Against the Current No. 211, March/April 2021

-

Transition, Trauma, and Troubled Times

— The Editors -

Health Care Inequalities, Racism and Death

— Malik Miah - Support Kshama Sawant

-

Detroit Police, Image and Reality

— Dianne Feeley -

What About the Shootings?

— Dianne Feeley -

Analyzing the 2020 Election: Who Paid? Who Benefits?

— Kim Moody -

The First Fourteen Days

— Kim Moody -

"No One Is Coming to Save Us"

— Kit Wainer interviews MORE activists Shoshana Brown, Ellen Schweitzer, Mike Stivers & Annie Tan -

Puerto Rico's Multi-layered Crisis

— Rafael Bernabe -

White Supremacy and Labor's Failure

— Cody R. Melcher interviews Michael Goldfield - On Socialist Feminism

-

Second-Wave Feminism: Accomplishments & Lessons

— Nancy Rosenstock -

A Socialist Woman's Experience

— Suzanne Weiss - Reviews

-

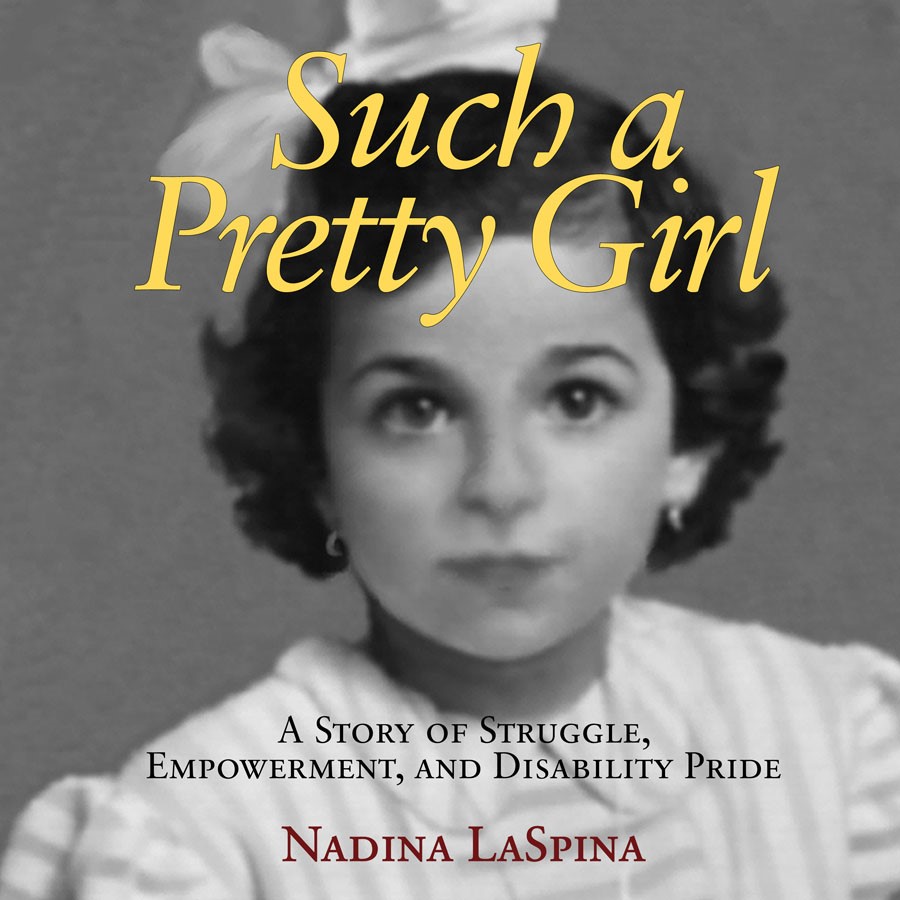

A First-Generation Disability Story

— Brenda Y. Rodriquez -

In the Imperial Crosshairs

— David Finkel -

The Deadly Metabolic Rift

— Tony Smith - In Memoriam

-

Gabe Gabrielsky: A Radical Affirmation

— Promise Li - Gabe Gabrielsky: A Few Facts

Brenda Y. Rodriquez

Such a Pretty Girl

A Story of Struggle,

Empowerment, and Disability Pride

By Nadina LaSpina

New Village Press, 2019, 338 pages, $19.97 paper.

