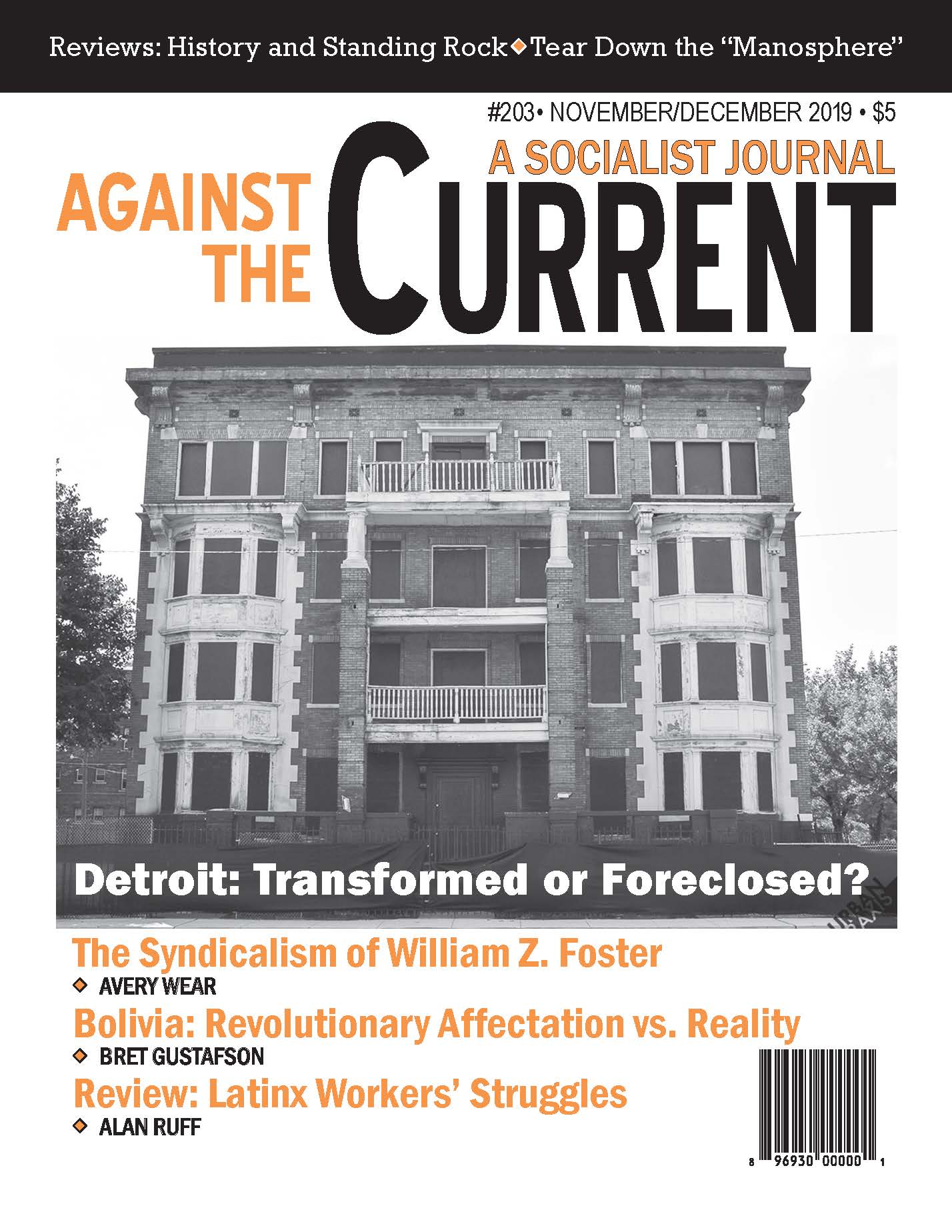

Against the Current, No. 203, November/December 2019

-

Impeachment and Imperialism

— The Editors -

Detroit Foreclosed

— Dianne Feeley -

An Overview of Detroit's Affordable Housing

— Dianne Feeley -

Thoughts on Bolivia

— Bret Gustafson -

Viewpoint: Defeating Trump

— Dave Jette -

Which Green New Deal?

