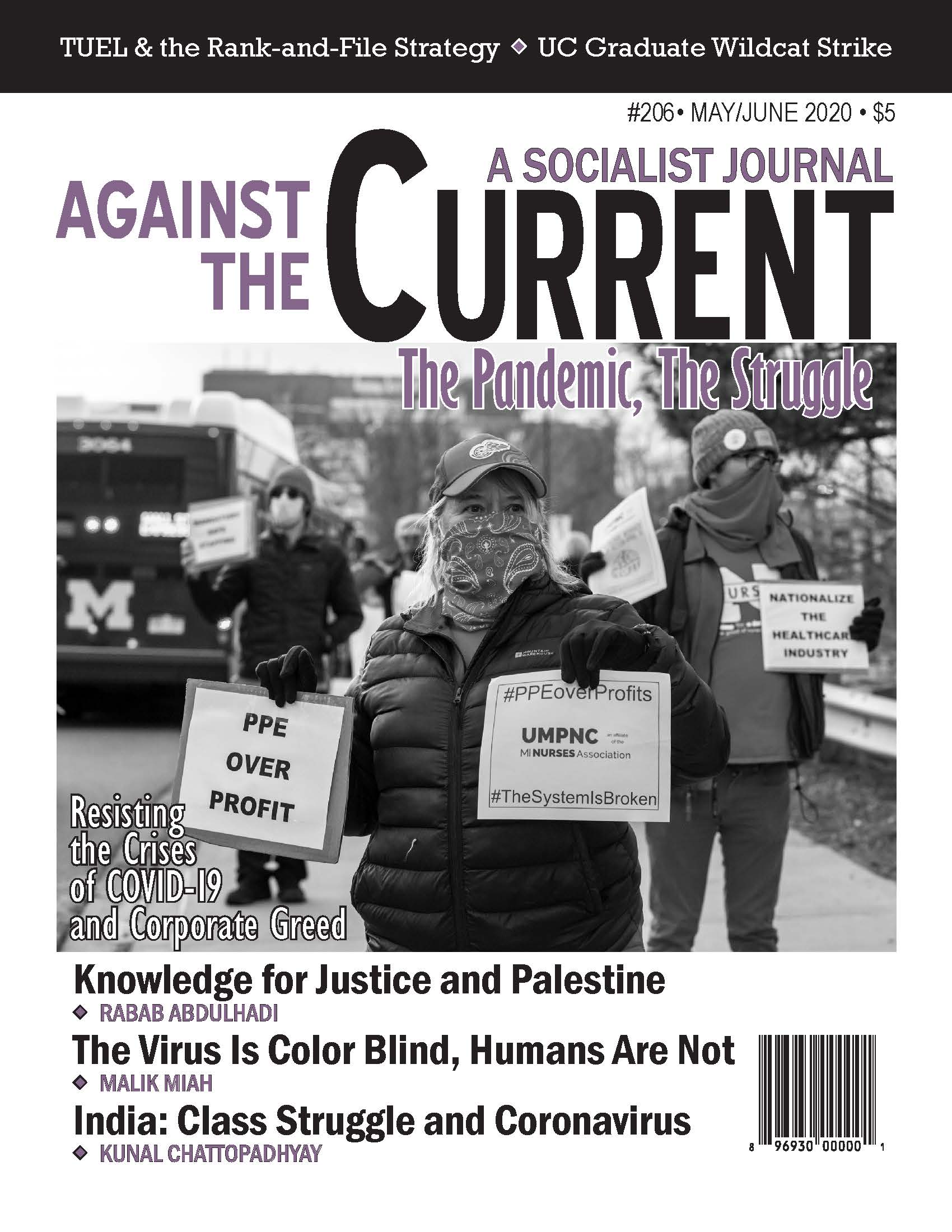

Against the Current, No. 206, May/June 2020

-

A Crisis of Vast Unknowns

— The Editors -

Virus Is Color Blind, Not Humans

— Malik Miah -

UC Graduate Student Workers Wildcat Strike

— Shannon Ikebe -

Two-Tier Response to COVID-19

— Ivan Drury -

Producing Knowledge for Justice

— Rabab Abdulhadi -

On the Delhi Pogrom

— Radical Socialist, India -

Class Struggle and the Pandemic

— Kunal Chattopadhyay -

Introduction to William Z. Foster and the TUEL

— The ATC Editors -

TUEL and the Rank-and-File Strategy

— Avery Wear -

A New Economy Envisioned?

