Against the Current, No. 202, September/October 2019

-

Hope Is in the Streets

— The Editors -

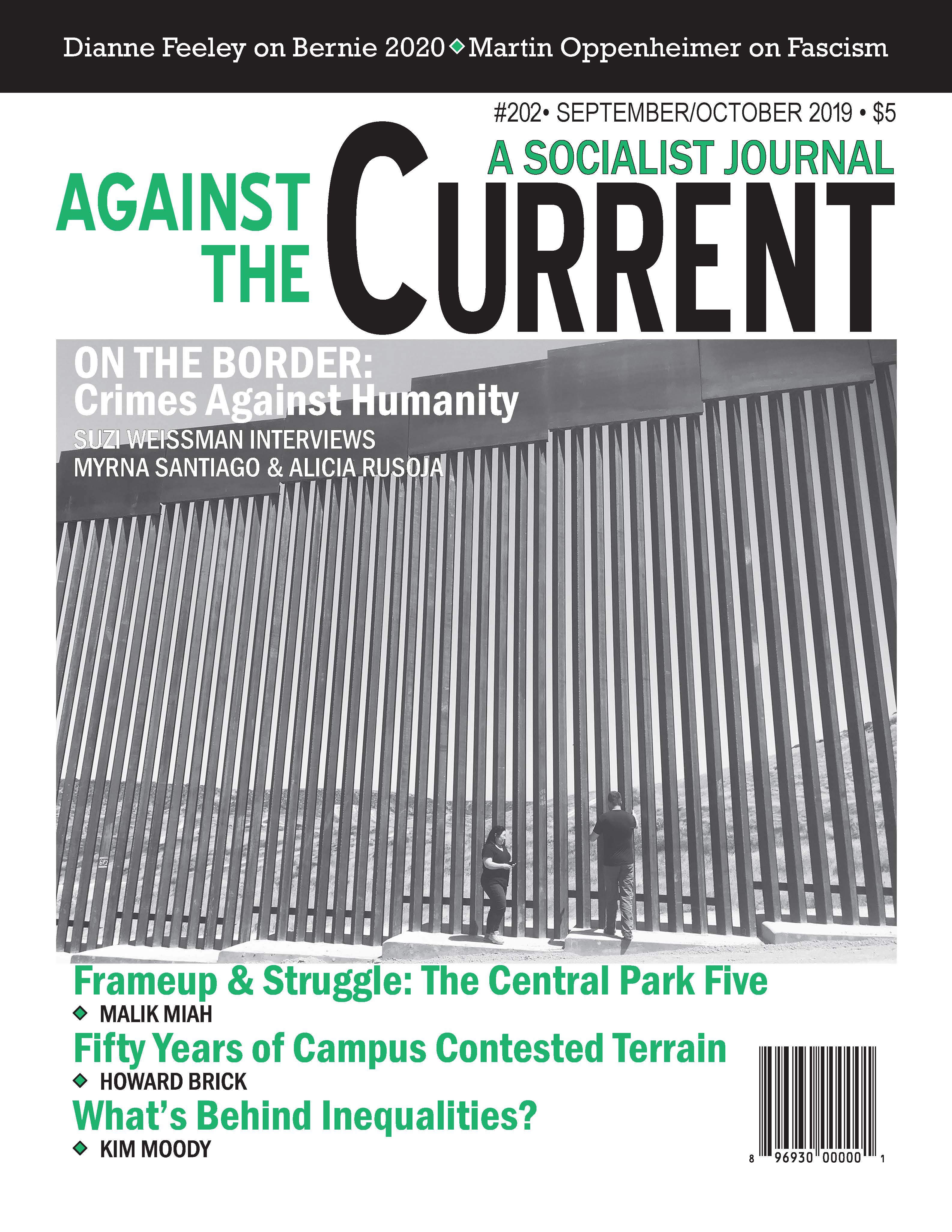

Talking to Those on the Border

— Suzi Weissman interviews Myrna Santiago & Alicia Rusoja -

What the Sanders' Campaign Opens

— Dianne Feeley -

Making the Master Race Great Again

— Steven Carr -

The Central Park Five Frameup

— Malik Miah -

Algerian Feminists Organize

— Margaux Wartelle interviews Wissem Zizi -

Palestine: Imperative for Action

— Bill V. Mullen -

The Crisis of British Politics

— Suzi Weissman interviews Daniel Finn - Siwatu Salama-Ra Conviction Overturned

-

Contested Terrains on Campus

— Howard Brick - Reviews

-

Competition, Inequality & Class Struggle

— Kim Moody -

Learning Through Struggle

— Marian Swerdlow -

What Is Working-Class Literature?

