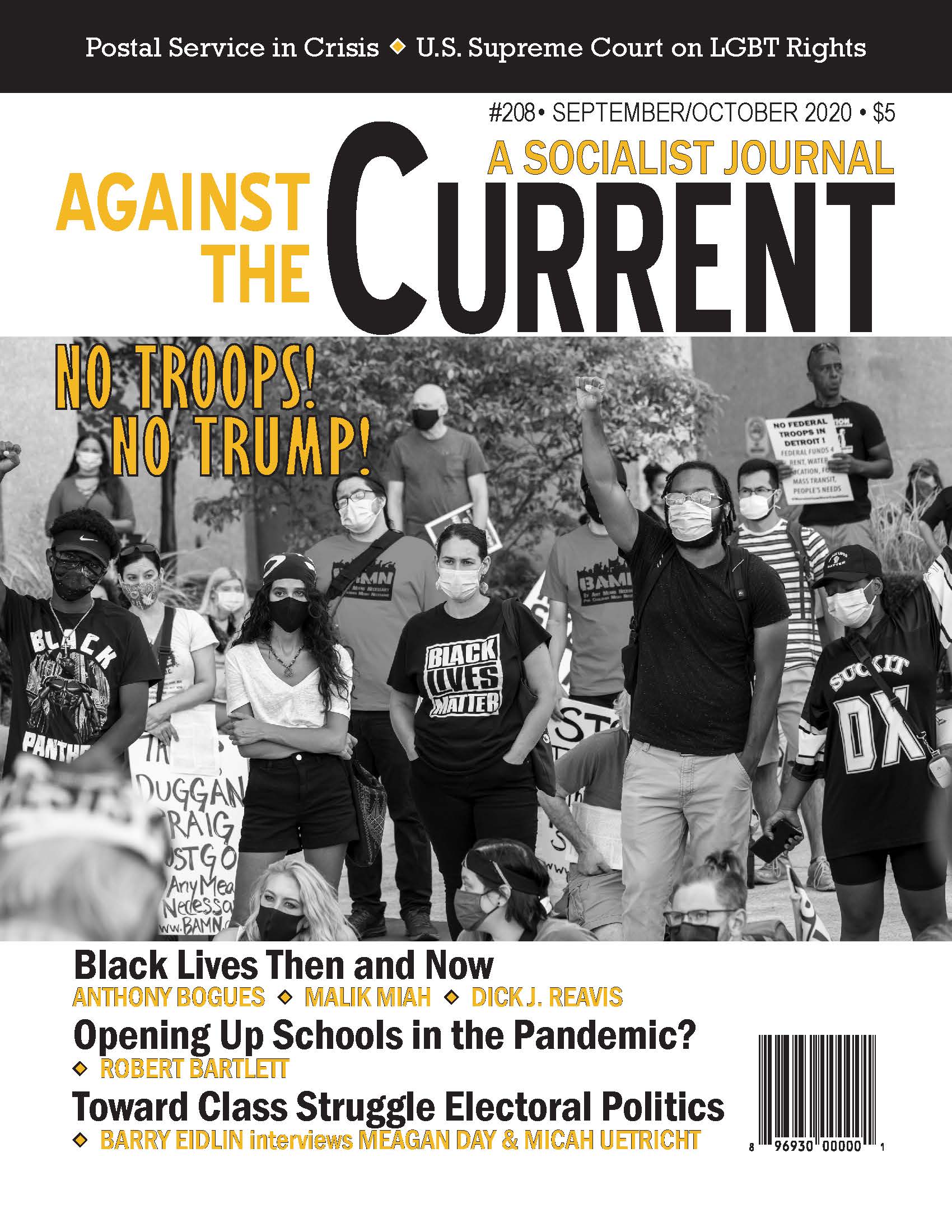

Against the Current No. 208, September/October 2020

-

The Pandemic and the Vote

— The Editors -

"Good Trouble, Necessary Trouble"

— Malik Miah -

Black Lives Matter & the Now Moment

— Anthony Bogues -

Why Send Troops to Portland?

— Scott McLemee -

A Victory, an Unfinished Agenda

— Donna Cartwright -

Your Postal Service in Crisis -- Why?

— David Yao -

Solidarity's Election Poll

— David Finkel for the Solidarity National Committee -

Why Green? Why Now?

— Angela Walker -

Opening Up the Schools?

— Robert Bartlett -

Toward a Real Culture of Care

— Kathleen Brown -

Toward Class Struggle Electoral Politics

— Barry Eidlin interviews Micah Uetricht & Meagan Day -

C.T. Vivian, Organizer and Teacher

— Malik Miah -

Behind Lebanon's Catastrophe

— Suzi Weissman interviews Gilbert Achcar - Support for Mahmoud Nawajaa

-

Dead Trotskyists Society: Provocative Presence of a Difficult Past

— Alan Wald -

Nonviolence and Black Self-Defense

— Dick J. Reavis - Reviews

-

Experiments in Free Transit

— Joshua DeVries -

Studying for a New World

— Joe Stapleton -

The Fight for Indigenous Liberation

— Brian Ward -

At Home in the World

— Dan Georgakas -

The Larry Kramer Paradox

— Peter Drucker - Larry Kramer, a Brief Biography

Alan Wald

US Trotskyism, 1928-1965

Part I: Emergence. Left Opposition in the United States

Edited by Paul Le Blanc, Bryan Palmer & Thomas Bias

Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books, 2019, 704 pages, $36 paper.

Part II: Endurance. The Coming American Revolution

Edited by Paul Le Blanc, Bryan Palmer & Thomas Bias

Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books, 2019, 835 pages, $50 paper.

Part III: Resurgence. Uneven and Combined Development

Edited by Paul Le Blanc & Bryan Palmer

Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books, 2019, 719 pages, $36 paper.

THIS ESSAY IS dedicated to the memory of Anne Chester, Froben Lozada, Asher Harer, Kwame Samburu, Nat Weinstein and Sylvia Weinstein — working-class heroines and heroes.

EVEN THOUGH ALLEN Ginsberg’s “America” was not among the ardent verses recited in the 1989 teen drama Dead Poets Society, his 1956 anti-capitalist protest poem hurled a celebrated challenge of defiance against the stifling conformity of his native land: “When will you be worthy of your million Trotskyites?”

