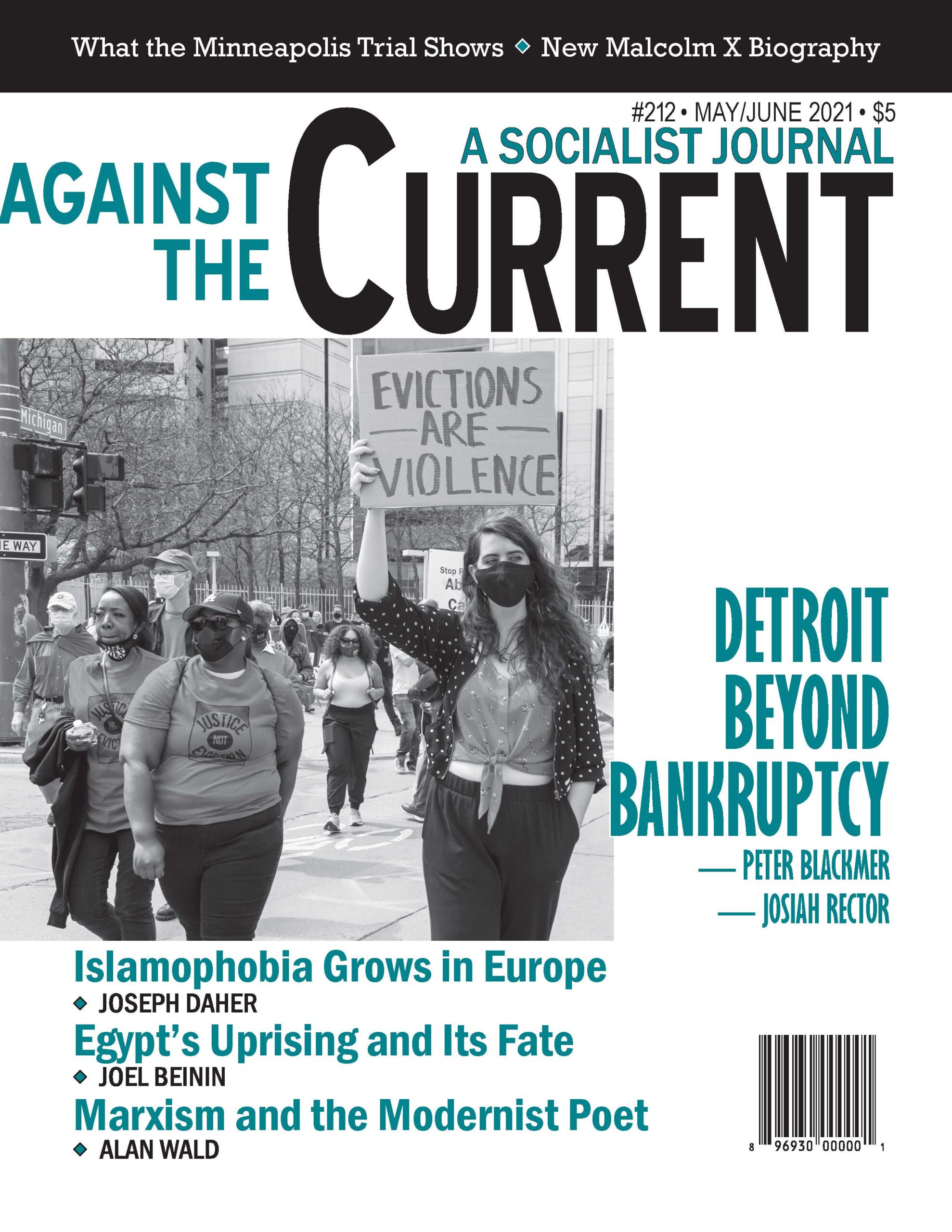

Against the Current No. 212, May/June 2021

-

Biden: "Empire Is Back"...

— The Editors -

Conviction on All Three Counts in Chauvin Trial, Bail Revoked

— Malik Miah -

Bravery, Not Blowout

— John Logan -

Egypt's Uprising and Its Fate

— Joel Beinin - Solidarity with Myanmar Peoples

-

Islamophobia in Europe

— Joseph Daher -

Marxism and the Modernist Poet

— Alan Wald -

What Method of Organizing?

— Marian Swerdlow - Tulsa's Buried Massacre, 1921-2021

- Solidarity with Kshama Sawant

- Urban Crisis

-

Detroit's Tale of Two Water Crises

— Josiah Rector -

Detroit, Comeback & Austerity: State of the City

— Peter Blackmer - Reviews

-

Bringing Malcolm to Life

— Malik Miah -

The Empire's New Forms

— Keith Gilyard -

Healing Politics -- A Doctor's Story

— Susan Steigerwalt -

Venezuela: Things Fall Apart

— Carlos G. Torrealba M. -

Danger on the Shop Floor

— Toni Gilpin -

Stirring the Dust of Archives

— Noa Saunders -

Shifting Identities in a Settler Land

— Listen Chen -

Fictionally Comprehending Trotsky

— Paul LeBlanc - In Memoriam

-

Karen Lewis, 1953-2021

— Dianne Feeley

Alan Wald

“[T]he revolution is a profession in itself, which it is the writer’s part to support as a human being, but without ceasing to be a complete writer.”—Delmore Schwartz, 1939(1)

I. Delmore Agonistes

HISTORY CAN BE a spoiler. What most students of literature are taught about the Jewish-American poet Delmore Schwartz (1913-66) is a cautionary tale of creative, reputational and psychological atrophy.

Delmore, who was almost always called by his first name, initially burst like a supernova on the Marxist literary landscape of the 1930s; a striking young eagle with a blazing movie-star charisma. As a Modernist (i.e. an author self-consciously departing from traditional ways of writing), he was dubbed “The American Auden,” extolled by T. S. Eliot and Wallace Stevens, and became a central presence in the pages of the Trotskyist-influenced journal Partisan Review.(2)

Three decades later he died at age 52; deranged, paranoid, and alone in a fleabag hotel off Times Square. A 1937 piece of surrealistic fiction, “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities,” made Delmore’s name, but the circumstances of his demise — with his unclaimed body lying for days at the Manhattan morgue — cemented his legend.

Such a finale, retold ad infinitum, has by now turned Delmore into something of a vacuous cliché: the preternaturally gifted boy genius of otherworldly innocence unable to live in a profit-driven, sordidly corrupt society; a self-destructive poète maudit in the drug-and-alcohol-addled mold of 19th century French Symbolists Arthur Rimbaud and Charles Baudelaire; or one of the English Romantic William Wordsworth’s “poets in their youth” who began in “gladness” and ended in “madness.”(3)

After the sensational behavior depicted in Saul Bellow’s biographically based novel about Delmore, Humboldt’s Gift (1975), and James Atlas’s biography Delmore Schwartz: The Life of an American Poet (1977), his saga has the aura of a life subsumed by a tabloid afterlife. One wonders if there is anything new to be said.

