Against the Current, No. 205, March/April 2020

-

All the Wars: No End, No Point?

— The Editors -

Immigration: The Public Charge Rule

— Emily Pope-Obeda - Siwatu Salama-Ra Is Free!

-

Moms 4 Housing Struggle

— Isaac Harris -

Why the Right-wing Populist Upsurge?

— Val Moghadam - Notes to Readers

- The Torture of Chelsea Manning

-

The Fallacies of Geoengineering

— Ansar Fayyazuddin -

Markets & Private Sector: View from the Farm

— John Vandermeer -

Trump-Netanyahu-Apartheid Plan

— David Finkel -

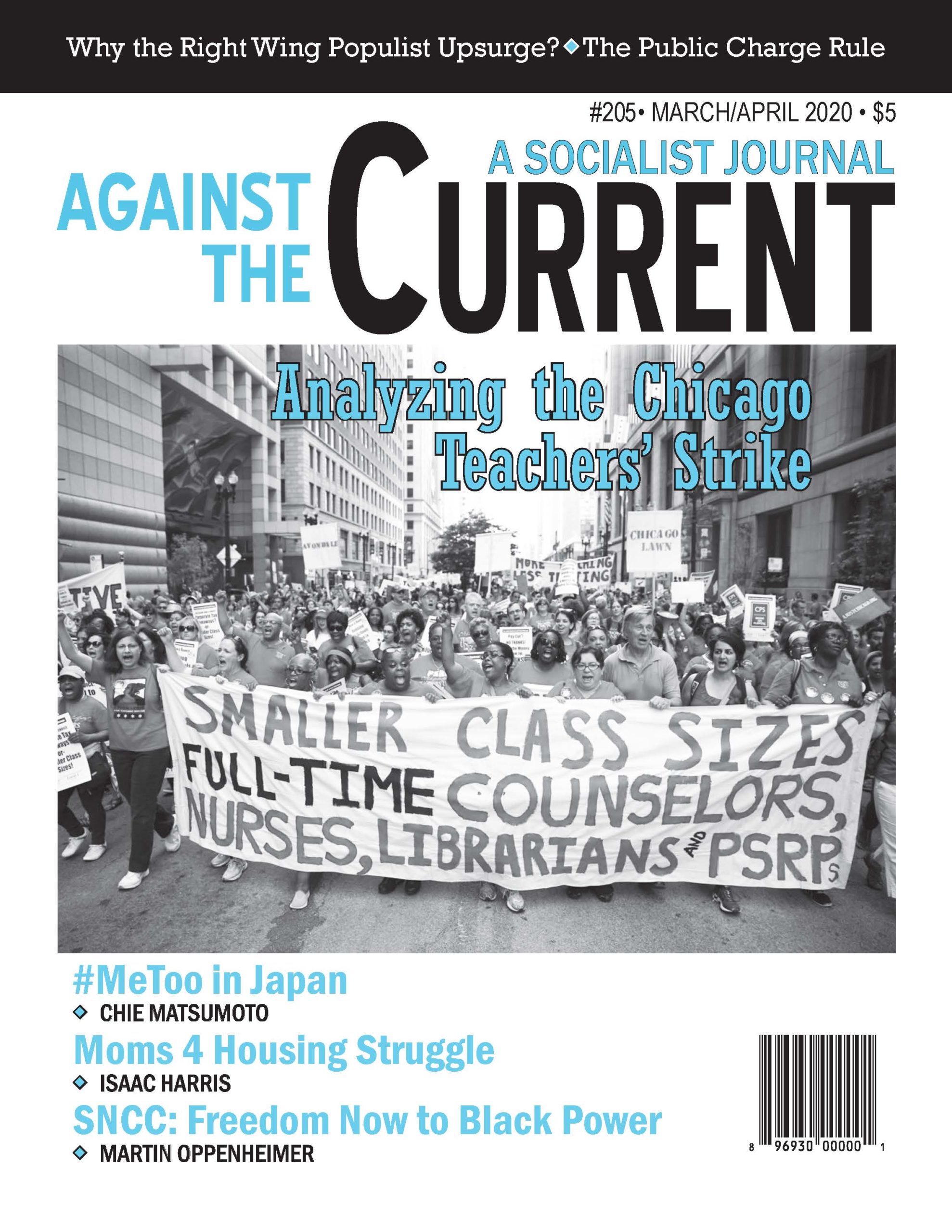

Chicago Teachers Strike, Win

— Robert Bartlett -

SNCC: Freedom Now to Black Power

— Martin Oppenheimer - Feminist Theory and Action

-

#MeToo in Japan

— Chie Matsumoto -

Looking at Social Reproduction

— Cynthia Wright - Reviews

-

Burning Questions of Our Planet

— Steve Leigh -

A Voice of Resistance Revisited

— By David Finkel -

Decaying Teeth, Decaying System

— Rachel Lee Rubin -

Escaping the Debt Trap

— Michael McCallister -

Class, Race and Elections

— Fran Shor -

Surveillance Capital & Resistance

— Peter Solenberger - In Memoriam

-

Margaret Shaper Jordan, 1942-2020

— Dianne Feeley & Johanna Parker

Emily Pope-Obeda

SINCE THE 19TH century, federal immigration policy has centered on determining which immigrants are “desirable” or “beneficial” to the nation. The “dependent” immigrant has been one of the most contested subjects in immigration policy across American history. In thousands of individual cases, the meaning and boundaries of the category “likely to become a public charge” and the accompanying “becoming a public charge within five years of entry” have been fiercely debated.

Although it has received less attention in recent years than immigration control around rationales of crime or unauthorized border crossing, the use of the immigration bureaucracy to police poverty and dependency among foreign-born residents has been an enduring feature of the state.

For roughly a century and a half, the question of what constitutes the “description of a man [or woman] likely to become a public charge,” has been central in immigration enforcement, both for barring migrants at the point of entry, and for enacting post-entry removals.

In 1928, the attorney for Russel Conrad submitted a brief in his client’s deportation case, arguing against a number of the claims of the government, including its application of the “likely to become a public charge provision.”

Conrad, who was identified by the government as being a 33-year old Canadian native of the “Dutch race,” was accused of having sustained an extramarital sexual relationship with an American-born woman. After traveling from Detroit to Windsor, Canada with her, he was arrested upon reentry and charged with having imported a woman across the national border for “immoral purposes.”

But amidst the attorney’s attempts to defend his client’s sexual activities lies a remarkably revealing set of statements about the additional accusation that Conrad was “likely to become a public charge.”

His lawyer focused extensively on the physical qualifications Conrad possessed to be a productive laboring member of society, citing his age, weight, and health record.