Lamentably, so far as our present-day political culture goes, an inspection with a microscope might indicate an oversupply of competing Trotskyist groupuscules, and almost no demand. Viewed through regular glasses, the larger picture suggests that it’s mostly all quiet on the Trotskyist front, and has been so for quite a while.

I. Where Have All the Trotskyists Gone

In the 1930s, U.S. adherents of exiled Bolshevik Leon Trotsky in the international communist movement led a spectacular teamster strike in Minneapolis and were a dazzling pole of attraction in New York intellectual life. In the 1960s Trotskyists provided expert leadership for the Fair Play for Cuba Committee and the anti-Vietnam War movement, and in the 1970s established vital networks of rank-and-file unionists.

Such a track record augurs an appealing resource for young activists to investigate, with the aim of reinventing a vibrant socialist movement by studying earlier applications of Marxism to labor, race, international politics, organization-building, coalitions, elections, and much more.

Yet the memory of undeniable accomplishments is in jeopardy of displacement. The last time I recall the term “Trotskyism” inviting truly national attention was in 2011, on the occasion of the death at age 62 of the well-known “contrarian” journalist Christopher Hitchens. The New York Times described Hitchens as “a British Trotskyite who had lost faith in the Socialist movement”(1) and Channel 4 News quoted Scottish politician George Galloway ridiculing him as “a bloated, drink-sodden former Trotskyist lunatic.”(2)

Whether the meshugaas of Hitchens’ political apostasy signified the “twilight” of Trotskyism, or simply transported us momentarily into its “Twilight Zone,” is a puzzler that might be debated.

But fear not. This review essay of a three-volume documentary history of U.S. Trotskyism is addressed to committed militants — not cynics or laptop Bolsheviks. The Introduction to Volume III explains why this recovery project matters:

“The people who were drawn to the Trotskyist banner sought to forge a genuinely revolutionary pathway from the violence and oppression of capitalism to a better future of socialist democracy, the control of the world’s economic resources by laboring majorities for the good of humanity — a cause which they believed had been betrayed by the bureaucratic leaderships and badly compromised programs of the mass reformist-Socialist parties and by the global Communist movement led by Joseph Stalin.”(3)

That is, while always marginal as a social movement in the United States, Trotskyism’s relatively distinctive ideas and experiences may assist in the present-day recomposition of a new revolutionary socialist agenda to meet the extraordinary times in which we live.

Conversely, some kind of “fight for the soul of Trotskyism” is the opposite of what we need. Accordingly, in what follows, there will be no deluging you with wild and wonky tales of bizarro shenanigans or, alternatively, extolling the delights of engaging in doctrinal hairsplitting (“The Joy of Sects”).

We are in a moment of danger for our society and the future of the socialist Left. As I write, deaths from COVID-19 are steadily mounting; a global anti-racist movement contesting the funding of murderous cops is underway; mass actions to eradicate shrines to traitors and bigots are sweeping several countries; agonizing impoverishment and off-the-charts unemployment show every sign of persisting and deepening; and an unhinged president grows more barking every day.

More than merely a year, 2020 could well turn out to be more of a historical conjuncture — like 1929, 1939, 1956 or 1968. The road ahead is coming into view as even more forked than usual.

Will there be an advance toward greater working-class solidarity and increased understanding of the roots of racism in political economy, or an upsurge in the hammer-blows of immiseration and repression? Is the course of history about to be transformed, or are we facing a speed-up of alterations already in progress?

The Left, justifiably, is embroiled in contentious debates about the next stage while we all wonder what is to be done. In our search for guidance, this is no time for indulgence in the perusal of archaic texts as an act of necromancy to predict the future. On the other hand, surely there is merit in revisiting an earlier moment of bold creativity when true socialist internationalism was imaginable, and activists gave their all to bring it about.

II. St. Paul of Trotskyism

A portal back to precisely such a time in radical history landed with a surprisingly heavy thud on my front porch this spring — a box containing 2258 pages of primary sources and commentary under the rubric of “US Trotskyism, 1928-1965.”(4)

Multiple door-stop tomes is what I might have foreseen because the never-ending production of internal discussion bulletins and journal articles was a Trotskyist tell; but who would be willing to furnish the sheer Stakhanovite intensity of labor to pull all this together? More to the point, what would motivate young activists to read it?

The answer to the first question is Paul Le Blanc, the éminence grise behind this remarkable trilogy of lost and marginalized voices, and with all due respect to James Brown, the hardest working man in revolutionary historical studies. He is author of close to a dozen monographs, but also a tireless compiler of essay collections of works by V. I. Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Antonio Gramsci, Rosa Luxemburg, C. L. R. James and more.

Customarily a vastly busy one-man band, Le Blanc in this particular documentary series engages the assistance of two associates: Bryan Palmer, the stellar historian whose two-volume Marxism and Historical Practice became available in paperback in 2017 from Haymarket Books, and socialist Thomas Bias (1950-2019), a much-admired political activist in the International Typographical Union.

The resulting product is Le Blanc’s most ambitious effort to date, an orchestra of documents rescued from the pages of publications of the main Trotskyist group, the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and its predecessors, spanning the years from 1928 to 1965.

As an activist scholar, Le Blanc himself is of an exceedingly rare breed. From a pro-Communist family, and with New Left bona fides as a one-time member of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and a Conscious Objector in 1966 during the Vietnam War, Le Blanc labored in the orthodox Trotskyist vineyards of the SWP and Fourth Internationalist Tendency (an expelled group seeking readmission) for decades before veering off to join the more heterodox Solidarity and International Socialist Organization (ISO), and now the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA).

Such an itinerary may look like a version of Marxist speed-dating, or serial monogamy, but Le Blanc entered each of these commitments with honorable intentions. More noteworthy, he emerged from these involvements with a mature and admirable temperament: as an optimistic peace-maker, far from the heated world of his political ancestors and many of his one-time comrades.

He may well be christened “The St. Paul of Trotskyism,” in this instance appropriate for a comrade supremely devoted to popularizing and giving intellectual weight to the classical tradition. In innumerable debates filling a wide range of publications on the Far Left, he is unfailingly cordial even as he is persistent in defending his arguments, qualities on display in his management of US Trotskyism.

III. A Magisterial Assembly of Archival Materials

In this massive collection, Le Blanc is able to command numerous moving parts so that, while I can’t promise that everyone will find the read a heart-pounding thriller all the way to the end, there are treasures in every volume.