Then again, trumpeter Miles Davis famously observed that the notes you don’t play in jazz are more important than the ones you do.(4) Much the same can be concluded about the relative weight of what is said and not said in conventional U.S. literary history. Life stories of writers have at times been judiciously curated so as to mute the presence of a Far Left that surged multifariously in assorted (and often unexpected) cultural regions in the Great Depression, only to be beaten underground during the 1950s.

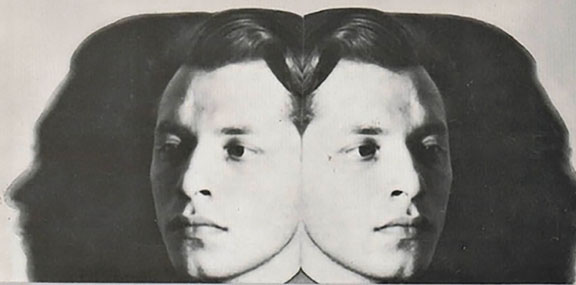

What’s customarily chronicled about Delmore in biographical and critical studies is much like a sequence of snapshots in a photo album, carefully selected for specific emphasis; inconsistent images are omitted or misleadingly captioned so as not to contest the dominant point of view as to what a bad-boy Modernist poet ought to be about.

The result is that we have inherited a kind of “body double” of Delmore, an impersonation with the political core mostly hollowed out. His career, in fact, is worthy of scrutiny precisely because it embodies the staggering political and cultural incongruities of a still-misunderstood sequence of decades.

As Michael Denning demonstrated in The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century (1996), the Depression, World War II and the postwar period was a 30-year block of time when an assortment of Marxist tendencies in art and the class struggle were in play in various guises and even disguises.

At this late date, traveling back to the old boneyard of the mid-century Literary Left to dig up and exhibit a revolutionary socialist “Comrade Delmore” feels almost ill-mannered, as if one were to brazenly dump an exhumed, rotting corpse on the table of a genteel wine and cheese reception sponsored by the Modernist Studies Association. How and why did this hasty burial of the original “political Delmore” and substitution of an anemic imitation happen, and what has been lost to cultural and radical history?

This essay is intended less as an “introduction” to Delmore Schwartz than a “reintroduction”— an effort to lay out a coherent story of Delmore’s convictions and engagements. It’s “A Tale of Two Delmores,” but not because his politics and art comprise compartmentalized strands. On the contrary, it’s for the reason that the mythic Delmore in scholarship and journalism bears little resemblance to the actually existing poet in whom these dueling constituents were distinctively if not always effectively blended together.

II. Delmore Among the Muses

Delmore was a writer and thinker who exhibited considerable range while also being irreducibly and inscrutably himself. From his teenage years he was a cultural omnivore whose eclectic interests began with French symbolism, Shakespeare, High Modernism, classical music and painting, and Greek Philosophy and Neo-Thomism; but it also extended to comics, abstract expressionism, B-movies, and baseball, as well as varieties of Bolshevism. Nevertheless, he felt at all times estranged, alienated, and apart from any national or ethnic culture.

Accordingly, the principal locus in his imaginative writing would customarily center on his own agonized psychological condition; from there he might move, usually by metaphor, to psychoanalytical, social, and historical consciousness, but most often to philosophical enigmas.

A signature poem is “The Heavy Bear Who Goes with Me” (1938), inspired by the “process philosophy” of Alfred North Whitehead, one of Delmore’s teachers at Harvard. Whitehead promoted an ontology — investigation into the nature of existence — accentuating interdependent progressions. When the stanzas open, we are presented with the human body as the foundation of experience:

The heavy bear who goes with me,

A manifold honey to smear his face,

Clumsy and lumbering here and there,

The central ton of every place,

The Hungry beating brutish one

In love with candy, anger, and sleep,

Crazy factotum, disheveling all,

Climbs the building, kicks the football,

Boxes his brother in the hate-ridden city.

As the poem evolves, we increasingly see episodes where the self-conscious writer futilely agonizes over his physical bulk and its drives that trap him in an ineluctable dilemma:

That inescapable animal walks with me,

Has followed me since the black womb held,

Moves where I move, distorting my gesture,

A caricature, a swollen shadow,

A stupid clown of the spirit’s motive….

In a fashion typical of Delmore, then, the poem has turned into a dialogue of an observing mind with itself. Somewhat like his rough contemporary, the Romanian-Jewish poet Paul Celan (1920-1970), Delmore sought to render visible those aspects of reality too often elusively indiscernible; traits to be considered not as fixed and settled but as being at issue, to be questioned.

One governing characteristic above all links this poem to much of the rest of Delmore’s writing: its mode of compulsive self-observation. Among other things, Delmore was a pioneer in the poet’s removing of the mask from one’s face to expose candid personal experiences, many of them embarrassing and self-critical.(5)

This revelatory sensibility would become the hallmark of the school of “Confessional Poetry” that blossomed in the 1950s through the work of several of Delmore’s close friends, Robert Lowell (1917-77) and John Berryman (1914-72). Naturally, since Delmore’s upbringing was Jewish, he also has a place as a pioneer in the exploration of urban immigrant culture.(6) Unlike almost all the other participants in the early Partisan Review circle, Delmore had no hesitation in aggressively coming out as Jewish. At the same time, he shared their adversity to “Jewish particularism” and offered candid, unidealized portraits of Jewish experience.

In the autobiographical verse play Shenandoah (1941), for example, Delmore agonizingly lampoons his parents’ absurd attempt to give him what they imagined to be a distinguished “Americanized” first name to balance a European (and often Jewish) last name.

In anecdotes told about his life, the poet alleged that his own unusual appellation came from “Delmore’s,” a delicatessen in his neighborhood, christened for a popular actor, Frank Delmore, who was admired by his mother; for this satire, the name “Delmore Schwartz” becomes parodied as “Shenandoah Fish.”(7)

In a passage in Shenandoah where Delmore observes himself as a child, Shenandoah looks back in wonder and pain at the forces producing his life-long sensation of estrangement from both the immigrant and prevailing mores and customs of his society:

…. you hardly know

How many world-wide powers surround you now,

And what a vicious fate prepares itself

To make of you an alien and a freak!(8)

Two years later, in what would be his major effort, the 208-page poem Genesis: Book One (1943), Delmore functioned as an anthropologist of his own Jewish immigrant family story and chronicler of the inheritance of psychological trauma that haunted him. If the final two books of Genesis had been completed, it might have been a production called, “Everything you wanted to know about Delmore’s childhood but were afraid to ask.”

