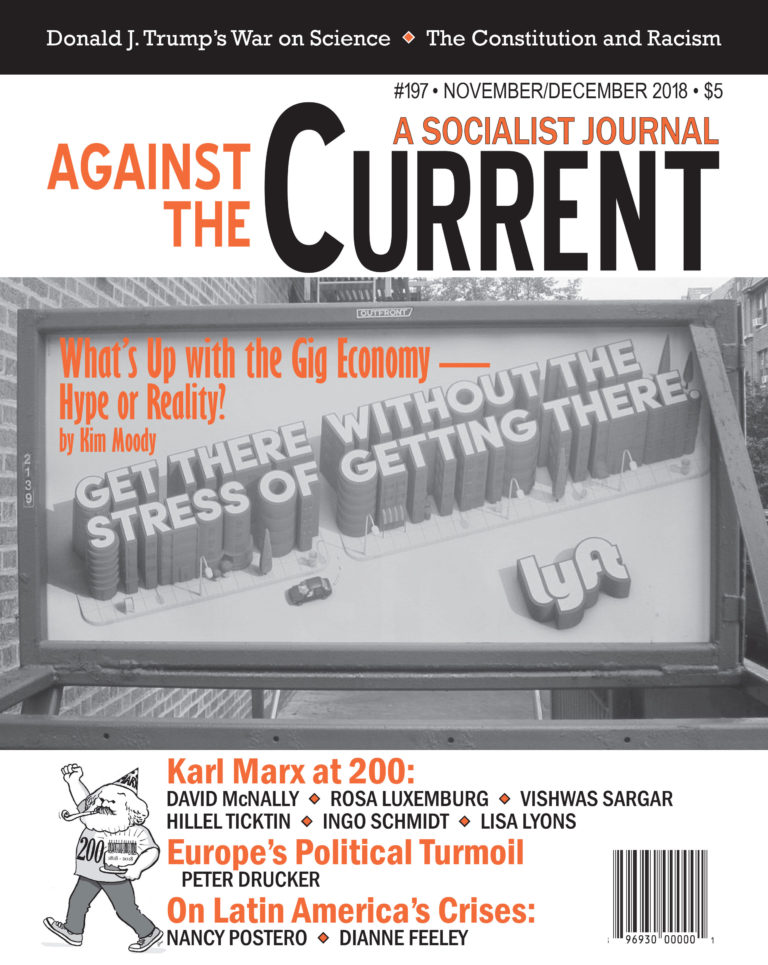

Against the Current, No. 197, November/December 2018

-

Supreme Toxicity -- Confirmed

— The Editors -

The Constitutional Root of Racism

— Malik Miah -

Trump and Science

— Ansar Fayyazuddin -

Europe's Political Turmoil (Part I)

— Peter Drucker -

Ecosocialism or Climate Death

— Ecology Commision of the Fourth International - Realities of Labor

-

Is There a Gig Economy?

— Kim Moody - Karl Marx at 200

-

Karl Marx: Revolutionary Heretic

— David McNally -

Marxist Theory and the Proletariat

— Rosa Luxemburg -

Marx and the "International"

— Vishwas Satgar -

Karl Marx in the 21st Century

— Hillel Ticktin -

Marx's Capital as Organizing Tool

— Ingo Schmidt - A Century Ago

-

The End of "The Great War"

— Allen Ruff -

Triumph and Tragedy

— William Smaldone - Reviews

-

The Making of Corporate Empire

— Jane Slaughter -

The Saga of a City Rising

— Michael J. Friedman -

Slavery and Capitalism

— Dick J. Reavis -

The Logic of Human Survival

— Barry Sheppard -

Architects of Mass Slaughter

— Malik Miah -

Two Powerful Films on Indonesian Mass Terror

— Malik Miah -

The Wars of Rich Resources

— Nancy Postero -

Latin America Crises and Contradictions

— Dianne Feeley - In Memoriam

-

Jan and Carrol Cox, Political Activists

— Corey Mattison

Malik Miah

The Army and the Indonesian Genocide:

Mechanics of Mass Murder

By Jess Melvin

Routledge, 2018, 319 pages, $65 hardcover, $39 Kindle.

The Killing Season:

A History of the Indonesian Massacres, 1965–66

By Geoffrey B. Robinson

Princeton University Press, 2018, 429 pages, $35 hardcover.

JESS MELVIN ACQUIRED a massive trove of Indonesian army secret files in 2010 in Aceh, took them home to Australia, and they became the basis of her book. The Army and the Indonesian Genocide is one of two important new books on Indonesia and the U.S.-backed army coup and massacres of up to one million members, supporters and allies of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) in 1965-66.