I am especially struck by the multitude of riveting Marxist activist-writers who applied protean talents to understanding capitalism and imperialism in the worst decades of the last century. This encompasses not only the redoubtable leaders whose political writings have been in print for many years, such as James P. Cannon, Max Shachtman, Farrell Dobbs, C. L. R. James, Art Preis, Fred Halstead, George Breitman, George Novack and Evelyn Reed. There are also those who would, for various reasons, eventually quit or be excluded from the movement, but possessed talents revealed soon after in striking ways.

If one wants to see how a Marxist analyzed the Nazi invasion of France at first hand, there is “How Paris Fell” (1941) by Sherry Mangan (writing as “Terence Phelan”), the modernist poet and translator in 1955 of the Juilliard Opera Theater’s landmark production of Mozart’s Idomeneo, King of Crete.

For rare particulars about the conditions faced by revolutionaries under the fascist occupation, see “Europe Under the Iron Heel” (1942) by Jean van Heijenoort (writing as Marc Loris), a world-famous historian of mathematical logic and expert on Kurt Gödel. To grasp what ensued in the postwar labor movement, there is “The Great Strike Wave and Its Significance” (1946) by Bert Cochran (writing as E. R. Frank), the author of the masterful Labor and Communism: The Conflict that Shaped American Unions (1977).

To see the elements of a theory of Stalinism presented as an alternative to Trotsky’s, check out “State Capitalism and World Revolution” (1950), co-authored by C.L.R. James along Raya Dunayevskaya, founder of Marxist-Humanism and author of books on philosophy and women’s liberation, and Grace Lee Boggs, the legendary Detroit activist and autobiographer of Living for Change (1988).

To understand how a Marxist interpreted the controversial period from the election of Andrew Jackson to the Civil War, see “Three Conceptions of Jacksonianism” (1947) by Harry Braverman (writing as Harry Frankel), the author of the Marxist classic Labor and Monopoly Capitalism (1974). An incisive critique of “The Myth of Racial Superiority” (1944) is provided by former psychology professor Dr. Grace Carlson, the subject of Donna T. Haverty-Stacke’s forthcoming The Fierce Life of Grace Holmes Carlson: Catholic, Socialist, Feminist (2020).

The bulk of this magisterial assembly of archival materials is drawn from articles appearing in Trotskyist newspapers and journals, internal documents, book reviews, and letters and reports, but substantial space is also devoted to introductions that open each book and precede each section. These amount to 76 pages in Volume I, 57 pages in Volume II, and 51 pages in Volume III, a total of 184 pages. Thus the trilogy contains a collectively-written historical narrative that is a small book on its own.

Le Blanc himself prepared the vast majority of these prefaces and overviews, a total of 15. Palmer contributed four and co-authored one; Bias wrote two and co-authored one; and Andrew Pollack, another political activist, contributed two to the first volume only.

The attention-grabbing titles of each volume tell a kind of story of “Emergence,” “Endurance,” and “Resurgence.” Admittedly, this amounts to a narrative arc often found in fiction, especially in tales that climax in a happy ending — which turns out not at all to be the case, especially when the trajectory of the Trotskyist movement is viewed from the 21st century. The internal partitions of the material, from my point of view, are well-crafted, although the weight of the selections included in each chapter fluctuates considerably.

Volume I covers the formation of the Trotskyist movement in 1928, with the founding of the Communist League of America, and runs to the beginning of World War II, with the 1941 Smith Act Trial that sent leaders of the SWP leadership and Teamster Union activists to prison for allegedly advocating the violent overthrow of the U.S. government. This unit has eleven chapters, ranging from two to nine items in each.

The most extensive deals with the 1939-40 dispute between supporters of James P. Cannon and Max Shachtman, the equivalent of a Thunderdome. It was a political cage match event that involved disputes over the organizational character of the SWP as well as the actions of the Soviet Union (invading Poland and Finland) at the start of World War II.

The volume also includes exceptionally well-informed chapters, grounded in dense research by Palmer, about the CLA, “Labor Struggles,” and “The Smith Act Trial.” In the introduction to this final segment, Palmer’s gifts are stunning as he creates a lucid and compelling narrative connecting the copious dots among various aspects of the SWP’s Teamster activity, Trotsky’s criticisms of his supporters’ labor policy from Mexico, the threat of fascist groups in Minneapolis, the role of Trotskyists in the nationwide WPA strike, the collaboration of the FBI with the head of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, the handling of the trial defense, the dispute with ultraleft critics in the Fourth International, and much more.

The book closes with a small selection of historical and theoretical essays from the era by SWP leaders such as Felix Morrow, Albert Goldman, George Novack (writing as William F. Warde), and C. L. R. James (writing as J. R. Johnson).

The second volume, comprising the postwar and early Cold War years, has five chapters varying from four to 17 items. They take up the “Dawn of the American Century,” “Challenging Racism,” “Dissensions” (disputes with minority groupings led by Morrow and Goldman, and James), “Coping with the Cold War, Global and Domestic,” and “Confrontations Internal and International.”

In this last subdivision, among the longest, Palmer caught me off guard by lapsing into a boilerplate tract against the favorite Dark Side Trotskyist of so many dogmatists — the Egyptian-born Greek Marxist Michel Pablo (a pseudonym for Michalis N. Raptis). What to make of a one-sided polemic capped by a denunciation of the reunification of the Fourth International — 20 years down-the-road! — as “rooted in a common Pabloite orientation to the Cuban Revolution….”?(5)

Without entering into an Olympian debate over the question, let me briefly state that “Pabloism” has become an umbrella term for working up a bloodlust against non-sectarian Trotskyism. It was certainly appropriate for Palmer to indicate his own opinions, but those seeking a more informative view of Pablo’s mixed contribution to revolutionary Marxism would do well to consult the summary found on the Marxist Internet Archive.(6)

Mulling over these uncharacteristic pages in US Trotskyism, one wonders whether the invocation of the name “Pablo” is everlastingly destined to have the same effect on the orthodox Trotskyist mind as the full moon used to have on werewolves.

The third volume, covering new radical developments in the mid-1950s and early 1960s, contains six chapters ranging from five to 12 items each, this time closing with an even more extensive selection of history and theory that includes writing by several women — Grace Carlson, Jean Simon (a pseudonym for Jean Tussey), Myra Tanner, and Joyce Cowley.