In his much discussed “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities,” Delmore goes much farther by attempting a dramatic intrusion into his own past. While watching an imaginary moving picture of his parents’ engagement, he stages a disruption by standing up in the theater to protest the heartache and tragedy that will necessarily lie ahead: “‘Don’t do it. It’s not too late to change your minds, both of you. Nothing good will come of it, only remorse, hatred, scandal, and two children whose characters are monstrous.’”(9)

The Schwartz family history, which animated a number of other short stories, centers on the ill-fated marriage of his parents, Jewish-Romanian immigrants Harry and Rose Schwartz. As Harry rose to prosperity through his real estate business before World War I, the family moved to increasingly affluent neighborhoods in Brooklyn. But Harry’s philandering resulted in marital separations during the early 1920s and divorce in 1927.

Delmore escaped his unhappy family life, as well as a sense of being poles apart from his schoolmates, by declaring himself a “poet.” It was an identity that gave him a life-long sense of value, direction and dignity.

Although he was fixated on attending college and perhaps graduate school, the family’s financial fortunes were devastated by the 1929 crash and then Harry’s death the following year. Dependent on his unsympathetic mother for money, he spent 1930 at the University of Wisconsin immersed in literature and radical politics, then enrolled at New York University to study classical, analytical and contemporary philosophy with Sidney Hook, James Burnham and Philip Wheelwright.

After demonstrating brilliant potential in this field, Delmore enrolled in graduate school at Harvard where he charmed and wowed the intellectual elite, not only in philosophy but literature as well. Already he was translating Rimbaud and publishing his own poems and reviews. That’s why, in March 1937, when his financial support from Rose Schwartz ran out, he left without completing a doctorate and returned to New York City to launch a career as a fulltime writer.

In 1938 he put out his first collection, In Dreams Begin Responsibilities, with New Directions, a new independent Modernist publishing house open to Delmore and other poets on the Left. That year, age 25, he married Gertrude Buckman, a friend from high school who had also studied with Sidney Hook, who would write reviews (as well as translate exiled Bolshevik Victor Serge) for Partisan Review.

From the outset, Delmore proclaimed the Modern Masters of poetry to be his gods, but above all he aspired to be T. S. Eliot’s stylistic disciple while ignoring Eliot’s most reactionary ideas and political views. At the same time, he maintained a personal commitment to being sui generis in his themes at all costs; since he rejected the values he inherited from his family and social institutions, he believed that his poetry could provide a new vision of life and a sustenance unobtainable from any existing community.

III. Delmore’s Zig-Zag Career

As a craftsman Delmore was capable of sparkling, gem-cut perfection, not only in poetry but in literary criticism that began with writing about the Irish radical poet Louis MacNeice and the Left-wing novelist John Dos Passos, as well as the reactionary Modernist Ezra Pound.

Often he praised the very qualities that he embraced for himself, as in the opening sentences of a commentary on Rimbaud: “Beginning as a bourgeois adolescent who finds his family intolerable, Rimbaud moved with the greatest speed to a recognition of his essential enemy, the whole bourgeois culture. The age in which one exists is the air which one breathes. Rimbaud was left breathless by his age.”(10)

Yet his imaginative images could have the dreamlike intensity of surrealism and he favored the use of metaphors to give dramatic existence to ideas. In a rhymeless double sonnet based on the Socratic dialogue The Republic (514a-520a), “In the Naked Bed, In Plato’s Cave” (1938), he makes use of his own insomniac experiences to describe the delusional shadows of the night before the clarity of the day:

Strangeness grew in the motionless air. The loose

Film grayed. Shaking wagons, hooves’ waterfalls,

Sounded far off, increasing, louder and nearer.

A car coughed, starting. Morning, softly

Melting the air, lifted the half-covered chair

From underseas….(11)

Then again, for full appreciation, much of his work requires the cultivation of a specialty taste. Now and again there are verses so encrypted as to require an Enigma Code-breaking machine for comprehension. “Concerning the Synthetic Unity of Apperception,” taking its theme from René Descartes, begins:

“Trash, trash!” the king my uncle said,

“The spirit’s smoke and weak as smoke ascends.

“Sit in the sun and not among the dead,

“Eat oranges! Pish tosh the car attends.”(12)

The linguistic play may be intriguing but trying to explicate too much of this can make one’s eyes cross over.

Delmore also wrote many dialogues and blank verse dramas such as “Choosing Company” (1936), “Dr. Bergen’s Belief” (1937), and “Paris and Helen” (1941). In “Coriolanus and His Mother” (1938), a Delmore-like narrator observes a dramatic performance of the story of the legendary Roman leader in the company of Marx, Freud, Aristotle and Beethoven; between the acts he jumps onto the stage to provide commentary. These are relatively straightforward entertainments but not exactly heart-pounding narratives; it is likely that most present-day readers will require time and study for maximum gratification.

In fact, except for a dozen or so of his best-known pieces of poetry, fiction and dialogue distinctive for their lucidity, reading Delmore in the absence of some degree of background knowledge in philosophy and the classics may seem at times like a recipe for masochism. That’s why his career was never as a popular writer nor lucrative.

Fortunately, he had a talent for making a favorable impression on exceptional people who assisted him as protectors, in publishing and promoting his work. Since he didn’t have a Ph. D. and was Jewish at a time when few Jews were accepted in English Departments, these allies worked to obtain temporary teaching positions for Delmore at leading institutions.

Nevertheless, the events of his personal life and the ups and downs of his career combined with deepening psychological problems and a dependency on drink and drugs to make the next 25 years a zig-zag affair. He would hold the high ground in Parnassus for a certain time, but then his fame and reputation would unhappen. Editorial positions didn’t last, and teaching positions became more difficult to sustain as word of his erratic behavior circulated. His final chapters are a long and painful saga.

Delmore’s first marriage ended after six years, and a second, to novelist Elizabeth Pollet in 1949, didn’t survive much longer. In 1940 he received an appointment as a composition instructor at Harvard, followed by a Guggenheim Fellowship, but poor reviews of Shenandoah and Genesis were personally devastating. As his life began to go off the rails he quit Harvard and moved to a number of universities but failed to secure a lasting position.

Even though he continued to produce fresh material in private, much remained in draft form and his new books often involved reordering, re-titling and reprinting earlier work. An award of the prestigious Bollingen Prize for Poetry in 1959 brought Delmore some momentary new attention, but his diet of barbiturates and amphetamines were taking their toll. He inspired one of his students, the Velvet Underground guitarist Lou Reed, to write, but almost all his old friends became targets of demented conspiracy theories.(13)

Repeatedly committed to New York’s Bellevue Hospital for psychiatric care, he resisted treatment and moved among dilapidated hotels in the city until dying of a heart attack on an elevator while taking out his trash in the middle of the night in July 1966.

