Against the Current, No. 203, November/December 2019

-

Impeachment and Imperialism

— The Editors -

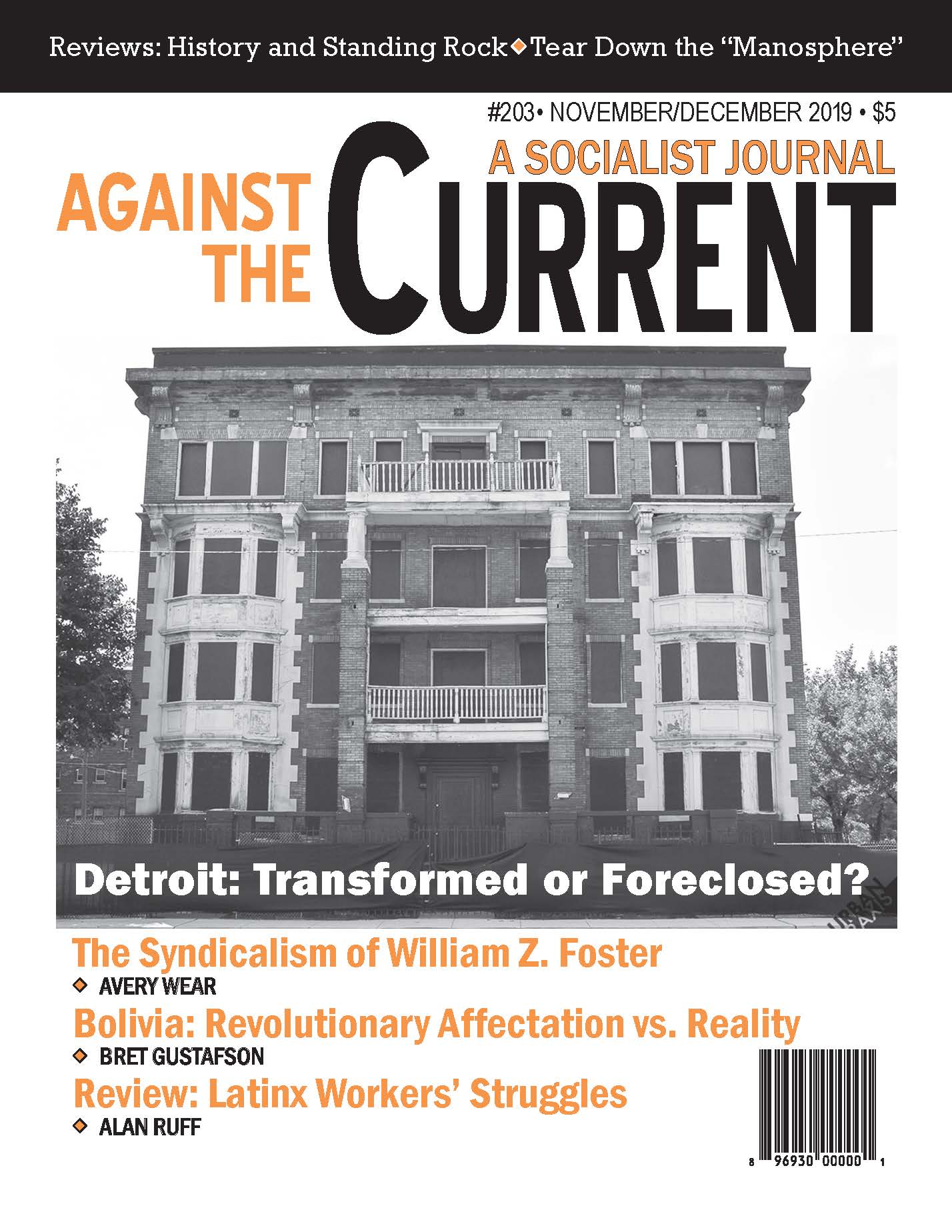

Detroit Foreclosed

— Dianne Feeley -

An Overview of Detroit's Affordable Housing

— Dianne Feeley -

Thoughts on Bolivia

— Bret Gustafson -

Viewpoint: Defeating Trump

— Dave Jette -

Which Green New Deal?