— Howie Hawkins -

Howie Hawkins' Statement on Presidential Run

— Howie Hawkins - Radical Labor History

-

Introduction: William Z. Foster and Syndicalism

— The ATC Editors -

William Z. Foster and Syndicalism

— Avery Wear - Reviews

-

Voices from the "Other '60s"

— David Grosser -

New Deal Writing and Its Pains

— Nathaniel Mills -

Latinx Struggles and Today's Left

— Allen Ruff -

Tear Down the Manosphere

— Giselle Gerolami -

Turkey's Authoritarian Roots

— Daniel Johnson -

Remembering a Fighter

— Joe Stapleton -

History & the Standing Rock Saga

— Brian Ward - In Memoriam

-

In Memoriam: Hisham H. Ahmed

— Suzi Weissman -

In Memoriam: William "Buzz" Alexander

— Alan Wald

Giselle Gerolami

Misogyny:

The New Activism

By Gail Ukockis

Oxford University Press, 2019, 336 pages, $24.95 hardcover.

GAIL UKOCKIS IS a writer, social worker and instructor who taught Women’s Issues at Ohio Dominican University for 11 years. In the title of her book Misogyny: The New Activism, she consciously avoided the word “feminism.” While Ukockis considers herself a feminist, she invites those who are not feminists but reject misogyny to read her book.

Ukockis argues that we are seeing new forms of misogyny, or “hatred of women,” with the rise of social media, be it rape threats by trolls on the internet or revenge porn by men who feel rejected. These new forms of misogyny and the less extreme sexism add to those that have always confronted women in public, whether at work, in the street, or elsewhere: objectification, dehumanization and humiliation.

Thus, feminism as a tool for social justice is still relevant today, and although it doesn’t appear in the title, Ukockis does advance a feminist agenda.

Ukockis’s book is divided into 10 chapters. The first seven describe aspects of misogyny. The last three take up activist strategies. Ukockis limits her scope to the United States and looks at historical forms of misogyny as well as current ones.

Ukockis uses “intersectionality” to conceptualize current feminist politics. The term, popular now, was first used in the 1970s by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, who looked at how identities could intersect and amplify discrimination.

Ukockis emphasizes that trauma, specifically Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE), is an often-overlooked aspect of intersectionality. African-American women face the “Angry Black Woman” stereotype and are threatened by police almost as much as are African-America males.

Native women are murdered at ten times the national average, and 84% of Native women experience some form of violence in their lifetime. Latina farm workers experience wage theft and health issues related to pesticide use, while Central American women risking the trek to the United States experience high levels of sexual assault along the way.

Using this theoretical perspective, Ukockis outlines some common forms of misogyny in U.S. society. In her section on gender violence, she includes her own research on sex tourism, which she conducted by studying public sex tourist blogs. She concludes that the growth of sex trafficking in the internet age was sparked by men who reject both U.S. dating sites and domestic sex workers because these women resist objectification in various ways.

Instead, these men want the ultimate “girlfriend experience” with underage women who pretend to love them. Unsurprisingly, sex tourist blogs are rife with misogyny, including ageism, fat-shaming and the ranking of women from one to ten.

Resisting Toxic Masculinity

Ukockis goes on to critique other online men’s spaces, or the “manosphere,” where life is a competition to become an alpha and get “hot babes.” The way to a “hot babe” includes negging (a negative comment designed to bring down a woman’s self-esteem) and kino, which is light touching to test the sexual waters without coming across as creepy.

Once a man has won a woman over, he is expected to physically and sexually dominate her. Men who are unsuccessful in the manosphere may become incels, involuntary celibates, who promote violence against women as punishment for having rejected them.

This behavior falls into the category of toxic masculinity, or “behaviors and attitudes of hypermasculinity that stress virility over cooperation and violence over compassion.” Ukockis points out that self-reliance, playboy behavior and power over women are linked not only to violence against women but to negative mental health in men. She believes that male self-compassion would go a long way towards lessening toxic masculinity.