IV. Political Delmore

To paraphrase Tennyson, in the spring of Revolution a young person’s fancy turns to Bolshevism. That’s certainly the way it was for Delmore, and many of the best and the brightest of his generation in the early 1930s. Capitalism was in crisis, memories of the international slaughter of World War I were only a decade in the past, and the Soviet Union was still the youthful experiment of idealists that deserved the benefit of the doubt.

There should be no haziness as to where Delmore’s convictions lay in “The Red Decade,” especially when he affiliated with Partisan Review. In spite of that, existing scholarship and journalism take a fast-food approach to his political ideology, often combined with a surfeit of misapprehensions about Marxism and the literary Left.(14)

Ceaselessly we are borne back to the era of Great Depression radicalism, but it changes every time a new generation looks at it. Nowadays, if Communism is mentioned in relation to Delmore, it is mainly in terms of describing the poet and Partisan Review as “anti-Communist”— barely suggesting what they were for.

Political labels should be used to open up and enlighten, not box in and evoke stereotypical bias. To clarify, one might employ a capital “C” Communism to indicate official pro-Soviet Communism, which by the 1930s was often called “Stalinism” by both supporters and radical opponents. In contrast, small “c” communism could indicate the heretical forms of Leninism, Bolshevism, council communism, and revolutionary Marxism to which Delmore and many others were attracted.

For the pre-World War II Partisan Review, which was launched by the Communist-led John Reed Club in 1934 but became organizationally independent in 1937, the more correct and illuminating political characterization should be “communist anti-Communist” or “communist anti-Stalinist.” Of course, among the heretical Leninisms of the time, the politics of Partisan Review were certainly closest to Trotskyism, but the editors refrained from using the term because they did not want their journal to be linked to any specific political organization.

In any event, for a contemporary audience, especially after the distorting prism of the Cold War has done its work, describing Delmore and the journal as simply “anti-Communist” without context or qualification doesn’t do it. A fact-based argument about this must begin with documentation, of which there is plenty.

One premier exhibit is the letter (now published) that journalist Dwight Macdonald sent in August 1937 to Leon Trotsky on behalf of the newly-formed Partisan Review editorial board: “all of us are … committed to a Leninist program of action. We believe in the need for a new party to take the place of the corrupted Comintern.”(15)

In February 1938, the editors publicly elaborated this stance: “Our program is the program of Marxism, which in general terms means being for the revolutionary overthrow of capitalist society, for a workers government, and for international socialism. In contemporary terms it implies the struggle against capitalism in all its modern guises and disguises, including bourgeois democracy, fascism, and reformism (social democracy, Stalinism).”(16)

Note that opposition to Stalinism was still far from the main political concern of the journal; affirming the abolition of capitalism was its central point. Stalinism is placed in a subsidiary position as a subset of reformism equivalent to social democracy. This was because the 1935 Popular Front had reoriented Communist parties to an alliance with “democratic” capitalist countries based on a preservation of their existing social order.

Delmore, whose writing appeared as the first item in the first issue of the revamped publication, personified Partisan Review’s politico-cultural ethos. “If any writer could be singled out as the most extreme representative of the new intellectual grouping,” recalled founding editor William Phillips, “it would be Delmore Schwartz” who embodied “most of the strains that came together in that period.”(17)

None of this is to suggest that Delmore was your average Bolshevik-Leninist, at least as judged by what was required for membership in most vanguard groups. His own relation to Marxism would be qualified by an insistence on eschewing all self-descriptions but that of poet, and he habitually preferred to evade any kind branding or labeling for himself, unless ironic.(18)

For the most part, Delmore-as-Marxist surely recalls German-Jewish cultural critic Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) — steeped in philosophy and high culture, intensely interested in the materials of daily life, refusing to spurn notions of the need for God and the value of religious traditions, and with his back to the future. Delmore was also resistant to utopian notions of fundamental changes in the human character, despite Marxism’s accuracy in analyzing social formations.

On the other hand, the idea that Delmore wasn’t “political” is absurd. The most conspicuous purveyor of this myth was journalist and former Trotskyist Dwight Macdonald, who penned an obituary for Delmore announced on the front page of The New York Review of Books.(19) If one had wanted to intentionally design a strategy to misrepresent Delmore’s relation to politics, one could not do better than what Macdonald managed to accomplish.

When biographer James Atlas came along to write his acclaimed Delmore Schwartz: The Life of an American Poet, Macdonald not only served as eminence grise, but read over and edited every page of the manuscript before bestowing his blessings on the final product.(20) What Macdonald claimed about Delmore’s politics was brief: “Delmore’s was a remarkably reasonable mind, immune to the passions and prejudices of our period [the 1930s-50s]. He was not a joiner….he seemed to feel no need for any political commitment as a writer, at least I can’t recall his signing any of my manifestos or joining any of my committees.”(21)

There are times when one feels the need to go up on the roof and shout in protest, and this is one of them.(22) All Macdonald had to do was meander over to his bookshelf and pull out the early issues of Partisan Review that he edited. Delmore’s name appears on every statement issued by the League for Cultural Freedom and Socialism (LCFS),(23) the U.S. branch of the International Federation of Revolutionary Art announced by Trotsky, André Breton and the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera.

The LCFS was the first and most significant of the committees Macdonald initiated, and where he served as secretary. Additionally, Delmore’s name appears among the founding signatories of the 1946 “Europe-America Group,” the second most important of Macdonald’s committees, whose signers sought a post-war dialogue among radicals.(24) If there are additional initiatives that Macdonald formed and Delmore rejected, I am unaware of them.

Asking no questions, Atlas and all other writers about Delmore have omitted these references. Atlas also provided the grotesquely assured conclusion that Delmore was “Always apolitical.”(25) This has served as a permission structure for numerous others to avoid serious consideration of Delmore’s heartfelt convictions.

Macdonald is also way off in insisting that Delmore was “immune” to the political passions of his time. If one departs from what has been published directly on Delmore and reads around in the general history of the Cultural Left, one learns that pro-Communist composer Marc Blitzstein and Delmore nearly exchanged blows over the Hitler Stalin Pact while at the Yaddo artists’ colony in 1939.(26)

One also discovers that Delmore intervened on political grounds to prevent New Directions Publishers from bringing out Kenneth Patchen’s remarkable The Journey of Albion Moonlight (1941).(27) The pages of Partisan show that Delmore published a brutal denunciation of Muriel Rukeyser because her wartime poems had switched to a pro-Allies position.(28) And Delmore himself confessed that he became “violent and emphatic”(29) when addressing writers with whom he politically disagreed.