— Matthew Beeber -

A Debate That Never Ends

— Steve Downs -

Fascism--What Is It Anyway?

— Martin Oppenheimer -

Bolivia's Legacy of Resistance

— Marc Becker -

China: From Peasants to Workers

— Promise Li - In Memoriam

-

In Memoriam: James Cockcroft, 1935-2019

— Patrick M. Quinn

Martin Oppenheimer

The Coming of the American Behemoth

The Origins of Fascism in the United States, 1920-1940

By Michael Joseph Roberto

Monthly Review Press, 2018, 413 pages plus 33 pages of notes, $20 paperback.

THE HEADING OF Michael Joseph Roberto’s first chapter, “Fascism as the Dictatorship of Capital” summarizes the book’s central thesis: This Capitalist dictatorship will purportedly end the chaos of laissez-faire capitalism through a complete synchronization of state and private institutions (Gleichschaltung in the German). Today “the fascist reordering of government is underway under Trump…as a bona fide American fascist.” (407-8, 410)

This approach to understanding fascism is not new. It has been debated within the left since the early 1930s. Roberto, a Greensboro, N.C. activist and retired academic historian, intends in this book to convince us of its continued viability.

He begins by surveying the history of American industry, its growing role in the world, and how with the First World War U.S. finance capital became the world’s banker. He describes how “technological innovation on a massive scale raised the productive capacity of American industry to historic levels which, in turn, made the United States the world’s first, true consumer society.” (43)

The advertising industry became increasingly important, not only in promoting consumerism but also in propagandizing for a culture of individualism and opposition to collectivism in all its forms. Presidents Harding, Coolidge and Hoover, all Republicans, enacted tax cuts and tariffs and cut the size of the federal government, each one appointing industry and banking leaders to cabinet posts.

Under Harding “the United States embarked on an imperialist agenda facilitated by able capitalist modernizers in his cabinet who understood” that prosperity meant access to foreign markets and natural resources abroad. (151) Military interventions logically followed.

The rapid growth of the economy in this decade led to “a spectacle of prosperity.” (79) Roberto walks us through a set of writers promoting a range of schemes that promised endless prosperity and an end to class antagonisms.

Thomas Nixon Carver blathered on about wiping out the distinction between laborers and capitalists. Norman Fay of Remington Typewriters and V.P. of the National Association of Manufacturers advocated that businessmen (sic) enter “public service,” since the average man is incapable of governing. Put more business in government and more government in business, he thought.

Edward Bernays, the “father” of public relations, believed that he and other molders of public opinion would do a better job. Why Roberto spends so much energy on what he himself terms this “ballyhoo” about capitalist progress (112) is not clear. These writers were certainly elitist, but their connection to fascism is tenuous. In any event, this ballyhoo would be laid to rest in 1929.

Struggle, Repression and Crisis

A massive wave of strikes in 1919 triggered by inflation and increasing post-war unemployment had been largely defeated. The big steel strike led by future Communist William Z. Foster, then a Wobbly, was suppressed in part due to the red scare that followed the Bolshevik revolution.

This hysteria led to the infamous Palmer Raids in January, 1920, targeting immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe. In 1924 the National Origins Act drastically limited immigration from those and other non-Northern European areas. By then “Anxiety and fear over changing economic conditions [had] gripped much of rural society…Nativism defined the political landscape throughout small-town and rural existence” creating the conditions for the revival of the KKK. (37) “It is within all of these developments that we find the genesis of fascist processes….” (53)

Meanwhile, the real deal in the form of Mussolini’s Fasci had seized power in 1922. Italy’s economy lagged behind such core economies as Great Britain and Germany, and its weak and divided ruling class greeted the new order with enthusiasm. U.S. business leaders as well as the three Republican presidents of the decade “jumped on board, as did many of the leading newspapers like The New York Times….” (156)(1)

Within a few years the Wall Street crash would trigger the Great Depression and open the road to fascist power in Germany. The Communist Left in the United States was not alone in fearing similar developments here.