Turning to reproductive health, Ukockis notes men’s ignorance about women’s bodies and their disgust at menstruation. At a time when male legislators show a profound lack of understanding of reproductive science, there has been promising activism against taxes on tampons and pads and for free feminine products in schools, prisons and homeless shelters.

Similarly, while abortion rights are under attack as never before, women are fighting back and talking openly about their abortions. Even with a majority of the U.S. population supporting abortion rights, doctors who perform abortion continue to receive death threats. Catholic hospitals not only deny abortions but refuse gender transition procedures, sterilization, or emergency contraception.

Some politicians, including Trump, think women should be punished for having abortions. Such criminalization of abortion will disproportionately affect marginalized women, since rich women will always be able to obtain abortions.

Ukockis calls for “thoughtful activism” and looks for examples where women have forged alliances with other movements, such as the labor and environmental movements.

Recently, UNITE HERE organized around panic buttons in hotel rooms to protect female cleaning staff who find themselves in unsafe situations with clients. Restaurant Opportunities Centers (ROC) United organized around low wages and the sexual harassment that 90% of restaurant workers experience.

Ecofeminism is another alliance. The women involved in resisting the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) fought against tremendous odds and “were injured by water cannons, concussion grenades, rubber bullets, tear gas, mace, sound cannons, and unknown chemical agents.

“They have been sexually assaulted on the front line; kept naked in their jail cells and denied legal representation; locked in dog kennels; permanently blinded.” (242)

Ukockis finds inspiration in the example of Lakota elder Spotted Eagle, who talks about bio-politics in opposition to corporate greed as “human life processes [that] are managed under regimes of authority over knowledge, power and ‘subjectivation.’ In other words, our indigenous bodies, which are essentially a direct reflection of Mother Earth, have been and continue to be controlled by corporations and governments that operate for profit without regard for human life.” (244)

Optimistic Outlook

Ukockis is optimistic about today’s resurgent feminism. The movement represents a cultural and political shift, with new opportunities for legislation on women’s issues.

One success was the Ending Forced Arbitration of Sexual Harassment Act of 2017. Forced arbitration had made it difficult for women to come forward about workplace sexual harassment.

The number of women looking to run for office has skyrocketed to 30,000 from 920 in 2015-2016. This number includes many African-American women. Young feminists have become energized and active in such movements as “Know Your IX” around Title IX.

If you removed the footnotes and illustrations from Misogyny: The New Activism, the book is quite short. The breadth of the topic is too ambitious for a book of this length. Ukockis jumps from one idea to the next without transition and without sufficient development.

Throughout the book are boxes and case studies. These disrupt the flow and contribute to the scattered effect. She meticulously footnotes her references and citations but fails to connect those references.

Critiques of capitalism pop up in passing throughout the book, but as a socialist feminist I found them lacking in depth. At one point, she lumps misogyny and “Marxism-Leninism” together as “stupid ideas that deserve to die out.” I am not one to defend Stalinism, but I found this less than helpful, and I suspect she might include all Marxists in the “stupid” category.

Her attempts at humor sometimes fall flat as she inadvertently plays into stereotypes; in her preface, she jokes about how she has become a “Scary Feminist” who carries scissors in her purse to castrate men.

The chapter on intersectionality compares the hierarchy of oppressions to the group of people she has encountered in the hot tub, each one trying to one-up the other on the numbers of surgeries they have had. This oversimplifies a complicated issue in a way that is not very instructive.

There are several other instances in the book where complex issues are reduced in ways that do nothing to advance the cause of women’s rights.

Ukockis shares that, as an instructor, she often had to develop her own materials when none existed. Her book serves best as a primer on women’s issues. The invitation for all to read the book as opposed to just feminists is appropriate, and her accessibility is admirable.

The opening chapters all end with “Action Steps,” and the last three chapters are a call to activism. How many books call on their readers so directly to get off the couch and do something? One might quibble about the specific content of her activist advice, but Ukockis’ call to action is both refreshing and necessary in the current political climate.

November-December 2019, ATC 203