Furthermore, he explained, Conrad came from a “people noted for their thrift and virtues and economy” and was “willing and able to do any honest labor no matter how arduous the task might be.” He went on to query, “Is this the description of a man likely to become a public charge?”

The attorney’s efforts to portray Conrad as the perfect, compliant, able-bodied wage-laborer were telling enough. But what followed this question was even more striking and named the tacitly accepted policy among immigration officials regarding the use of the “likely to become a public charge” provision.

He stated: “I understand that this is a charge used largely by the Department to cover that class of cases where the general good of the nation will be best served by the deportation of an individual.”(1)

Draconian Interpretation

Ninety years after the case of Russell Conrad, the Trump administration proposed the most draconian interpretation of that clause the government has ever taken. In late January 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the case of Department of Homeland Security, et al. v. New York, et al., allowing the government’s new public charge rule in immigration proceedings to take effect.

The rule, initially scheduled to take effect on October 15, 2019, had been stopped by multiple federal injunctions, but as of January 27th DHS has been permitted to implement the rule everywhere except the state of Illinois (where a new, more limited injunction still holds).(2)

The new rule, originally announced in October 2018 and made final in August 2019, directs the inadmissibility (both for those seeking entry or those seeking adjustment of status to receive a green card) of potential immigrants based on a variety of expanded criteria. It adds a range of public benefits as grounds for inadmissibility which have never before been deemed as evidence of likelihood to become a public charge (LPC).

Immigrants will be assessed for inadmissibility under the new rule based on a “totality of circumstances,” to include not only their employment, assets, credit report and access to private medical insurance, but also their age, health, education and language proficiency.

While the existing guidelines for LPC status have been applied only to those individuals primarily dependent on cash assistance or long-term institutionalization, the new criteria would be far more encompassing, covering recipients of an array of benefits, including healthcare, housing, and food assistance, such as SNAP, Section 8 housing, or Medicaid.(3)

While much of the critique of the Trump administration’s immigration decisions has focused on his policies toward undocumented or otherwise unauthorized immigrants, the new rule targets so-called “legal” immigrants (although it exempts refugees, asylees, or U or T visa holders).

In addition to those seeking entrance to the United States, it will also apply to nearly 400,000 immigrants seeking to adjust their status, according to DHS. Immigrants who have used the designated benefits for 12 months within any given 36-month period (with each benefit counting separately as its own month) will be considered public charges under the new criteria.

