Against the Current, No. 203, November/December 2019

-

Impeachment and Imperialism

— The Editors -

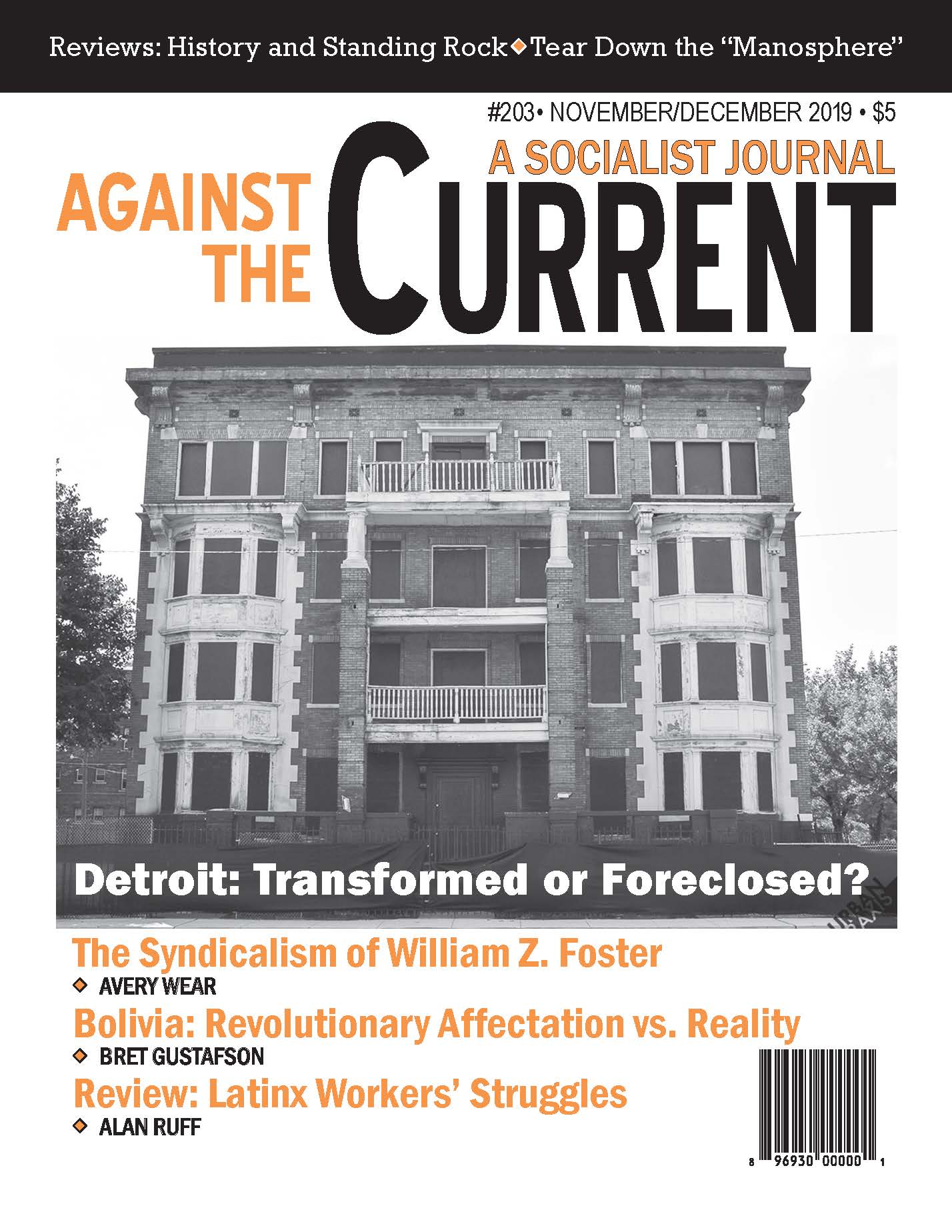

Detroit Foreclosed

— Dianne Feeley -

An Overview of Detroit's Affordable Housing

— Dianne Feeley -

Thoughts on Bolivia

— Bret Gustafson -

Viewpoint: Defeating Trump

— Dave Jette -

Which Green New Deal?

