Against the Current, No. 202, September/October 2019

-

Hope Is in the Streets

— The Editors -

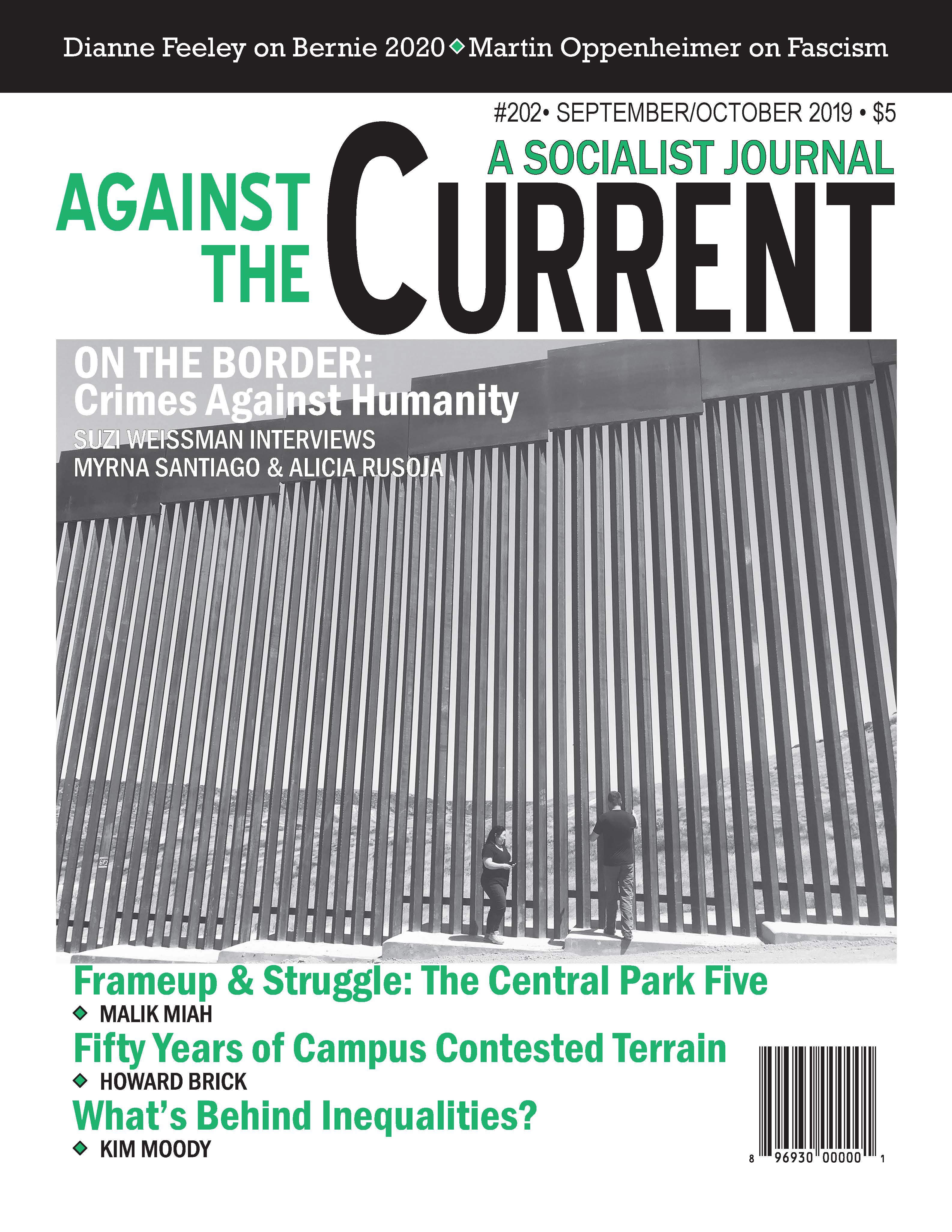

Talking to Those on the Border

— Suzi Weissman interviews Myrna Santiago & Alicia Rusoja -

What the Sanders' Campaign Opens

— Dianne Feeley -

Making the Master Race Great Again

— Steven Carr -

The Central Park Five Frameup

— Malik Miah -

Algerian Feminists Organize

— Margaux Wartelle interviews Wissem Zizi -

Palestine: Imperative for Action

— Bill V. Mullen -

The Crisis of British Politics

— Suzi Weissman interviews Daniel Finn - Siwatu Salama-Ra Conviction Overturned

-

Contested Terrains on Campus

— Howard Brick - Reviews

-

Competition, Inequality & Class Struggle

— Kim Moody -

Learning Through Struggle

— Marian Swerdlow -

What Is Working-Class Literature?