Communist writers A.B. Magil and “Henry Stevens” in The Perils of Fascism (1938) wrote that “The germ of Fascism was inherent within American monopoly capitalism but it was not until the economic crisis…that it developed into a definite political force of ominous proportions.” (54)(2)

As the “fountainhead” of American fascism, they argued, “Big Business” would encourage the concentration of power in the executive and the diminution of power in legislative bodies. R. Palme Dutt, a Communist from India, saw the Roosevelt regime and its tepid Keynesianism as “pre-fascist” in 1934. (Ayçoberry, 55)(3)

Alexander Bittelman, a CP-USA leader, wrote in August 1934 that the New Deal, “hailed by the Socialist Party as a ‘step to socialism’ and by the A.F. of L. bureaucracy as a ‘genuine partnership of labor and capital’ is a weapon for a more rapid fascization of the rule of the U.S. bourgeoisie…”(4)

Even Lewis Corey (Louis Fraina), a prominent Marxist theorist who had by then broken with the CP, thought that Roosevelt’s National Recovery Administration was proto-fascist.(5)

Nor was this idea limited to the Left. The growth of executive power in the Roosevelt administration led some right-wingers like George Sokolsky, a propagandist for the National Association of Manufacturers, to think the New Deal would lead to fascist dictatorship.

The idea of Roosevelt as a proto-fascist was not a complete fantasy. The highly respected journalist Walter Lippman apparently advised Roosevelt a month before his inauguration that there might be “no alternative but to assume dictatorial powers” given the crisis. Roosevelt pretty much threatened Congress that if it didn’t act promptly on his legislative proposals he would ask for “broad executive power” to deal with the emergency. (218-219)

In early 1937 Roosevelt, confident that his policies had succeeded, reined in deficit spending with the result that the economy dived back into a recession. “Big Business smelled Roosevelt’s blood” and, according to historian Kenneth Davis, hired gangs of “private armies” to attack unions. Said Davis, “…the threat, of a Fascist coup appeared to Roosevelt not only real but growing…” (Quoted, 332, 333).

Roosevelt, Roberto tells us, “was surrounded by individuals who had clearly and forcefully identified Big Business as the main fascist threat in America.” (342) This faction urged the President to end the Depression through deficit spending. But there were also powerful deficit hawks who advocated a balanced budget, hardly a fascist approach.

For his own reasons Roosevelt finally aligned with the former group and in April, 1938 sent Congress a budget requesting billions for relief, public works and other stimulus programs.

How the System Endures

Neither the Nazi nor the New Deal regimes prefigured the collapse of the economic order predicted by some Communists. American capitalists, according to Roberto, “forged new means to keep a Pax Americana intact, the social-democratic welfare state.” (181) Never mind that New Deal legislation was adamantly opposed by most sectors of capital and that the adoption of a weak proto-Keynesianism (hardly social-democratic) came only after intense battles within the administration.(6)

The New Deal was not simply a construct of “the ruling class.” It was the outcome of fierce battles among different sectors of the ruling class. It was also a response to large-scale unrest and a growing militancy by parts of organized labor.

The German Communist Party had believed that the capitalist order was on the verge of collapse in 1933 and that Fascism represented a last desperate attempt to save it, but would soon fail. The Social Democrats were labelled “social fascists,” and the Communist Party was to wean its proletarian membership away in a “united front from below” in anticipation of that collapse. “After Hitler, us” as the saying went.

With the stabilization of the Nazi regime, however, a new policy was required and the strategy of the “popular front” replaced the “united front from below.” In August 1935, Communist Georgi Dimitroff delivered his famous report to the Seventh World Congress of the Communist International in which he held that fascism was “the open and terroristic dictatorship of the most reactionary, most chauvinistic and most imperialist elements of finance capital.”

Note that Dimitroff’s definition differed from the proposition that fascism is engendered by “Big Business” as a whole. Rather than representing a more sophisticated analysis of German ruling circles, however, the theoretical shift actually represented a change in Stalin’s strategy vis-à-vis the Hitler regime. “If only open and terroristic dictatorship was fascist, then the bourgeois democracies were not — or no longer! — fascist” (Aycoberry, 53).

Only a fraction of big business was responsible for fascism, and so the popular front against fascism should reach out to include the middle and even parts of the capitalist class. The implication was clear: popular front meant that revolution against the entire capitalist system was off the table. Efforts at revolutionary transformations (as during the Spanish Civil War) would be suppressed by force if necessary.