— Howie Hawkins -

Howie Hawkins' Statement on Presidential Run

— Howie Hawkins - Radical Labor History

-

Introduction: William Z. Foster and Syndicalism

— The ATC Editors -

William Z. Foster and Syndicalism

— Avery Wear - Reviews

-

Voices from the "Other '60s"

— David Grosser -

New Deal Writing and Its Pains

— Nathaniel Mills -

Latinx Struggles and Today's Left

— Allen Ruff -

Tear Down the Manosphere

— Giselle Gerolami -

Turkey's Authoritarian Roots

— Daniel Johnson -

Remembering a Fighter

— Joe Stapleton -

History & the Standing Rock Saga

— Brian Ward - In Memoriam

-

In Memoriam: Hisham H. Ahmed

— Suzi Weissman -

In Memoriam: William "Buzz" Alexander

— Alan Wald

David Grosser

You Say You Want a Revolution: SDS, PL, and Adventures in Building

a Worker-Student Alliance

John Levin and Earl Silbar, editors

San Francisco, 1741 Press, 404 pages, 2019, $18.95 paperback.

JACOBIN RECENTLY REVIEWED a couple of books about FBI infiltration and disruption of the left.(1) One reviewer wrote that the book Heavy Radicals contains a bombshell that upends our understanding of the disintegration of SDS. There were a number of FBI infiltrators at the fateful last SDS convention where the faction that went on to become the Weather Underground outvoted the Progressive Labor Party (PLP). Heavy Radicals shows that the FBI gave its infiltrators explicit instructions on how to vote — against the PLP.

The FBI’s reasoning was that they could handle the isolated adventurism of the group that would soon become the Weather Underground, but they feared the PLP could turn SDS into a disciplined, mass organization.

Historians and memoir writers in the 50 years since SDS cracked up have followed the FBI’s preference for Weatherman luridness. One could easily fill a bookshelf with histories of the group, histories of the ’60s that assign a primary role to the group and memoirs of ex-members.

You Say You Want a Revolution (YSWR) goes a little way to redress that historical imbalance, containing 23 chapter length remembrances of the other wing in SDS — the Worker Student Alliance Caucus and its leadership core — the Progressive Labor Party (PL).

PL/WSA has up till now garnered almost no attention except condemnation as the skunk at the new left garden party — receiving almost universal blame for the 1969 implosion of SDS, which was the most important white student radical organization of the time. WSA competed with the precursors of the vastly over-exposed Weather Underground and the forerunners of various “New Communist” groups of the ’70s for control of SDS leading to the ill-fated split that destroyed the organization in 1969.

Analysis of ’60s movements has often been divided on the questions of the “good” ’60s (the early SDS, participatory democracy, the beloved community of SNCC) and its displacement by the “bad” ’60s (violent protest; revolutionary Black Nationalism, collapse of the liberal Democratic Party coalition leading to the ascent of the Republicans).

Many writers lay much of the responsibility on PL for the transition to the bad ’60s. Kirkpatrick Sale, for example, in his pioneering history of SDS presents a parallel narrative of PL’s development and initiatives in SDS as if it were a body alien to the organization proper (set off by solid line divisions in the text). He doesn’t treat any other faction that way, implying that the organization’s destructive factionalism was entirely PL’s fault.

But even those who defend the “bad ’60s” as a healthy development, approving the displacement of reformist illusions by revolutionary consciousness, for the most part disdain PL. They see it as an anachronistic throwback to the old left dominated by the debates of the 1930s, which a new ’60s radicalism had passed by in search of up-to-date answers to current, not past, questions.

Now, in YSWR PL/WSA’ers tell their stories, and in many ways their experience parallels that of the ’60s new left as a whole.

Origins and Personal Accounts

Drawn from various parts of the country, and including both those who joined PL and those who never did, the 23 contributors write for the most part about their personal experiences and motivation. They do little theorizing or reflection on PL’s shifting ideological trajectory and the volume doesn’t have an academic feel.