Melvin’s book along with Robinson’s The Killing Season are must reading. New research documents how the mass slaughter carried out by the army, and exposes the official big lies of why the PKI and the Left were destroyed. The terror was also systematically directed at ethnic Chinese and non-Muslims. The PKI, banned in 1966, remains illegal and denounced to this day.

Under the blows of the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the army chief and “Red Slaughterer” Suharto resigned as president in May 1998. He died in January 2008, never having been brought to justice. The Reform period (Reformasi) after the fall of the dictator opened the door to discussing the historical record as well as the rampant corruption of his “New Order” regime.

However, the “Indonesia’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission as a Mechanism for Dealing with Gross Violations of Human Rights,” set up in 2004, was sidelined by each newly elected president.

Under domestic and international pressure, in April 2016 a symposium was held in Jakarta even though the government said no criminal reckoning was on its agenda.

The military and its supporters meanwhile continue to spread their false story about why 1965-66 happened, and to defend decrees that criminalize victims of their terror.

Official Army Propaganda

From September 30 to October 1, 1965 the top brass of the Indonesian army was wiped out by lower-ranking officers. Among the surviving top commanders were General Suharto and General Nasution, who was wounded.

In radio broadcasts, a group called the September 30 Movement (G30S) took responsibility, declaring that it had acted to prevent a rightwing military coup against President Sukarno, the country’s first president beginning in 1945.

The “alleged coup” (Geoffrey Robinson’s words) was quickly defeated by troops under the command of Generals Suharto and Nasution. In the following months, the PKI and its allied mass organizations (estimated at 3.5 million members, 20 million supporters) were destroyed. Prominent leaders were sentenced to death. Others, like PKI-chair D.N. Aidit, had already been “killed while trying to escape.”

The country was “saved” from communism. The U.S. government praised Suharto and provided financial assistance and military cooperation. This army story has been told for 50 years. Victims still alive look over their shoulders and have never received reparations from the state.

Jess Melvin, an Australian scholar and Postdoctoral Fellow in Genocidal Studies at Yale University, provides the smoking gun in what she calls “Indonesia’s Genocide Files.” She acquired a yearly report proving that the central army leadership planned and orchestrated the massacres.

They organized the regional commands, paramilitary groups, death squads, and civilians to actively participate (see “Evidence of Intent” and “Military preparations to seize state power in Sumatra,” pages 40 and 71). It was not the people “spontaneously” running “amok.”

Melvin summarizes her main argument:

“Throughout the 3,000 pages of top secret documents that comprise the Indonesian genocide files, the military describes the killings as an ‘Annihilation Operation’ (Operasi Pemunpasan), which it launched with the stated intention to ‘annihilate down to the roots” its major political rival, the Indonesian Communist Party.’

“The armed forces … ordered civilians to participate in the campaign from 4 October and established a ‘War Room’ on 11 October with the total intention to ‘carry out nonconventional warfare … [to] succeed in annihilating [the ministry’s target group] together with the people.’ The killings, it can now be proven, were implemented as deliberate state policy.” (Introduction, 1)

Her detailed research proves that General Suharto was central in planning the massacres: “He too was much more active in consolidating his position and operating independently of Sukarno. New documentary evidence indicates that Suharto sent telegrams to regional military commanders on the morning of 1 October in his assumed position of Armed Forces commander, declaring that a coup — led by the 30 September Movement — had occurred in the capital. This order was then followed by an instruction sent from Sumatra’s Mandala I commander, Mokoginta, who declared that military commanders should ‘await further orders.’”

U.S. complicity is documented. Names of targets for killing came from the U.S. ambassador’s office and CIA. Australia and the British also openly supported the army and establishment of the “New Order” rightist regime.

Melvin also discusses why genocide is a correct term for the massacres. Genocidal definitions (based legally on the Geneva Conventions after WWII) are interesting but not key to understanding what happened in Indonesia. Whether one calls it politically based genocide or ethnic cleansing as occurred in many other countries, it was without doubt a planned pogrom.

Pretext for Massacres

In The Killing Season, Geoffrey Robinson, a former Amnesty International researcher (for six years) and Professor of History at the University of California Los Angeles, also shows through his research, interviews and analysis how the murderous campaign was deliberately organized by the army — before and after the banning of the PKI. He shows the role of the United States and other imperialist powers.

The explosion of violence was premeditated and ideologically driven, as Max Lane, an Australian Indonesia expert and socialist, wrote in his review of Melvin’s book:

“The mass killings proceeded through four organized stages: an initiation phase, a public violence phase, a phase of systematic mass killings, and a final consolidation phase, which also included purges. The bloodshed erupted following a botched conspiracy by elements in the PKI, who were seeking to replace the Army High Command with friendlier figures. It was badly organized, premature — and carried out unbeknownst to their comrades and mass supporters. The military used it as a pretext to launch a devastating counter-attack.”