Broadly conceived as showcasing what Le Blanc nicely calls “A Party of Uneven and Combined Development,” this concept — better known as a political-economic theory — is here applied to illuminate “a left-wing organization, particularly one spread over different geographic areas, with diverse social composition, embracing different generations, and interacting with co-thinkers in various other countries as well as with the complex and evolving society within which it is embedded.”

Le Blanc further adds that such a dialectical contradiction can also be found “within an individual who is a leading member of such an organization.”(7) This lead-in advances to a reflective and creative interrogation of the sectarian as well as non-sectarian aspects of the SWP, followed by a convincing description of its achievements in the 1960s.

Quoting long-time SWP leader George Breitman, much of this success is attributed to “listening to and learning from non-Marxist figures — such as Malcolm X, Rev. Cleage, William Worthy, Jesse Gray, Daniel Watts, James Baldwin, the exiled Robert F. Williams and Julian Mayfield….”(8)

One might accordingly characterize this forward thinking that was extant in the late 1960s as a sort of “vegetarian” phase of SWP development, then regrettably followed by a disastrous “carnivorous” one. For the latter, Le Blanc concludes this Introduction with a brief but pointed summary of the party’s transformation in the 1970s.

For various reasons the once working-class organization was turned over in 1971 by the Old Guard to a new student leadership (mainly a friendship circle from the elite Carleton College) that successfully embraced organizational “authoritarianism” and then, suddenly, a homemade version of “Castroism.” It was a frog-in-boiling-water situation with the hand of one Jack Barnes on the burner, and the meal finally cooked up was a bland and “politically irrelevant sect.”(9)

IV. “Normie” Trotskyism?

There is no way to fairly describe the full scope of these volumes, hence some highly selective and hopefully constructive observations will have to suffice.(10) In the interests of putting the bottom line up front, I’ll just come out and state my main point here: Any hope for the redemption of aspects of this tradition will come from candidly posing the problems that are the concerns of the activist Left at the present time. If these are not clearly named, they can’t be addressed.

In contrast, a surefire path to irrelevance is to lecture the activists with certainty about “correct positions” once held by the movement with little consciousness that many of these are replete with policies and practices that have so often led to disaster. US Trotskyism embodies both approaches, and is at its best when it tilts toward the former.

I long ago learned how to speak Trotskyism and have personally met and interviewed many of the contributors to this trilogy, but the novice radical who encounters US Trotskyism for the first time will be in a different situation.(11)

This means that guideposts and framings play a decisive part in how the raw material of these volumes is processed. Here I find that the Prefaces and Introductions by all the editors are unquestionably beneficial, albeit chiefly in delivering clear and compelling explanations of the origins of the Left Opposition led by Trotsky and the history of the various stages of the SWP.

On the other hand, there are no explanatory footnotes to the primary materials, nor are there chronologies, timelines, glossaries of key terms and biographical identifications, or a bibliographical essay mapping kinds and categories of available scholarly and archival resources.(12)

Readers without some background may have more than a little difficulty in remembering the differences among the American Workers Party, the Workers Party of the United States, and the Workers Party; or the Communist League of Struggle, the Marxist Workers League, the Leninist League, the Workers League, and the Revolutionary Marxist League. Neophytes might find themselves checking out on the particulars in favor of skipping ahead to episodes of melodramatic blood-letting and political purging à la Game of Thrones.

When one starts to count up the expulsions from the SWP (almost always described in these volumes euphemistically as splits, divergences, ruptures, and exits), one runs out of fingers and toes very soon. Some of these bitter altercations turn into venomous Forever Wars, especially those in which Cannon is opposed to Max Shachtman, and a dozen years later to Bert Cochran and George Clarke.(13)

In an article by Shachtman, ultra-leftists like Hugo Oehler and B. J. Field are discussed with relatively more leniency, even humorously. In contrast, the aforementioned — all once intimates of Cannon in the SWP leadership — are characterized by the SWP majority as incorrigible revisionists politically and men of bad faith personally.

Decades later, oppositionists would continue to be decried as clones of these renegade Darth Vaders (who was himself formerly a Jedi Knight); and in 2020, like Trump’s obsession with Obama, their names still live in the heads of many self-proclaimed “Cannonites” who seem addicted to re-enacting scenarios. I’ve even heard a few muttering, “Will no one rid me of these meddlesome Shachtmanites?” But I’ve also observed neo-Shachtman supporters fantasizing crypto-Stalinism every time the name Fourth International crops up.

No wonder that present-day activists might conclude that the mentality of sectarian factionalism seems to operate within the larger movement of Trotskyism as if a virus; a snippet of chemical memory that repeats itself numerous times. Do these volumes acquiesce in an acceptance of this, or do any of the contents seek out some means of immunization against the worst forms of the disease or at least achieve a flattening of its curve by preventive measures?

By and large, US Trotskyism follows the playbook of the authorized writings of the SWP, especially the narrative found in Cannon’s The Struggle for a Proletarian Party (1943), The History of American Trotskyism (1944), Speeches to the Party (1973), The Struggle for Socialism in the “American Century” (1975), and The Socialist Workers Party in World War II (1977), as well as compilations such as Trotskyism Versus Revisionism: A Documentary History (1973), edited by a British anti-Pabloite named Cliff Slaughter.

I don’t mean to suggest that the account provided is entirely uncritical. Le Blanc is acute in censuring the SWP’s 1930s blind-spot on race (worthy of a hashtag #TrotskyistsSoWhite), while Palmer maintains that Cannon was insufficiently anti-Pablo (“his critique was not a decisive repudiation of the politics of Pabloism”) and even guilty of “national chauvinism.”(14)

From the outset, however, the perspective is that all the losing oppositions in the SWP were ones that “fundamentally disagreed and broke away.”(15) That makes the contents of US Trotskyism mostly comfort food to those educated in the SWP traditions. The menu may be less tasty to those who seriously doubt that all the ruptures in the SWP involved issues of fundamental (therefore, split-worthy) principle, and who even might suspect that undemocratic and bureaucratic means may have been at times used by the SWP majority.

Are the editors, following the SWP positions to such a large extent, actually advancing and reproducing a political version of a “Normie Trotskyism” for the present generation? My view is that the trilogy is normie to the degree that it commends this orthodox and unadventurous perspective on the past as an interpretative norm.