Roberto, in his ninth chapter, walks us through what journalist George Seldes called “small-fry fascisti” who diverted attention from the real source of fascism: Big Business. (254) Nevertheless, Roberto considers some bigger small-fry who might become “shock troops for reactionary capitalists” to be important. (256)

There was William Dudley Pelley, an anti-Soviet and anti-Semitic journalist who founded the Silver Shirts on Jan. 30, 1933, the day Hitler was appointed German Chancellor. A year later Pelley had 15,000 all-white members dedicated to a corporatist economic structure that would in theory abolish classes.

Then there were the Khaki Shirts, headed by a “General” Art J. Smith, who called for veterans to march on Washington on Columbus Day, 1933. It fizzled and Smith went to prison for perjury.(7) The Black Legion was a spinoff of the Klan revival of the 1920s and was able to recruit thousands into “regiments” throughout the Middle West in 1934 and 1935.

Oddly, Roberto overlooks the brown-shirted pro-Nazi German-American Bund, active in several Northeastern States. On Feb. 20, 1939, the Bund held a rally at Madison Square Garden with some 20,000 in attendance, many in full Nazi regalia (while an anti-fascist mobilization fought the police outside). When the war began in Europe, its Nazi sympathies led to the Bund’s collapse.

The Fascist Threat, Rise and Fall

The Catholic Father Charles Coughlin, in suburban Detroit, was more significant by far than these “shirt” groups. “Coughlin commanded a great following across much of America through his brilliant use of the radio…(he) successfully tapped into the anxiety and fears of the middle and lower middle classes by explaining how they had been victimized by Big Business and the federal government,” both controlled by international Jewish bankers. (269-70)

His populist message eventually reached an estimated 40 million in 23 states. Roberto catches the fascist flavor of Coughlin’s thinking: “The organic unity of the corporate state is far superior to an atomized liberal democracy.” (279) Coughlin’s following had petered out by the time the U.S. entered the Second World War.

Huey P. Long was another story, elected Governor of Louisiana in 1928 as a populist, and to the U.S. Senate in 1932. Like Mussolini, Long was said to be a modernizer. In the process of turning Louisiana into his personal fiefdom, the story was that he brought its oligarchy to heal, built infrastructure and expanded educational opportunities, even as he secretly took payoffs from elements of the corporate sector, especially Standard Oil.

However, this relatively rosy picture has been disputed. The journalist Carleton Beals, in The Story of Huey P. Long (1935), claimed that Long did nothing to raise the standards of living, especially for African Americans, whom he despised. Beals described Louisiana as a “monopoly capitalist and feudal enterprise…Culturally and economically, Louisiana is closer to Peru than to Wisconsin…” (285)

Nevertheless, Long’s populist rhetoric, his platform of redistribution of wealth and his “Share the Wealth Clubs” attracted such large followings that even President Roosevelt expressed alarm. If his life had not been cut short by an assassin on September 10, 1935, could Long have succeeded in ousting Roosevelt to become a genuine fascist ruler clothed in Americanism? Sinclair Lewis’ novel It Can’t Happen Here (1935) suggested he could.

The reality of fascism in Europe and the threat of it in the United States poses the question of whom its supporters were. There is widespread agreement that “middle class” or “lower middle class” elements were heavily represented in proto-fascist circles in the 1930s and were the voting base for the Nazis, although the wealthy supported them disproportionally. They are similarly prominent in the U.S. ultra-right today.

The meaning of “middle class” is controversial to say the least. Most of the writers considered by Roberto seem to mean small-scale entrepreneurs, plus the growing sector of lower-level white collar workers.

A case study of the 1920s KKK in Athens, Georgia, found for example that the “single most common occupation of the Klan…was owner or manager of a small business or a small family farmer…White-collar employees of the so-called new middle class—salesmen, clerks, agents, and public employees — filled out the rest…” (147)

Mauritz Hallgren, a Nation writer, cited independent retailers in particular as hard-hit by the Depression and by the growth of chain stores and mail-order houses like Sears. The insecure position of these petty-bourgeois made them vulnerable to a politics of anger and scapegoating and attracted them to Coughlin, Long and the like.