— Howie Hawkins -

Howie Hawkins' Statement on Presidential Run

— Howie Hawkins - Radical Labor History

-

Introduction: William Z. Foster and Syndicalism

— The ATC Editors -

William Z. Foster and Syndicalism

— Avery Wear - Reviews

-

Voices from the "Other '60s"

— David Grosser -

New Deal Writing and Its Pains

— Nathaniel Mills -

Latinx Struggles and Today's Left

— Allen Ruff -

Tear Down the Manosphere

— Giselle Gerolami -

Turkey's Authoritarian Roots

— Daniel Johnson -

Remembering a Fighter

— Joe Stapleton -

History & the Standing Rock Saga

— Brian Ward - In Memoriam

-

In Memoriam: Hisham H. Ahmed

— Suzi Weissman -

In Memoriam: William "Buzz" Alexander

— Alan Wald

Dianne Feeley

BETWEEN 1837, WHEN the first Michigan constitution abolished slavery, and 1910, with the Great Migration of southern Blacks — and southern whites — to the North, Detroit had no formal housing segregation. However, racial and class distinctions meant that the majority of Blacks lived in the older, more rundown lower east side.

In Michigan, Black men only won the vote with passage of the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. And although public schools were open to Black children, the fact that Blacks were clustered into poorer neighborhoods — although ethnically diverse — meant their schools had few resources and likely to be segregated.

It was only in the 20th century that housing segregation became enforced by custom, law and government programs. These ranged from restrictive contracts, which forbade selling property to anyone who was not white, to redlining for the purpose of receiving federal-backed mortgages to segregated public housing.

Detroit never had much public housing because city officials debated which “race” would the project house. However Brewster Housing, opened in 1938 under New Deal financing, was the country’s first public housing built for African Americans.

Brewster’s 701 low-rise apartments were located just north of the city’s business district, close to where the majority of Blacks lived and worked — Black Bottom and Paradise Valley. This housing project was paired with construction of Parkside Homes, 785 low-rise units on the far eastside and only open to whites.

Even before World War II was declared, the housing commission identified 70,000 substandard units in the city. At least a quarter million people flocked to find jobs in Detroit’s industries during the war. Three-fifths were African Americans, confined to the most rundown housing but forced to pay the highest rents.

Civil rights leaders convinced the housing commission to construct a Black public housing project, the Sojourner Truth Homes, in an industrial area near a white neighborhood. In early 1943, as Black families began to move in, white neighbors rioted. As a result, nearly 100 Blacks were arrested and three dozen hospitalized.

The housing commission then formally adopted a policy of segregated housing. They only began to disregard “race” in assigning families to specific sites a dozen years later.

After the war public housing was built for returning white veterans and their families in three additional areas on the city’s east and west sides. To ease the housing problem for African Americans, the housing commission built the Frederick Douglass Homes just south of Brewster, and the Edward Jeffries Homes a mile to the west.

These “elevator buildings,”as June Manning Thomas dubbed them, were not helpful in checking on children playing outside or monitoring visitors. As the government set income limits that forced out families with good jobs and skimped on maintenance, they became concentrations of poverty. Most have been torn down.

The purpose of post-war urban redevelopment was to halt the economic decline of the downtown business district, not to build affordable housing — even for those forced to move.By 1962 urban renewal had adversely effected one-third of the city’s African Americans.

Of the 3340 units of public housing that still remain in Detroit, there is a 95% occupancy rate and a waiting list of 5760.

Today public housing is primarily a voucher program known as Section 8. But once approved, the applicant must find a landlord willing to accept it. Detroit’s waiting list of 6000 has been closed for more than five years.

Currently, the federal government’s commitment to affordable housing is through tax credits given to developers. They then set aside a certain proportion of low-housing units, usually 20-40%, in the building. After 15 years, however, the owner can apply to convert these units to market rentals.

According to University of Michigan researchers, 7000 Detroit apartments and homes will reach the 15-year mark between 2016 and 2022. Since many are in the city’s more desirable areas, chances are that most will be lost to affordable housing.

Twenty years ago several non-profits built single family homes for low-income families. These were not well built nor did management companies maintain them adequately. Further, residents were told a portion of the rent would go toward buying the home but that never happened.

A 2016 city housing study found nearly 60% of Detroiters “rent burdened,” meaning they were paying more than 30% of their income for housing. Over the last decade, the average monthly rent increased by 30%, while median wages fell 20% when adjusted for inflation. As a result, Detroit averages about 30,000 rental eviction cases each year.

The U-M researchers project that the city needs at least 21,000 rentals earmarked for those making less than $20,000 a year. Meanwhile the city’s goal is to build 2000 new homes and preserve another 10,000.

November-December 2019, ATC 203