While US Trotskyism, especially in passing references by Le Blanc, occasionally opens the door to new avenues of discussion and reconsideration, the gap is never very wide and I find that too little passes through. Le Blanc several times emphasizes that the authors of the introductions have “different ‘takes’…on both minor and major questions,” but it would have been helpful to say explicitly what a few of these are, and even to provide meaningful comparisons.(16)

Likewise, Le Blanc offers encouraging general statements about the need to develop a “superior paradigm” to “replace variants of the old perspectives…in these pages,” ones that “may end up synthesizing new conceptualizations with those drawn from the richness of the Trotskyist tradition.” Still, his main example is that of the occasional infusion of “‘heterodoxy’ into the reigning ‘orthodoxy,’” which needs a much more detailed elaboration than is provided.(17)

For the most part, despite the strategic presence in the book of routine platitudes about no faction being perfect, and all sides having some valid point, the volumes encourage an “us versus them” perspective, and the “us” is repeatedly the SWP majority faction.

One suggestion for future consideration is for the serious student of Marxist theory and practice to revisit the debate about the nature of the Soviet Union, to ask whether the bitter rupture among dedicated anti-capitalists was objectively necessary to pursue for so many decades, especially as there was frequently a convergence in opposing Soviet repression (in East Germany 1953, Hungary 1956, Czechoslovakia 1968) as well as episodic near-collaborations.

Can one now acknowledge that extended adherence to seeing the world through the prism of one of these singular theories (there were at least five or six) was based on understandably poor information and exaggerations on all sides due to factional rivalries? Maybe there are still reasons to be skeptical of a unification before 1989, but the USSR collapsed 50 years after the original schisms began in a manner that (at least in my view) confirmed no one’s pet model.

Moreover, was it so absolutely critical for the SWP to decide on one single analysis of such a highly complicated question as “the” official position when an organization of around 1000 people had absolutely no influence on governmental policy or anywhere else? To his credit, Le Blanc mentions Marcel Van der Linden’s highly relevant argument for a synthesis of elements of the various Marxist theories of Stalinism, but then he neither develops nor integrates that perspective into his estimation of the SWP legacy.(18)

Another possible dispute to revisit concerns Cannon’s expectation of the SWP in the post-World War II era gearing up to lead a transition to the dictatorship of the proletariat at warp speed. This was way off, yet those who had accurately questioned that analysis were treated rather harshly. What about providing an example of how, knowing what we now know, one might have used that clash of predictions in a productive debate that came closer to understanding postwar reality?

I raise such suggestions for consideration not because I favor counter-factual history, but because the Left of today needs to locate authentic grounds for unity. Some Marxist groupuscles act as if “regroupment” means everyone agreeing with their program. But only candid explorations of where a once-inspiring political current went wrong (as well as where it was accurate) will creatively address newly-arising situations. These will be ones in which we ourselves must debate about what is common ground and what is overreaching in the conditions of the 21st century, instead of accepting the dividing lines that have come before as a teleological inevitability.

As the French Marxist Daniel Bensaïd observed, “The Past is full of presents that never came to fruition.”(19) That’s surely why contemporary radicals continue to examine the rise of German fascism and the Spanish Civil War to assess whether different policies might have produced more favorable outcomes.(20)

V. What Would Cannon Do?

The Marxist movement of 2020 confronts many situations for which much of the material in this trilogy provides not a template, but intriguing examples of earlier efforts to offer perspectives on analogous challenges: combining the struggle against race and class oppression; the problem of revolutions that over-reach and subsequently decline; international solidarity and anti-imperialism; self-defense against repression; the nature of fascism and how to build unity to oppose it; Marxist electoral strategy; and the necessity of revolutionary organization.

This last topic is hardly a sideshow, inasmuch as Cannon saw “party building” as a central concern. Nevertheless, radicalizing young people continue to either fear commitment to a serious organization due to a long history of cult leaderships and purges, or else they naively jump right into groups (not necessarily Trotskyist) that repeat the old mistakes as tragedy and farce.

Even experienced veterans find it painful to dispassionately revisit times past in which they had an emotional investment. Instead of rethinking their own role, they often resort to the by-now predictable rationalization that the organization betrayed its program or became a cult at the moment they were ejected. Furthermore, as one might expect, groups that currently imagine themselves as derived from the Cannon-era SWP act as if they have alleviated these critical matters, despite abundant evidence to the contrary.

In the volumes of US Trotskyism, there is little aimed at taking action in a fresh and informed manner to mitigate either of two interrelated perils. One is the paradoxical effect of the long-term charismatic and decisive leader, who accrues great prestige and becomes territorial about organizational control over time.

The other is the conundrum of when splits/expulsions are truly required, or result from political myopia and resistance to power-sharing. Neither is a simple matter, unless one chooses to merely side with the victors, which is the prevalent posture in these volumes.

Nonetheless Cannon, who radiated proletarian authenticity throughout his life, is an intriguing personality and political thinker, not the least because of his capacity to gather so many diverse and colorful individuals around him. The dilemma is that many complicated things happen as a leadership gains authority and becomes institutionalized; delusions of grandeur about one’s own political genius can be promoted by sycophancy.

By the same token, in a faction fight, several ostensibly conflicting claims may be true at once in gauging an unpredictable, complex, and fast-changing world situation. A full-blown pile-on, or treating minorities as untouchables, is guaranteed to cause a loss of faith in the likelihood of future fair treatment.

There is no doubt that, when it came to internal crises, Cannon was effective because he didn’t mess around; he went straight for the jugular as if loosing the fateful lightening of his terrible swift sword. Palmer reminds us on several occasions that Trotsky had chastised Cannon as early as 1933 for an “inclination to resolve political issues through organizational methods.”(21)

When one is reading through these volumes, however, one finds that Cannon’s opponents could often throw back charges of misbehavior as good as they got.(22) Focusing on one figure as the factional bogeyman in SWP history is as unwarranted as is continually asking, “What would Cannon do?”

Seventy or 90 years after these internal battles, I don’t see the point of indulging in a high dudgeon of retrospective partisanship when it comes to believing one faction’s truth about which side misbehaved in either a bureaucratic or “disloyal” way — or in excusing undemocratic behavior because the political line was allegedly superior. No one expects a political debate to showcase the graciousness of a maître d tending to a displeased customer, and it’s surely nothing more than a pleasant pipedream to fantasize, “What if there was a scheduled faction fight and nobody came?”