Although as should be expected, given both the recent revival of organized socialism and the deepening crisis that engulfs us, most draw lessons from their experience for today, experience definitely predominates over analysis. Editor John Levin writes in the Introduction:

“These accounts are both optimistic, for those still inspired and bitter, from those now critical of their involvement. The stories they tell speak across the years, as a new generation of young activists … face[s] decisions about how to organize to stop wars abroad, confront racial oppression at home, and end violence and neoliberal exploitation.” (3)

Levin notes that in today’s rapidly expanding Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) some members find Marxism Leninism “trendy,” therefore “all the more reason to read the stories of activists who have been there before.”(3)

PL’s story began in 1962 with dissidents, favoring China in the emerging Sino-Soviet split, who left or were expelled from the U.S. Communist Party. In a period when SNCC, SDS and other emerging new left forces were still sorting out their positions regarding liberalism, the New Deal Democratic coalition and social democracy, PLers immediately distinguished themselves by their militant rhetoric and combative anti-imperialist and anti-racist politics.

In short order, the Progressive Labor Movement (which declared itself a party in 1965) took important initiatives sponsoring two student delegations to Cuba in defiance of the State Department travel ban, and leading an early march against the Vietnam War on May 2, 1964.

PLers’ defiant response to government persecution impressed many. Called before the House Un-American Activities Committee, which had been hounding radicals since the 1940s, members of PL’s Cuba trip defiantly disrupted the hearings. When Harlem erupted in 1965 after a white policeman killed a Black teenager, PL distributed a Flyer headed, “Wanted for Murder, Gilligan the Cop.” In response, New York State authorities indicted and convicted PL Vice Chairman Bill Epton on “Criminal Anarchy” and “Conspiracy” charges.

At a time when SDS still had an anti-communist exclusion clause in its constitution, and antiwar groups debated whether to allow communists to participate in their organizations, rather than avoiding or soft-pedaling their politics PLers proudly and defiantly embraced communism in public.

PL created an anti-imperialist student group, the “May 2nd Movement” in the wake of their 1964 march, then in 1966 disbanded it and sent their student members into SDS which seemed destined to become the center of radical white student organizing. Within SDS, PL organized a “Worker Student Alliance” (WSA) caucus to promote its strategy for student and antiwar organizing in SDS national and local chapter politics.

As a high school student in the late ’60s I was drawn to PL and organized with them at my school for two years. While I was peripheral to the action on college campuses that occupies most of the memoirs in the book, I was nonetheless part of the same political milieu. Three main political points attracted me to PL and I found these themes raised often by the YSWR contributors.

First, PL rejected the liberal explanations for the Vietnam war as a tragic mistake in an otherwise sound foreign policy born of over-zealous anti-communism of U.S. leaders, and for ongoing racism as the result of prejudice by individuals. Rather, they pointed to the systematic nature of the problems embedded in U.S. capitalism and asserted that no moral appeals to the good will of leaders could solve the problems.

Rather, only massive power directed against the ruling class could force leaders to change their policies. Ultimately only a socialist revolution could sweep away the evils that the movement confronted. In this PL’s views did not differ from those of many in SDS from varying perspectives, but the further strategic implications they drew most surely did.

Working-Class Centrality

PL staunchly asserted that students alone, or others (intellectuals, the “lumpen”) that were often put forward as a new revolutionary force at the time, could not overthrow capitalism — only the working class had that power.

In the wake of the shootings at Kent State in 1970, at the height of student campus unrest as student strikes proliferated on campuses across the country (more than 400, including my high school) some PL/WSA’ers dismissively advanced the slogan, “When students strike there is no school, when workers strike there is no war.”

So, it was of the utmost urgency for the student movement to find ways to ally with the working class which was itself seething with unrest at the time — exemplified by GI mutinies in Vietnam, revolts in big city Black ghettos and the biggest wildcat strike wave since 1946.