Macdonald’s “not a joiner” line certainly gives a hyperbolic assessment of Delmore’s undeniable detachment from political organizations that belies his frequent status as an ally. As a University of Wisconsin student, Delmore first read Marx under the tutelage of the leader of the Young Communist League, and efforts to recruit him continued when he returned to New York.(30)

While at New York University he was part of a group of members and close sympathizers of the Trotskyist movement who met in James Burnham’s apartment.(31) In 1934 he co-edited a Marxist literary journal called Mosaic, and while at Harvard his close mentors included Communist fellow-travelers F.O. Matthiessen and D.H. Prall. In July 1936 he appeared with mostly pro-Communist poets in a special “Social Poets Number” of Poetry magazine edited by Horace Gregory, about to be appointed Contributing Editor of the New Masses.(32)

In 1937 Delmore published in the Marxist Quarterly, which only gets mentioned as an item on his bibliography but almost certainly occurred as a consequence of his significant associations with the Trotskyist movement. In fact, in 1938 the poet John Wheelwright, a member of the Socialist Workers Party in Boston, wrote to James Burnham, now editor of its theoretical journal New International, that Delmore was a party sympathizer who ought to be asked to contribute.33

In March 1939 Delmore taught at the Socialist Workers Party’s “Marxist School” along with leading Trotskyist thinkers such as Max Shachtman and Burnham.(34) In May 1940 Delmore praised the new newspaper of the Workers Party (the breakaway from the Socialist Workers Party led by Max Shachtman) and took out a subscription to Labor Action.(35)

This list of associations, almost all of which are simply excluded from scholarship on Delmore, palpably doesn’t match that of young revolutionary firebrands of the time, such as Nathan Gould and Myra Weiss; but neither is it the profile of cold aloofness from the Left suggested by Macdonald.

V. Delmore, the Complete Writer

In parallel fashion, explicit Marxist political statements by Delmore in his essays have been omitted from scholarship and mostly excluded from anthologies.

In 1938, when he published his Southern Review essay on Dos Passos, he included a favorable discussion of the Hungarian Marxist Georg Lukács’ writing, based on what had appeared in the Communist journal International Literature. This was among the very earliest considerations of Lukács in the United States, and along with Delmore’s Marxist Quarterly contribution (elaborating on Columbia University art historian Meyer Schapiro’s views), puts him in proximity to what is now called “Western Marxism.”(36)

In 1943 Sidney Hook published The Hero in History, and Delmore wrote a fine review rejecting outright Hook’s claim that “Lenin’s revolution is the chief cause of the world depression, the annihilation of the European labor movement, the coming to power of Hitler, and the Second World War.”

His rebuttal relied on his study of Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution and Delmore kept his focus on capitalism as the source of war and fascism. “Surely the chief causes [of depression and World War II],” Delmore concludes, “ are the conditions of international capitalism, the very causes which brought about the first war in 1914.”(37)

In 1955 in the New Republic, Delmore insisted in an article about the cartoon version of George Orwell’s Animal Farm that the Bolshevik project in 1917 had been “the greatest and best social hope of human beings converted into a cynical despotism…its leaders and supporters were for the most part not gangsters and careerists, but dedicated martyred heroes and millions of men of good will.”(38)

This blunt statement was likely a case of Delmore thumbing his nose at the view predominant among Cold War liberal anticommunists, which was that a fascist-like totalitarianism had sprung directly from the ideas of Lenin.

Elsewhere, Dwight Macdonald provides a characterization of Delmore’s view of World War II that makes me want to haul him before a Truth and Memory Commission. Partisan Review and the League for Cultural Freedom and Socialism were founded on the belief that the U.S. entrance into an international war would not be to preserve democracy but continue the same struggle for the dominance of world markets that had produced World War I.

They believed that capitalism was the incubator of fascism and that fascism could not be militarily defeated without a socialist transformation. While some participants in the Partisan Review circle began to back away from this analysis with the start of the war, Delmore and Macdonald were among those who resisted.

Nevertheless, in a 1979 interview Macdonald was asked about Delmore’s “position” on World War II and replied: “He had no position.” The interviewer, perhaps sensing that this didn’t seem quite right, asks again, “He had no position about things?” and Macdonald insists “No, none whatever.”(39)

In fact, Macdonald had sent correspondence to Delmore in 1942 demanding that he make public in the pages of Partisan Review the strong antiwar opinions he acknowledged in personal conversation, suggesting that Delmore emulate the anarchist Paul Goodman who had openly promoted draft resistance.(40)

A few weeks later Delmore replied that he wasn’t going to advocate doing anything about the war because it was a meaningless gesture under current conditions to directly propose any particular action to hinder it. The role of the intellectuals was simply to defend “culture and truth,” which meant pursuing one’s art but also detailed and constant criticism of the war.(41)

At this time, Delmore was in the process of officially joining the editorial board of Partisan Review, which Macdonald had quit in protest of the journal’s refusal to continue outright opposition to the war. So Delmore’s letter, combined with his failure to publish any substantial disapproval of the war, has elements of opportunism.

This corresponds to the memory of Sidney Hook: “I got the impression at that time that he [Delmore] valued his association with Partisan Review more than he did his qualified agreement with Macdonald. Delmore was always more concerned with himself and his position on the firmament of poetry than with anything else.”(42) Hook also adds about Delmore: “He fancied himself as not only a poet but as a man of the world and a realistic political analyst….”(43)

Correspondence at the same time from Delmore to playwright Robert H. Hivnor (1905-2005) elaborates his stance in light of maintaining one’s creative writing: “you must keep yourself going and living as a writer, no matter what demands the new war and the entelechy [from Aristotle, vital function] of revolution make upon you. By an uneven analogy, the writer is like the doctor and the shoemaker, and only by being a doctor and a shoemaker can he do any good.”

On the question of one’s individual relation to the Marxist political movement, Delmore was precise: “the revolution is a profession in itself, which it is the writer’s part to support as a human being, but without ceasing to be a complete writer.”(44)

VI. Et Tu, Delmore?

From the time of the Partisan Review’s renovation in 1937, Delmore and the editors argued vigorously for the strategic autonomy of the publication; this was against the demand of the Socialist Workers Party for closer affiliation.(45) After all, if a journal is to focus on the creative arts, there is simply no benefit from a formal affiliation to a full political program or party, and plenty of risk.

Yet Partisan Review was political and did take positions. Ultimately its independence was surely compromised as it aligned with Cold War anticommunism. The editors may have continued to consider themselves Marxists, but the goalposts defining their radicalism had moved so far that one might as well call them SINOs — Socialists in Name Only.

While warning signs were coming into view as World War II progressed, a turning point occurred with their publishing in the summer of 1946 an editorial called “The Liberal Fifth Column,” demanding a more confrontational foreign policy toward the USSR.(46) Drafted by Delmore’s close friend philosopher William Barrett but endorsed by all the editors, the text dangerously promoted outrage against liberals seeking to avoid a Cold War if not a hot one.