Instead of choosing sides retrospectively, it might be more constructive to the development of socialist culture to have a candid discussion that includes the psychological costs of bullying and belittling behavior, often accompanied by rancor and sneering, with the result of cadres being crossed out and embittered in these spirit-breaking purges.

VI. The Long View of Trotskyism

Looking back on the SWP experience chronicled in these volumes, one needs to think more circumspectly about the meaning of the legacy in a new millennium. Particularly pressing issues include the drastically changed state of capitalism and imperialism, and their war against the working class of the world, a crisis that still screams out for modernized socialist solutions.

To be sure, for the years just after these volumes conclude, it is hard not to be impressed with the achievement of Cannon in delivering the goods organizationally to a new generation in the 1960s. Despite all the episodic miscalculations and the diminution of its ranks, the SWP’s anti-capitalism and commitment to socialism remained steadfast.

With Cannon, Breitman and a few other “Dope Trotskyists” refurbishing their thinking in relation to shifting realities, it became possible for many of us — inspired by the New Left’s élan and dismayed by its structural collapse — to benefit from a still-functioning party that played a mostly positive role in the social movements of the new radicalization.

Then again, these gains turned out to be bewilderingly fragile. The elite student elements who would take over the SWP, and transform it through escalating sectarianism, effortlessly ascended to power only one year into the 1970s. As non-workers fully in command of an ostensible “workers” party, they completed their political and organizational makeover less than a decade after that.

In other words, if one starts with the 1939-40 schism, the SWP that Cannon built survived not much more than four decades, while Shachtman’s organization (Workers Party/Independent Socialist League) folded after barely two decades, and Cochran’s (American Socialist Union) after one decade.

From a long view of five decades later, the difference doesn’t seem so momentous as some of us once thought. And the membership disparities of groups of between 200 or 400, or an occasional bump to 1,000 or so, seem negligible in comparison to what is required for a major impact. This is a trilogy with a cut-off date of 1965, but it is haunted by a ghost from the future.

Nevertheless, there is no doubt that the seeds of Trotskyist ideas have spread widely. No one is suggesting that “We are all Trotskyists now,” which would not be desirable; but elements from Trotskyist thought have sometimes percolated through the broader radical culture in ways that renew Marxism. While many SWP luminaries have not gotten the attention they merit, C. L. R. James, Hal Draper, Raya Dunayevskaya, Grace Lee Boggs, Harry Braverman, and Sidney Lens are just a few admired names among the U.S. far left with a Trotskyist past, while Michael Harrington and Irving Howe are icons among liberal social democrats.

From Western Europe, there is considerable admiration for the work of Isaac Deutscher, Tariq Ali, Ernest Mandel, Michael Löwy, Daniel Bensaïd, Perry Anderson, and more. And through the work of Palmer, the Minneapolis Teamster Strike is closer than ever to center stage in labor history.

Among the New New Left and millennial socialists (especially the 65,000-strong DSA), one can point to the impact of the “Rank and File” strategy for the labor movement, and statements such as the following by Jacobin editor Bhaskar Sunkara in the Nation: “…at the dinner tables of my childhood friends….I would meekly call myself a socialist…. ‘Like Sweden?’ I would be asked. ‘No, like the Russian Revolution before its degeneration into Stalinism.’”(23)

Such seeds spread far and can grow in unexpected and unanticipated forms. Political clarity and organizational coalescence have yet to flower, but the virtue of volumes such as US Trotskyism is that they might give a hand to the gardening.

Perhaps the facet of Trotskyism’s cultural dimension would have been heightened if the trilogy had included more on literary-artistic issues. While even three volumes can’t include everything, there might have been a dozen pages of creative work by SWP members such as John Wheelwright (his poem dedicated to Trotsky), Sherry Mangan (a “Paris Letter” on surrealism), Sol Babitz, Laura Slobe, George Perle, Duncan Ferguson, Maya Deren, Harry Roskolenko, Trent Hutter (Peter Rafael Bloch), and others, not to mention the debate over the Marxist-modernist journal Partisan Review in the Trotskyists’ Socialist Appeal (or some of Trotsky’s correspondence with SWP members on the Partisan Review editorial board).

Moreover, the narrative history might have made reference to the many cultural figures attracted to Trotskyist youth groups at various times. For instance, while the matter is of no interest to orthodox Trotskyists, the fact that the leading young Trotskyists at UC Berkeley in the 1930s included the gay poet Robert Duncan, the film critic Pauline Kael, and the painter Virginia Holton Admiral (mother of actor Robert De Niro) is indicative of the movement’s on-the-ground appeal to creative radicals.

On the other hand, the same Trotskyist culture contained mindsets more suggestive of religious faith than Marxist science, as can be seen in this 1944 claim by SWP leader Joseph Hansen in the journal Fourth International:

“When the history of our country is written by future historians, they will not look for material in the library at Hyde Park where Roosevelt employs a staff to file away minutiae about himself. They will dig painfully into scattered memoirs, accidental bits written in the heat of struggle, items preserved in the files of Trotskyist publications, to find out what the real figures of American history were like.”(24)

Statements of messianic zeal like this are not much present in the pages US Trotskyism, but they are part of the historical picture of the movement that existed and need to be addressed. At the same time, I should emphasize that the 1960s brought about a diminishment of such grandiose illusions, as can be seen by the fine selection of writings by Hansen on Deutscher, Breitman on Black Nationalism, and Cannon on C. Wright Mills and socialist democracy in Part III.

VII. Grand Predictions

Karl Marx famously warned: “The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.”(25) If that remains true for the Left, the only way out of the nightmare of flawed models is to identify and dismantle the negative legacies in order to understand what went wrong; then, creatively rethink the model — not simply glue it back together.

A principal political fault in the historical writings represented in US Trotskyism flows from a cast-iron certainty about the next phase of history, especially a rapid drive toward social revolution during the late 1930s, and another coming as a surefire result of World War II.

This certainty produced delusions about one faction already possessing the “principled revolutionary program” (a matter of opinion) which only encouraged a rush toward inaccurate understandings of what was happening in the world and among the working class. Next came unrealistic prospects for progress by the SWP as well as the assorted groupings that emerged from it.

