Against the Current, No. 204, January/February 2020

-

Hope in the Streets, continued

— The Editors -

On the Coup in Bolivia

— Bret Gustafson -

Canada's 2019 Election

— Paul Kellogg - Students in Pakistan

-

Introduction to H. Chandler Davis

— Alan Wald -

Speaking Up in Ann Arbor

— H. Chandler Davis -

Beyond the 2019 UAW Negotiations

— Dianne Feeley -

100 Years of U.S. Communism

— Alan Wald -

Introduction to Socialist Perspectives on the 2020 Elections

— The Editors -

Socialists and the 2020 Election

— Linda Thompson and Steve Bloom - Black History

-

How Race Made the Opioid Crisis

— Donna Murch -

The Pursuit of Truth in the Delta

— Paul Ortiz -

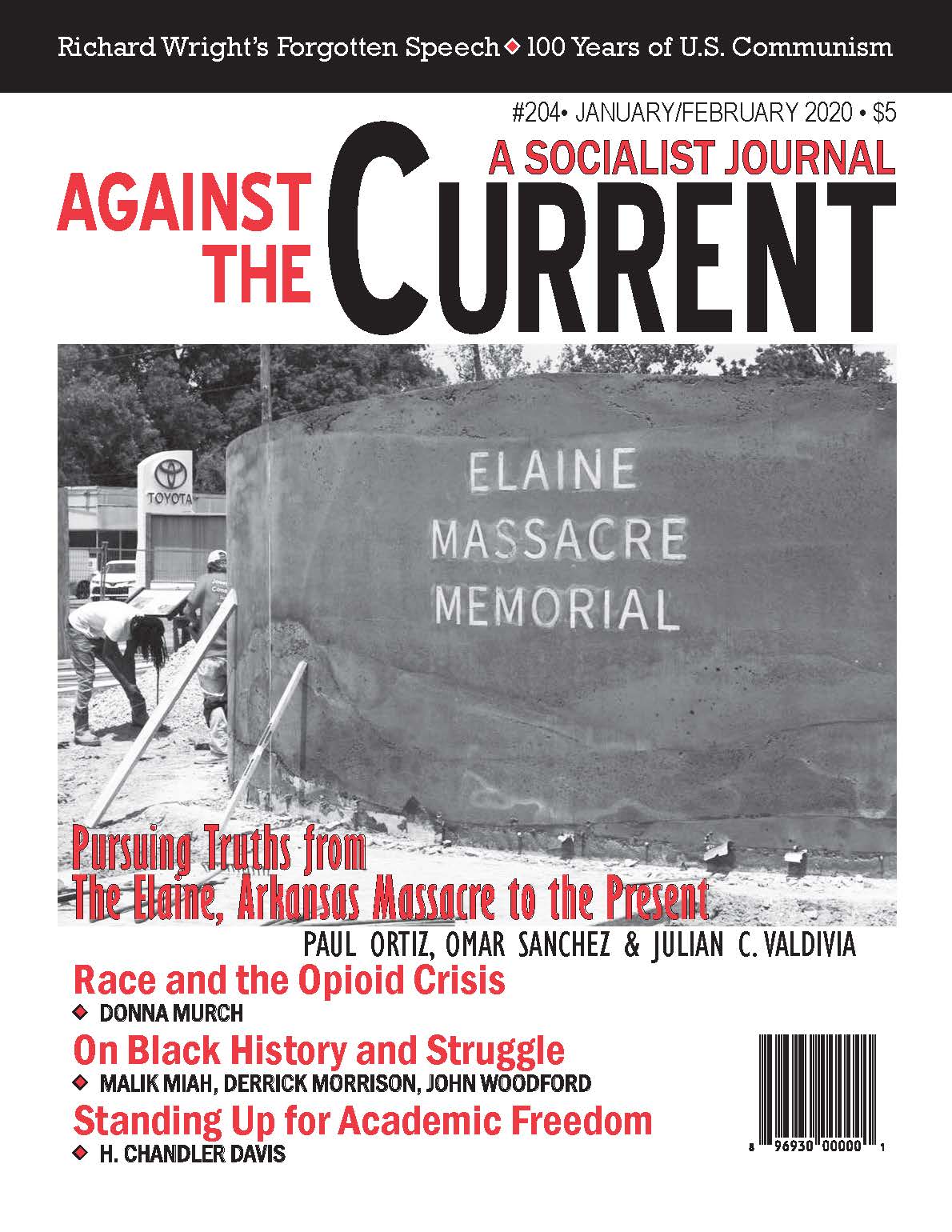

1919 Elaine Massacre

— Paul Ortiz -

Discrimination in the Delta

— Julian C. Valdivia -

A Freedom Odyssey

— Omar Sanchez -

Introduction to Richard Wright's Forgotten Speech

— Scott McLemee -

Such Is Our Challenge

— Richard Wright -

"Not racist" vs. "Antiracist"