There are very few benefits not included in the ruling, some of the notable exceptions include benefits received by active duty military members, Medicaid for pregnant women or children under 21 years of age, and emergency medical care.(4)

Devastating Consequences

While the case has yet to be decided on its merits at the highest level of appeal, the Court’s January ruling determines that the injunction delaying its application will be lifted. The news comes as a devastating blow to immigrants and immigration rights activists around the country, who have condemned the rule as a “wealth test” for immigration.

Advocates have deemed the new law both a distortion of the original legal intent of the “public charge” provision in immigration law, and a cruel and calculated attack on working-class immigrant communities.

The ruling will not only lead to increases in barred admissions and deportations, but as many advocates have pointed out, it will (and already has) dissuaded many immigrants from seeking needed assistance.

An Urban Institute study found that roughly one in seven immigrant adults reported their family had decided not to participate in a benefit program out of fear of risking their status in the future.(5)

For the Trump administration, this ruling has been hailed as a victory. When the rule change was announced in August, Acting Secretary of Homeland security Ken Cuccinelli fielded questions about its inconsistency with historic American practices and values. His responses garnered significant controversy, particularly when they challenged a much-cherished stanza of American poetry.

While many would be unable to cite its source or author Emma Lazarus, the lines inscribed upon the base of the Statue of Liberty “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free” — are among the most recognizable words of poetry for many Americans.

When asked whether these iconic lines were part of the “American ethos,” Cuccinelli responded “They certainly are: ‘Give me your tired and your poor who can stand on their own two feet and who will not become a public charge… That plaque was put on the Statue of Liberty at almost the same time as the first public charge was passed — very interesting timing.”(6)

The declaration of the United States as a “nation of immigrants” is among the most frequently parroted ideals of the nation, despite its attendant erasure of indigenous peoples and the forced migration of enslaved Africans. Nearly as ubiquitous is the idea of America as a land of opportunity, where the impoverished of the world might find a new start and economic advancement.

Yet such an ideal has been under siege.in immigration law from the start. The sentiment behind Cuccinelli’s words is callous and discriminatory, but his point regarding the timing is factually true — when Emma Lazarus penned these momentous lines in 1883, with their symbolic embrace of the poor, the United States had only a year earlier instituted the first public charge criteria in immigration law.

“Public Charge” in History

The “public charge” provision was enshrined in federal immigration law at its very inception, and has been a major force in immigration control ever since. In 1882, the law initially excluded “any convict, lunatic, idiot, or any person unable to take care of himself or herself without becoming a public charge.”

Within a decade that had expanded, with the 1891 Immigration Act adding a clause for “any person likely to become a public charge.” In 1903, a provision was added allowing for deportation within five years of entry for those who had become a public charge since their entry — but notably, only in cases where it could be proved that they had become charges for “causes existing prior to landing,” which severely limited the numbers who could be removed. Immigrants were required to affirmatively prove that their conditions had arisen subsequent to entry.

Throughout this period, decisions at the point of entry about an individual’s likelihood to become a charge were made based on whether they arrived with money (and how much), whether they had an occupation and viable job prospects, and whether they seemed to be able-bodied and physically healthy.

In addition to single women, who were often assumed to be unable to support themselves by their own labor, those with weak, disabled or otherwise “non-productive” bodies were frequently restricted on this basis.

The clause for post-entry deportations for public charge status was primarily used for those institutionalized in facilities such as hospitals or asylums, rather than those who merely availed themselves of various forms of social benefits.

As historians have noted, those who had become dependent as a result of economic conditions during the 1930s Great Depression were not technically removable, even when reliant on public assistance — leading to the widespread use of non-official “repatriation” efforts to enact mass removals of Mexican immigrants during the period.

In spite of the on-paper limitations to its application, early 20th century immigration authorities made eager use of the provision, often enforcing it with a vigor that did not necessarily match the legal intent of the law. The numbers of removals for the LPC clause were high in proportion to the overall removals during the period, especially in the 1910s and 1920s.

In 1921, for instance, more than a quarter of all post-entry deportations — 1293 out of 4517 total — were conducted on the basis of the charge.(7) And for much of the period, exclusions at the point of entry for LPC comprised a majority of those barred from entry. Still, in the first decades of the century barred and deported immigrants still made up only a very small percentage of the total admittances to the country.