From that point on the Partisan Review editors were navigating dangerous waters, correctly recognizing a new world situation that demanded the abandonment of old dogmas but forsaking what was still worthwhile in the revolutionary socialist perspective. In effect, they were living the deed of apostasy before committing themselves to its performance.

In only a few more years they would become the recipient of cash from the CIA-funded American Committee for Cultural Freedom, showing a political convergence sometimes called “State Department Socialism.” After that, their reputation on the Left was permanently besmirched; any memories of the inspirational independent Marxists they had once been were now abandoned as mortified ghosts trapped in a world from which there was no salvation.

Delmore too was politically bound in a straitjacket of his own fashioning. For too long he had been contending with his own ambiguous motivations, struggling to align the contradictory pieces of his identity. Under the excruciating conditions of the Cold War, he simply couldn’t survive their inevitable collision.

He may have sometimes claimed that his views hadn’t changed but his name was now prominent on the letterhead of the American Committee for Cultural Freedom, a grim voice of anti-communist liberalism (e.g. opposition to not just Communism but all varieties of communism — and wimpy about McCarthyism).

Still, there was little sign of any recorded activity. For the most part, when it comes to addressing anything other than literature, there is something blurry about Delmore in the 1950s, like the figure in the background of an old photograph. The political plot doesn’t thicken so much as dissolve.

Perhaps he resisted what was known as “The Age of Conformity” through his insistence on his alienation and the inability of American culture to address the true needs of the artist. In a famous symposium on “Our Country and Our Culture,” he was distinguished by a negative note: “the highest values of art, thought, and the spirit are not only not supported by the ways of modern society, but they are attacked, denied, or ignored by society as a mass.”(47)

Delmore’s most notable political intervention in that decade seems to have been his 1953 Partisan Review essay about Columbia University English professor Lionel Trilling, “The Duchess’ Red Shoes.”(48) There is strong evidence that this was a critical foray designed to create some distance between the journal and the ideas of Trilling. In the eyes of several of the editors and writers, Trilling, part of the original Partisan Review milieu, was regarded as moving to the Right too precipitously, and Delmore thought that his repugnant politics would become more obvious if separated out from his mandarin literary views.(49)

The exchange has now earned a minor place in literary history. That’s because, whatever his new drift, Trilling was always a compelling, rich and complex thinker; and Delmore was a powerful intellectual match who went in for the kill, pointing to signs of intellectual snobbery with dialectical finesse. Nevertheless, so far as politics goes, revolutionary socialists had far more pressing matters on their minds at the height of McCarthyism and the Korean War than to parse just how much farther Trilling was to the Right than others among the New York Intellectuals.

VII. Delmore’s Internationalism

The point is that the tectonic cultural shift after World War II changed everything in regard to short-term prospects for revolutionary transformation in the United States. And 75 years after that, so much more has happened in our culture and politics that one can have a hard time wrapping one’s mind around Delmore’s actual achievement even if we now factor in his political life.

Most of all, clarity is needed about his blend of Marxism with High Modernism, which can easily scramble readers’ expectations. For example, many socialists, myself included, customarily think of politics and poetry in terms of a scintillating agitational work, such as Claude McKay’s response to the “Red Summer” of 1919 in “If We Must Die,” or of eloquent commemorations of historical events, such as W. B. Yeats’ eulogy of the Irish nationalist uprising against British rule in “Easter 1916.” Delmore’s work, in contrast, is often highly political without being written for a political purpose.

Among his paramount concerns as an artist was to root the personal in an international perspective. This did not begin with politics but with his view of poetry as an epistemological endeavor — an effort to acquire knowledge of who he was, which he might clarify by his own writing. Along with his search for new poetic forms and idioms appropriate to the modern world, the initial attraction was a perceived cosmopolitanism in James Joyce and T. S. Eliot.

When Delmore first began to read Trotsky, starting with Literature and Revolution (1922), while at the University of Wisconsin, he began to see the Russian Revolution as paramount among the world-shaping factors of his time. Such a perception became the basis of one of his most successful poems, “The Ballad of the Children of the Czar” (1937). In rapidly moving unrhymed couplets, he links his own situation as a two-year-old child in Brooklyn to the children of Czar Nicholas at the same time:

The children of the Czar

Played with a bouncing ball

In the May morning, in the Czar’s garden,

Tossing it back and forth….

While I ate a baked potato,

Six thousand miles apart,

In Brooklyn, in 1916,

Aged two, irrational.

The standpoint he dramatizes on the fatal connections among the personal, historical, and social in 1914, are likely inflected by passages about Alexander II, father of Nicholas, from Chapter 6 of Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution (English translation, 1932).(50) The politicization of history comes in lines that show all of us variously as the casualties of history:

The shattering sun fell down

Like swords upon their play,

Moving eastward among the stars

Toward February and October.(51)

“The Ghosts of James and Pierce in Harvard Yard” (1938) is a more recondite, philosophically inspired sonnet, dedicated to the memory of his Harvard teacher D.H. Prall. Delmore depicts “a waking dream” in which the two “fathers of pragmatism” (William James and Charles Pierce) voice a cryptic warning about the state of the world as international war looms ahead:

We studied the radiant sun, the star’s pure seed:

Darkness is infinite! The blind can see

Hatred’s necessity and love’s grave need

Now the poor are murdered across the sea,

And you are ignorant, who hear the bell;

Ignorant, you walk between heaven and hell.(52)

Often Delmore’s more Kafkaesque stories seem to have political dimensions. These include his early prize-winning “The Statues” (1938) and late “The Track Meet” (1959). Both feature a vulnerable and decent individual caught up in a situation he barely understands, very much in the mode of Kafka’s The Trial (1925) and The Castle (1926). In both cases the narrators are struggling to influence the world around them, each man marked by a kind of intelligence and hyperconsciousness that sets him apart from others. The configuration of the first story strongly suggests life before World War II and the second a postwar sensibility.(53)

Politics is at its most straightforward in Delmore’s fiction and poetry of the postwar moment itself. “A Bitter Farce” (1946) depicts a wartime writing instructor assigned to two classes. One consists of young soldiers, obviously pro-war and filled with racist sentiments especially produced by the recent (1943) Detroit race riot targeting African Americans. The title, “A Bitter Farce,” is apt, to describe the embarrassing behavior of the instructor in his effort to balance survival with dignity.

The similar leitmotif of frustration is present in the second section of his collection Vaudeville for a Princess and Other Poems (1950), “The True, the Good, and the Beautiful.” This phrase almost certainly stands for the traditional ideals of the poetic vocation, to which Delmore had a profound loyalty. Six of the poems are explicitly addressed to “Dear Citizens,” indicating that he is talking to the society at large in an attempt to vindicate his recent behavior during the war.