PKI and Army in Conflict

Robinson amplifies on several key points — the Army and its doctrine of “dual function,” the role of culture lying behind supposedly “spontaneous” civilian attacks on the left, struggles between Nationalists, Communists and the military, and the role of foreign intervention. (19-26)

He elaborates in Chapter 3, “The Pretext,” on how the army orchestrated the events in 1965, the removal of Sukarno as president and the terror campaign and slaughter that ensued. Suharto had total support from Washington.

Robinson reviews the evolution of the PKI from a failed uprising in 1925 against the Dutch colonial rulers, to the rise of the Indonesian nationalist army under the Japanese occupation (1942-45) and the 1948 Maduin rebellion in West Java.

As he explains, the PKI built a new leadership and changed its strategy — with no reference to armed struggle — to full support of president Sukarno’s left nationalism. This led to the party’s massive growth, with over 20 million members and supporters in a country then of 100 million.

The army high command saw this growth as a threat to its economic and political influence. It despised the PKI and sought to undermine it years prior to 1965. It also did not support a big role for Muslims in politics.

The freedom struggle from Japanese occupation (1942-45), the declaration of Independence from Dutch rule in 1945 and a four-year war until victory in 1949, was led by the secular nationalist Sukarno (“father of the country”) and creator of its political concept as the basis of independent Indonesia (Nasakom — Nationalism, Religion, Communism).

Ideologically Sukarno developed what he called “Guided Democracy” (1957). But the three factions were in a permanent battle to win more influence inside the country and sought support from the powerful president. There was only one election in 1955, which did not settle this battle.

As Sukarno moved closer to the PKI in the early 1960s, it was inevitable the army command structure would fight back. The events of 1965 were the brutal continuation of a longstanding conflict.

U.S. Support to Regime Change

Robinson explains the growing strength of the PKI in the 1950s. But Sukarno kept the communists away from high government positions. The army, on the other hand, was more than an apolitical force for defense.

Since the war of liberation against Dutch colonialism, the army had become a powerful factor in Indonesian politics. Its influence grew further after it took control of Dutch enterprises that were seized during protests in 1956–58.

Its “dual role” (Dwifungsi), as an economic power house and armed defender of the state, put the military high command in a special position within the state.

The PKI and even Sukarno underestimated the army’s power. The U.S. State Department did not. Robinson describes how Washington changed its approach to trying to win support among the army command stricture through providing training and military aid.

The top command, a privileged social layer allied with landlords, businessmen and conservative religious leaders, was seen as the most reliable anticommunist force in the country. For the United States, this new strategy (after supporting regional rebellions against Sukarno that the army put down) would prove a success some years later.

Robinson shows how Western governments drew up contingency plans to prevent the PKI from translating its growing social weight into political power. The Killing Season includes a photo of an infamous British Foreign Office memo of December 1964 that read “A premature PKI coup may be the most helpful solution for the West — provided the coup fails.”

A few months later, a very similar scenario took place with the putsch of the G30S.

Abortive Putsch, Falsified History

The plan was to abduct generals who were known to be right wing and force them to resign. For this, the G30S counted on support from Sukarno: the movement would abduct the generals, and in the name of the Indonesian nation demand that they be sacked. Sukarno would then use this opportunity to get rid of some of his most powerful rivals by acceding to the demand of the movement.

For unknown reasons, the G30S ended up not abducting the suspected generals, but killing them. Contrary to army propaganda, the PKI as such was not involved in the group — not even its central committee was informed by Aidit.

This explanation, Robinson explains, has the benefit of explaining the incompetent nature of the movement. It answers the question of why, if there had been a plan to seize power, the PKI failed to mobilize its millions-strong base in support of the G30S.

Robinson concludes, then, that “the mass killings of 1965–66 were set in motion by the army itself … It was the army leadership, under Major General Suharto, that introduced the idea that the political crisis of October should and could be resolved through violence and provided the means through which that intention was achieved.” (”The Army’s Role,” Chapter 6, 148-176)

This falsification of history was facilitated by Western officials and journalists (The New York Times and Time magazine) who repeated the army line. The violence following the G30S was a not a two-sided civil war — it was a one-sided, bloody, class war.

Neither Robinson nor Melvin explicitly charge the United States, UK, Australia or others behind the coup by Suharto although these imperialist powers hailed the change of government. What both books provide in detail makes that obvious.