SUCH A PRETTY Girl, Nadina LaSpina’s memoir describes the life of a girl brought to the United States from Italy by her religiously and culturally Catholic Italian parents in the hope of finding a cure for her polio. If she could have surgery that would enable her to walk, they felt she could live “a normal life.”

As a child growing up in her Sicilian hometown Riposito, she also understood that neighbor women viewed her mother as a “sorrowful woman,” burdened by having a child who could not walk. With her mother carrying her everywhere, she too accepted their negative view.

While her family was able to fulfill their dream of migrating and getting her to the Hospital for Special Surgery, LaSpina began a journey toward an independent life quite different from her parents’ expectations.

Much of the memoir recounts decisions she makes that her parents find difficult to understand. Although she develops confidence, lives independently and teaches Italian and French at the university level, she eventually realizes she is unable to fulfill her father’s dream of being able to walk. Even with the aid of crutches, she was continually falling and breaking her legs.

She came to the decision to have her legs amputated and be fitted with prosthetic legs. After all that her parents had done for her, she wondered how could she let them down. Her mother explained that it is particularly difficult for her father, “because of experiences he had in the war, seeing soldiers with their legs blown off….”

In both Sicily and the United States doctors had focused on healing her legs with unworkable treatments. She was determined put that dream behind her, along with its pain and suffering. With this decision she embraced her disability as her identity; she saw herself most at home within the disability community.

Yet it was also an identity of fierce independence. When a fellow teacher fell in love with her, she eventually rejected him because he wanted to take care of her in a way that seemed abusive. She was capable to taking care of herself — and instead she found a life partner within the disability community.

Sometimes it is difficult for a person to understand decisions another might make, particularly around how to measure “quality of life.” LaSpina mentions that her partner was asked, by a hospital social worker, if he would want to be resuscitated if his heart stopped during surgery. When he said he’d want to live no matter the limitations, the social worker seemed surprised. LaSpina notes that “ableism” is one of the norms capitalism imposes.

At a Disability Independence Day rally, in her speech LaSpina explained what demonstrators meant when they shouted “We Shall Overcome:”

“We just want to make sure everyone understands that, when we sing ‘We Shall Overcome,’ we are not saying: we shall overcome our disabilities. For too long, we were made to believe that we had to get over all the obstacles that were put in our way with our willpower. If we couldn’t be cured, we had to make our disabilities as inconsequential as possible in order to fit in. That was called ‘overcoming.’ No more of that! We do not overcome our disabilities, we just live with them. Some of us not only accept our disabilities but we embrace them, because we know, even if they cause us pain, our disabilities are a very important part of who we are. We are no longer willing to minimize, camouflage, suppress that important part of ourselves…” (253-4)

Founding Disability Studies

Nadina savors the identity of an individual with disabilities with pride. From the beginning of her successful teaching career, she noticed how students saw her as different because of her disability. By 1996 she decided to approach Sondra Farganis, head of the Social Sciences Department at the New School, at a faculty party with her idea:

“Disability studies examines and theorizes the social, political, cultural, and economic factors that define disability. It is comparable to women studies. I’d read her book Situating Feminism and made a reference to it. She sipped her wine and nodded. ‘Write me up a course proposal.’

“I couldn’t believe my ears. I was thrilled to be given the opportunity, but also to have found someone who seemed to ‘get it.’ More than once at the New School I’d been bitterly disillusioned when a colleague I admired showed little understanding of disability. The most enlightened seemed to think it all boiled down to the need for accessibility.” (280)

As she developed her classes she shared her life experiences through the courses she taught under the disability studies discipline. These courses made her feel exposed, unlike when she was the “Italian teacher.” Language and its grammar are very different from disability studies in its discussions of ableism and identity.

The author explains how she went from teaching in the Languages and Social Sciences departments to devoting herself to teaching courses on disability studies (both in-person and online) in the Social Science department. This was the moment when her life seemed revolved around disability activism as she assumed leadership roles along with her partner. She had not realized what a strong advocate she could be and was amazed to see how it had become her focus!

As a first-generation American with physical limitations, I found in reading Such a Pretty Girl that it was not only a very familiar story, but a memoir projecting possibilities. Similar to Nadina’s parents’ hopes, mine have always been hopeful that I could achieve full hearing and perfect vision. I enjoyed learning about her determination and resistance to the ability quo and see her as a role model.

March-April 2021, ATC 211