In the body of the poems, the poet explains that he feels charged with the irresponsible behavior of being a mere bystander to the war of the past four years. His response remains that he has been dedicated to poetry, but he can’t help wondering if his non-action might have been more like a prostitution.

VIII. Delmore in Our Time

Delmore Schwartz’s legacy no doubt appears as a revolutionary commitment mired in ambiguity. Those trying to analyze his motives are invariably left with intractable questions. Only with great effort and research can his imaginative writings offer a window into his psyche, and even that is far from an unfiltered pipeline into true motives. In the meantime, the political and cultural achievement of Partisan Review — once the go-to place for Franz Kafka, Victor Serge, Karl Korsch and many more — has faded from public memory.

A restoration of Delmore in the socialist cultural tradition was never going to be an easy sell, especially for those who prefer biographies of revolutionary socialist ancestors to read like chapters from a socialist version of Lives of the Saints.

Delmore’s was a beyond-problematic life, a combination of extraordinary talent and self-destructive actions, which not only involved drugs but also cringeworthy stories about predatory sexual behavior. There were also emotional imperfections, including racial and gender myopia, as well as failures in empathy and understanding.

Finally, one must acknowledge that the world that formed Delmore’s anti-capitalist and socialist consciousness has changed almost beyond recognition. Especially obsolete and hard to fathom are the Marxist predictions for short-term social transformation; in light of their failure to materialize, the politics advocated by Delmore may seem like self-delusionary fantasy.

Few things look more dated than yesterday’s idea of tomorrow. All this is made even less attractive by proclamations in the Trotskyist press and Partisan Review animated by an overkill of high passion and moral certainty, combined with much sneering at the supposed intellectual vacuity of political foes. Extreme conditions can push those who dream of socialist egalitarianism to intemperate extravagances.

Without dismissing such caveats, fundamental issues that riled Delmore still whisper to us across the decades: economic and racial discrimination, the dangerous intensification of a domestic and international Far Right, the failures and hypocrisy of liberalism, and the incapacity of a revolutionary left to cohere and win a majority of the working class.

Moreover, no matter what he wrote, Delmore was always conscious of the costs of capitalist society, even when his social vision in his last years seems elliptical and buried. All the same, we remember him because, as a sympathizer, he tried to inhabit the fraught political space of independent revolutionary socialism between the violent and aggressive power blocks of his era. As a thinker, in his own time he demanded and practiced a non-reductive Marxism. In the best of the early Partisan Review tradition, he aimed to infuse creative writing as well as criticism with social and historical dimensions without fetishizing any particular forms as progressive or reactionary.

History is always selective in how it tells deeply complicated narratives. Nonetheless, the arrhythmic heart of the matter is that we have two stories about the life and work of Delmore from which to choose. They contradict each other, and the first one lets you feel OK about skipping the knotty political debates that were central to the literary Left in the 1930s.

The other, however, stands hidden in plain sight in a brief early flashback to the young Von Humboldt Fleisher (largely a stand-in for Delmore) in Bellow’s Humboldt’s Gift: “Then and there I realized that if I didn’t read Trotsky at once I wouldn’t be worth conversing with. Humboldt talked to me about Zinoviev, Kamenev, Bukharin, the Smolny Institute, the Shakhty engineers, the Moscow Trials, Sidney Hook’s From Hegel to Marx, Lenin’s State and Revolution. In fact, he compared himself to Lenin.”(54)

The way one understands the past inevitably explains how one understands the present, and this strange amnesia about the political Delmore is symptomatic of the challenges we face in reconstructing the still-buried history of aspects of the Far Left in order to grapple with our own possibilities and constraints.

The example of Delmore as socialist and poet once again illustrates that few intellectual problems are more fraughtful than confronting the intricate symbiosis between politics and art. Then, when it comes to projecting a future course of action, the many miscalculations of the 1930s show that there always needs to be space for the unsure, the tentative, the maybe.

Finally, in our work ahead to create a culture of solidarity, activists and scholars are going to have to come to terms with understanding that anyone’s commitment at any time may not be easily understood through litmus tests and static categories. As with Delmore, it is rare that a writer can be consigned to a stationary spot along the political spectrum.

Notes

- Delmore Schwartz to Robert Hivnor, Robert Phillips, ed., Letters of Delmore Schwartz (Princeton: Ontario Review Press, 1984), 75.

back to text - These accolades are cited in many places, including: https://conchapman.wordpress.com/2017/07/22/homage-to-delmore-schwartz-2/

back to text - From The Prelude, an autobiographical poem published posthumously in 1850.

back to text - The frequently cited statement is, “It’s not the notes you play, it’s the notes you don’t play.” See: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/02/arts/music/silence-classical-music.html

back to text - A brilliant study of this aspect can be found in the discussion of Delmore in Adam Kirsch, The Wounded Surgeon: Confession and Transformation of Six American Poets (2005).

back to text - In The Nation, June 22-29, 2015, Vivian Gornick makes the case for the revival of Delmore as a major Jewish poet: https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/delmores-way/. A fascinating statement of Delmore’s attitude toward his Jewish identity appeared in the symposium “Under Forty” in Contemporary Jewish Record (February 1944): 12-14. It was recently reprinted for the first time in Ben Mazer, ed., The Uncollected Delmore Schwartz (2019).

back to text - The delicatessen story seems as bit off — as the only reference to “Frank Delmore” that I can find is a fictional character in a 1925 film played by actor Wheeler Oakman.

back to text - From “Shenandoah,” reprinted in Craig Morgan Teicher, Once and For All: The Best of Delmore Schwartz (New York: New Directions, 2016), 202.

back to text - Delmore Schwartz, In Dreams Begin Responsibilities and Other Stories, ed., with an Introduction by James Atlas (New York: New Directions, 1978), 8. Delmore had a younger brother, Kenneth.

back to text - Delmore Schwartz, “Rimbaud in Our Time,” Poetry 55 (December 1939): 148-54.

back to text - Delmore Schwartz, “In the Naked Bed, in Plato’s Cave,” Selected Poems, 25.

back to text - Delmore Schwartz, “Concerning the Synthetic Unity of Apperception,” Selected Poems (New York: New Directions, 1959), 40.

back to text - On Lou Reed and Delmore see: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/articles/69810/o-delmore-how-i-miss-you

back to text - The only exception is a terrific pithy monograph by Alex Runchman, Delmore Schwartz: A Critical Reassessment (2014), which discusses his response to World War II, albeit from a different perspective than I offer. To my knowledge, there was only one review of this book.

back to text - Letter from Dwight Macdonald to Leon Trotsky, 23 August 1937, in Michael Wreszin, The Letters of Dwight Macdonald (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2001), 93-94.