— Matthew Beeber -

A Debate That Never Ends

— Steve Downs -

Fascism--What Is It Anyway?

— Martin Oppenheimer -

Bolivia's Legacy of Resistance

— Marc Becker -

China: From Peasants to Workers

— Promise Li - In Memoriam

-

In Memoriam: James Cockcroft, 1935-2019

— Patrick M. Quinn

Suzi Weissman interviews Myrna Santiago & Alicia Rusoja

ON HER JACOBIN radio show in late July, Suzi Weissman interviewed Myrna Santiago and Alicia Rusoja, just back from the U.S.-Mexico border. Myrna Santiago is a professor teaching Latin American history and director of the Women & Gender Studies program at Saint Mary’s College of California. Her research focuses on environmental history, and specifically the oil industry in Mexico. She’s working on a history of the 1972 earthquake that destroyed Managua in Nicaragua.

Alicia Rusoja teaches immigrant rights and social justice at Saint Mary’s. Her research focuses on the intergenerational literacy teaching and learning practices for Latino/a immigrants. This is an edited version of their discussion.

Suzi Weissman: Myrna Santiago and Alicia Rusoja are just back from a week at the border where they spent time talking to the migrants themselves, men, women and children, and also deported veterans and deported mothers of Dreamers in Tijuana. They sat in at an immigration court and talked to support groups. We’re going to get their reflections. Myrna, given that you’ve been going back and forth now five different times in the last three years, can you tell us about the cruelty of the current policies?

Myrna Santiago: This White House has been implementing cruel policies, but they didn’t start with the current occupant of the White House. President Obama still holds the title for Deporter-In-Chief. But the level of fearmongering that has been coming out of this White House — and what that has meant for migrants and for people on the border — is new.

Trump has increased the level of fear that immigrants experience — they come through treacherous terrain, they face organized crime in Mexico trying to take advantage of them, and then they don’t know what will happen to them at the border or with the raids that may take place once they are in the country. It’s truly unprecedented.

Migrants are coming because they realize that their options, whether in Honduras or Guatemala or El Salvador, are so much worse that they’re willing to risk everything to get to the United States. When they get here, they meet a court system that is designed to make it not only humiliating but really impossible for them to get asylum.

SW: Maybe you could talk a little about U.S. foreign policy, and how it’s implicated in that wave of immigration?

MS: For those who were around through all the horrible wars of the 1980s, we have to remember the role that Washington played in those wars and in maintaining a level of violence in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador as part of the Cold War.

In that period, the United States promoted an idea that the Cubans were coming through Nicaragua and the Sandinista government were their puppets. The Reagan administration talked about how Cuban communists would be on the border any day now, because all you had to do is come up through Mexico —

SW: And get to Hartinger, Texas — I’ll never forget it.

MS: Absolutely, yes. What is happening today in many ways is a legacy of U.S. foreign policy in the 1980s. It is different for each of the three countries in the so-called Northern Triangle of Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras. But it is a legacy because countries that were utterly destroyed by war were left with easily available weapons of war.

In the case of El Salvador specifically, refugees had been coming to the United States for years as a result of the American government propping up a military dictatorship for 10 years. Many ended up in Los Angeles, in your backyard — and all these young kids that were coming into a hostile environment organized themselves into gangs to protect themselves in the LA neighborhoods where they lived.

When they got back to El Salvador, they found nothing for themselves. The country had been destroyed after ten years of a war that was paid for by the United States, and there were more weapons than you could ever want.

Drug organizations from Colombia to Mexico, then, found young men with good organization, willing to use these weapons to make Central America into a corridor for cocaine coming from Colombia to the United States.