The Uses of Immigration Law

Over the course the 20th century, although still used in significant numbers to bar and deport immigrants, the public charge provision still did not apply to most kinds of relief and government assistance. Through the 1960s, both authorized and unauthorized immigrants were eligible for federal public benefits.

In the 1970s, undocumented immigrants were gradually restricted — from SSI in 1972, Medicaid and AFDC in 1973, Food Stamps in 1974, and federal unemployment insurance in 1976. Under the 1996 “welfare reform” legislation, lawful immigrants lost access to certain federal public benefits for the first time.

Yet even under the most recent prior government issuance in 1999 of a definition of the public charge, most benefits would not render an individual vulnerable to inadmissibility. Instead, it defined a “public charge” explicitly as someone who was “primarily dependent on the government for subsistence,” either through cash assistance or long-term institutionalization.

In view of this long history of criminalizing immigrant dependency, it’s unsurprising that the Trump administration is taking this a step further — changing perhaps from the spirit and letter of the original law, but not necessarily from the social functions it has served over time.

So what has the LPC meant, as a historically enduring feature of American immigration policy? The evolution of the “public charge” provision in immigration policy clearly illustrates a central reality of American immigration history.

Immigration serves an indispensable role in modern capitalism by ensuring the ready supply of low-wage labor. But at the same time, immigration law has evolved to serve business interests by ensuring that those who do not fit the labor needs of the nation can be readily expelled.

The image of the able-bodied, independent (male) immigrant has been a staple of American discourse. Those who deviated from this idealized body that would give to the economy without demanding from the state have long been unwelcome in the country.

Global capitalism relies upon the mobility of impoverished foreign labor — created in no small part by the American subordination and destabilization of foreign economies — and then enacts mechanisms to punish the impoverished poor who do exactly as the economic system dictates they must in order to survive.

As President Johnson stated in signing the 1965 Immigration Act, which fundamentally restructured American immigration in the decades that followed, the test for future immigrants would be: “Those who can contribute most to this country… will be the first that are admitted to this land.”(8)

By stripping one of the last vestiges of government obligation to its non-citizen residents, the administration is further solidifying a system of profit maximization from foreign-born labor to which politicians have long aspired — a system where immigrants can only contribute, but not withdraw from the state (upon penalty of expulsion).

As political debate in Europe becomes increasingly dominated by anti-immigrant, racist rhetoric, there too dependency and public benefits have become central facets of nativist claims.

Even in those nations where the idea of a robust network of social benefit programs has been historically prized, the line is being drawn ever more firmly, delineating that the benefits of membership in a society are to be enjoyed exclusively by citizens.

Racialized Enforcement

In addition to punishing immigrant poverty, the new rule, as critics have pointed out, will disproportionately impact people of color as well as people with disabilities, furthering the existing discriminatory impacts of American immigration policy.

The new rule, while a sharp legal departure from precedent, is not quite as acute a turn from the sentiment (or the on-the-ground enforcement) of previous policies, which have long stigmatized foreign-born poverty, and created a racialized and gendered association between certain migrant groups and the idea of “dependency.”

Alongside the anti-Black welfare rhetoric which has existed for many decades, the idea of immigrant poverty and the depiction of immigrants as “takers” has been a consistent feature of the discourse linking dependency to communities of color.

The public charge provision in immigration law has always had a racial dimension, even while the clause itself did not designate racial criteria. The overzealous application of the law frequently operated along racial lines, and Mexican and Afro-Caribbean immigrants have often the most vulnerable to poorly-substantiated charges of dependency.

Because the vague language of the charge left so much room for discretion, it allowed local examining officials on the ground, medical inspectors, and institutional employees to determine eligibility for the provision around their own prejudices.

In doing so, they furthered popular presumptions about the connections between race and dependency. As Natalia Molina explains about the targeting of Mexican immigrants for deportation in the early 20th century: “The LPC charge… was another mechanism for marking Mexicans as outsiders. Just as the welfare state was being solidified under President Franklin Roosevelt, the LPC label reinforced stereotypes of Mexicans as charity seekers, dependent and underserving of state resources…”(9)

The continued power of those stereotypes could be seen in one of the most notable controversies over the extension of public benefits to immigrants — the fight over Proposition 187 in California. Among other provisions Proposition 187 set out to bar undocumented immigrants from access to welfare and other non-emergency services. It passed on the ballot, and although subsequently overturned by the courts was an important predecessor of the 1996 laws which would bar federal welfare benefits to most lawful immigrants who had lived in the United States for less than five years.