Our taking note, in hindsight, of such hyped-up prospects can no doubt provide a context for explaining why some of the faction fights seemed so bitterly urgent to the participants and splits were presented as brave steps forward. Yet the recognition of such causes for zealotry cannot serve as any kind of justification for bad behavior. A larger point must be recognized: Such grotesquely disproportionate expectations flowed from the making of catastrophically ill-informed judgments.

Repeatedly, one finds even the most sophisticated of contributors to these volumes treating history as a teleological process — marching inexorably toward a crisis that will produce the next stepping-stone toward a classless society. A characteristic claim is Cannon’s 1946 prediction, just after the postwar strike wave and on the eve of what we now call “The Golden Age of Capitalism:”

“Our economic analysis has shown that the present boom of American capitalism is heading directly at a rapid pace toward a crisis; and this will be a profound social crisis which can lead, in its further development, to an objectively revolutionary situation.”(26)

Those SWP members who raised questions about projections that seemed out of touch were quickly labeled as pessimists, bending to alien class pressures, and so forth. Marx, in distinction, was surprisingly ambiguous on the topic of teleology, which is why contemporary socialists appropriately treat this kind of thinking with skepticism. We must also ask how Cannon could be so certain of “our economic analysis”; who were the experts, what resources did they have, and why were they taken so seriously?

History has not been kind to grand predictions, although there is certainly nothing unusual about coming up with erroneous generalizations from a contemporaneous political conjuncture as I suspect that Cannon did in this instance. All of us are familiar with the case of Francis Fukuyama, the eminent political scientist who wrote The End of History and the Last Man (1992) after the collapse of the USSR.

On this basis Fukuyama declared the triumph of liberal democracy, moments before separatist passion and ethnic cleansing began to tear through the former Yugoslavia, followed by the dramatic escalation of nationalism, populism, and fundamentalism.

The lesson is that the present generation of socialists, seeking effective political program and strategy, must create safeguards against such thinking through the fashioning of new and appropriate forms of revolutionary optimism and abiding less hubris about our powers of prophecy. Instead of Court Astrologers telling us the best time to rev up the class struggle, we require access to a wide range of expertise that will help us converge on a better understanding of reality.

Can there be an organizational culture that can accommodate the theory and practice of non-teleological Marxism? One would have to have superhuman powers of cluelessness to believe that young radicals can simply start a new revolutionary socialist movement with a blank slate, making an end-run past history. At the same time there can be no toleration of the recycling of old pieties about the “real” Trotskyism or Cannonism never having been tried.

The most productive way to settle scores with the past is to candidly determine what took place and why; and that may mean opening the very doors that others prefer to keep closed. In our pursuit of a culture that can increase the possibility of sound socialist politics, perhaps we should investigate matters such as the following:

• Were the issues resulting in schisms in the SWP impervious to a compromise solution, or were some unnecessarily exaggerated by internal power struggles or profound misreadings of history?

• Were decisions by the membership in heated disputes made on the basis of being fully informed about matters such as the U.S., Soviet, Chinese, or Cuban economies, or mainly a result of loyalty to certain charismatic leaders?

• Was a phenomenon like groupthink (the desire for cohesiveness and fear of ostracism at the cost of critical evaluation) a factor in the organizational culture of the SWP?

• Was the leadership selection process (which put in power white males such as Cannon for 25 years, Farrell Dobbs and Tom Kerry for 15 years, and Jack Barnes for nearly 50) flawed in some way that requires a critical review?

• What was the actual scope of the internal educational system in the SWP and its predecessors? Was there an authentic openness to the newest research in philosophy, economics, and social theory? Or did the highly-selective “Trotsky School” at Mountain Spring Camp, New Jersey, operate more like a Hogwarts with “The Three Laws of Dialectics” in place of magic and wizardry?

Moreover, the entire issue of sexual misconduct, not to mention mistreatment of sexual non-conformists, is absent in these volumes. Did such things simply not exist back then; or was sexism so baked into the culture of the movement that the editors can’t see it? (There is not even a citation of Christopher Phelps’ 2013 prize-winning essay on “The Closet in the Party: The Young Socialist Alliance, the Socialist Workers Party, and Homosexuality, 1962-70,” winner of the Audre Lorde Prize and appearing in a journal well-known to the editors.)(27)

VIII. The Promise of “Dissident Communism”

Let me conclude by returning to the beginning. Why was this trilogy assembled in this particular form? As the general Preface explains, by the late 20th century the traditions of Communism and Social Democracy had become “largely discredited,” so that “would-be revolutionaries” are at this point obligated “to understand what had happened — and also to locate strengths, positive lessons, and durable insights among the failures.”

Something, though, has been missing: scholarship and primary sources about “the dissident currents” of the Far Left. These lesser traditions, together with the more mainstream ones, “have actually had a significant impact upon labor and socialist movements that have been of some importance in the shaping of [our] country’s history.”(28)

To address this deficiency, the trilogy we have just inspected will “provide substantial resources for scholars and — we hope — for activists, but they by no means constitute a definitive account of U.S. Trotskyism.” This approach, modestly placing Trotskyism within a larger context of “dissident currents” complementary to the mainstream Left, advances a methodology that appears to be refreshingly wide angle rather than narrow.(29)

Thus in contrast to the more familiar “red thread” method of Trotsky himself, which insists that Trotskyism is the only true successor of Lenin’s Bolshevism, the trilogy presents this legacy far more humbly as a dissident critique within a larger community. While aspects of the trilogy are not always consistent with this aim, those who want to say “good riddance” to the vitriolic and strident certitude that has plagued so much Marxism-Leninism of the past should welcome the standpoint that Le Blanc proposes in these volumes.

What next? Although there is much to be learned from this documentary trilogy about the efforts of one small Marxist tendency three-quarters of a century ago, it would be irresponsible to sit around celebrating some glorious heritage while the present intervenes in unexpected ways. These tomes are about the past but who can avoid thinking of the present?

As I have tried to demonstrate, there are productive as well as unproductive ways of exploring this history; and there are occasions when we must look deeper at what we think we see. Above all, revolutionary socialism is not a spectator sport and it will be a new activist generation that ultimately determines how we might look back on this material to move us forward. One need not be convinced that there exists some roadmap from the past, but only that there is intelligence to be salvaged for use in our present contest to fashion an alternative future.(30)

For radicals of several generations, and various Left political backgrounds, the question before us now is relatively straightforward: Will the project of building a mass, revolutionary socialist movement devoted to the defense of the international working class come crashing down amidst our disunity and distrust? Or can it be made to rest more strongly on a stable foundation?