And that turned the situation in El Salvador into a new kind of war — massive violence that then got exported to Honduras as the gangs got involved in Honduras, and then to Guatemala, as they also started setting up outposts there.

It didn’t get any better when Washington supported a coup in Honduras, in 2009 — in fact you got more instability. So that combination of factors created a situation: Where are people going to go to get away from the violence? One of the places they’re going to go is the United States.

SW: Alicia, after a long trip, many of these migrants arrive in Tijuana and are told they can apply for asylum in the United States. And then, in the beginning we saw them separated from their families and detained — and others are now being forced to wait in Mexico. While you and Myrna were there a week ago, you had a chance to talk to a number of migrants, and to the staff as well at these severely underfunded shelters. What challenges do they face?

AR: We visited several shelters, some sheltered women and children, some others men and children. They were overcrowded. Some staff members were even taking people into their own homes because there was nowhere to go. Migrants were living in uncertainty.

There was no clear pathway that they could follow to cross the border legally. They were living in underfunded conditions. The children were not able to go to school or receive any kind of educational support because they were in limbo.

The process for being seen by a judge was unclear. There were a lot of rumors and misinformation. The new system of “metering” contributes to this confusion.

Migrants have to put their names on a piece of paper that used to be managed by migrants themselves, but then the Mexican government began to manage it. This is an unofficial process — it’s not like you go talk to immigration and they put your name on their list. No, you put it on a piece of paper, so a lot of abuse has been happening. We heard migrants are often asked to pay between $700 and $1000 to have their names moved up because the waits are so long.

Some people we met said “my number will come up maybe in October, or March next year.” They’re waiting too long. They’re getting desperate, because, like Myrna said, they’re running for their lives.

During this period, they’re not able to work, they’re not able to go to school — and they’re willing to do anything to get their names moved up. That creates a dangerous situation with the potential for abuse.

SW: Before that, presumably they would have been held in detention centers on the U.S. side of the border, and in terrible conditions. But being forced to wait in Mexico and the corruption on the part of Mexican officials and others there, that are taking advantage of it — is this sort of like an unintended consequence of what Trump forced on Mexico?

AR: Well, I think Trump’s policy is purposeful. Trump and the U.S. government have been trying to make it so physically and emotionally impossible for people to cross that they will self-deport. Even if their court date comes, they’ll say “Fine, just send me back.” But that’s impossible if people fear for their lives. We saw this in court — people say “I cannot go back.”

There was a time when people could just come, make their case, and wait for the decision in their case to go through the courts while they were with their family members, wherever their family members were in the United States. But the whole idea of detaining people, basically putting them in prison while they wait for their cases, is a more recent practice.

And it’s absolutely terrible. We know that part of why Trump is separating family members is because it is illegal for the government to hold children more than twenty days. And so they say, okay fine, we’ll just separate them. We can put the kids in foster care, or send them off to a family they don’t know, and further traumatize them, while we can keep their parents in prison.

Private prisons are making money off this humanitarian disaster. The people who are benefitting, who are on the board of these private prisons, are some of the people who actually designed the anti-immigrant law. So it’s a pretty corrupt situation; it’s very upsetting.

SW: Are either of you surprised that Trump was able to force this on AMLO — Andres Manuel Lopez-Obrador — in Mexico, whom people heralded as an exception to the far-right populists elected elsewhere? What kind of a compromise has it been, do you know?

AR: The Lopez-Obrador government is defunding humanitarian shelters and sending the Mexican military to enforce immigration laws. When we were there, we spoke with community activists. So there were shelters and organizations that were providing services, and there were also organizations that were mobilizing and supporting the migrants in more political ways.

What we learned is that actually, the Mexican military has been hanging out on the border, in Tijuana by the border wall, and checking people’s papers. They were asking anyone for their ID, to try to find people who are not Mexican citizens.

We heard from one organization that the military was actually trying to enter the shelter, saying “we want to enter just to see the conditions.” Actually, they wanted to go in to ask for migrants’ IDs and deport them. And that’s a really dangerous thing.

SW: Is it any better on the Mexican side, waiting in shelters and being subjected to the corruption of bad actors?