As scholars and advocates have noted, Prop 187 was deeply motivated by racist perceptions about recent immigrant populations, particularly those from Mexico. As Robin Dale Jacobson argues, in the rhetoric around Proposition 187 Mexicans were “raced as takers,” and understood to be “lacking independence,” making them “anti-American” in the eyes of many.(10)

Gender Coding

Debates over immigrant benefits have not only had deeply racial overtones throughout history. They have also been intensely gendered. Historically, dependency — both foreign-born and domestic — has been coded as a female trait (and subsequently deemed all the more threatening when occurring among men).

As Margot Canaday explains of the early public charge provision: “Most fundamentally, the clause was a feminized provision that was commonly used against women… single women were almost by definition public charge aliens.”(11)

In a system in which self-sufficiency and self-government were seen as the purview of men, dependency was seen to be the natural state for women, rendering them automatically suspect as potentially productive laboring immigrants.

Because a “desirable” immigrant and potential future citizen was constructed as an able-bodied male body who would be able to appropriately sell his labor power, those who for varied reasons did not conform to this image were seen as potential hindrances to the efficient functioning of migration under modern capitalism.

Throughout history, claims about female dependency have also intersected with racist anxieties around immigrant birthrates and successive scares about the “unrestrained reproduction” of women of color. During the early 20th century, black immigrant women, particularly from the Caribbean, were often put into deportation proceedings for likelihood to become a “public charge” in which authorities focused on their sexual improprieties, illegitimate pregnancies or “loose morals.”

The hearing and conclusions of the officials in the 1924 case of Hilda Christian, a 25-year-old black immigrant from Antigua, centered around her perceived promiscuity and reproductive threat, although the case was officially decided on the basis of her status as “likely to become a public charge.”

The officer in charge of her case explained that “Since this alien has had two illegitimate children she has shown a propensity to disregard the moral law and consequently it is probable that she may have another illegitimate child and at such time would undoubtedly again become a public charge.”(12)

Although there was no evidence that she was unable to support her current children, the presumption that she would have another — a presumption which revealed official’s beliefs about black women’s unrestrained reproduction — was enough to condemn her to removal.

Christian’s case, along with many others like it, has demonstrated the power of the state to condemn and castigate immigrant women’s sexuality through ostensibly neutral criteria for deportation such as the LPC provision.

What Comes Next?

As the public charge rule continues to work its way through the courts, we have yet to see what the impact of this major departure from legal precedent around the use of the LPC provision in immigration law, although it is clear that it has already begun to harm immigrant families who are too afraid to seek needed support.

We can certainly see the continuation and exacerbation of a longstanding racist discourse around immigrant dependency and access to public benefits, which sharply highlights the cold economic logic behind our immigration policy.

Notes

- File 55636/883, Record Group 85, National Archives and Records Administration.

back to text - Immigrant Legal Resource Center.

back to text - Inadmissibility on Public Charge Grounds Rule, Federal Register, August 14, 2019. https://www.federalregister.gov/uents/2019/08/14/2019-17142/inadmissibility-on-public-charge-grounds.

back to text - Inadmissibility on Public Charge Grounds Rule, Federal Register, August 14, 2019. https://www.federalregister.gov/uents/2019/08/14/2019-17142/inadmissibility-on-public-charge-grounds.

back to text - Hamutal Bernstein, “With Public Charge Rule Looming, One in Seven Adults in Immigrant Families Reported Avoiding Public Benefit Programs in 2018,” May 21, 2019 https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/public-charge-rule-looming-one-seven-adults-immigrant-families-reported-avoiding-public-benefit-programs-2018.

back to text - Devan Cole and Caroline Kelly, “Cuccinelli Rewrites Statue of Liberty Poem to Make Case for Limiting Immigration,” CNN, August 13, 2019.

back to text - Annual Report of the Commissioner General of Immigration (Government Printing Office, 1921).

back to text - President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Remarks at the Signing of the Immigration Bill, Liberty Island, New York, October 3, 1965, LBJ Presidential Library.

back to text - Natalia Molina, “Constructing Mexicans as Deportable Immigrants: Race, Disease, and the Meaning of ‘Public Charge,’” Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 17:6 (2010), 658.

back to text - Robin Dale Jacobson, The New Nativism: Proposition 187 and the Debate Over Immigration (University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 76.

back to text - Margot Canaday, The Straight State: Sexuality and Citizenship in Twentieth-Century America (Princeton University Press, 2009), 25-26.

back to text - File 55,227/788, Record Group 85, National Archives and Records Administration.

back to text

March-April 2020, ATC 205