back to text - “Politics and Partisan Review,” Partisan Review 4, no, 3 (February 1938): 38.

back to text - William Phillips, A Partisan View: Five Decades of the Literary Life (New York: Stein and Day, 1983), 75.

back to text - A number of critics cite Delmore’s one statement in a letter to Trotskyist Julian Symons that “I am not, by the way, a Marxist,” ignoring that his objection to the alleged causality of the base-superstructure model is akin to that of Raymond Williams and other Western Marxists: “Marx seems to me to have discovered all the connections — what is wrong is the causal direction, first productive relation, then value….” See Letters of Delmore Schwartz, op. cit., 65.

back to text - The text was subsequently reprinted as an introduction to the Selected Essays of Delmore Schwartz (1970) and over the years cited with frequency.

back to text - This is documented at length in James Atlas, The Shadow in the Garden: A Biographer’s Tale (New York: Pantheon, 2017), 135-44.

back to text - Dwight Macdonald, “Delmore Schwartz (1913-1965),” The New York Review of Books, 8 September 1966, reprinted in Donald A. Dike and David H. Zucker, eds., Selected Essays of Delmore Schwartz (Chicago: University Chicago Press, 1970), xv-xxi.

back to text - Why Macdonald so drastically misrepresented Delmore’s politics is a complex matter. One part of the answer lies in the reluctance of once-revolutionary activists who later gained prominence to return to complicated older debates that would require considerable patience and knowledge to understand — such as the raison d’être of the League for Cultural Freedom and Socialism, to which Macdonald never seems to have referred after the 1930s. Another is Macdonald’s habit of declaring intellectuals who failed to agree with his aggressive stance as less political. See the discussion of Macdonald’s break with Partisan Review in Michael Wreszin, A Rebel in Defense of Tradition: The Life and Politics of Dwight Macdonald (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 123.

back to text - See “War is the Issue,” Partisan Review VI, 5 (Fall 1939): 128-30.

back to text - “The Manifesto of the Europe-American Groups,” from the Dwight Macdonald Papers at Yale University, is reproduced as a photocopy in Cavoulacos, Sophie, “A Quixote in the American Century: Dwight Macdonald and the Politics of Imagination,” 2008-2010 Penn Humanities Forum on Connections, 88.

back to text - Moreover, if one looked through issues of the Socialist Appeal, one would see Delmore’s name as a member of the group in an article starting on page 1 of the 6 June 1939 issue. This publication is now on-line: https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/themilitant/socialist-appeal-1939/v3n39-jun-06-1939.pdf

back to text - Eric Gordon, Mark the Music: The Life and Work of Marc Blitzstein (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989), 180.

back to text - See discussion at: https://www.nyjournalofbooks.com/book-review/journal-albion

back to text - See David Bergman, “Ajanta and the Rukeyser Imbroglio,” American Literary History, 22, Issue 3 (Fall 2010): 553–583.

back to text - Phillips, Letters of Delmore Schwartz, op. cit., 104.

back to text - Maurice Zolotow “I Brake for Delmore: Portrait of the Artist as a Young Liar,” Michigan Quarterly Review 25, No. 1, available at: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/mqrarchive/act2080.0025.001/8:2?rgn=main;view=image. At the time I wrote The New York Intellectuals (1987) I was unaware of this information and assumed that Delmore had not been interested in politics during his year at the University of Wisconsin.

back to text - E-mail from Eric Poulos to Alan Wald, 8 September 2020, in reference to his mother’s memory of Delmore Schwartz. Ruth Ageloff Poulos (party name “Ruth Sawyer”) was an early Trotskyist who was in an English class with Delmore as well as participant with him in a group of Trotskyist students and close sympathizers that met at Burnham’s apartment. She assumed that Delmore was a member of the organization and described him as a “comrade.”

back to text - See “Social Poets Number,” Poetry: A Magazine of Verse XLVII, No. II (July 1936).

back to text - John Wheelwright to James Burnham, 12 July 1939, Brown University Collection.

back to text - Advertisements for Delmore teaching a class at the Marxist School, which was a collaboration between the Partisan Review and Socialist Workers Party, appeared in February and March 1939 issues of Socialist Appeal. See, for example, “Marxist School will Open February 27,” Socialist Appeal 3, no. 5 (4 February 1939), 3.

back to text - Phillips, Letters of Delmore Schwartz, op cit., 98.

back to text - Delmore Schwartz, “John Dos Passos and the Whole Truth,” Southern Review 4, 2 (1938): 351-67. It was reprinted in Donald H. Dike and David H. Zucker, eds., Selected Essays of Delmore Schwartz (1970). Delmore’s Marxism was very close to that of Schapiro, who can certainly be identified with a U.S. counterpart to Western Marxism.

back to text - Delmore Schwartz, “The Hero in Russia,” Kenyon Review 6, no. 1 (Winter 1944): 126-129.

back to text - “Films,” New Republic, 17 January 1955, 22-23.

back to text - Michael Wreszin, ed., Interviews with Dwight Macdonald (Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2003), 126.

back to text - Dwight Macdonald to Delmore Schwartz, op. cit, 109.

back to text - Robert Phillips, ed., Letters of Delmore Schwartz (Princeton: Ontario Review Press, 1984), 133.

back to text - Sidney Hook, Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the Twentieth Century (New York: Harper and Row, 1987), 512.

back to text - Ibid., 519.

back to text - Phillips, Letters of Delmore Schwartz, 75

back to text - See discussion in Alan Wald, The New York Intellectuals: The Rise and Decline of the Anti-Stalinist Left from the 1930s to the 1980s (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), 146-47.

back to text - “The Liberal Fifth Column,” Partisan Review XIII, No. 3 (Summer 1946): 279-293.

- Atlas, 282.

back to text - Delmore Schwartz, “The Duchess’ Red Shoes,” Partisan Review 20 (January 1953): 55-73.

back to text - Barrett, The Truants, 105.

back to text - “We do not at all pretend to deny the significance of the personal in the mechanics of the historic process, nor the significance of the personal in the accidental. We only demand that a historic personality, with all its peculiarities, should not be taken as a bare list of psychological traits, but as a living reality grown out of definite social conditions and reacting upon them.” Trotsky, Leon, History of the Russian Revolution, Volume I (London: Sphere Books Limited, 1967), 104.

back to text - Delmore Schwartz, “Ballad of the Children of the Czar,” Selected Poems, 21.

back to text - Delmore Schwartz, “The Ghosts of James and Pierce in Harvard Yard,” Selected Poems, 51.

back to text - A fuller analysis of these stories will appear in the essay, “The Lost Partisan,” in a collection of new essays edited by Ben Mazer, probably 2022.

back to text - Saul Bellow, Humboldt’s Gift (1975), 11.

back to text

May-June 2012, ATC 212