Against the Current, No. 199, March/April 2019

-

Whose "Security" -- and for What?

— The Editors -

MLK in Memphis, 1968

— Malik Miah -

California Burning, PG&E Bankrupt

— Barri Boone -

PG&E Bankruptcy

— Barri Boone -

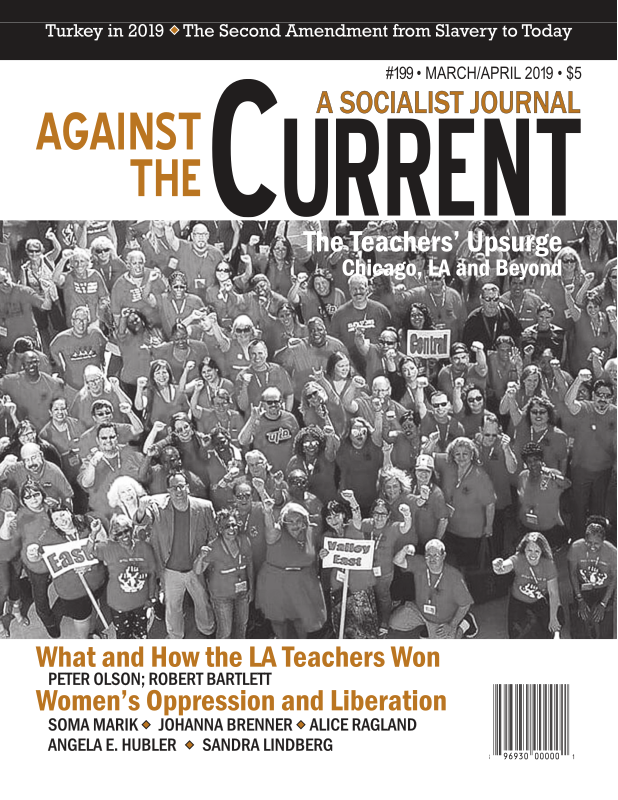

What Los Angeles Teachers Won

— Peter Olson -

The UTLA Victory in Context

— Robert Bartlett -

Chicago Charter Teachers Strike, Win

— Robert Bartlett -

Turkey in 2019: An Assessment

— Yaşar Boran -

Betraying the Kurds

— David Finkel -

The Strange Career of the Second Amendment, Part II

— Jennifer Jopp -

Who Is Responsible?

— David Finkel -

A Note of Thanks

— The Editors - Socialist Feminism Today

-

Women's Oppression and Liberation

— Soma Marik -

Marx for Today: A Socialist-Feminist Reading

— Johanna Brenner -

Angela Davis: Relevant as Ever After Thirty Years

— Alice Ragland -

The Activism of Angela Davis

— David Finkel -

White Women and White Power

— Angela E. Hubler -

Lots of Scurrying But No Revolution in Sight

— Sandra Lindberg - Reviews

-

A Call to Action

— Patrick M. Quinn -

Orbán: Strong Man, Authoritarian Ideology

— Victor Nehéz -

A Sympathetic Critical Study

— Peter Solenberger -

Further Reading on the Russian Revolution

— Peter Solenberger

Malik Miah

“Something is happening in our world. (Yeah.) The masses of people are rising up. And wherever they are assembled today, whether they are in Johannesburg, South Africa; Nairobi, Kenya; Accra, Ghana; New York City; Atlanta, Georgia; Jackson, Mississippi; or Memphis, Tennessee, the cry is always the same: ‘We want to be free.’ (Applause.)” —“I’ve been to the mountaintop,” address delivered at Bishop Charles Mason Temple, Memphis, Tennessee, by Martin Luther King, Jr., April 3, 1968)

THE ABOVE PASSAGE comes from Martin Luther King’s famous speech given the evening before his assassination on April 4. King was expressing his own mortality — and why the struggle for justice in Memphis and around the world couldn’t be stopped, whether he lived or died.

While King’s life is officially celebrated on his birthday in January — the first and only national holiday to honor an African American — it could be argued that his assassination, where and when it occurred and why King was there, shows more profoundly what King’s legacy symbolizes to Black and other working people.

King strongly supported working-class solidarity with striking workers, community organizing to support super-exploited Black workers and their families, and the central need to organize nonviolent protests and demands on the ruling powers that be to win fundamental change.

King also applied this radical democratic vision to international upsurges and antiwar struggles, like the one over the Vietnam War.

Mass Action Behind Legal Victories

King led the masses of Black people to historic victories. Mass direct action protests scared the white ruling class into changing laws in order to end legal segregation — at least on paper — the most significant being the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Those fundamental legal victories opened the door to voting across the country, especially in the Jim Crow South where white supremacists had for decades successfully invoked “states rights” to overturn the civil and voting rights won by freed slaves, even though the language in the new constitutional amendments guaranteed those rights (13th, 14th and 15th).

The Southern white establishment believed the new federal stance on segregation could be rolled back. They fought back and kept their segregation in place. To answer them required more than a legal response. King and more radical civil rights factions understood that mass action would continue to be a key tactic to pressure the federal and state governments — of both major parties — to act.