Western powers did much to stabilize the new Suharto “New Order” regime by giving it support and economic aid that had been withheld from Sukarno. Melvin says evidence proves that Western intelligence backed the massacres.

In The Atlantic (Oct. 20, 2017) using documents released by the National Security Archive, Vincent Bevins explains:

“Some elements within the U.S. government had been trying to undermine or overthrow Sukarno, Indonesia’s anti-colonial independence leader and first president, far before 1965. In 1958, the CIA backed armed regional rebellions against the central government, only calling off operations after American pilot Allen Pope was captured while conducting bombing operations that killed Indonesian soldiers and civilians. Agents reportedly went so far as to stage and produce a pornographic film starring a man wearing a Sukarno mask, which they hoped to employ to discredit him. It was never used. Then for years, the United States trained and strengthened the Indonesian army. After John F. Kennedy›s death derailed a planned presidential visit to Jakarta and relations worsened with the Johnson administration, Sukarno strengthened alliances with communist countries and employed anti-American rhetoric in 1964.

“In 1965, when General Suharto blamed the military purge on a PKI coup plot, the CIA supplied communications equipment to help him spread his false reports before moving into power and overseeing the industrial-scale slaughter, as previously released government documents showed. Several of the documents released this week indicate that the U.S. embassy had reliable information that placed blame on rank-and-file PKI members — information that was entirely inaccurate, but nevertheless had encouraged the army to exploit this narrative.”

Sukarno was unable to stop the annihilation of his allies. Political power increasingly shifted to the military. Pressured by the army, on March 11, 1966, Sukarno effectively transferred power to General Suharto, who then ruled the country for the following three decades.

Tragic Aftermath

Even after Suharto resigned his office in 1998, the Clinton administration made sure its ties with the army were strengthened. It rejected pushing for an accounting for the decades of crimes by Suharto’s regime against his own people. (“Clinton Administration saw army’s role as key,” from National Security Archive, July 24, 2018)

The U.S. government misread the significance of its victory in Indonesia, as it stepped up its invasion of Vietnam in 1965.

Ten years later, the Vietnamese defeated the United States and its puppet regime in Saigon. That victory encouraged revolutionary nationalists and democratic socialists around the world. In 1979, three revolutions won in the Caribbean island of Grenada, Central American country of Nicaragua and the most populated country in the Middle East, Iran.

For Indonesia, the 1965 tragedy set back the struggle for five decades. Only after 1998 has new political activism emerged. These forces continue to push for truth and a reckoning of the past.

Was it Inevitable?

The class and social conflicts were inevitable. They had been going on since Japanese occupation and independence. What wasn’t known or inevitable was the success of the army’s annihilation campaign.

The PKI’s millions of members and supporters were never mobilized to act. The PKI in its support of the anti-Malaysia campaign that began in 1963 had called for a People’s armed community force. Sukarno backed it. The army didn’t, but used it to create its own paramilitary civilian force.

The PKI strategy of People’s United Front did not change. The armed people’s force was intended to strengthen the party’s and Sukarno hand, not to prepare for a revolutionary war against the army. The PKI leadership, including the party’s Chairman Aidit and secret Special Bureau, always believed that the working class and peasantry were not ready for power.

The PKI supported the popular nationalism of Sukarno, and thought he could protect them. The army backed the unity of the state, but not Sukarno’s vison that nationalism, communism and religion were the primary legs of the state. The army had openly advanced a strong anticommunist agenda.

That’s why it used charges of atheism to whip up religious hostility against the PKI after 1965, as well as against ethnic Chinese who were mostly Christians if religious. The Chinese community suffered vicious attacks. The regime said they had divided allegiances because of their Chinese heritage. (The PKI had sided with China in the Sino-Soviet dispute.)

In the end the PKI was not prepared for a confrontation. PKI leaders were caught off guard and liquidated. To this day, families of those slaughtered are still fearful about speaking about their murdered relatives.

The horror stories about the supposed crimes of the PKI (mutilations of the Generals, rapes of Muslim women) and the taboo on leftist ideas persist, continuously reinforced by the Indonesian ruling class and its thugs who attack gatherings of survivors and human rights activists.

Robinson ends his book with the conclusion that it is unlikely that we will see justice. The last survivors of the 1965–66 massacres are dying without having seen the guilty parties being judged, let alone punished.

These two books stand on earlier works and are important to understand not only the terror of anticommunism and authoritative forces, but also the complicity of U.S. imperialism.

For Indonesia to rebuild a truly democratic state, the truth of 50 years must be faced and learned to rebuild the left and a revolutionary democratic socialist movement.

November-December 2018, ATC 197