— Malik Miah -

A Chronicle of Struggle

— Derrick Morrison -

Justice Denied

— John Woodford - Reviews

-

Latin America's Caldron

— Folko Mueller -

Syria's Unfinished Revolution

— Ashley Smith -

The Power of Gulf Capitalism

— Kit Wainer -

Lawyers of the Left

— Barry Sheppard

Folko Mueller

Making the Revolution

Histories of the Latin American Left

Edited by Kevin A. Young

Cambridge University Press, 2019, 318 pages, $30 paperback.

Voices of Latin America

Social Movements and the New Activism

Edited by Tom Gatehouse

Monthly Review Press, 2019, 300 pages, $32 paperback.

LATIN AMERICA HAS been subject to oppression and exploitation for over 500 years. Naturally, this has continuously spawned resistance on both individual and collective levels. Some of the earliest rebellion dates back as early as the 1500s.

The Inca emperor Manco Inca, for example, started a rebellion against the Spanish Conquistadors in 1536 in Cusco. Although ultimately driven into the remote jungles of Vilcabamba, he and his forces were able to establish a liberated zone and declare a neo-Inca State that lasted for several decades until the execution of his son Túpac Amaru in 1572.

The naked aggression of outright colonialism and imperialism has subsided to only slightly more subtle ways of foreign intervention, as the most recent coup against Evo Morales in Bolivia indicates. The neoliberal economic onslaught of the last three decades has had a devastating effect across Latin America.

While the implementation of NAFTA, for example, did lead to some job creation in Mexico, particularly in the maquiladora and informal sectors, it hit the agricultural sector extremely hard. Small and subsistence corn and bean farming, a very poor and vulnerable segment of society, was decimated by a 1.3 million job loss, as U.S. government-subsidized corn hit the Mexican market.

In addition, there are plenty of native examples of exploitation and violence, both verbal and physical. The current president of Brazil Jair Bolsonaro and his cronies are only the latest representation of this. They are outspoken homophobes and racists as well as open admirers of the Brazilian military dictatorship which ruled the country from 1964 to 1985.

Making the Revolution and Voices of Latin America discuss the social movements that are tackling the issues of oppression and exploitation across various countries in Latin America. They come from rather different angles.

Making the Revolution, published by Cambridge University Press, takes a more scholarly approach and (re-) examines historical movements of the Latin American left, mainly based on academic research.

On the other hand, Voices of Latin America, from Monthly Review Press, is a very timely and current book (despite the most recent election results in Argentina) in that it addresses very recent resistance against the center-right to far-right regimes, following the ebbing of the so-called pink tide (center-left and left-wing governments that ruled a number of Latin American countries in the early 2000s).

Making the Revolution

The self-stated goal of Making the Revolution is to rectify the simplistic portrayal of the Latin American left, set by earlier treatments of the subject.

An often used stereotype portrays a movement of affluent urban and westernized youth who want to impose foreign dogmas on marginalized sectors of the population. This argument is used particularly when it comes to the indigenous sector, somehow accusing the organized left of behaving implicitly racist and/or class reductionist.

Ironically, this argument itself contains a good deal of those two elements. Making the Revolution seeks to challenge this narrative by unearthing pieces of history that provide counterexamples and show how diverse and at times controversial the movement really was.

Edited by Kevin A. Young, the book seeks to do this in a non-binary way. Rather than only focusing on organized labor and political parties of the left or strictly looking at more identity-based groups such as the indigenous or feminist movements, the collection of essays is looking for instances where synergies and collaboration between these historical actors existed.

It does so through 10 independent essays that roughly span 60 years of the 20th century, from the mid-1920s to the late ’80s. Four major periods in the left’s history are covered: 1) the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, 2) the Popular Front and early postwar period of 1935 through the early 1950s, 3) the aftermath of the 1959 Cuban Revolution and 4) the wave of civil wars in Central America in the 1970s and 1980s.

The essays are presented in chronological order, and each essay focuses on one geographic region and experience during a particular period.

The book starts with an essay on the Chantaya Rebellion, a massive agrarian revolt in southern Bolivia in 1927, where an alliance between urban Socialist Party members and rural indigenous communities, based on a shared commitment to rural education, communal land ownership, and redistribution of wealth and power, rocked the mining and agrarian capitalist elites.