— Dianne Feeley - Reviews

-

A Bitter Class Grudge War

— Rosemary Feurer -

The GI Bill, Then and Now

— Steve Early -

Vagabonds of the Cold War

— John Woodford -

A Problematic Diagnosis

— Michael Tee -

Hidden Deaths in a Long War

— Barry Sheppard -

Hugo Blanco's Revolutionary Life

— Joanne Rappaport -

Karl Marx in His Times

— Michael Principe -

Karl Marx in His Times

— Michael Principe - In Memoriam

-

Gene Francis Warren Jr., 1941-2019

— Ron Warren -

Socialism as a Craft

— Mike Davis

Rosemary Feurer

The Long Deep Grudge:

A Story of Big Capital, Radical Labor, and Class War in the American Heartland

By Toni Gilpin

Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2020, 425 pages, $21.95 paperback.

TONI GILPIN’S THE Long Deep Grudge is a vivid story about the feisty radical union, the Farm Equipment Workers Union (FE) of the Congress of Industrial Organizations and how it took on International Harvester, which fought unions for generations.

The FE had distinct ties to the Communist Party, and some scholars have argued that despite the cost of such affiliations, there was nothing much radical about these CP-dominated unions — that the forces of capital or Party policies tied to a materialist theory of change constrained them and directed them to the center despite the costs of their affiliations.

Gilpin disagrees, makes this a class struggle story, highlights the human element, bringing details from oral histories and buried documents to life. Her compelling narrative is achieved with short chapters that convey the character of people and transformational moments. We can see the power plays from the shop floor, the mansions of the McCormick titans who guided labor policy, even from the reports of the Federal Bureau of Investigation on Gilpin’s Communist father, Dewitt, who became the FE’s publicity and education director.

Gilpin has told this story before, in a 1988 dissertation that has been cited and respected for many years now, but in this version she has brought more drama and narrative force, and aims to make the story relevant for thinking about the role of radicals in labor organizations.

The Long Deep Grudge anchors the story of this twentieth century union to the 19th century battles for unionization, continually reminding readers of the way that the FE leadership saw themselves as part of a tradition that derived from the deadly struggle for the eight hour day and radical visions of the 1880s. The corporate behemoth they took on originated with McCormick Works based in Chicago. Cyrus McCormick thought those who sought to interfere with his shop floor control needed to be targeted, blacklisted and policed.

By the 1880s, Chicago was the center of a socialist and anarchist “Chicago Idea” that thought trade unions were not just instruments for settling a contract, but a possible means to social transformation, toward the cooperative commonwealth. In that context, Cyrus McCormick reacted with his own class war to “weed out” the “bad element.”

So McCormick tied the private profit motive to a larger purpose of eliminating the militant minority. He locked out his workers over union recognition and firing scabs in 1886 in the months before the eight hour day national strike call of May Day. That strike brought anarchist leader August Spies to the doorsteps of the McCormick Works on the morning of May 3, as police clubbed workers, fired revolvers into the mass picket lines, leading Spies, in outrage, to call for “Revenge!” for the deaths that took place.

The rally at Haymarket Square was rather peaceful until a bomb exploded and killed police. McCormick was part of the red-baiting revenge campaign that crushed the eight-hour-day-movement and led to conspiracy prosecution of anarchists, four of whom clearly not associated with the bombing were hanged in November 1888.

As the noose was being tightened around his neck, Spies proclaimed that “The time will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today.”

Long Memories

Gilpin makes a most compelling case that the long memory of the anarchists, and of Spies specifically, influenced the FE activists as well as management. Management might grudgingly accept some mid-20th-century unions, but the kind of challenge the FE presented was something that harkened back to this earlier style.

The FE radicals conjured up the anarchists as founding fathers of their campaign, from the first leaflet in Chicago to organize, to calls for a 30-hour workweek in the 1950s and 1960s. Spies’ words were printed on organizing leaflets, and the Chicago Idea of making unions more than bread and butter instruments informed the approach of the key organizers.

Radicals in the mid-20th century, she argues, were trying to create instruments that might make the union movement capable of taking on the power structures of capitalism. It was more than just heroic inspiration, but a continuation of the struggle to implant radical visions into praxis, both in and beyond the contract. This long arc is usually absent from the stories of the union uprisings of the 1930s.