Bruce Clark, then a University of Iowa SDS’er, highlighted what for many was the fundamental appeal of PL’s analysis:

“(I)t was at [the] Bloomington [Indiana 1966 SDS National] conference that PL put forward the “Build a Base in the Working Class” proposal as a vision of moving forward in the student movement. I remember being hit by how obviously correct that argument was — that students were never going to make change on their own. I had an increasing appreciation that all the things I opposed clearly resulted from capitalism and that only the working class had the power to bring capitalism down.” (228)

But to carry out that massive revolutionary task we needed a revolutionary Marxist party like the Bolsheviks of 1917, or the Vietnamese and Chinese Communist Parties which we saw as leading the worldwide struggle against imperialism at the time. The U.S. capitalist class was well organized, ruthless and armed to the teeth.

We needed to be better organized and to create our own “general staff” to concentrate and direct our forces. The loose undisciplined activism of most student radicals was not sufficient: we needed disciplined and focused organization and we bought the exaggerated, and idealized, self-portrait presented by the party leadership.

Overthrowing the most powerful ruling class in history was easier said than done of course — then as now. The contributors to YSWR recount their efforts to carry out that daunting historic mission and the ultimate collapse of the project.

It is a story filled with excitement and elan, sustained for a time by extreme optimism and commitment. Many look back with pride to the priority they made in fighting racism. According to Joe Berry (University of Iowa, San Francisco State University):

“The concept was that this was something in the interests of most workers and therefore most people, not just a matter of moral solidarity….the value of emphasizing the link between the class interests and the need to oppose all forms of racism was a key contribution of PL/WSA.

“And finally, the idea that effective opposition to racism among working people was possible. Most white workers were not inevitable racists…. A united workers struggle against racism and against exploitation was possible.” (236)

WSA put forward what seemed like a reasonable strategic perspective as the ’60s crisis deepened. It challenged New Leftists to come to grips with the role of the Democrats in maintaining the system and to think about how to move beyond the welfare state capitalism that was starting to crack apart. And as a result, the caucus grew.

WSA led some important campus struggles — for example building support for the 1968 third world student strike against racism at San Francisco State College. Contributors to the book point with pride to the militance they displayed in the face of police repression, and their role in organizing white students to support Black students’ demands.

They also affirm the organizing skills they gained as they helped make the strike a mass struggle throughout the Bay Area. John Levin, at that time a PL leader at San Francisco State recounted:

(W)e reached out to the larger community for support. SDS …chapters on dozens of campuses on the West Coast…[sent] contingents of supporters…to SF State …and held rallies on their own campus to collect bail money and build support…. [W]e sent representatives from our speakers’ bureau to speak about the strike…. We addressed unions and community groups around the Bay Area…asking for resolutions of support….PL clubs [branches]… mobilized in support of the strike bringing their comrades from union caucuses and community groups to the picket lines and demonstrations. (116-117)

WSA had similar results in 1969 at Harvard when they led SDS in demanding the abolition of ROTC and an end to university expansion into the community, which was pushing up rents and driving out low income tenants. After activists took over the administration building, the administration brought in the police who brutally evicted the occupiers to the disgust and horror of the large numbers of students.

A campus-wide strike resulted, closing the university for the remainder of the semester. Harvard/Radcliffe SDS meetings ballooned to 400 members at least briefly.

Similar, although usually less spectacular, scenes played out across the country. SDS grew to perhaps 100,000 members (by no means solely due to the efforts of WSA). In the midst of widespread unrest in urban ghettos, broad disenchantment with the war in Vietnam and mounting repression, many concluded that revolution was a real and imminent possibility.

As PL/WSA’s strength grew within SDS, diverse forces came together to block them from winning control of the organization. In the overheated crisis-inflected atmosphere, the two factions split the organization at its 1969 convention, in effect killing it.

The ideological faction fighting meant a lot to a small proportion of the members, pro- and anti-PL, but little to the vast majority who simply moved on. PL had won control of SDS at the cost of destroying the organization in the process.

