Against the Current No. 208, September/October 2020

-

The Pandemic and the Vote

— The Editors -

"Good Trouble, Necessary Trouble"

— Malik Miah -

Black Lives Matter & the Now Moment

— Anthony Bogues -

Why Send Troops to Portland?

— Scott McLemee -

A Victory, an Unfinished Agenda

— Donna Cartwright -

Your Postal Service in Crisis -- Why?

— David Yao -

Solidarity's Election Poll

— David Finkel for the Solidarity National Committee -

Why Green? Why Now?

— Angela Walker -

Opening Up the Schools?

— Robert Bartlett -

Toward a Real Culture of Care

— Kathleen Brown -

Toward Class Struggle Electoral Politics

— Barry Eidlin interviews Micah Uetricht & Meagan Day -

C.T. Vivian, Organizer and Teacher

— Malik Miah -

Behind Lebanon's Catastrophe

— Suzi Weissman interviews Gilbert Achcar - Support for Mahmoud Nawajaa

-

Dead Trotskyists Society: Provocative Presence of a Difficult Past

— Alan Wald -

Nonviolence and Black Self-Defense

— Dick J. Reavis - Reviews

-

Experiments in Free Transit

— Joshua DeVries -

Studying for a New World

— Joe Stapleton -

The Fight for Indigenous Liberation

— Brian Ward -

At Home in the World

— Dan Georgakas -

The Larry Kramer Paradox

— Peter Drucker - Larry Kramer, a Brief Biography

Scott McLemee

SOMEDAY HISTORIANS WILL look back on the cascade of events in 2020 and probably conclude that developments in the United States took a sinister turn on or about July 15.

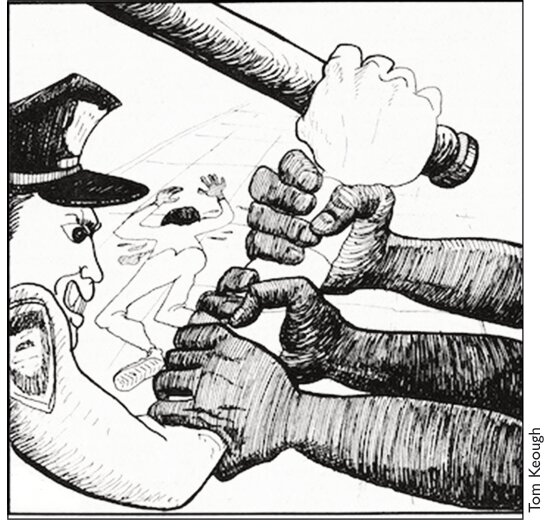

That day, troubling reports started coming out of Portland, Oregon, where, as in countless other parts of the country, mass protests against racism and police brutality were underway. The word among activists on social media was that protesters were being grabbed up by people in military fatigues bearing patches that identified them only as “police” who were cruising the streets in unmarked cars and vans.

Cellphone video recordings soon proved that this was no wild rumor. One individual, shown being carried off to a van, later reported that he was held at a federal courthouse, where he was given the Miranda warning (“You have the right to remain silent…”) but was never told the grounds for arrest or what agency was holding him.

Following media inquiries, U.S. Customs and Border Protection released a statement that it acted on “information indicating the person in the video was suspected of assaults against federal agents or destruction of federal property.” CBP also claimed that its agents had identified themselves and were wearing CBP insignia.

“I have a pretty strong philosophical conviction that I will not engage in any violent activity,” the detained protester told The Washington Post. After refusing to waive his rights, he was released from custody but given no record of the arrest.

The number of people detained in this manner is probably known only to the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees CBP. More than a hundred DHS agents (including some from Immigration and Customs Enforcement) were in Portland in July as part of Operation Diligent Valor — despite clear indications by the city’s mayor and Oregon’s governor that they were neither welcome nor needed.

Expanding Deployments

By early August, DHS was circulating “open access security reports” on two reporters covering Portland for the national news media to law enforcement agencies. They consisted largely of material culled from the journalists’ Twitter accounts.

In addition, the department circulated information on arrested protesters presented in “baseball card” format. The intention to provoke or prolong harassment was clear in each case.

In the meantime, Department of Justice sent 200 federal agents to Kansas City on the pretext of fighting violent crime. While slightly less grandiose-sounding than DHS’s Diligent Valor, the DOJ’s Operation Legend (also called Operation LeGend) was no less an effort to derail social protest.

The mean streets of Kansas City seem far less credible as a concern of the Trump administration than protesters’ demands that local law-enforcement funds be redirected to meeting residents’ health, education, and housing needs.

Other cities targeted for LeGend deployments are Albuquerque, Baltimore, Cleveland, Detroit, Memphis, Milwaukee, Philadelphia, and St. Louis, Missouri.

Who Is Being Targeted — and Why?

Far less worrying to federal authorities throughout this period have been the right-wing protesters who, besides denouncing efforts to limit the spread of the coronavirus, are prone to issue death threats and march around with weapons to back them up. (Some also bear swastikas and Confederate flags, suggesting that the inalienable right not to wear a mask is, at most, a secondary issue.)

During rallies against stay-at-home orders in Michigan this spring, gun-bearing protesters threatened the governor with lynching. In his testimony before Congress in late July, Attorney General Bill Barr pretended not to have heard about it. Nor did he bother to make the faintest of half-hearted gestures of concern.

The viciousness of reactionaries tends to grow in direct proportion to the urgency of the social demands being made, and the course of 2020 has been no exception.

With deaths from the pandemic in the United States in the six figures while the unemployment rate remains double-digit, teachers around the country prepare to go on strike if necessary rather than let their schools reopen as centers for the spread of disease. People whose right to a living wage has been denied find themselves classified as essential workers — without whom nothing else functions, even badly.

The potential for rent strikes and militant resistance to eviction grows, as does recognition that universal healthcare and a basic income are reasonable demands.

At the same time, everyone paying attention realizes that for the white-nationalist Republican party to remain a factor in American politics, it has to suppress the vote among the communities hardest hit by the pandemic. And those throwing protesters in vans aren’t just curiously neglecting to notice the paramilitary right but hanging out with them on social media.

As we go to press in August 2020, one year has passed since the investigative site Pro Publica revealed the existence of a virulently racist and xenophobic Facebook group with 9,500 followers drawn from past and present agents of the Customs and Border Protection. Following a remarkably under-publicized investigation, CBT fired four agents, suspended 38 without pay, and warned a few more to knock it off.

The impact on the other 9,400 or so has not been reported. But one thing seems clear: Whatever else it may have been, Portland in July was just practice.

September-October 2020, ATC 208