Organizing International Harvester was tremendously difficult because of the tight reign of management after 1886, and especially after early 20th-century mergers and capitalization made it a premier corporation whose management was still tied to the personal agenda and perspectives of the McCormick family. John L. Lewis, head of the CIO, called organizing Harvester “the hardest job I know of,” and maybe that’s why he allowed CP activists free rein to take it on.

By that time, the company was an extensive multi-plant operation whose tentacles extended well past Chicago into the Midwest. Scholars who have studied Harvester have taken management’s word that it sought by the 1920s to satisfy stockholders and workers, that both interests could be served better without unions.

Cyrus McCormick III established a modern works council and instituted welfare capitalism after World War I, and most histories have acknowledged this forestalled unionization. Lizabeth Cohen’s book on Chicago’s CIO (Making a New Deal) claims these were part of a “moral capitalism” approach that management offered and workers embraced in the 1920s, but these claims are dissected here and found to be wanting, using new evidence from management and other archives.

There was nothing moral about it. The welfare was sniveling and targeted toward a small number of workers, a continuation of the divide-and-conquer strategy. Gilpin shows these modern business approaches were extensions of the effort to weed out the “bad elements,” installing a façade of democracy over a regime of dictatorial shop floor control.

The works councils offered little voice for shop floor value extraction and were better characterized as propaganda pipelines, intended to help management detect and channel dissent. This is important, because without this full picture we will miss the repression at work in the 1920s and 1930s, and then also miss how despite this, organizers were able to undermine the control and surmount the repression.

While Cohen took her cues from labor historian David Brody who held doubts about the potential for radicalism (Making a New Deal barely mentions radicals in Chicago), Gilpin’s discussion of organizing tells the fuller story with the radical organizers left in, and here we see that there was more to it than workers wanting security under the federal government.

Often we harbor notions that solidarity erupted spontaneously in the CIO era, but Gilpin has used the oral histories to show that an activist cadre steadily built workers’ growing confidence that the union movement was worth their while. That there was a strategy to beat the system, and that they wouldn’t be left behind, mattered more than some formula for “moral capitalism.”

Gilpin does not romanticize solidarity, but shows that when radicals took over the organizing drive they sought to carefully and steadily lay the groundwork for centering the capacity of workers. There is no evidence that desire for security was the only possible direction for unions. Radicals’ involvement made a difference. It’s what the McCormicks had always warned against.

At the center of the class war was management’s incentive piecework system, which drove workers to exhaustion under the guise of bureaucratic chains that seemed intractable. The pay rate system (enclosed in secreted black binders) was so complex that workers doing the same job might have vastly different paychecks, without being able to figure out why that was the case.

By the 1940s there were 30,000 piecework prices, for example. Relentless timing and re-timing efforts were designed to capture the energy and knowledge of workers and created antagonism that Gilpin shows to be the linchpin of the union campaign.

The radicals considered the incentive system as daily lessons about surplus value extraction, and turned the shop floor experience into the base for the praxis of solidarity and resistance.

Wartime Gains

The key to organizing was finally taking over the works council and organizing from within as well as the outside, in a steady drip-drip-drip of counter-information. It took until 1938 for the first local to be formed, and until World War II for the union to gain some major victories.

Ironically, it was in the heart of the patriotic moment during World War II that the first contract was signed, and that is usually where narratives suggest the war effort dissolved the class struggle. Gilpin redeems the CP activists from the criticism that they capitulated on behalf of the political alliance with capital on behalf of Soviet Union directives, though it’s pretty obvious there was major kowtowing to the Soviet line.

The base for their radical shop floor campaigns came from establishing — through the War Labor Board cases — the right to democratically control the pace of work and to contest the rate of exploitation. These rulings were in fact centered in the conceptual and evidentiary assistance from FE researchers who contested and dissected every element in order to prevail.

The FE’s researcher Aaron Cantor, only 25 years old at the time, saw the War Labor Board cases as a vehicle for “democratic control over the powers of management relating to the tenure and conditions of work, particularly the disciplinary powers of management.”

This set the stage for the first major showdown of the postwar era when management wanted to roll back these WLB-assisted assaults on the incentive system, while the FE was determined to extend them.

Gilpin quotes FE’s Director of Organization, Milt Burns, declaring that “the philosophy of our union was that management had no right to exist,” and shows it was more than just rhetoric.