The Decline

For many in You Say You Want a Revolution, a turning point came around then. They mention a number of factors. Of course, the context became more difficult and maintaining optimism more difficult. After 1970 the seeming imminence of revolution faded for many across the left, not just those in PL. But a host of internal weaknesses caught up with PL/WSA as well and drove many former supporters and activists away.

PL began to break with some of its core political positions, often in undemocratic, top-down ways that blindsided activists on the ground. Formerly sympathetic to Black nationalism, the party leadership condemned all nationalism as reactionary including the nationalism of the oppressed embodied in the demands for Black Studies programs on campuses like San Francisco State and in the political program of the Black Panther Party (then under murderous attack by local police and the FBI).

They also condemned the Vietnamese for negotiating with the United States. The negotiations legitimated the U.S. war effort, PL said. And in 1971 they broke with China, charging that it had become capitalist.

To say the least, many of the contributors mention that defending such positions, especially condemning the Vietnamese National Liberation Front and the Panthers who had widespread sympathy and admiration from U.S. activists, was difficult. For many also, the way that these decisions were made exposed a deep-seated lack of internal democracy which was rotting away the organizations from the inside.

Eric Gordon in New Orleans noted that after the split, the PL-allied SDS remnant “had fallen into a deep authoritarian arrogance….[T}he National Office made all manner of highhanded decisions for the organization, hurling insults and accusations toward anyone who questioned their tactics or puffed-up leadership.” (98)

A couple of years earlier in the midst of the strike, John Levin, PL leader at San Francisco State, felt “gob smacked” when told by higher level party functionaries that the Party’s position of nationalism had changed and that he had to change a resolution that he had written for the SDS National Convention.

Returning home, “…PL retained its influence in the strike, mostly because of the respect people had for our leadership and militancy but also because we opportunistically explained PL’s position in such a way that allowed us to maintain our support for the strike demands.” (118-119)

Levin concludes that “I soldiered on as a PL member. It took me three wasted years to leave PL…”

Just as their reasons for joining the New Left were similar to those of non-PL activists, the contributors to YSWR experienced the same frustrations as the radicalism of the ’60s peaked and went into decline: the stability of the government, the effectiveness of repression, and their inability to widen their base beyond the student and post-student milieu.

The feverish activity that seemed appropriate in a seemingly pre-revolutionary situation was ultimately unsustainable over the long haul. And the party leadership increasingly resorted to manipulation and intimidation to keep the pace of commitment up and stifle the growing doubts of the rank and file.

Dead-end “Leninism”

The party’s version of Marxism became an obstacle to continued participation. PL looked to the CPUSA of its hyper-sectarian early 1930’s “Third Period” (before it had sunk, in their view, into “Browderite revisionism”) as its model of a revolutionary organization. The lessons they applied to PL’s political program and internal life copied the worst aspects of Stalinism and drove many of the YSWR contributors out of PL and WSA/SDS.

PL counterpoised “democratic centralism” (a central tenet of the construction of “Leninism” by the Stalinized CP’s) to “bourgeois democracy” and asserted the superiority of the former. Their version of democratic centralism was, as is the norm in Stalinist organizations, all centralism and little democracy: entirely top-down with their leadership making all important decisions and all leadership positions filled, in turn, by other members of the leadership as a self-perpetuating hierarchy.

In one of the most regretful reminiscences of the book, Emily Berg, who had been in the Boston area and later national student leadership of PL, reflects:

“PL was, by any useful definition, a cult, and the behavior of all of us who stayed with it past the earliest days, when it was weaker and less organized and thus more democratic, doesn’t bear close examination without discomfort. As in all cults, loyalty to the leadership was the highest virtue, and open disagreement with party positions was aid and comfort to the enemy. Almost any tactic, including lies and violence, became acceptable in the service of the party line. We are lucky that there was never the slightest chance of PL’s becoming an important force in the world.” (302)

PL’s version of “Leninism” asserted that that only one correct version of Marxism existed and that their party was uniquely situated to formulate it. Moreover, “revisionists” lurked everywhere set on derailing the movement with incorrect ideas and strategy. As a result PL related to the rest of the left with extreme sectarianism, thus its truly lamentable role in the destruction of SDS.