Fueling the flames of contemporary resistance and solidarity is the point, but I have raised critical questions about these volumes because that mission requires ever more objectivity and accuracy in our historical reconstructions. Can we be strategically detached, and constructively critical, toward this writing while refusing to be above the fray? Like literature teacher John Keating (played by Robin Williams) in Dead Poets Society, the point is not to perform an elegy but to foster a reclamation of rebel spirits.

Notes

- https://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/16/arts/christopher-hitchens-is-dead-at-62-obituary.html?auth=login-email&login=email

back to text - https://www.channel4.com/news/hitchens-dies-age-62. According to the Guardian, Hitchens was a member of the British Trotskyist group International Socialists from 1966 to 1976. See https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/dec/16/christopher-hitchens-obituary. Other sources quote Galloway as using “popinjay” instead of “lunatic.” Two years later the New York Times gave brief mention to the election of Socialist Alternative member and Trotskyist Kshama Sawant to the Seattle City Council; see “Rare Elected Voice for Socialism,” New York Times, 29 December 2013, Section A, 23.

back to text - Part III, 1.

back to text - Originally, the three-volume documentary history was published in hardback by the “Historical Materialism Book Series” of Brill Academic Publishers in 2017, but it is now available in paperback through Haymarket Books at a much reduced (although still hefty) price.

back to text - Part III, 504.

back to text - https://www.marxists.org/archive/pablo/bio/index.htm

back to text - Part III, 3.

back to text - Part III, 16. These are all well-known African-American political activists.

back to text - Part III, 19.

back to text - I will try to avoid repeating the various analyses of SWP history that I have already provided primarily in Wald, The New York Intellectuals (1987); Le Blanc et al, Trotskyism in the United States (1996); and Wald, “A Winter’s Tale Told in Memoirs,” Against the Current #153 (July-August 2011), available at: https://solidarity-us.org/atc/153/p3317/; and “Bohemian Bolsheviks After World War II: A Minority Within a Minority,” Labour/Le Travail 70 (Fall): 159-86.

back to text - I have met and mostly interviewed the following contributors: B. J. Widick, Farrell Dobbs, George Novack, Felix Morrow, Joseph Hansen, Jean Van Heijenoort, George Breitman, Bert Cochran, Raya Dunayevskaya, Frank Glass, Tom Kerry, Sam Gordon, Michel Raptis, Milton Zaslow, David Weiss, Evelyn Reed, Hedda Garza, Myra Weiss, Fred Halstead, Jean Tussey, and Joyce Cowley. Regrettably, all are now deceased.

back to text - Of course, some writings providing background studies and alternative views on specific subjects are cited in the prefaces and introductions. However, in recommending alternative models, I find that some reader-friendly approaches to the study of primary material are handled more effectively in Albert Fried, Communism in America: A Documentary History (1997) and in the many Pathfinder Press volumes of writings by Cannon, Novack, and Trotsky edited by George Breitman, Naomi Allen, Les Evans, and others.

back to text - Sadly, George Clarke (1913-64) appears as little more than a punching bag in these volumes, although he was a central leader of the Trotskyist movement for nearly a quarter of a century and author of a vast number of writings on political theory and practical interventions. Clarke was an all-around political activist, a superb speaker and educator, who served as a member of the national committee, the organizer of the New York local, national election campaign manager, editor of the Militant and Fourth International, and SWP representative in Canada and Europe. In the labor movement he was an organizer for the UAW in the CIO and served as a merchant seaman in World War II where his ship was torpedoed and he survived in a lifeboat for several days. At the age of 51 Clarke was killed instantly in a car accident. Farrell Dobbs and Felix Morrow gave eulogies at his funeral.

back to text - Part II, 18, 19. Prior to the arrival of C. L. R. James in the United States in late 1938, the main Black activist in the SWP was Ernest Rice McKinney, a former Socialist, Communist, and follower of A. J. Muste who was antipathetic to special demands for African-American workers. A crucial contribution to understanding the 1930s views of Trotskyism on race can be found in Race and Revolution by Max Shachtman (2003), edited and introduced by Christopher Phelps.

back to text - Part I, 7. Variants of this are deployed in the introductions.

back to text - Part II, 3.

back to text - Part II, 20.

back to text - Part II, 342. Van Der Linden’s book is Western Marxism and the Soviet Union (2009).

back to text - This is quoted in https://newpol.org/anticapitalist-strategy-and-the-question-of-organization/

back to text - See Peter Drucker’s Max Shachtman and His Left (1993) for a refreshingly heterodox, sympathetic but critical view of the strengths and failures of Shachtman’s political leadership. See also the informative critique by ATC Managing Editor David Finkel https://solidarity-us.org/atc/57/p2645.

back to text - Part II, 492.

back to text - Shachtman referring to Cannon and his supporters as “A clique with a leader-cult” isn’t very nice.

back to text - See https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/letter-nation-young-radical/

back to text - See https://www.marxists.org/archive/hansen/1944/02/jail.htm

back to text - Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1952): https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/

back to text - Part II, 157.

back to text - Christopher Phelps, “The Closet in the Party: The Young Socialist Alliance, the Socialist Workers Party, and Homosexuality, 1962-70,” Labor: Studies in Working Class History 10, 4 (Winter 2013): 11-38.

back to text - Part I, X.

back to text - Part I, X. A six-volume series edited by Le Blanc is currently in the process of appearing under the heading of “Dissident Communism in the United States.” The Trotskyist trilogy comprises only three volumes; the others include a collection called The “American Exceptionalism” of Jay Lovestone and his Comrades, 1929-40 (2015), about the organized supporters of Nikolai Bukharin who were usually called “Communist Party (Opposition),” and two yet-to-be-published collections that engage “Independent Marxism,” by which is meant those unaffiliated with major political groupings.

back to text - To some extent, that is the key to the success of Howard Brick and Christopher Phelps, Radicalism in America: The US Left Since the Second World War (2015). See my review in ATC #179 (November-December 2015): https://solidarity-us.org/atc/179/p4527/

back to text

September-October 2020, ATC 208