Through an energetic strike, the FE secured a contract that provided not only significant wage increases, but most importantly a strong shop steward system that paid stewards for time off to police the plant. This hit Harvester hard, and combined with the assault on surplus-value-extraction, set the stage for later contests in the following years.

Shop stewards sought to communicate the concept of work stoppages as the starting point to building solidarity against managerial attempts to divide, and as daily exercises for empowerment. In addition, the union won plant-wide seniority, which it used to contest vestiges of racist allocation of jobs.

A Study in Contrasts

Gilpin uses the FE’s chief rival, the United Auto Workers, to show the distinction between FE’s radical union style and the dominant form of CIO union strategy. The UAW was led by former socialist (likely a former Communist Party member, as well) Walter Reuther, who rose to power through an iron grip caucus that included a campaign of purging or quieting CP-aligned factions.

Reuther committed to winning long-term contracts, to accepting management’s right to run the plant, extracting cost-of-living benefits in exchange. The 1950 so-called Treaty of Detroit with its five-year contract was a peace plan, and a proving ground for statesmanship over labor conflict that would be tolerated by management more willingly than the FE’s challenging style.

Harvester management continually compared FE to the UAW (there were more than five times the number of work stoppages at FE Harvester plants in the postwar years) and yearned to bring the kind of peace the UAW offered.

Reuther committed the UAW to a “politics of productivity” that accepted management’s right to run the plant, and focused on the contract as a legalistic instrument that cordoned off workers’ demands to contract bargaining rounds. The contract helped to build a bureaucratic apparatus regime that oversaw things and helped extend Reuther’s control as well.

The most notable comparison, though, was the shop steward system: the FE aimed for a ratio of one for every 50 workers or so, and even less if possible. The UAW committeeman system was one for every 250, or even more.

Every day was a bargaining session in this FE conception of the union. The FE promoted settling grievances by striking or other forms of collective action instead of letting the grievance wind its way through a maze of bureaucracy. For the UAW in this period the contract was legalistic, and the grievances were increasingly instruments for a bureaucracy off the shop floor that considered themselves experts on the details of classifications, skill and legalese.

The UAW mastered the art of grievance filing, while the FE believed in immediate resolution, leading to regular job actions that saw them leaving the plant at strategic quickie strikes, engaging in job actions far beyond anything experienced in the UAW. That’s the real way to run a union, even one not tied to farm equipment.

I’d guess that most people who have been in unions will be able to place their own unions’ philosophies along the spectrum that they encounter in the comparison between these unions, even if these were mostly male industrial workers.

Racial Justice for Real

Gilpin also distinguishes the FE from the UAW on the issue of racial justice. While the UAW is well-known for its commitment to civil rights in high points such as the March on Washington, its record in connecting labor rights and civil rights at the local level, especially in the Southern locals, was abysmal.

In contrast, when Harvester management plotted a course of escape from FE union contracts by establishing a large plant in Louisville, Kentucky, the FE immediately followed, and racial justice was at the center of their conception of reordering power. Shortly after winning recognition, the union launched a strike to eliminate the differential and came close to that goal.

Gilpin’s account contests Jennifer Delton’s writing on Harvester for racial integration (Racial Integration and Corporate America, 1940-1990), showing through these oral histories and other sources that it was instead a hard-won fight by the workers that deserves the most credit. Gilpin uses the case of FE Local 236 to explain how workers could be radicalized on the issue of racial justice through the shop steward system described above, to move to a broader kind of solidarity that included racial justice.

Soon, leaders like African-American Jim Wright, whose commitment to the union was built through the pledge of the FE to interracial justice, was leading community campaigns in Louisville to desegregate parks and a hospital.

While Harvester jobs were mostly male, these campaigns brought women into the union movement as well. Such campaigns also built an allegiance to the union that allowed it to withstand the anti-Communist raids that seemed a yearly concern.

Defeat and Forced Surrender

Despite the gains that the FE made through militant representation at the point of production, Gilpin writes a cautionary note about how management also took advantage of the union’s zealous contentiousness at the point of production.

Capitalists are always on the alert for opening salvos in their class war to reign in their adversaries, and the interviews in this book show precisely the limits of such activism when capital simply doesn’t recognize the radical union’s right to exist.

It turns out that by the 1950s, Harvester management was provoking these shop floor struggles in order to shut down production and to wear workers down. There were some wise shifts in strategies from the FE in response, including slowdowns instead of work stoppages, but such strategic miscalculations by union leadership bled into a disastrous 1952 strike.