Indeed, as Lewis Corey wrote, “the struggle to save such property as still survives from the all-consuming maw of monopoly capitalism drives the class to reaction…” (304) Recent U.S. studies, including those of “Tea Party” adherents, show similar tendencies.(8)

Although fascism might be the last stand of the petty-bourgeoisie for capitalism, this is not necessarily so for the white collar proletariat. In numerous studies of European elections before and after World War II, white collar workers supported parties of the moderate Left.(9)

Where Capital Places its Bets

Was fascism simply “bought and paid for” by financial and industrial interests, as Robert A. Brady, a favorite of Roberto’s, thought? (364) In the founding years of the Nazi Party funds came only from marginal groups of capital, “lone wolves,” as Konrad Heiden, a close observer of Hitler’s rise, called them.(10)

Hitler’s access to bigger funding came only when he was in coalition with more moderate groups. The Big Bourgeoisie had its own parties. As David Abraham, in his exhaustive study of Germany’s divided ruling class put it, “conflicts within and between the dominant social classes…rendered impossible a consistent and coherent set of policies capable of satisfying all the fractions…”(11)

Rather than fascism being a logical expression of capitalist domination, fascism was a last desperate attempt by the dominant segments of that class to find a way out of economic and political chaos.

Hitler’s “Brown [shirted — MO] Bolsheviks” were feared by the “respectable” German bourgeoisie. But “As (national socialism) grew and seemed likely to gain power, expediency dictated contributions as a matter of self-protection, even from people of wealth not otherwise sympathetic to the ‘socialism,’ national or otherwise, of a ‘workers’ party.”(12)

In fascist regimes capital remains in “full command of all the military, police, legal and propaganda power of the state,” Brady wrote.(13) But once in power, Hitler was never simply the instrument of German capital, acting on its orders. The factory is yours, said one observer, but the state tells you what to make, in what quantity and quality, and it provides raw materials and handles the markets. “All capital is at the immediate disposal of the government.”(14)

Hitler’s policy changed depending on what seemed opportune at the moment to extend his power. After 1938, with the country on a war footing, the Nazi Party was fully in command. But the Party and the State that it ruled, research has shown, were “characterized by…a highly disordered proliferation of agencies and hierarchies”(15) so that squabbles over turf were constant.

As for the U.S. “Corporate Community,” as Domhoff calls it, we have seen how divided it was during the Depression. Later, its dominant sector did not support Senator Joe McCarthy’s anti-Communist hysteria, or Governor George Wallace’s Presidential bids, both men considered proto-fascist by many on the Left.

A number of “power structure” studies have clearly demonstrated that the “Corporate Community” is not monolithic. There continue to be many disputes, including between a low-tax, low-regulation fraction and a more Keynesian wing that supports many social reforms and regulations.(16) These differences are also reflected in foreign policy, with the latter group committed to the United Nations and other international bodies.

Blurring Important Distinctions

Roberto’s conceptualization of fascism as the fusion between state and big business blurs the distinctions between fascism and other oligarchic states where capital also dominates. It does not differentiate reactionary dictatorships seeking to protect or restore an unregulated capital linked to the Catholic Church (e.g. Somoza, Pinochet) from post-feudal modernizing capitalism.

Under Roberto’s definition, the U.S. big business community and its close interlocks with the state also fits the description. That makes little sense.

Roberto pays little attention to fascist movements, which are far more than just their voting base in the lower middle class. They included extra-parliamentary quasi-military formations capable of seizing power. The German ruling circles could not ignore that possibility and therefore were forced to incorporate the Nazi Party into the government.

Roberto similarly minimizes the role of mass organizations during the New Deal. Without the labor movement, without the strikes, Roosevelt’s reforms would very likely not have been enacted.

The weakness of this monochromatic view of capitalist dictatorship is most evident when Roberto calls President Trump a bona fide fascist.

Trump’s nationalism is implicitly when not explicitly racist, and Republican attempts to regulate women’s bodies and return women to traditional roles as mothers and homemakers both fit right into a fascist program. Everything else, however, is populist rhetoric that is belied every day by policies friendly to Trump’s sectors of capital out for a quick buck.

It is hardly fascism when Republican-led governments from federal to state level are busily trying to deregulate everything except the police and the military. President Trump heads a classic kleptocratic oligarchy. That is its sole economic strategy. Its mass base is among fundamentalist white Christians seeking a return to the mythical 1920s of small-town America. To consider Trumpism fascist is a diversion, as are today’s “small-fry fascisti” of the alt-right.