While many in the book assign equal blame to the anti-PL “Revolutionary Youth Movement” factions, nevertheless, as Michael Balter, who had been a UCLA SDSer, concluded:

“Where I really fault PL was that it did not see that it was being sectarian and did not realize that the way it was operating within SDS was diminishing the possibility of having a really broad-based organization. We were insisting on too much ideological purity. I don’t think anybody saw it that way at the time, but that was, in essence, what was going on. If you’re going to have Students for a Democratic Society as a broad based organization, PL would have had to have been able to tolerate more liberalism or just kind of run-of-the-mill radicalism, or even anticommunism.” (167)

Reflections and Lessons

Here lies the most important lesson that the PL experience has for the current mass radicalization especially within DSA. Many caucuses and factions are developing in DSA at the moment, and those of us who remember and rue the destruction of SDS should try especially to ensure that while strategic differences get an airing in the developing socialist movement, that it be done in a comradely manner that keeps the real enemy, corporate capitalism squarely in mind and seeks to preserve unity among all who are struggling for socialism.

Finally, PL adhered to an extremely narrow, workerist version of Marxism. Ironically, the ’60s was a period of great experimentation and creative ferment in the arts and politics. The horizons of Marxism expanded in many directions. Important previously unpublished works of Marx, like his 1844 Manuscripts and the Grundrisse became available and widely discussed in English for the first time, for example, but PL would have none of it.

Thus, PL Magazine in 1969 smeared noted left philosopher Herbert Marcuse through guilt by association, claiming that Marcuse’s work for the OSS (forerunner of the CIA) during World War II established that his views were part of the U.S. government’s intellectual counterinsurgency efforts. The article “Marcuse: Cop Out or Cop?” suggested that Marcuse’s search for an alternative to the working class as a revolutionary force was not just a different, even mistaken, view but a traitorous sellout.

Ernie Brill, YSWR contributor and one time culture editor of PL’s newspaper Challenge/Desafio spent “years…struggling with PL people to take a broader view of culture and literature and not be so dogmatic.”

The last straw came when he had a dispute with the paper’s editor over the movie version of Mel Brooks “The Producers.” The editor calls the movie “fascist.” Brill explains that it’s a satire. The editor responds: “‘It’s a fascist movie. The main dance number is “Springtime for Hitler” with all these dancing Nazis!’” Brill counters that his editor has misunderstood the comic intent.

The editor rejoins: “‘What is there to understand….I don’t think dancing Nazis is too hard to understand. They don’t need understanding comrade, they need killing.’” After more back and forth, the editor got someone else to write the review, Brill notes, and, “Before I went to sleep I typed up my resignation as Challenge Cultural Page editor and from Progressive Labor.” (142-143)

PL still exists, although it is no longer a force even within the narrow confines of the U.S. left. As the contributors to YSWR write from a vantage point long removed from participation in PL/WSA, their later life trajectories continue to present some common themes as does their summary of the PL/WSA experience.

First, again similar to ‘60s leftists of all types, they stayed on the left and continued living out their ideals in various ways. They sought employment and career choices in the “helping professions” broadly defined — teaching, social work, health care, the arts, progressive electoral politics, labor organizing, etc.

All have maintained some kind of political commitment around issues that motivated them in the ’60s, as well as others including feminism, LGBT liberation and environmentalism that only entered our consciousness in a mass way as a result of the political struggles of that era.

For them, the smug “yippie to yuppie” narrative, beloved by the mainstream media and based on the rightwing drift of select, media-created “leaders” like Rennie Davis, Jerry Rubin and Eldridge Cleaver.(2) and glibly portrayed in the popular movie “The Big Chill” (1983) is way wide of the mark. In this the PL/WSA’ers follow along with the general trend of ‘60s new leftists as a whole.(3)

However, almost none have continued participation in the organized, socialist left.(4) I find this surprising given two prominent themes of their ’60s radicalism that diverged from the general trend of the new left as a whole: the vital need for organization, and the centrality of the working class as an agent of social change.