While ultimately defeated, this uprising brought about major state reforms in its aftermath and inspired other urban-rural alliances. The author of the essay, Forrest Hylton, associate professor of Political Science at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Medellin, explains:

“Given the miscommunication and distrust that divided indigenous-peasant movements from workers in Latin America between the 1930s and 1980s, the Chantaya rebellion deserves close scrutiny. The revolt failed to become a revolution due to fierce repression and the absence of a complementary insurrection by urban artisans, as well as its limited scale. But Chantaya nonetheless had national, and even international repercussions.”

Making the Revolution concludes with an essay set during El Salvador’s civil war of 1979-1992. In essence, it is a brief history of the group AMES, short for Asociación de Mujeres de El Salvador (Association of Women of El Salvador).

AMES was initially founded on a directive by the Marxist-Leninist FPL (Fuerzas Populares de Liberación Farabundo MartÍ), one of the armed groups that made up the FMLN or Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front). AMES was perceived as part of a larger strategy to organize working-class women.

The group was thus made up not only of combatant women or FPL militants, but also of peasant civilians residing in FPL-controlled territories or in refugee camps in neighboring countries. Soon the group engaged not only in grassroots organizing, but also in educational work, and even international speaking engagements.

In the process, its members developed not only a revolutionary but also a distinctly feminist consciousness. In the guerilla territories, sexism was challenged, and gender relations altered under AMES’ influence. As Diana Carolina Sierra Becerra, a postdoctoral fellow for the Project “Putting History in Domestic Workers’ Hands,” a collaboration between Smith College and the National Domestic Workers Alliance, mentions:

“Scholars are correct to argue that participation in class-based movements does not inevitably lead to feminist consciousness or a change in gender hierarchies. While the FPL insistence on mass organizing benefited women, AMES organizers made deliberate choices to reframe FPL theories and practices, and Marxism more broadly, in order to confront the specific forms of oppression that impacted the lives of rural women.”

Since the ceasefire in the early ’90s, many of the former AMES militants have remained active and push forward a feminist agenda either within the FMLN, which turned into a political party, or in independent feminist groups. Once again, this essay is trying to pose a counterview to the more accepted version of the FMLN being a group that was sexist, class-reductionist, and overly focused on military struggle.

The remaining essays, ranging geographically from Cuba to the Southern Cone [which includes Chile, Paraguay, Argentina and Uruguay — ed.], similarly seek to correct the historical record by documenting remarkable flexibility by (usually Marxist-Leninist) vanguard parties when working with non-member activists from other sectors of the community.

They also show that indigenous people are not some illiterate mass that served as a tool to advance ideas supposedly foreign to them, but have repeatedly proven to emerge as historical actors on their own accord, even when seeking alliances with established political parties of the left.

Voices of Latin America

Voices of Latin America was put together by a UK-based independent publishing and research organization, known as Latin America Bureau (www.lab.org.uk, LAB from here on), whose goal is to provide news, information and analysis from the perspective of the region’s poor and marginalized communities, as well as social movements.

This collection was originally conceived as an update or replacement of an earlier LAB title “Faces of Latin America,” currently in its fourth edition. Since a significant part of LAB’s mission is to give “voice” to the less powerful of Latin America, the conclusion was to conduct interviews and give this marginalized sector room to “speak.”

The editor of the Voices of Latin America, Tom Gatehouse, who holds an MPhil in Latin American Studies from Cambridge and heads the LAB’s Voices Team, tells us who represents these voices:

“This is a book of many voices: of anthropologists and archaeologists; and politicians; women and LGBT people trying to halt gender-based oppression and violence; indigenous activists fighting oil drilling on their territory; residents of favelas resisting evictions; students staking their claim to a free, universal, and high quality education; and many more.”

The result is a veritable tour de force. Nine authors contributed the 11 chapters of the book, which are themed and based on over 70 interviews, spanning 14 countries. Almost all the interviews were conducted between 2016 and 2018, a crucial moment in Latin America’s recent history due to the retreat of the earlier pink tide that had swept across the region in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Those interviews that could not be considered for the written book format can be found at www.vola.org.uk together with additional multi-media material. It is a site well worth checking out. The themes themselves also cover a broad spectrum of topics, ranging from environmental issues to cultural resistance.

The first chapter is an introduction titled “Living life on their own terms.” It provides us with some background on the previous pink tide era and the challenges that the return of right-wing governments backed by traditional elites represent for the marginalized sector.