The union seemed to think they could prevail in a bracing mass picket-line campaign, but instead they were handed a massive defeat despite occurring amidst the escalating Cold War and red-baiting.

Having sought refuge against the UAW attacks by merging briefly with the United Electrical Workers union, by 1955 the top leaders of the FE collectively turned tail and made the decision to exit into the arms of their enemy, the UAW. They bargained for union positions (though some refused, and a few locals in Chicago stayed in the UE). This they did against the counsel of the CP leaders.

The question of whether the FE might have done a disservice to the workers’ movement by refusing to struggle on with the UE, which did survive, is a question Gilpin doesn’t care to address. It was the UE which revived the sit-down in recent years at Republic Windows & Doors, a reprise of the FE’s actions at Harvester’s Twine Shop in the 1950s, winning severance just in the same way, but also sparking the imagination of trade unionists across the United States.

There are counterfactual speculations among some scholars that an alternative course might have built a labor federation that could have harnessed the 1970s upheavals. Nevertheless, we see step by step in Gilpin’s portrayal, that Cold War politics shouldn’t lead us to view the ultimate victory of the UAW as an endorsement for the conservative approach to labor relations.

The factionalism of labor, jurisdictional boundaries and Taft-Hartley created the means of taming the possibilities for a struggle-based unionism in this major industry. And the capitulation of the FE to the UAW only added to the ultimate advance of the Administration Caucus which has ruled the UAW ever since, with disastrous consequences in the present.

There were some sparks of fire that carried over into the UAW. Those sparks carry deep irony as the UAW has continued to be dogged by the legacy of Reuther’s calculations. Gilpin notes that as the Harvester plants in Chicago began to shut down in the 1950s through the 1970s, her father, now a UAW representative, was a lonely voice calling for a movement for a shorter work week without a reduction in pay, bringing forth the memory of the anarchists’ strategy of the 1880s.

International Harvester of course could ignore such calls, given that they had won the war of position. Within a generation, International Harvester would be gone, and the industry then would be led to its own demise by other players even more ruthless than Harvester management, intent on ramping up the extraction of surplus value to new levels.

Recovering a Radical Legacy

Gilpin’s book is the most engaging and accessible among a growing list of histories of the so called CP-dominated unions. Scholars have established that these unions built more democratic structures, including vibrant shop steward systems, than other CIO unions. They thought about how to contest the power dynamics of capitalism, even if they were uneven on the issue of managerial prerogatives.

All of them in one way or another were influenced by the styles of organizing and strategizing, formulated by William Z. Foster, based on the lessons of the steel strike of 1919, and expanded upon by the experiences of the 1920s and ’30s. [On this history, see articles by Avery Wear in this issue of Against the Current and previously in the November-December 2019 issue — ed.]

Radicals who were committed to making the union a force for social transformation, whatever the injunctions of the Soviet Union, still had to struggle to connect a vision of radical beliefs to the day-to-day organizing and strategies of the workplaces they inhabited. They learned from each other and often connected labor and community concerns and labor and civil rights.

So while these studies recognize the problems and liabilities of the CP, they emphasize the contrast with other CIO unions and with the AFL. The 30-hour work week was promoted not only by the FE, but also for example by the UAW’s Ford River Rouge CP-dominated local, and the UE was still pushing this from the 1940s to the 1960s.

Collectively, these studies show a possible distinct path toward organizing the South, the clearest problem for labor in this era and one that still dogs organized labor and our political possibilities. These studies have confirmed a difference in these unions’ approach that might have led to a different path without the intensity of Taft-Hartley and the Cold War, or the liabilities of the CP.

In the war of position, any union movement of the future will look to these moments to think of ways to undermine the authority of capital at the point of production and in the political economy. Even those that don’t make harvesting equipment.

It’s clear that in our present moment, with most unions still embedded in the politics of productivity, alternative paths are welcome. The leadership of unions themselves were a contributing factor to the extension of capital’s power because they had given up on the issue of managerial prerogatives and continued to steer workers into a political and legal solution in the years of tumult.

As more surplus is extracted, whether in the public or private sector, the issues that industrial workers once confronted are still as relevant as ever. If we are ever to take on capital effectively, we will have to include questioning who controls us, and connecting unions to solutions about how structures of power dominate our lives.

May-June 2020, ATC 206