Not that the organized left fared well among any surviving sector of the new left as the long neoliberal counterattack against the gains of the 1930s and ’60s ground on and on into the new century — so the disconnection of the former PL/WSA’ers need not surprise us much. In accounting for PL’s ills, the sectarianism, dogmatism and authoritarian internal structure, the contributors to YSWR most often lay the blame on “Leninism” or “democratic centralism,” which for them exhausts the possible positions on the revolutionary left.

PL had an answer — and called it communism. It was motivating and gave confidence and certainty for a while — until it no longer did. Then most of the contributors to YSWR were left still committed, but humbled and lacking the world view and encompassing plan of action that they once got from PL. Says Emily Berg of her current political beliefs.

I think I would classify myself as an anarcho-skeptic ….like most people after the disastrous and lethal failure of socialist revolutions…it’s not at all clear to me that there is any real workable alternative to “democratic socialism” which is really just managed capitalism….I don’t know what the “answer” is; I even suspect that there isn’t one; but I usually can know which side I’m on. It may be that that is all that can ever be done; in any case it’s the best I can do for now. (306)

Looking back, it seems to me that the dreams we had of revolution in the 1960s were unrealizable but we could have created some lasting left organization that would have better contested the one-sided class war we have faced since then. But for the majority of the YSWR authors, revolutionary socialism was a dead end with nothing to replace it.

Their view of Leninism — as practiced at the time in the USSR, China, the pro-Soviet Communist Parties and further left grouplets like PL — as expressing the essence of what revolutionary Marxism could be is to me ahistorical and circumscribed. Virtually none of the contributors analyzes their experience in terms of Stalinism.

They do not see the Marxism of PL and the many “New Communist Groups”(5) that followed quickly on the collapse the New Left in the 1970s as a stage in the unfolding history of the left that reached a turning point with the collapse of the Soviet Bloc in 1990 — one that opened up new possibilities for renewed socialist organizing at least in the long run.

But even at that time of SDS’s implosion, alternatives to Stalinism existed: the International Socialists (a forerunner of Solidarity), the New American Movement, the Socialist Workers Party and radical pacifist groups were all available alternatives although even taken together they didn’t have a comparable national profile or membership.

The collapse of the Soviet Bloc and the development of capitalism in China has presented an opportunity for a new, different form of Marxism, but the YSWR contributors for the most part see the era of organized Marxism as over or at least don’t feel qualified to speculate on or participate in building that new socialism (which the rapid growth of DSA suggests is currently happening).(6)

John Levin’s closing thoughts capture the spirit of cautious reticence of many of the contributors, “I’ve been out of the advice business for close to half a century, but I hope that the new revolutionary generation might draw some insight from the experiences detailed in my account and others in this book.”(120)

If in large part those experiences graphically demonstrate what not to do, they leave it up to a new generation to figure out a way forward.

Notes

- See “Half the Way with Mao Zedong” by Paul Heideman, Jacobin, May, 2018 and “Enemies of the Left,” by Chip Gibbons, Jacobin, March 2019.

back to text - On the media’s role in “selecting” and “certifying movement leaders see Todd Gitlin The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media in the Making and Unmaking of the New Left. University of California Press, Berkeley (1980).

back to text - See Richard Flacks and Jack Whalen, Beyond the Barricades: The ’60s Generation Grows Up (1989).

back to text - Becky Brenner (71) joined the October League (later CP ML) which collapsed in the early 1980s. Eric Gordon joined the U.S. Communist Party in 2009 “now that it had no Moscow line to ‘tail’” (102), and Ed Morman’s author bio lists him as a member of DSA “at least on paper.” (187)

back to text - On the New Communist Movement of the 1970s see Max Elbaum, Revolution in the Air (Verso 2018).