One of the interviewees, the Argentine sociologist Maristella Svampa, identifies four common features (while acknowledging the range of very distinct policies and discourse across the governments associated with the “pink tide”). These are shared across the spectrum — from the soft-left administration of Michele Bachelet in Chile (2006-10 and 2014-18) to more interventionist administrations like that of Hugo Chavez in Venezuela (1999-2013):

• Challenging the neoliberal projects of previous administrations

• Introducing more unorthodox economic policies

• Developing a series of social policies aimed at the most marginalized sectors of society (which implied not only a salary increase, but also an increase in consumption which in turn helped increase the legitimacy of the “pink tide” in front of more classical economists

• Creating strong regional blocs of an anti-imperialist nature (such as UNASUR).

The most impressive results in terms of redistribution were arguably achieved in Brazil under Lula and under Evo Morales in Bolivia, but across the board the region saw a significant reduction in extreme poverty, much greater access to higher education amongst low- and middle-income groups, and greater efforts to engage with indigenous communities.

The reasons for retreat vary, from regular political cycles to an over-reliance on extractivism (or in the case of Venezuela, on just a single commodity) to military and institutional coups, as was the case with the overthrow of Manuel Zelaya in Honduras in 2009, Fernando Lugo in Paraguay in 2012, Dilma Rousseff in Brazil in 2016, and most recently Evo Morales in Bolivia.

The remaining chapters look at a range of topics from state repression and urbanization (“State violence, policing, and paramilitaries,” “Spaces of everyday resistance: The right to the city”); a pushback from students, intellectuals, journalist and artists (“The student revolution,” “The New Journalism: Now the people make the news,” “Cultural Resistance”); to environmental and indigenous rights (“The hydroelectric threat to the Amazon basin,” “Mining and communities,” “Indigenous people and the rights of nature”).

The struggle against culturally engrained machismo, sexism and prejudice is highlighted in “Fighting Machismo: Women on the front line” and “LGBT rights: The Rainbow Tide.” The former piece was particularly interesting, since Latin American sees some of the highest gender-based violence and femicide rates in the world and also has to face draconian anti-abortion laws.

In addition to cultural machismo, another major factor contributing to gender-based violence has been the growth of organized crime. As the director of the Honduran women’s rights organization Las Hormigas (The Ants), Eva Sánchez, explains:

“Within organized crime, the body of a woman is used for taking revenge. It’s said that if you murder a woman it settles the account.”

Political upheaval is also identified as endangering the physical safety of women. In the aftermath of the Honduran coup of 2009, for example, the feminist struggle in general was criminalized, and women who participated in anti-coup demonstrations were subject to torture and rape.

Conclusion

Both titles have their merit and are contributing a unique perspective to any discussion centered around Latin American movements. Making the Revolution may hold more interest to Latin American scholars or history buffs, but rather than being stale, this book should be of importance to the left in general for a couple of reasons.

Firstly, as the editor Kevin A. Young correctly points out, “there is value in simply uncovering hidden histories of resistance to oppression.” He goes on to quote historian Jeffrey Gould:

“In a world in which the very idea of fundamental social change has become chimerical, where elementary forms of human solidarity seem utopian, past examples of solidarity, courage, and creativity should be excavated and remembered.”

I would agree with this notion; we live in a capitalist society and it is certainly not in the interest of the ruling elite to promote this kind of analysis. It is therefore upon us to record, learn and disseminate this alternative history.

Secondly, Young argues that these past struggles for emancipation hold valuable lessons, both inspiring and cautionary. I would add that there is nothing wrong with simply paying homage to historical social activists, so that they and their deeds remain present in our collective memories.

Voices of Latin America obviously took a very different approach. I think it is an extremely helpful tool for people who want to understand what is happening across the various social movements on the left in Latin America right now, and may even help as a guide for activists engaged in similar struggles in this country. It is also rather suitable as a reference book, if one were interested in just certain aspects of movements more than others.

I think where both Making the Revolution and Voices of Latin America fall a little short, however, is in providing suggestions on how to potentially combine all the different struggles. Neither one has an actual conclusion tying it all together. Making the Revolution only provides conclusions for each chapter, but nothing overarching. Voices of Latin America does not provide any.

I am mentioning this because, as socialists, we realize that all the struggles of the different social movements are systemic ones. You don’t have to scratch far beneath the surface to see that they all point to the same underlying mode of production. The common denominator is capitalism.

If we are serious about overcoming capitalism in an era where a vanguard party concept seems both obsolete and pretentious, we must find other ways to unite these struggles and take them out of their respective silos.

January-February 2020, ATC 204