Fascism is a mass movement that arises at times of deep economic crisis. Its message is extreme nationalism combined with a populist anti-finance-capitalism with anti-Semitic overtones. It proposes a dynamic re-ordering that will cast aside the messiness of parliamentary government, political parties and labor unions in favor of a dictatorship.

Fascism is not simply the dictatorship of Capital. Fascism advocates a strong, regulatory state that will severely limit individual capitalists’ freedoms. It is able to come to power when the ruling elements of capital become incapable of agreeing on a coherent social policy to cope with the crisis through their parliamentary state, and dominant elements of capital agree that a fascist regime has become preferable to continuing chaos.

Since the root of fascism resides in the crisis of capitalism, to oppose fascism implies a united front of anti-capitalist forces rooted in the working class. It requires a program that poses radical alternatives to fascist demagogy and undermines fascism’s faux populist ideas. Indeed Roberto agrees that only a class-conscious working-class movement can prevent fascism.

The Coming of the American Behemoth provides us with an extensive treatment of reactionary and quasi-fascist thought in the 1920s and 1930s. The author’s very useful survey of the historical context, especially of the New Deal, is perhaps the best section of the book. The bulk of his somewhat too lengthy and frequently repetitive treatment focuses on writers who have attempted to understand fascism and its roots. However, simplistically identifying fascism with Big Business is not convincing.

Notes

- They would have been shocked if they had read Mussolini’s 1919 Manifesto, which called for nationalization of the arms industry, a progressive tax on capital, the seizure of 85% of military contract profits, the eight-hour day and a minimum wage, not to mention the overall Corporatist structure that included workers’ representatives in industry commissions.

back to text - Magill was a well-known staffer for The Daily Worker. Stevens was probably a pen-name.

back to text - Pierre Ayçoberry, The Nazi Question (Random House, 1981).

back to text - John Gerassi, “The Comintern, the Fronts, and the CPUSA,” in Michael E. Brown et al, New Studies In the Politics and Culture of U.S. Communism (Monthly Review Press, 1993) 79.

back to text - Paul M. Buhle, A Dreamer’s Paradise Lost: Louis C. Fraina/Lewis Corey…And the Decline of Radicalism in the United States (Humanities Press, 1995).

back to text - See, for example, G. William Domhoff’s description of the battle over Section 7a (which protected workers’ right to organize) in his The Power Elite and the State (Aldine de Gruyter, 1990) 80 ff). Roberto seems unaware of “power structure” research in the United States and elsewhere. See Domhoff and eleven others, Studying the Power Elite: 50 Years of Who Rules America (Routledge, 2018), which is accessible online.

back to text - Not to be confused with the Bonus Army, some 43,000 veterans and their families, who marched on Washington, D.C. in the Summer of 1932. They were suppressed by the Army.

back to text - Oppenheimer, “What Fascism is, and isn’t,” ATC #194 (May/June, 2018).

back to text - Oppenheimer, White Collar Politics (Monthly Review Press, 1985), 188.

back to text - Konrad Heiden, Der Fuehrer (Eng. trans., Houghton Mifflin, 1944), 113.

back to text - The Collapse of the Weimar Republic (Princeton U. Press, 1981), 315, 320.

back to text - Frederick L. Schuman, The Nazi Dictatorship (Alfred A. Knopf, 1935), 10.

back to text - The Spirit and Structure of German Fascism (Viking Press, 1937), 22.

back to text - M.W. Fodor, The Revolution Is On (Houghton-Mifflin, 1940), 156; Douglas Miller, You Can’t Do Business With Hitler (Brown & Co., 1941), 7.

back to text - Jane Caplan, “Theories of Fascism…” in Michael N. Dobkowski and Isidor Wallimann, Radical Perspectives On the Rise of Fascism in Germany, 1919-1945 (Monthly Review, 1989), 137. See also Heiden on the Nazis’ internal disputes up to 1934.

back to text - J. Craig Jenkins and Craig M. Eckert, “The Corporate Elite, the Conservative Policy Network, and Reaganomics”; James Salt, “Sunbelt Capital and Conservative Realignment in the 1970s and 1980s,” in Critical Sociology v. 16 no. 2-3, Summer-Fall, 1989.

back to text

September-October 2019, ATC 202