Sanitation Workers Strike

The strike of Black sanitation workers in Memphis reflected that determined vision. King’s nonviolent direct action strategy was never only about winning legal equality. His central goal was achieving full economic justice.

A longtime friend and leader of the civil rights movement, Reverend James Lawson, asked him to come to Memphis. King and his organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), agreed.

Memphis had a sizable Black population. Yet, as in all former slave states, it was a city run by whites for whites. African Americans were second-class citizens.

The city sanitation department had Black and white employees. But Black workers could not shower after work in the department’s facility. Black sanitation workers could not take shelter in rain storms and had to hide inside their own trucks.

On February 1, 1968, two workers were crushed to death. The city’s inaction led to the unauthorized strike.

As summarized in the report by “The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute” at Stanford University:

“On 1 February 1968, two Memphis garbage collectors, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were crushed to death by a malfunctioning truck. Eleven days later, frustrated by the city’s response to the latest event in a long pattern of neglect and abuse of its black employees, 1,300 black men from the Memphis Department of Public Works went on strike. Sanitation workers, led by garbage-collector-turned-union-organizer T. O. Jones, and supported by the president of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), Jerry Wurf, demanded recognition of their union, better safety standards, and a decent wage.

“The union, which had been granted a charter by AFSCME in 1964, had attempted a strike in 1966, but failed in large part because workers were unable to arouse the support of Memphis’ religious community or middle class. Conditions for black sanitation workers worsened when Henry Loeb became mayor in January 1968. Loeb refused to take dilapidated trucks out of service or pay overtime when men were forced to work late-night shifts. Sanitation workers earned wages so low that many were on welfare and hundreds relied on food stamps to feed their families.

“On 11 February, more than 700 men attended a union meeting and unanimously decided to strike.”

Soon supported by the local NAACP branch, the strike could have been resolved on February 22, when the city council voted to recognize the union and recommended a wage increase. Mayor Loeb rejected the city council vote, and after police the next day used mace and teargas against nonviolent demonstrators, 150 local ministers formed Community on the Move for Equality (COME), under James Lawson’s leadership.

“By the beginning of March,” the Stanford Institute report notes, “local high school and college students, nearly a quarter of them white, were participating alongside garbage workers in daily marches; and over 100 people, including several ministers, had been arrested.

“The strikers were supported by the local steelworkers union that allowed them to use their hall for meetings. Heavily redacted files released in 2012 showed that the FBI actively monitored the strike.”

Twelve days after King was assassinated, the strike successfully ended with a settlement that included union recognition and wage increases, although additional strikes had to be threatened to force the city to honor its agreements.

Lessons for Today

The reality then was that the white ruling class of Tennessee still opposed the rights of African Americans and did not easily end its segregation laws and practices in the public and private sectors.

It took some time for the civil rights laws to impact Memphis and the state. The first African-American mayor of Memphis was elected in 1991.

At the same time, as elsewhere after King’s assassination, his proteges mostly gave lip-service to two key planks of King’s legacy: The Poor People’s Campaign for economic justice, and his opposition to the Vietnam War as a central concern of Black people.

Most of his leading followers sought public office and economic opportunities, while the traditional civil rights groups continued the legal fight.

The left wing of the movement (Black Power advocates, Black Nationalists, Pan Africanists and socialists) turned toward more radical anti-capitalist solutions, arguing that full equality was not possible in the capitalist system. These groups were targeted by the FBI and its covert operations that had already been directed against Black leaders such as Malcolm X (assassinated in 1965) and Martin Luther King, Jr.

The debates in the 1960s between the established leaders and more militant youth were about the class issues within the Black community. Seen by the left as a moderate, King was critical of capitalism while continuing to believe that the system could be reformed.

The demands he advanced for economic justice — to win full equality through programs like school desegregation and affirmative action, and support to the economic fight of Black workers — remain just as relevant today as they were in 1968.

He understood that legal equality was only the first step toward ending 400 years of being treated as less than fully human by white people and ruling institutions. That’s also why Reverend William Barber of North Carolina is seeking to revive a new Poor People’s campaign.

In one of King’s most profound speeches linking racial issues and war was delivered exactly a year before his murder. He linked the War on Poverty with the U.S. war on the Vietnamese people. His own comrades in the SCLC and other civil rights groups, white liberals, and the editors of The New York Times criticized him for doing so.

That speech, and his leadership, are still fitting as the U.S. government continues to occupy military bases in dozens of countries, bombs numerous Middle Eastern countries and pushes for new wars in Latin America:

“It seemed as if there was a real promise of hope for the poor — both black and white — through the poverty program. There were experiments, hopes, new beginnings. Then came the buildup in Vietnam and I watched the program broken and eviscerated as if it were some idle political plaything of a society gone mad on war, and I knew that America would never invest the necessary funds or energies in rehabilitation of its poor so long as adventures like Vietnam continued to draw men and skills and money like some demonic destructive suction tube. So I was increasingly compelled to see the war as an enemy of the poor and to attack it as such.” —“Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence, ”delivered at Riverside Church in New York City, April 4, 1967

March-April 2019, ATC 199