MS: I suppose you would have to ask the migrants themselves. Probably the views would be all over the place. If you stay in Mexico — although most people have Mexican visas, because the Mexican government has been giving migrants visas that last 90 days while they figure out what their conditions are going to be — you’re waiting for your number to come up.

The other option is to cross the border and have the Border Patrol pick you up. Even though they will put you in detention, maybe your case will be heard earlier than if you had to wait. Those are the kinds of choices that migrants have to make, that they have been making.

There are a number of categories of people who continue to be deported and whom we shouldn’t forget.

I spoke to a woman who belongs to an organization known as the Dreamers’ Moms. She is one of many women whose children are U.S. citizens; her kids are living here, but she has been deported to Mexico. Another group is veterans. These are American servicemen who are not U.S. citizens or who undocumented.

Dreamers’ Moms is conducting workshops for children in shelters in Tijuana. They’re organizing art projects. The day that we were visiting, one mom told us about how they just held a workshop using puppets so that the kids could express themselves, to show how they’re feeling and what’s going on in their lives.

They have been developing a program to prepare children who are going to be separated from their parents when and if they cross the border. They want to be sure it will not come as a shock to the children when all of a sudden their parents go in one direction, and then they go in another.

SW: How are the immigration courts function?

AR: We had the opportunity to sit for many, many hours watching different cases. One that we observed was of a trans woman. When her case came up — like many other people that day — she did not have a lawyer. She was told by the judge, “it’s your fault you don’t have a lawyer. We gave you time to find a lawyer and so you’re going to have to represent yourself because you were irresponsible and didn’t find a lawyer.”

This woman said, “Well I tried everything, but every time I write my name down on this list” — again this issue of lists. There’s a list that someone runs within the detention center that is supposed to provide the migrants with support in filling out the paperwork and connecting them with pro bono lawyers.

But what we heard repeatedly, including in this case, is that the person writes their name down but is unable to find anyone to represent her before the judge.

Clearly this woman was having a really hard time. The judge kept saying to her, “You do not understand my questions, your answers are too long.” The judge stopped the hearing, walked away, and then came back about 10 minutes later.

While the hearing was in recess, the woman turned to others there, saying “I was just assaulted inside the detention center. My breasts are all purple. I’m completely beat up. I’ve gone twice to the hospital; I’m not being protected. All that happened was that they moved me from one place to another, but I really want to press charges against the people who have been beating me.” She also noted that she was not able to take her psychiatric medication while in detention and had not been provided with any mental health support.

When the judge came back in the woman tried to explain, “The reasons why I’m having trouble with the questions and answers is because I’m in the middle of going through a really serious crisis. I was just beat up, I need support and protection.”

The judge just shut her down. When the detainee finally was able to say, “I was assaulted, please hear me out,” the judge responded, “I have no jurisdiction over this private detention center. If you have any issues or have been hurt in any way, you need to put in a report.”

The detainee said “I did put in a report, and it still has gone unheard. I need your help.” The judge said, “Again, I have no jurisdiction. All I can do is have you fill out a form saying that you’re running away from assault, especially because you’re trans. We can hear your case about the things that happened to you back in Nicaragua. But we’re not going to hear what’s happening to you right now.”

It was horrific to see this woman in an incredible amount of physical and emotional pain and being told no, we’re not going to hear it; shut up and that’s it.

These are the kind of conditions that people are living in. They’re running for their lives, and then they’re being put in cages and being treated like animals.

SW: Myrna, I’m going to give you the last word. We’ve been listening to this byzantine, horrendous legal violence. What are your hopes for any different outcome, and what do you suggest that ordinary people should be doing to prevent this from happening?

MS: I think we need to denounce it — in every way shape or form, in every forum that is possible, in every conversation, in every classroom and workplace, any way that we can; to say that this is not acceptable.

This is not how you treat human beings who are in distress. And there are many reasons why they’re going to keep coming. Climate change is a big driver of migration, and the failure of monocrop agriculture is another.

We cannot allow this cruelty to be normalized. We have to continue the protests, writing op-ed articles or letters to the editor, writing to your congressperson, writing to the White House, continuing pressure to say that this is not normal, this is not acceptable, and that this has to stop. There’s no question about it. We have to take it all the way to the 2020 election and beyond.

September-October 2019, ATC 202