back to text - On the International Socialists Milton Fisk, “Socialism From Below in the United States” Chs. 5 & 6 http://www.marxists.de/trotism/fisk/ch5.htm; on NAM https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_American_Movement; on the SWP Breitman, George, Le Blanc, Paul, & Alan Wald, Trotskyism in the United States: Historical Essays & Reconsiderations, Humanities Press International, 1996; for radical pacifism Barbara Epstein, Political Protest and Cultural Revolution: Nonviolent Direct Action in the Seventies and Eighties, University of California Press 1991.

back to text

November-December 2019, ATC 203

A minor historical note on David Grosser’s review of “You Say You Want a Revolution.” The May 2 1964 antiwar demonstrations held in New York City, San Francisco, Boston and several other cities were initiated from an ecumenical “Socialism in America” conference held in March in New Haven sponsored by the Yale Socialist Union. The conference designated three coordinators for organizing the protests, Russell Stetler of SDS, Levi Laub of the Progressive Labor Movement and Peter Camejo of the Young Socialist Alliance. It was after the relatively successful May 2 protests that the Progressive Labor Movement created the May 2nd Movement under PL’s political control.

I remember Peter Camejo telling me about his experience with the May 2 protests. I referred to Fred Halstead’s history of the U.S. movement against the Vietnam War (Out Now! pp. 22-23) to corroborate my recollection and found additional information, some shared above.

I believe there is a minor error concerning Russell Stetler, in Dayne Goodwin’s comment. Stetler, the chairman of the May 2nd Committee, did not represent SDS. (As noted by Goodwin, Levi Laub [PL] and Peter Camejo [YSA] were named coordinators.)

for more, see Mary-Alice Waters, “Maoism in the U.S.: A Critical History of the Progressive Labor Party”, Chapter 6, “A Sorry Record on Vietnam” (1969). https://www.marxists.org/history/erol/1960-1970/waters-pl/chapter6.htm

Fred Halstead explains that: “The coordinators of the protest, which was to take place in several cities, were Russell Stetler, a Haverford College student who had recently joined SDS; Levi Laub of the Progressive Labor Movement (later Progressive Labor Party); and Peter Camejo of the Young Socialist Alliance.” (Out Now! p. 22)

Neither Halstead nor i said that Stetler “represented” SDS.

Mary-Alice Waters says: “A May 2 Committee was established, with Russell Stetler from Haverford College as chairman, and Peter Camejo (YSA) and Levi Laub (PL) as coordinators.”

Stetler may have been chairman and a coordinator. I don’t think Waters’ comment necessarily contradicts Halstead’s comment that Stetler was a coordinator.

Clearly an effort was being made to build a broad, united left protest. I made my comment to clarify that the May 2 protest was not simply a project of the Progressive Labor Movement.

Alan was able to find May 2 Committee letterhead which shows that Stetler was chairman; Camejo and Laub were the two coordinators.

The book shows the dangers of waiting fifty years to write a memoir. Having been an active member of the PLP for over 50 years and in a leadership role most of that time, i have a different memory of the period from the middle sixties to the early seventies. The party’s line was in constant flux during that period as we got a better understanding of the past errors of the communist movement. When the party broke with China after crushing of the Cultural Revoluiton, it was widely discussed. Some left the party over the quesion. Does anyone think China is still a beacon of a communist future? We could have done a better job on presenting our line on revisionism and nationalism but I do not think it was wrong. I have a stack of internal buttetins the party put out reflecting the discussion that went on. It is about 3 feet high. Overall the book concentrates too much on the party’s weaknesses rather than its strengths. I am sure the party could have done better, but the bottom line is the party was trying to build a communist movement in a period when the world communist movement was in decline. The concept of the worker-student alliance was developed and it persists today on many campuses and the idea of for fighting communism has been kept alive. You might think it is on life support, but I think it is better than that. I am not going to comment on many of the specifics in the book because my memory is no better than that of the contributor. Building a revolutionary party is essential to changing society and achieving a communist future. Building a party is hard and PL has certainly made many mistakes, but they have not given up. Unfortuately many of the contributors to this book have and that is sad.